Hungry bone syndrome (HBS) is a complication occurring after parathyroid surgery that can cause severe and prolonged hypocalcemia. The study objective was to know the risk factors for HBS after surgery for primary hyperparathyroidism and its relationship with serum calcium and parathyroid hormone levels.

Material and methodsA case-control, observational, analytical study was conducted in patients who had undergone surgery for primary hyperparathyroidism in the past 10 years (2007–2016). Changes over time in serum calcium and PTH levels and the general characteristics of patients were analyzed.

ResultsThe incidence rate of HBS in our series was 12.2%. HBS was found to be significantly associated to thyroid surgery during the surgical procedure itself [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 17.241], to age older than 68 years (aOR = 6.666), and to lesions greater than 1.7 cm (aOR = 7.165). A statistically significant relationship was seen between presence of HBS and corrected serum calcium levels higher than the mean the day after surgery and one week and 3 months later, and also with PTH levels higher than the mean before, during, and one day after surgery.

ConclusionIn our series, independent risk factors for development of HBS included patient age, lesion size, and whether or not the procedure was accompanied by thyroid surgery, which requires closer monitoring of mineral metabolism during the perioperative period.

El síndrome del hueso hambriento (SHH) es una complicación tras la cirugía paratiroidea que puede causar una hipocalcemia grave y prolongada. El objetivo fue conocer los factores de riesgo de SHH después de la cirugía por hiperparatiroidismo primario y su relación con los niveles de calcio sérico y de hormona paratiroidea (PTH).

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un estudio analítico observacional de casos y controles en pacientes operados por hiperparatiroidismo primario en los últimos 10 años (2008–2017). Se estudió la evolución analítica del calcio, la PTH y las características generales de los pacientes.

ResultadosLa incidencia de SHH en nuestra serie fue del 12,2%. Se encontró una asociación significativa de SHH con la cirugía tiroidea en el mismo acto quirúrgico [odds ratio ajustada (ORa) = 17,241], con la edad mayor de 68 años (ORa = 6,666) y con el tamaño de la lesión mayor a 1.7 cm (ORa = 7.165). Observamos una relación estadísticamente significativa entre presentar SHH con un valor mayor a la media de calcio sérico corregido el día después de la cirugía, a la semana y a los 3 meses, así como con un valor mayor de la media de PTH preoperatoria, en la cirugía y un día después de la cirugía.

ConclusiónLos factores de riesgo independientes para el desarrollo de SHH en nuestra serie fueron la edad del paciente, el tamaño de la lesión y si la intervención se acompaña de cirugía tiroidea, lo que obliga a una monitorización más estrecha del metabolismo mineral durante el perioperatorio.

One of the possible complications of parathyroid surgery is hungry bone syndrome (HBS). This syndrome manifests when the correction of primary hyperparathyroidism (PHP) is associated with rapid bone remineralization, causing severe and prolonged hypocalcemia.1 The fall in serum calcium is essentially due to functional or relative hypoparathyroidism occurring after surgery and secondary to increased calcium uptake by bone, urinary calcium excretion (in patients without renal failure), and decreased intestinal calcium absorption due to a decrease in 1-25-dihydroxycholecalciferol mediated by parathyroid hormone (PTH).1 In other words, following parathyroidectomy, PTH stimulation abruptly ceases and excessive osteoclastic activity is stopped, but osteoblastic activity continues, resulting in a marked increase in bone calcium uptake to facilitate bone formation. This predisposes the patient to symptomatic hypocalcemia with so-called HBS.2

In some patients with HBS, particularly those with preoperative bone disease, postoperative hypocalcemia is severe and prolonged despite the maintenance of normal or even high PTH levels after surgery. In addition to the drop in serum calcium, a decrease in serum phosphate and an increase in serum potassium levels may also occur.3

According to the literature, HBS occurs in approximately 12–30% of all patients after parathyroid surgery, with the most common cause being an adenoma producing PHP−.

The lack of well-defined clinical criteria for the diagnosis of HBS makes it difficult to determine the true incidence of the syndrome, since hypocalcemia is generally transient, the degree of bone disease is usually mild, and the normal parathyroid tissue recovers function quickly (generally within a week), even after prolonged suppression.4

Defining the biochemical values for diagnosing HBS and knowing the possible risk factors could contribute to patients not being overtreated postoperatively and also help predict which individuals may develop the disease. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to determine which patients are at risk of developing postoperative HBS, the clinical and biochemical characteristics and their course being assessed over time.

