Hypoglycemia is the major limiting factor in the glycemic management of type 1 diabetes. Severe hypoglycemia puts patients at risk of injury and death. Recurrent hypoglycemia leads to impaired awareness of hypoglycemia and this increases the risk of severe hypoglycemia. Recent studies have reported rates for severe hypoglycemia of 35% in type 1 diabetic patients.

ObjectivesTo assess the prevalence of severe hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes mellitus patients and to evaluate the relationship between this and impaired awareness of hypoglycemia according to the Clarke test.

Patients and methodsThe following data were collected from a cohort of type 1 diabetic patients: age, gender, duration of type 1 diabetes, treatment (multiple daily insulin injection or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion), glycemia self-control, HbA1c, episodes of severe hypoglycemia and impaired awareness of hypoglycemia.

ResultsOf the participants, 39.8% had had at least one episode of severe hypoglycemia (in the previous 6 months), 11.4% with loss of consciousness (in the previous 12 months). According to the Clark test, 40.9% had impaired awareness of hypoglycemia. Older age and longer duration of diabetes were associated with a higher prevalence of severe hypoglycemia with unconsciousness; older age and a lower level of HbA1c were associated with impaired awareness of hypoglycemia.

ConclusionsOur study allows us to confirm the high rate of severe hypoglycemia and impaired awareness of hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes.

La hipoglucemia es el principal factor limitante para alcanzar los objetivos de control glucémico en pacientes con diabetes tipo 1. La hipoglucemia grave conlleva riesgo de daño, e incluso de muerte. Tener hipoglucemias repetidas se relaciona con la aparición de hipoglucemias inadvertidas, las cuales incrementan el riesgo de hipoglucemias graves. Algunos metaanálisis recientes estiman una prevalencia del 35% de hipoglucemia grave en pacientes con diabetes tipo 1.

ObjetivoConocer la prevalencia de hipoglucemia grave en una cohorte de pacientes con diabetes tipo 1 y evaluar la dependencia entre las variables hipoglucemia grave e inadvertida evaluada mediante el test de Clarke.

Pacientes y métodosSe ha estudiado una cohorte de pacientes con diabetes tipo 1 para analizar la edad, sexo, tiempo de evolución de diabetes, tratamiento (múltiples dosis o infusión subcutánea continua de insulina), autocontrol glucémico, HbA1c, episodios de hipoglucemia grave sin pérdida de conciencia, episodios de hipoglucemia grave con pérdida de conciencia e hipoglucemias inadvertidas.

ResultadosEl 39,8% de los pacientes presentaron hipoglucemias graves sin pérdida de conciencia (últimos 6 meses) y el 11,4%, con pérdida de conciencia (últimos 12 meses). El 40,9% presentaban hipoglucemias inadvertidas y se descartó la independencia entre estas y las hipoglucemias graves. La presencia de hipoglucemias graves con pérdida de conciencia se asoció a mayor edad y mayor tiempo de evolución; las hipoglucemias inadvertidas, con una mayor edad y una menor HbA1c.

ConclusiónSe confirma el elevado porcentaje de pacientes con diabetes tipo 1 afectos de hipoglucemia grave e inadvertida.

Hypoglycemia can prove harmful to diabetic patients, and may even lead to death, thereby representing a major cause of disease-associated morbidity and mortality.1 In addition, hypoglycemia is the main limiting factor to achieving the glycemic control objectives in diabetic individuals, particularly in patients with type 1 diabetes.2

Unrecognized hypoglycemia occurs particularly in diabetic patients with a history of previous hypoglycemia and also in patients with long-standing diabetes mellitus who present autonomic dysfunction as a complication associated with the disease.1

Severe hypoglycemia is hypoglycemia requiring the help of another person to achieve recovery through the administration of carbohydrates, glucagon or other measures. Even if no confirmatory blood glucose measurement is available at the time of the episode, neurological recovery attributable to the restoration of normal glucose concentration is considered to be sufficient evidence.2

Iatrogenic hypoglycemia occurs more often in diabetic individuals who have more severe endogenous insulin deficiency, i.e., patients with type 1 diabetes and long-standing type 2 diabetes.3,4

Between 4 and 10% of all deaths of patients with type 1 diabetes have been related to the presence of hypoglycemia.5–8 Severe hypoglycemia has also been related to the presence of ventricular arrhythmias.9 Likewise, hypoglycemia often has other clinical implications, such as autonomic response failure, a negative impact upon patient quality of life, and limitations to achieving adequate glycemic control.10

In addition to the clinical effects, severe hypoglycemic episodes have a strong direct (emergency care, hospital admission, supply requirements) and indirect (work absenteeism and decreased productivity)11 economic impact.

