Amiodarone is a class III antiarrhythmic drug widely used in our setting for the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias. It is a benzofuran derivative with high iodine content, which can have a bearing on thyroid function at different levels (hypophysis, thyroid and peripheral receptors). In many cases, it can modify the circulating concentrations of thyroid hormones and be accompanied by both hypo- and hyperthyroidism, although the majority of patients remain euthyroid.1,2

The first-line treatment of amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism is fundamentally medical with synthetic antithyroid drugs In the case of Type 1 thyrotoxicosis (iodine induced), or with glucocorticoids in type II (owing to glandular destruction). Other less conventional drugs include potassium perchlorate and cholestyramine.3,4 Plasmapheresis has occasionally been used in cases of intolerance to antithyroid drugs, refractory hyperthyroidism, and to achieve euthyroidism prior to thyroidectomy, though clinical experience is scant.5

We present the case of a patient with structural cardiopathy with severe amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism refractory to medical treatment which required a high number of plasmapheresis cycles prior to definitive treatment with thyroidectomy.

53-year-old male with Arterial hypertension, dyslipidaemia, obesity, sleep apnoea syndrome, and persistent anticoagulated atrial fibrillation, owing to which he had received treatment with amiodarone (200 mg/day) over 3 years, with the suspension thereof in the 2 months prior to admission, at which time it was replaced by bisoprolol.