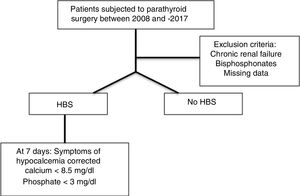

Material and methodsAn observational case-control analytical study was made of patients subjected to parathyroid surgery due to primary hyperparathyroidism over a 10-year period (2008–2017).

Surgery for primary hyperparathyroidism was performed in symptomatic patients (nephrolithiasis or symptoms related to hypercalcemia) and asymptomatic individuals meeting one of the following criteria: serum calcium >11.5 mg/dl, skeletal involvement with asymptomatic vertebral fractures or alterations in bone density (if evaluated), renal impairment as assessed by an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <60 ml/min or 24-h urine calcium >400 mg/day and an age of <50 years.

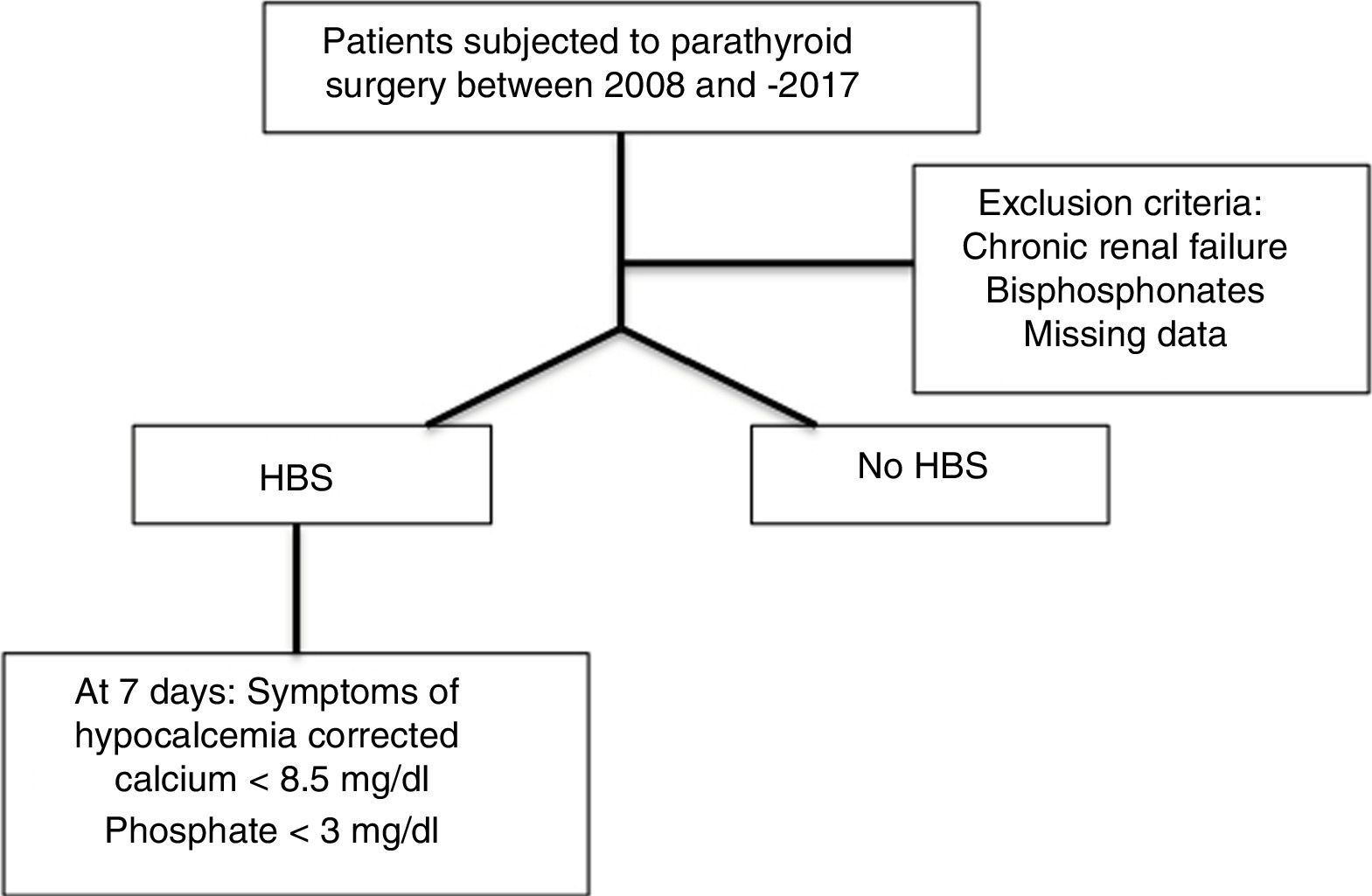

Cases were defined as patients who presented HBS based on clinical and biochemical criteria at 7 days after surgery. Hypocalcemia was defined as corrected serum calcium concentration <8.5 mg/dl. In addition to hypocalcemia, the patients were required to present serum phosphate levels <3.0 mg/dl. Hypomagnesemia and hyperpotassemia could also be present but were not considered strict diagnostic criteria.

The exclusion criteria comprised chronic renal failure in any stage, treatment with bisphosphonates before surgery, and the absence of any biochemical data during follow-up referring to calcium, phosphorus or PTH. Anatomical variants, other simultaneous surgeries or patient comorbidities were not regarded as exclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

Clinical and biochemical data were collected through the electronic health records. The variables collected included patient age and gender, the location of the affected gland, the histopathological diagnosis, lesion size and weight, the diagnosis of HBS, calcium, PTH, the phosphorus, magnesium and potassium levels determined preoperatively, on the day after surgery and one week and three and 6 months after surgery, and the need or not for replacement therapy with calcium and vitamin D during the postoperative period.

