Acute pancreatitis, characterised by pancreatic inflammation, usually stems from well-documented causes like gallstone disease, excessive alcohol consumption, and trauma. However, in rare cases, it can be the initial manifestation of a pheochromocytoma, an adrenal tumour releasing excessive catecholamines. This unexpected link can puzzle clinicians due to the absence of typical pheochromocytoma symptoms. Recognising this interplay and understanding the complex pathophysiological mechanisms is challenging. Pheochromocytomas often mimic other conditions, but there are few reports of pheochromocytoma-induced pancreatitis in the medical literature.1 The absence of usual pheochromocytoma symptoms, such as sustained hypertension, complicates timely diagnosis when presenting as acute pancreatitis. This case report highlights a unique scenario where acute pancreatitis was the first sign of an underlying pheochromocytoma, underlining the importance of early identification and accurate diagnosis in managing this uncommon but potentially life-threatening association.

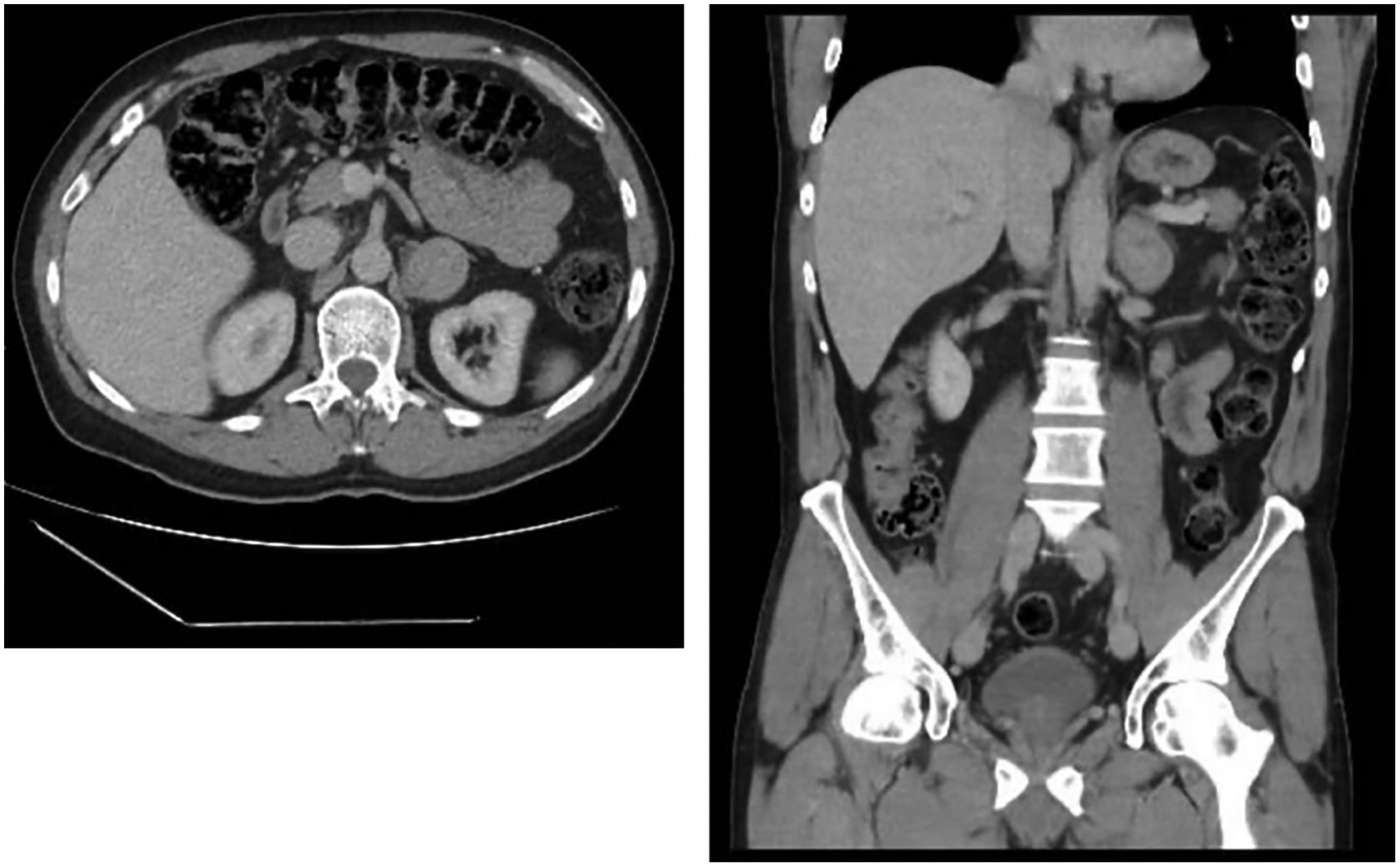

Case reportThis was a 51-year-old male referred to the Endocrinology Department after the incidental discovery of a left adrenal mass on a CT scan performed for acute pancreatitis. His previous medical history included a history of hypomania, renal microlithiasis and cholecystectomy. He was not on any regular medication. He had been admitted two days prior to the Endocrinology consultation due to acute pancreatitis, diagnosed by typical abdominal pain with amylase and lipase levels three times above the upper limit of normal (amylase 1184IU/l, lipase 936IU/l), with a CT scan revealing a 38-mm lesion in his left adrenal gland (Fig. 1). Once in hospital, potential triggers such us gallstones, alcohol intake, other toxins or drugs, hyperlipidaemia and hypercalcaemia were ruled out. Additionally, the patient had no history of recent surgery, ERCP, trauma, anatomical abnormalities in the pancreas or gastrointestinal tract or infectious symptoms.