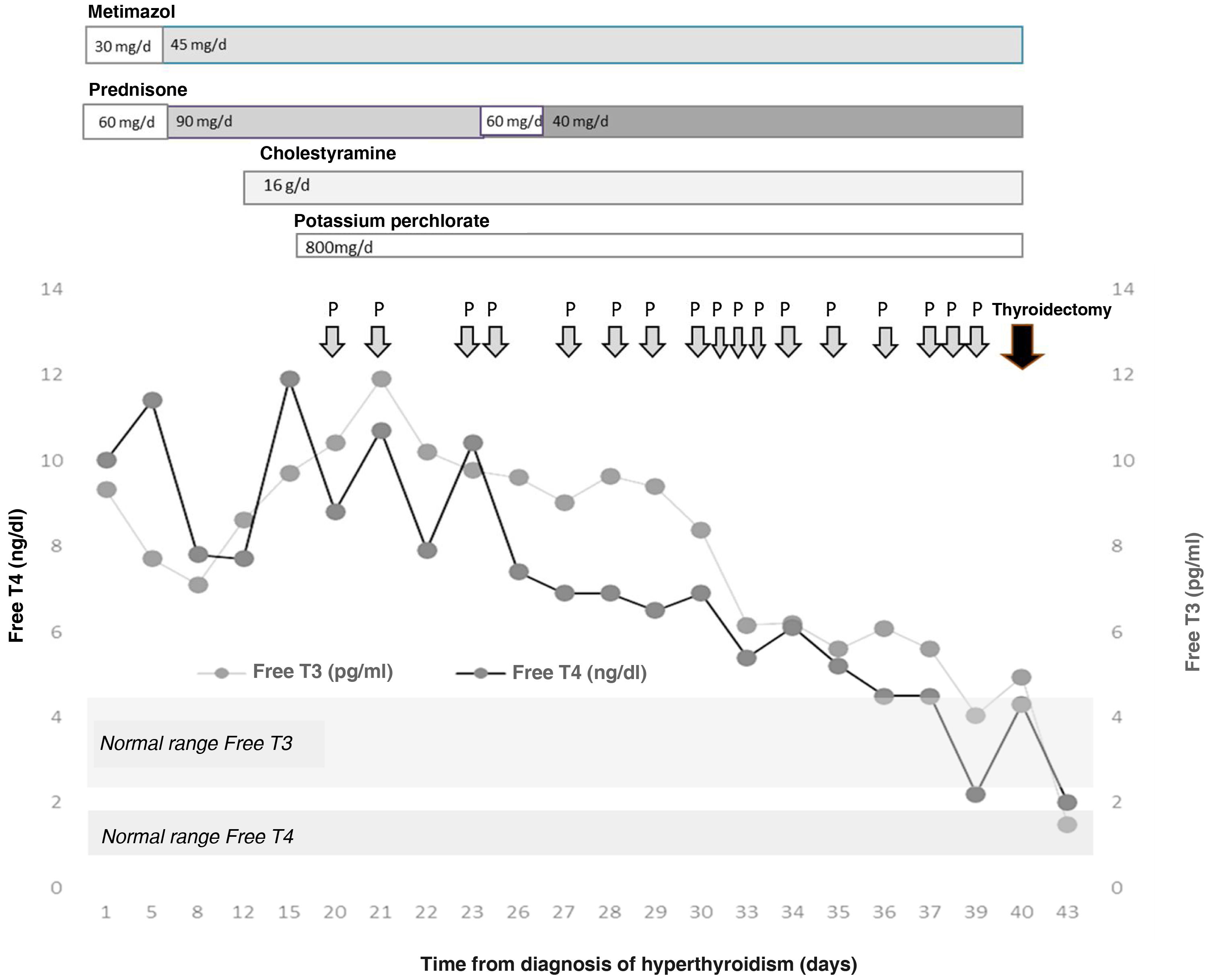

The patient was admitted for a preferential coronary angiography owing to chest pain with elevated markers of cardiac damage, which turned out to be normal. A study with transthoracic echocardiography was completed, showing a severely dilated right ventricle and data on severe pulmonary hypertension, as well as the existence of a superior sinus venosus atrial septal defect, with indication of non-urgent surgical closure. During admission, a severe overt hyperthyroidism was discovered (TSH < 0.01 μIU/mL, normal range [NR]: 0.35–5.0; Free T4 [FT4] 10.03 ng/dl, NR: 0.7–1.98, and Free T3 [FT3] 9.3 pg/mL, NR: 2.3–4.2) one week before the catheterisation was to be performed, without having previously presented exposure to iodised contrast agents. Clinically, he did not report palpitations, tremor, nervousness, or any other symptom of thyroid hyperfunction. He presented with good blood pressure and heart rate control with beta blockers. A grade 2 goitre, with no nodules was palpable. The thyroid echography showed a normal-sized gland with decreased vascularisation. The thyroid autoimmunity study was negative and the Interleukin-6, normal (<2.7 pg/mL, NR: 0.0–4.4). In light of these findings and suspected amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism, treatment was started with metimazol (30 mg/day) and prednisone (60 mg/day). During admission, the patient presented increasing serum levels of thyroid hormones, which made it necessary to increase the dose of metimazol (45 mg/day) and prednisone (90 mg/day) (Fig. 1). Acholestyramine (16 g/day) and potassium perchlorate (800 mg/day) were also associated. Despite this and, after supervising the proper adherence to the treatment, after three weeks the severe hyperthyroidism persisted (TSH < 0.01 μIU/mL, FT4 11.92 ng/dl and FT3 9.76 pg/mL) with the diagnosis of severe amiodrone-induced hyperthyroidism refractory to high doses of metimazol, corticosteroids, cholestyramine and potassium perchlorate being established, owing to which total thyroidectomy was proposed as definitive treatment. After discussing the case in a multi-disciplinary session with Cardiac Surgery, Cardiology, Anaesthesia, General Surgery and Endocrinology, it was decided to first perform a total thyroidectomy and, secondly, the closure of the ASD. With the aim of reducing perioperative cardiovascular risk, treatment with plasmapheresis was initiated with the aim of achieving euthyroid status.