In patients with HBS and corrected calcium ≤7.5 mg/dl, intravenous calcium was administered as a slow infusion (6 ampoules of 10 ml containing 10% calcium gluconate in 500 ml of physiological saline at a rate of 50 ml/h). Daily laboratory tests were performed, and when the serum calcium levels reached 7.5−8 mg/dl, treatment was started with oral calcium and vitamin D, with subsequent follow-up at the Endocrinology clinic until normalization.

In patients without HBS presenting mild symptoms and/or serum calcium levels 7.5−8.5 mg/dl, treatment was provided with oral calcium and vitamin D until normalization.

All the patients treated with calcium and vitamin D were prescribed calcium carbonate 1250 mg every 8 h (1500 mg of elemental calcium daily) and calcitriol 0.25 μg daily.

The database was analyzed using the IBM© Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) © version 22 statistical package for OS X©. A descriptive analysis was made, based mainly on the frequency distribution and basic summary statistics with their dispersion measures. Bivariate analysis was performed using the Pearson χ² test, while the comparison of means was based on the Mann–Whitney U-test. The quantitative variables were previously shown to exhibit a non-normal distribution based on the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Lastly, multiple logistic regression analysis was performed, with the dependent variable being the diagnosis of HBS and the independent or predictive variables being those found to be significant in the bivariate analyses.