Patients with diabetes mellitus who experience recurrent hypoglycemia are characterized by a lowered glucose threshold at which the counter-regulatory response is triggered.12 In some patients, the level triggering the counter-regulatory response is even below the level of glucose associated with neuroglycopenic symptoms. The first sign of hypoglycemia in these individuals is therefore confusion, a lowered level of consciousness, etc. As a result, these patients usually become dependent on other people to recognize and treat hypoglycemia. The development of autonomic response failure associated with hypoglycemia implies a 25-fold greater risk of severe hypoglycemia following intensive therapy.13,14

Both the hypoglycemic episode in itself and the fear of a new episode have been shown to exert a significant impact upon the quality of life of patients with diabetes mellitus.15

If autonomic failure associated with hypoglycemia has already been detected, patient education regarding the symptoms of hypoglycemia may help to revert the condition.16

The Clarke test is a tool that has been translated and validated in Spanish, and is used to assess the presence of unrecognized hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes mellitus.17,18 The test comprises 8 questions related to hypoglycemia exposure, and a subjective estimate is made of the glycemic threshold for the generation of hypoglycemic symptoms.

At this point, it would be very helpful in clinical practice to know to some degree of accuracy how many type 1 diabetic individuals suffer severe and unrecognized hypoglycemic episodes, with a view to adequately planning the necessary therapeutic measures.

The present study was carried out with two objectives: (a) to determine the prevalence of severe hypoglycemia in a cohort of patients with type 1 diabetes; and (b) to explore the dependence between severe hypoglycemia and unrecognized hypoglycemia detected by means of the Clarke test.

Patients and methodsA single-center, cross-sectional observational study was carried out following approval by the local Clinical Research Ethics Committee to determine the prevalence of patients with severe hypoglycemia without loss of consciousness in the previous 6 months or with loss of consciousness in the previous 12 months.

Calculation of sample sizeFor an expected prevalence of severe hypoglycemia with or without loss of consciousness of 35%, with a 95% confidence level (95%CI) and a precision equal to 10 percentage points, the inclusion of 81 participants was considered necessary. The prevalence data were drawn from the study published by Pedersen-Bjergaard in 2017.19

Inclusion criteriaThe study comprised patients diagnosed with type 1 diabetes who consecutively reported to the clinic and were aged 18 years or older at the time of the study, with at least one year of disease, and who were receiving insulin in a full treatment regimen (multiple dose insulin [MDI] or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion [CSII]).

Exclusion criteriaThe exclusion criteria comprised physical or mental inability to perform self-monitoring of capillary or interstitial blood glucose, current pregnancy, or language problems.

Study variablesThe study variables comprised current age; time since onset of the disease; gender; current treatment (MDI or CSII); self-monitoring of blood glucose (capillary or interstitial without alarms or continuous interstitial with alarms); weighted glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) corresponding to the previous 12 months, calculated as: [(HbA1c1×months)+(HbA1c2×months)+(HbA1cX×months)]/months; severe hypoglycemia without loss of consciousness in the previous 6 months (yes or no); severe hypoglycemia with loss of consciousness in the previous 12 months (yes or no); unrecognized hypoglycemia detected by means of the Clarke test. All the questionnaires were evaluated through the website of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition (Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición), with a score of ≥4 being considered positive. A doubtful result was defined as the absence of unrecognized hypoglycemia.20

The presence of severe hypoglycemia was assessed by two specific questions of the Clarke test: how often have you experienced severe hypoglycemic episodes WITHOUT loss of consciousness in the last 6 months? (i.e., episodes in which you have felt confused, disoriented, or tired and unable to treat the situation of hypoglycemia yourself). How often have you experienced severe hypoglycemic episodes WITH loss of consciousness in the last 12 months? (i.e., episodes accompanied by loss of consciousness or seizures requiring the administration of glucagon or intravenous glucose).

The data were collected during the routine medical interview, after the patient had signed the informed consent.

Statistical analysisThe GRANMO sample size calculator, version 7.12, April 2012 (free software) was used to estimate the number of patients needed for the study. The G-Stat 2.0 package (free software) was used for the statistical analysis of the data. Qualitative variables were reported as percentages, while quantitative variables were reported as the mean and standard deviation (SD). The prevalence of severe hypoglycemia with and without loss of consciousness and unrecognized hypoglycemia was expressed with the corresponding 95% confidence interval. The proportions Z-test was applied from the expected value of 35% for the null hypothesis, estimated from the study of Pedersen-Bjergaard.19 The dependence between severe and unrecognized hypoglycemia was evaluated using the χ2 test. The Student t-test was used to compare the means between two independent groups, following assessment of the equality of variances (the Fisher Snedecor test). Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05.