The plasmapheresis sessions consisted of mixed plasma exchanges of albumin/plasma of 1.5 volumes in each session, performed by the Haematology Department using an apheresis machine. By way of complications, the patient presented various episodes of skin rash which required prophylactic antihistamine treatment with each exchange. During the procedure, a slight tendency towards anaemisation was observed (nadir of haemoglobin 11.2 g/dl, NR: 12.0–17.0 g/dl; after the 11th session of plasmapheresis, 13 days after its commencement) which required no treatment. An asymptomatic hypocalcaemia was also observed, despite intravenous supplementation with calcium gluconate (nadir of 7.6 mg/dl; NR: 8.7–10.3 mg/dl). All of these complications were resolved after concluding the plasmapheresis.

Given the difficulty to attain a reduction in circulating thyroid hormones, a total of 17 were performed prior to surgery. At no time was the additional medical treatment suspended, although the dose of prednisone was reduced to 40 mg/day. Serum levels of thyroid hormones were also determined on 5 occasions before and after the session of plasmapheresis, achieving a reduction of their levels in the extraction sample immediately post-plasmapheresis (FT4 pre- vs. post-plasmapheresis 7.89 ± 2.48 vs. 4.58 ± 1.35 ng/dl, P = .009; reduction of 41.9% and FT3 pre- vs. post-plasmapheresis 8.60 ± 2.46 vs. 8,24 ± 2.17 pg/mL, P = .157; reduction of 4.1%), with a further increase on the day after plasmapheresis (FT4 following day 6.73 ± 1.07 ng/dl, P = .001; increase of 46.94% and FT3 following day 8.25 ± 2.15 pg/mL, P = .950; increase of 0.1%).

Finally, total thyroidectomy was performed 40 days after the initial diagnosis of hyperthyroidism, without incident. The thyroid profile prior to surgery was TSH 0.01 μIU/mL, FT4 4.33 ng/dl and FT3 4.95 pg/mL. On the day immediately after, a reduction in the FT4 to 3.88 ng/dl was noted, falling to values of 1.98 ng/dl 3 days after the intervention. Given the absence of post-surgical complications, and the rapid normalisation of the thyroid hormones, the patient was discharged with hormone replacement therapy with 150 µg of levothyroxine a day.

Therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) Is a treatment rarely used for the control of hyperthyroidism. The Blood Bank (Haematology and Haemotherapy Department) was responsible for its implementation, requiring for the procedure afferent and efferent lines connected to the apheresis equipment. Its usefulness is based on the binding of T3 and T4 to plasma proteins that are eliminated. By decreasing their plasma concentration, the hormonal concentration is reduced (principally T4, with a lower free fraction). Additionally, by using fresh plasma as replacement fluid, these proteins are applied allowing the binding of the free hormone.6

Its indication in hyperthyroidism is not clearly established. Some authors consider that TPE could be useful in the thyrotoxic storm, in cases of intolerance or refractoriness to conventional treatments, and as preoperative preparation,7 its most frequent indication being Graves' disease, followed by amiodarone-Induced hyperthyroidism.8 Its complications include bleeding, infection, arterial hypotension, hypocalcaemia and skin reactions. The most serious correspond to disseminated intravascular coagulation or pulmonary thromboembolism, with a mortality <1%.9,10 In our patient, all the complications were mild and self-limiting.

Although there are studies in which 4–6 TPE sessions were necessary for normalising thyroid hormones5,11 in our case, this rose to 17. The analytical alteration was clearly more pronounced in the other series, with exposure to the iodinated contrast agents of the catheterisation also possibly making control more difficult. After reviewing the literature, this case would seem to be the greatest number of plasmapheresis that have been received before definitive treatment. Moreover, each session significantly reduced the FT4, practically without affecting the FT3; however, this reduction was transient, with a significant increase after 24 h, which justified the repetition of sessions. During the evolution, it was difficult to discern the net effect of the drug therapy and the plasmapheresis in controlling the hyperthyroidism. Although there was no reduction in thyroid hormones until the TPE was started, which could reflect the efficacy of this technique.

In conclusion, plasmapheresis would seem to be an effective alternative in those cases of severe amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism refractory to conventional medical treatment at maximum doses as preparation for definitive treatment with surgery.

FundingThe authors declare that no type of funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.