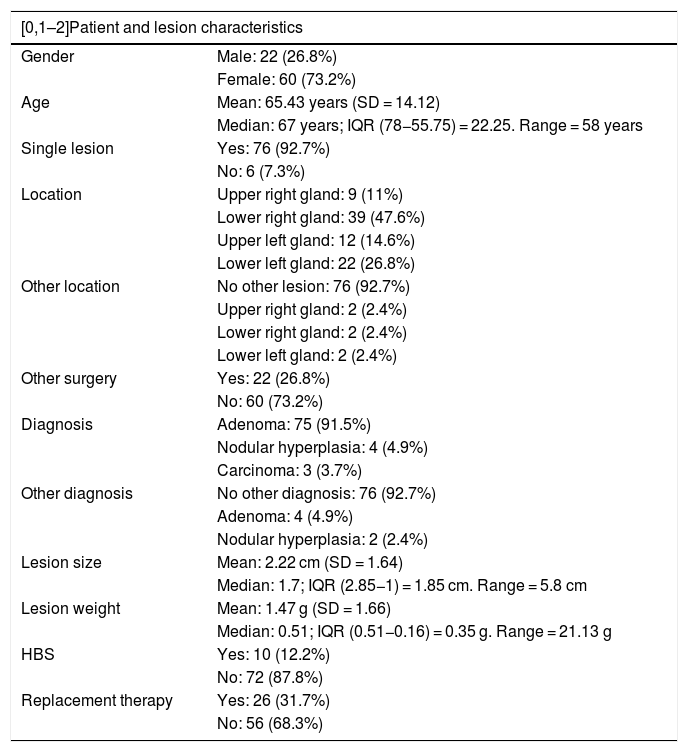

ResultsA total of 82 patients subjected to parathyroidectomy due to primary hyperparathyroidism were studied: 22 males (26.8%) and 60 females (73.2%). The mean age was 65.15 years (SD = 14.12), and the median age was 67 years (interquartile range [IQR] 22.25 years). Six patients (7.6%) had more than one affected parathyroid gland. The most common tumor location was in the lower right gland (47.6%), followed by the lower left gland (26.8%). Twenty-two patients (26.8%) simultaneously underwent other surgery in the form of hemithyroidectomy or total thyroidectomy (Table 1).

General characteristics of the patients enrolled in the study.

| [0,1–2]Patient and lesion characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Gender | Male: 22 (26.8%) |

| Female: 60 (73.2%) | |

| Age | Mean: 65.43 years (SD = 14.12) |

| Median: 67 years; IQR (78−55.75) = 22.25. Range = 58 years | |

| Single lesion | Yes: 76 (92.7%) |

| No: 6 (7.3%) | |

| Location | Upper right gland: 9 (11%) |

| Lower right gland: 39 (47.6%) | |

| Upper left gland: 12 (14.6%) | |

| Lower left gland: 22 (26.8%) | |

| Other location | No other lesion: 76 (92.7%) |

| Upper right gland: 2 (2.4%) | |

| Lower right gland: 2 (2.4%) | |

| Lower left gland: 2 (2.4%) | |

| Other surgery | Yes: 22 (26.8%) |

| No: 60 (73.2%) | |

| Diagnosis | Adenoma: 75 (91.5%) |

| Nodular hyperplasia: 4 (4.9%) | |

| Carcinoma: 3 (3.7%) | |

| Other diagnosis | No other diagnosis: 76 (92.7%) |

| Adenoma: 4 (4.9%) | |

| Nodular hyperplasia: 2 (2.4%) | |

| Lesion size | Mean: 2.22 cm (SD = 1.64) |

| Median: 1.7; IQR (2.85−1) = 1.85 cm. Range = 5.8 cm | |

| Lesion weight | Mean: 1.47 g (SD = 1.66) |

| Median: 0.51; IQR (0.51−0.16) = 0.35 g. Range = 21.13 g | |

| HBS | Yes: 10 (12.2%) |

| No: 72 (87.8%) | |

| Replacement therapy | Yes: 26 (31.7%) |

| No: 56 (68.3%) | |

Ten patients (12.2%) were diagnosed with HBS. Of the total patients, 27 (32.9%) received treatment with calcium and vitamin D in the postoperative period, and the treatment in patients with HBS was provided via the intravenous route (Table 1).

The most common postoperative histopathological diagnosis was parathyroid adenoma in 75 patients (91.5%), nodular hyperplasia in four patients (4.9%), and parathyroid carcinoma in three patients (3.7%). The mean lesion weight was 1.47 g (SD = 3.90), with a median weight of 0.51 g (IQR 0.35 g). The mean lesion size was 2.22 cm (SD = 1.64), with a median size of 1.7 cm (IQR 1.85 cm) (Table 1).