ResultsThe study comprised data from 88 consecutive patients meeting all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria.

The mean patient age was 40.7 years (SD: 13.4), and the duration of the disease was 18.6 years (SD: 10.5). A total of 57.9% of the patients (n=51) were male and 42.1% (n=37) were female. In turn, 72.7% (n=64) were treated with multiple dose insulin (MDI) and 27.3% (n=24) were treated with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII). In total, 79.6% (n=70) used capillary blood glucose controls, 4.6% (n=4) non-alarm flash glucose monitoring, and 15.9% (n=14) continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) with alarm (an integrated CSII+CGM system with suspension in predicting hypoglycemia). The mean HbA1c concentration was 7.5% (SD: 0.9) for the global patients.

A total of 39.8% (95%CI: 29.5–50.1) of the patients had experienced some severe hypoglycemic episode without loss of consciousness in the previous 6 months, with no statistically significant differences versus the expected value of 35% (p=0.35). A total of 11.4% (95%CI: 5.6–19.9) of the patients had experienced some severe hypoglycemic episode with loss of consciousness in the previous 12 months. In turn, 40.9% (95%CI: 30.6–51.9) of the patients had unrecognized hypoglycemia according to the Clarke test.

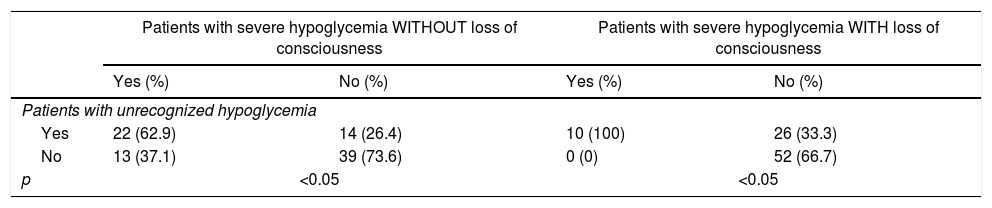

The data ruled out independence (p<0.05) between unrecognized hypoglycemia and severe hypoglycemia with loss of consciousness, and between unrecognized hypoglycemia and severe hypoglycemia without loss of consciousness (Table 1), based on the χ2 test.

Relationship between unrecognized hypoglycemia and severe hypoglycemia with and without loss of consciousness.

| Patients with severe hypoglycemia WITHOUT loss of consciousness | Patients with severe hypoglycemia WITH loss of consciousness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | |

| Patients with unrecognized hypoglycemia | ||||

| Yes | 22 (62.9) | 14 (26.4) | 10 (100) | 26 (33.3) |

| No | 13 (37.1) | 39 (73.6) | 0 (0) | 52 (66.7) |

| p | <0.05 | <0.05 | ||

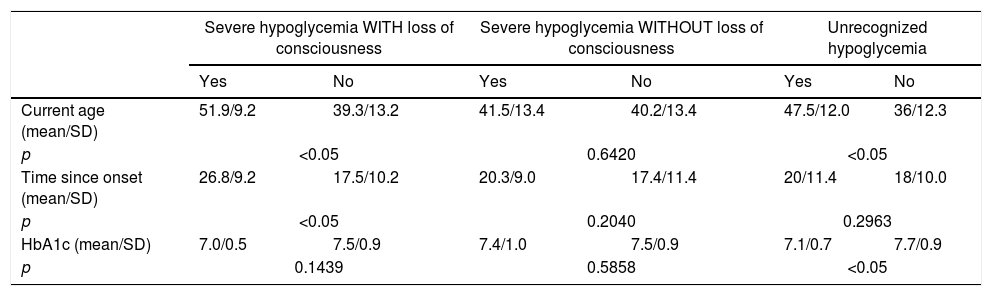

The presence of severe hypoglycemia with loss of consciousness was associated with older age and longer time since onset of the disease (Table 2). The presence of unrecognized hypoglycemia was associated with older age and lower HbA1c values (Table 2). No statistically significant association was found between severe hypoglycemia without loss of consciousness and age, time since onset, or HbA1c (Table 2).

Clinical characteristics referring to the presence of severe hypoglycemia with or without loss of consciousness and unrecognized hypoglycemia.

| Severe hypoglycemia WITH loss of consciousness | Severe hypoglycemia WITHOUT loss of consciousness | Unrecognized hypoglycemia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Current age (mean/SD) | 51.9/9.2 | 39.3/13.2 | 41.5/13.4 | 40.2/13.4 | 47.5/12.0 | 36/12.3 |

| p | <0.05 | 0.6420 | <0.05 | |||

| Time since onset (mean/SD) | 26.8/9.2 | 17.5/10.2 | 20.3/9.0 | 17.4/11.4 | 20/11.4 | 18/10.0 |

| p | <0.05 | 0.2040 | 0.2963 | |||

| HbA1c (mean/SD) | 7.0/0.5 | 7.5/0.9 | 7.4/1.0 | 7.5/0.9 | 7.1/0.7 | 7.7/0.9 |

| p | 0.1439 | 0.5858 | <0.05 | |||

No statistically significant differences were observed in the prevalence of severe hypoglycemia with or without loss of consciousness or unrecognized hypoglycemia according to the type of treatment or the blood glucose monitoring method used.