During the initial examination, he reported colicky abdominal pain for weeks, as well as palpitations occurring once or twice a month. A pre-admission episode of elevated blood pressure and glucose levels was noted. However, 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) did not show sustained hypertension. He had no associated headache or diaphoresis.

Analysis carried out after the acute episode of pancreatitis revealed plasma metanephrines of 582mg/dl (normal <90) and 24-h urine metanephrines of 1820μg/24h (normal <341). Plasma cortisol, aldosterone and renin were within normal limits. Electrocardiogram and transthoracic echocardiography ruled out the presence of heart disease.

Given the probable diagnosis of pheochromocytoma, the patient was started on medical treatment, the alpha-blocker doxazosin 1mg per day, with a progressive increase to 2mg per day, for the two weeks prior to surgery. During follow-up, the patient responded well to doxazosin treatment, maintaining blood pressure at 115–125mmHg systolic and 80–85mmHg diastolic, with heart rate in the range of 65–75 beats per minute. Notably, beta-blockers were not added due to the patient's tendency to hypotension with low doses of doxazosin and to maintain heart rate within the target control range. Finally, a laparoscopic total left adrenalectomy was performed with no postoperative complications.

Pathology examination confirmed a pheochromocytoma. There was no infiltration of capsular venous spaces and no infiltration of the capsule. The Ki67 staining index was 5%. Post-surgery, the patient's abdominal pain resolved and his urine metanephrine levels returned to normal, with no recurrence of hypertension or hyperglycaemia.

DiscussionAcute pancreatitis as a form of presentation of pheochromocytoma, although uncommon, has been described in several previous cases in the literature.2–5 In these cases, the main challenge is to recognise the relationship between two apparently unrelated diseases in order to avoid misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis. These cases often have common features. Patients usually present with the clinical features of acute pancreatitis, such as severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and elevated pancreatic enzymes. A thorough evaluation, including imaging studies, is then performed to determine the aetiology of the pancreatitis, leading to the incidental discovery of a pheochromocytoma.

The precise pathophysiological mechanisms underlying pheochromocytoma-induced pancreatitis are not fully understood, but have been the subject of debate. It is known that pheochromocytomas release excess catecholamines, in particular epinephrine and norepinephrine, which can cause a range of cardiovascular and systemic effects. One proposed mechanism is the vasoconstrictive action of catecholamines on the splanchnic arteries, reducing blood flow to the pancreas.3 This can lead to pancreatic ischaemia, cell injury and ultimately acute pancreatitis. In addition, catecholamines can stimulate the release of inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines and chemokines, which can further aggravate pancreatic injury. This combination of processes results in a vasoconstriction/inflammation syndrome, which is the most recognised pathophysiological explanation in the literature.4

Another plausible explanation revolves around a mechanical cause, specifically a dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi.3,6 In this hypothesis, the adrenergic action of catecholamines triggers the contraction of the sphincter of Oddi, leading to increased resistance in both the biliary and pancreatic ducts. This can result in elevated intrapancreatic pressure, causing biliary reflux into the pancreatic duct and, ultimately, pancreatitis. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction can disrupt the normal flow of pancreatic juices and bile, contributing to tissue damage and inflammation. These diverse mechanisms highlight the complexity of this presentation.

In fact, cases of pheochromocytoma associated with hyperamylasaemia have been described without evidence of pancreatic involvement.2,7,8 In general, it is thought that the origin of hyperamylasaemia in these cases may be pulmonary. Ischaemic damage to amylase-containing tissues can lead to release of the enzyme. Amylase is present in both diseased lung tissue and normal tissue. Thus, when pulmonary endothelial cells are subjected to hypoxia due to the potent vasoconstrictor action of circulating catecholamines, amylase levels may increase in the absence of pancreatitis or salivary disease. In the cases described, most patients had associated cardiomyopathy and acute pulmonary oedema, explaining the pulmonary hypoxia.8,9 Therefore, in a patient with pheochromocytoma and hyperamylasaemia, not only acute pancreatitis should be considered as a differential diagnosis. This suggests the need to perform amylase isoenzyme analysis to differentiate its origin, and to add the determination of serum lipase to guide the diagnosis.10

In conclusion, acute pancreatitis as a presentation of pheochromocytoma is an uncommon but important phenomenon to consider in clinical practice. Patients with acute pancreatitis of unclear aetiology should undergo a thorough evaluation, including imaging studies, to detect the presence of a pheochromocytoma. Pathophysiological mechanisms underlying this unusual presentation include catecholamine-induced vasoconstriction and possible sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. In addition, cases of hyperamylasaemia have been documented in patients with pheochromocytoma, underscoring the importance of differentiating the origin of the amylase for accurate diagnosis. Early diagnosis and treatment can lead to successful recovery and avoid serious complications in these cases.

Patient consentWritten consent was obtained from the patient after full explanation of the purpose and nature of all procedures used.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.