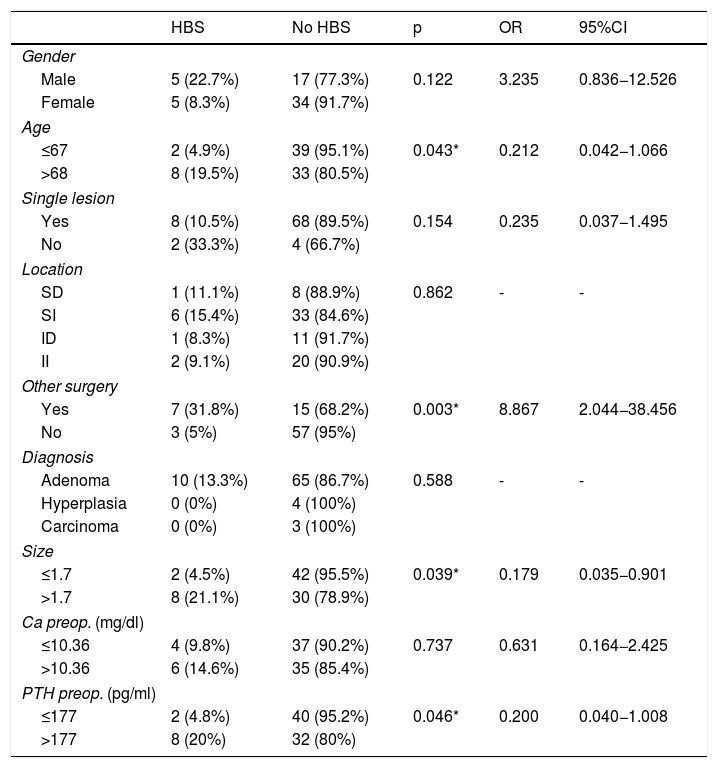

A total of 5 males (22.7%) presented HBS versus 5 females (8.3%), with no statistically significant gender difference (Table 2).

Relationship between gender, age, anatomical characteristics and biochemical parameters, and HBS.

| HBS | No HBS | p | OR | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 5 (22.7%) | 17 (77.3%) | 0.122 | 3.235 | 0.836−12.526 |

| Female | 5 (8.3%) | 34 (91.7%) | |||

| Age | |||||

| ≤67 | 2 (4.9%) | 39 (95.1%) | 0.043* | 0.212 | 0.042−1.066 |

| >68 | 8 (19.5%) | 33 (80.5%) | |||

| Single lesion | |||||

| Yes | 8 (10.5%) | 68 (89.5%) | 0.154 | 0.235 | 0.037−1.495 |

| No | 2 (33.3%) | 4 (66.7%) | |||

| Location | |||||

| SD | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (88.9%) | 0.862 | - | - |

| SI | 6 (15.4%) | 33 (84.6%) | |||

| ID | 1 (8.3%) | 11 (91.7%) | |||

| II | 2 (9.1%) | 20 (90.9%) | |||

| Other surgery | |||||

| Yes | 7 (31.8%) | 15 (68.2%) | 0.003* | 8.867 | 2.044−38.456 |

| No | 3 (5%) | 57 (95%) | |||

| Diagnosis | |||||

| Adenoma | 10 (13.3%) | 65 (86.7%) | 0.588 | - | - |

| Hyperplasia | 0 (0%) | 4 (100%) | |||

| Carcinoma | 0 (0%) | 3 (100%) | |||

| Size | |||||

| ≤1.7 | 2 (4.5%) | 42 (95.5%) | 0.039* | 0.179 | 0.035−0.901 |

| >1.7 | 8 (21.1%) | 30 (78.9%) | |||

| Ca preop. (mg/dl) | |||||

| ≤10.36 | 4 (9.8%) | 37 (90.2%) | 0.737 | 0.631 | 0.164−2.425 |

| >10.36 | 6 (14.6%) | 35 (85.4%) | |||

| PTH preop. (pg/ml) | |||||

| ≤177 | 2 (4.8%) | 40 (95.2%) | 0.046* | 0.200 | 0.040−1.008 |

| >177 | 8 (20%) | 32 (80%) | |||

Ca preop.: preoperative calcium; ID: lower right; II: lower left; PTH preop.: preoperative PTH; SD: upper right; HBS: hungry bone syndrome; SI: upper left.

The mean age of the patients with HBS was greater than that of the patients without HBS, though the difference was not statistically significant. The variable age was grouped by median into two groups: patients aged 67 years or younger, and patients aged 68 years or older. Two patients (4.9%) in the former group (≤67 years of age) presented HBS versus 8 (19.5%) in the latter group (≥68 years of age), the difference being statistically significant (p = 0.042), with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.212 and a 95% confidence interval (95%CI) of 0.042−1.066 (Table 2).

Of the patients with a lesion in a single gland, 8 (10.5%) presented HBS versus two (33.3%) of those with more than one affected gland, the difference failing to reach statistical significance (Table 2).

No statistically significant differences were found between the location of the main lesion and the type of definitive diagnosis of the specimen with the diagnosis of HBS (Table 2).

Of the patients that also underwent thyroid surgery, 7 (31.8%) presented HBS versus three (5%) of those subjected to parathyroid surgery alone; the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.003), with an OR of 8.867 and 95%CI 2.044−38.456 (Table 2).