DiscussionOur study represents an attempt to highlight the magnitude of twoserious problems associated with the treatment of type 1 diabetes: unrecognized hypoglycemia and severe hypoglycemia with and without loss of consciousness.

The incidence and prevalence rates of severe hypoglycemia can differ greatly among the different studies of patients with type 1 diabetes due to a number of reasons.19 In this regard, on considering severe hypoglycemia as defined above, the incidence will be much higher than if we only assume severe hypoglycemia when urgent attention is required in hospital for the administration of glucagon or glucose via the intravenous route. Knowing whether a patient has experienced severe hypoglycemia is complicated. The opinion of a relative or companion can reveal hypoglycemic episodes not reported by the patient. Another factor affecting the results is the number of hypoglycemic episodes experienced by the patient, since hypoglycemia is usually downplayed when repeated episodes occur.21,22 Many of the studies reporting severe hypoglycemia rates have been carried out in the context of randomized controlled trials to evaluate new drugs. In these cases, methodological rigor is solid, but the inclusion and exclusion criteria used may imply that the final study population is not representative of the patients seen in the real-life setting.23

Our cohort allowed us to confirm that the prevalences of severe hypoglycemia without loss of consciousness (39.8% of our patients had had at least one such episode in the previous 6 months) and severe hypoglycemia with loss of consciousness (11.4% of our patients had had at least one such episode in the previous year) are very high and do not differ significantly from the data previously reported by other authors.19

The results of the DCCT study showed that more physiological treatment based on the use of multiple dose insulin or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, together with a diabetes education program aimed at securing better HbA1c values, was associated with a decrease in the risk of the occurrence or progression of complications associated with hyperglycemia. However, this same study showed that achieving stricter HbA1c targets was associated with a three-fold higher risk of severe hypoglycemic episodes.24

The presence of recurrent hypoglycemia secondary to insulin treatment in patients with type 1 diabetes has been related to an adaptive mechanism that allows patients to continue maintaining their brain activity despite experiencing manifest biochemical hypoglycemia.12 This mechanism, a priori of a protective nature, is nevertheless accompanied by a decrease or even loss of the ability of the patient to notice the situation of hypoglycemia. This defines it as a maladaptive mechanism, since the risk of severe hypoglycemic episodes is markedly increased as a result.1

In our study, the prevalence of patients with unrecognized hypoglycemia (40.9% of the analyzed individuals had unrecognized hypoglycemia according to the Clarke test) was higher than expected, but comparable to that reported in a population with a clearly different study methodology (patients with type 1 diabetes who recorded their answers through an online platform).25

In our study, the patients with unrecognized hypoglycemia had significantly lower HbA1c values than the patients without unrecognized hypoglycemia, and the dependence between unrecognized hypoglycemia and severe hypoglycemia with and without loss of consciousness was confirmed.

Different therapeutic options are currently available for restoring the ability of the patient to recognize situations of hypoglycemia and thus reduce the risk of severe hypoglycemia. All these therapeutic options seek to avoid repeated hypoglycemic episodes as far as possible through specific educational programs that help the patient to recognize hypoglycemia,16 the use of insulins associated with a lower risk of hypoglycemia, interstitial CGM, or integrated systems with the suspension of insulin infusion in predicting hypoglycemia.

However, the basic element for reducing the risk of severe hypoglycemia with or without loss of consciousness associated with the treatment of type 1 diabetes is the detection of patients at greater risk1.

In conclusion, patients with type 1 diabetes and recurrent hypoglycemia are at an increased risk of unrecognized hypoglycemia, which facilitates the occurrence of severe hypoglycemia with or without loss of consciousness. Our study has demonstrated the magnitude of this problem in our setting and the need to incorporate the evaluation of these aspects systematically into clinical practice, in order to plan possible necessary resources and select and prioritize the best resolution strategies adapted to the individual patient.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Thanks are due to the Research Unit of Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete (Spain) for its support in designing the study.

Please cite this article as: Pinés Corrales PJ, Arias Lozano C, Jiménez Martínez C, López Jiménez LM, Sirvent Segovia AE, García Blasco L, et al. Prevalencia de hipoglucemia grave en una cohorte de pacientes con diabetes tipo 1. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:47–52.