A statistically significant difference was observed between lesion size and HBS, though no relationship was found with lesion weight. On grouping of the variable size according to the median into two groups, we found two patients (4.5%) with a lesion measuring 1.7 cm or less in size to have HBS versus 8 patients (21.1%) with a lesion larger than 1.7 cm, the difference being statistically significant (p = 0.039), with an OR of 0.179 and 95%CI 0.035−0.901 (Table 2).

No statistically significant difference was found between preoperative serum calcium and HBS, though a statistically significant difference was found between preoperative PTH and HBS. On grouping PTH according to the median, two patients (4.8%) with preoperative PTH ≤ 177 pg/ml developed HBS versus 8 patients (20%) with PTH > 177 pg/ml, the difference being statistically significant, with an OR of 0.200 and 95%CI 0.040−1.008 (Table 2).

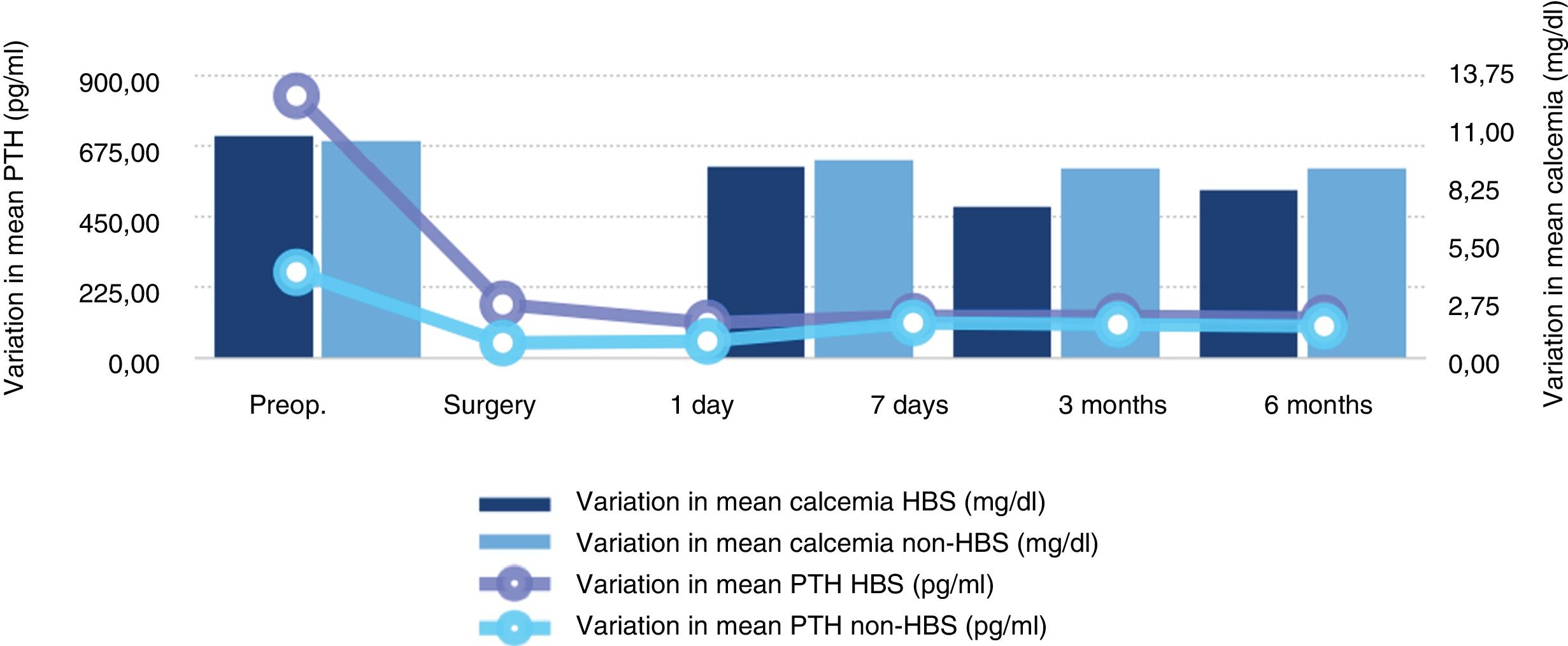

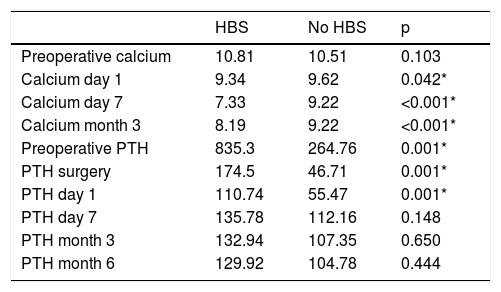

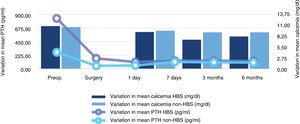

Variation of the biochemical parametersA statistically significant difference was found between patients with HBS and those without HBS in relation to corrected serum calcium concentration on the day after surgery and at one week and three months, and to PTH concentration determined preoperatively, at surgery, and on the day after surgery (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Variation over time in mean serum calcium (mg/dl) and mean PTH (pg/ml).

| HBS | No HBS | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative calcium | 10.81 | 10.51 | 0.103 |

| Calcium day 1 | 9.34 | 9.62 | 0.042* |

| Calcium day 7 | 7.33 | 9.22 | <0.001* |

| Calcium month 3 | 8.19 | 9.22 | <0.001* |

| Preoperative PTH | 835.3 | 264.76 | 0.001* |

| PTH surgery | 174.5 | 46.71 | 0.001* |

| PTH day 1 | 110.74 | 55.47 | 0.001* |

| PTH day 7 | 135.78 | 112.16 | 0.148 |

| PTH month 3 | 132.94 | 107.35 | 0.650 |

| PTH month 6 | 129.92 | 104.78 | 0.444 |

All patients with HBS (12.2%) received replacement therapy after diagnosis.

Among the patients not meeting HBS criteria (87.8%), 17 received replacement therapy with calcium and oral vitamin D during the first week after surgery.

Among the patients not diagnosed with HBS, the mean corrected serum calcium concentration one week after surgery was 8.49 mg/dl in the presence of calcium and vitamin D treatment during the first week, versus 9.44 mg/dl in the absence of calcium and vitamin D treatment, with a mean difference of 0.95 mg/dl between the two groups. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Mann–Whitney U-test).

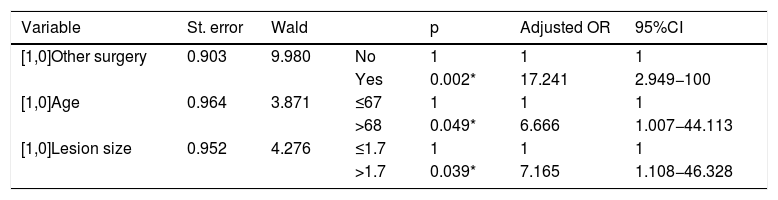

Multivariate analysisLastly, logistic regression analysis established a significant association between thyroid surgery performed in the same operation (with an adjusted OR of 17.241 and 95%CI 2.949−100), age over 68 years (with an adjusted OR of 6.666 and 95%CI 1.007−44.113) and lesion size over 1.7 cm (with an adjusted OR of 7.165 and 95%CI 1.108−46.328) (Table 4).

Logistic regression model, with the diagnosis of HBS as dependent variable.

Hungry bone syndrome is a complication that can manifest after parathyroid surgery due to primary hyperparathyroidism. This syndrome develops as a result of the high bone turnover that can occur after surgery in these patients.1 It is characterized by rapid, profound and persistent hypocalcemia associated with hypophosphatemia, hypomagnesemia and suppressed PTH levels.

The prolongation of HBS over time is conditioned by the speed of recovery of bone remineralization. This is reflected by normalization of the bone turnover markers, improvement of the radiological characteristics, and significant bone mass gain.4

The evidence in the literature on HBS is scarce, despite the fact that this is a prevalent syndrome associated with significant clinical and biochemical alterations that pose a patient management challenge.

Hungry bone syndrome is estimated to affect up to 13% of all patients with PHP.4–6 However, there are case series in Asian patients with higher rates ranging from 24 to 87%,5,7 as well as others with much lower rates, such as that reported in Saudi Arabia, with an incidence of 4%.5,8 In our study the incidence of HBS was 12.2%, which agrees with the current literature.

We observed no greater prevalence in women versus men, in contrast to other studies that report a female predominance.3–6

The lowering of serum calcium levels usually occurs between two and four days after surgery, and may be at its maximum one week after surgery. For this reason we took into consideration the evaluation of corrected serum calcium concentration one week after surgery. It is important to take into account that hypocalcemia in the first four days after surgery may be due to intentional or accidental elimination of all the parathyroid glands, the disruption of vascularization, trauma to the residual parathyroid glands, or the suppression of non-pathological parathyroid glands, without the development of HBS.1,5

Intravenous replacement therapy with calcium and vitamin D was prescribed in all patients with HBS, once diagnosed. A total of 17 patients were prescribed oral replacement therapy in the first week due to low or borderline calcium levels, without meeting the criteria of HBS. All of these patients presented a serum corrected calcium value 1 mg/dl lower than those who did not receive treatment. We do not know whether the patients that started treatment with oral calcium and vitamin D in the first week after surgery would have developed HBS if supplementing had not been provided.

A number of factors can increase the risk of HBS. Brasier et al.4 identified the following predictors of the development of the syndrome (in descending order of importance): resected adenoma volume, preoperative blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentration, preoperative alkaline phosphatase concentration, and advanced age.

Mittendorf et al.9 also identified as risk factors the presence of high preoperative calcium and PTH levels, as well as the presence of osteitis fibrosis cystica.

In our study we found the size of the removed parathyroid gland to be a risk factor, the gland being larger in patients with HBS than in those with a normal postoperative period (4.08 versus 1.96 cm, respectively). Zamboni et al.5 also found that 11 out of 16 patients with adenoma >2 g developed transient postoperative hypocalcemia versus 3 out of 21 patients with adenoma <1 g. A patient age of over 68 years at the time of surgery – the median age and cut-off point of our sample due to the asymmetry of the variable – was also identified as a risk factor for HBS. Advanced age is associated with vitamin D deficiency, a decrease in renal 1α-hydroxylase activity, and a lower dietary calcium intake, three factors that may potentially contribute to a negative calcium balance and the development of clinical bone disease.5

We also found mean PTH concentration to be greater in patients with HBS than in individuals with a normal postoperative period, the PTH levels being up to four times higher in the former subjects. No data were available on the preoperative alkaline phosphatase or urea nitrogen levels to establish whether high values may influence the development of HBS, as reported by other authors.10

We found that patients subjected to thyroid surgery in the same surgical procedure had a greater risk than patients subjected to parathyroid surgery alone, in agreement with the observations of Kaya et al.11 Such patients therefore should undergo very strict perioperative monitoring. Although it is true that HBS may occur due to damage to the remaining non-pathological parathyroid glands, it has been reported that the syndrome may develop after the surgical treatment of hyperthyroidism.12

The literature describes a rapid decrease in serum PTH levels to an average of over 17 pg/ml after parathyroidectomy.4 In our series we observed a mean decrease in PTH in each group of patients at the time of the removal of the affected gland, the PTH value being higher in the patients with HBS than in those without the syndrome. However, the mean decrease in PTH in each group was similar: 80% in the cases and 82% in the controls. The PTH levels during patient follow-up tended to become equal.

We observed no significant difference in preoperative serum calcium levels with the development of HBS, in concordance with the results published by Lee et al.13 It is known that in patients with HBS, the postoperative serum calcium levels drop to under 8.5 mg/dl in the first 3–4 days, and fall even further after the fourth postoperative day.4,14–16 During the first postoperative day we found the serum calcium levels to be lower in the HBS group than in the patients with a normal postoperative period. At one week this difference was seen to increase, but then it gradually decreased over time.

Although no data were available for analyzing bone remodeling markers, densitometry values, urea nitrogen, and 25-OH-vitamin D, our study does offer an idea of what has been happening to patients of this kind in recent years in our hospital, and may serve to define the lines to be followed in the future. We thus aim to be able to assess the potential beneficial effects of preoperative treatment with vitamin D and bisphosphonates,17 since no prospective studies or randomised clinical trials have yet evaluated the use of preoperative medication seeking to prevent or limit the duration of HBS, to measure the existence of radiological bone disease as a risk factor for HBS,18 and in the future to establish a risk predictor scale for HBS in patients subjected to parathyroidectomy due to PHP.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Guillén Martínez AJ, Smilg Nicolás C, Moraleda Deleito J, Guillén Martínez S, García-Purriños García F. Factores de riesgo y evolución del calcio y hormona paratiroidea en el síndrome de hueso hambriento tras paratiroidectomía por hiperparatiroidismo primario. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2020;67:310–316.