Sarcopenic dysphagia, defined as dysphagia caused by sarcopenia, is a swallowing disorder of great interest to the medical community. The objective of our study was to evaluate the prevalence and factors associated with sarcopenic dysphagia in institutionalised older adults.

Material and methodsAn observational, analytical, cross-sectional study was conducted in a nursing home between September and December 2017, with 100 participants. The presence of dysphagia was assessed using the volume-viscosity clinical examination method, and the diagnostic algorithm for sarcopenic dysphagia was followed. The participants’ grip strength, gait speed, calf circumference, nutritional assessment (Mini Nutritional Assessment), Barthel Index, cognitive assessment (Mini-Mental State Examination) and Charlson Comorbidity Index were evaluated. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed.

ResultsThe median age was 84 years, and 55% were women; 48% had functional dependence, 49% had positive screening for malnutrition and 64% had some degree of dysphagia. The prevalence of sarcopenic dysphagia was 45%, and the main factors related to less sarcopenic dysphagia were a good nutritional status (OR 0.85, 95% CI, 0.72−0.99) and a better functional performance status (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.97−0.98).

ConclusionSarcopenic dysphagia has a high prevalence in institutionalised older adults; and functional dependence and poor nutritional status were associated with sarcopenic dysphagia.

La disfagia sarcopénica, definida como la disfagia causada por la sarcopenia, es un trastorno de la deglución de gran interés para la comunidad médica. El objetivo de nuestro trabajo fue evaluar la prevalencia y los factores asociados con disfagia sarcopénica en adultos mayores institucionalizados.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional, analítico, transversal, realizado en un hogar geriátrico entre septiembre y diciembre del 2017, con 100 participantes. Se valoró la presencia de disfagia mediante el método de exploración clínica volumen-viscosidad y se siguió el algoritmo diagnóstico para disfagia sarcopénica. Se evaluó fuerza de agarre, velocidad de la marcha, perímetro de pantorrilla, evaluación nutricional (Mini Nutritional Assessment), índice de Barthel, evaluación cognitiva (Mini-Mental State Examination) e índice de comorbilidad de Charlson. Se realizaron análisis bivariados y multivariados de regresión logística.

ResultadosLa mediana de edad fue de 84 años y el 55% eran mujeres. El 48% presentó dependencia funcional, el 49% tenía cribado positivo para desnutrición y el 64% tuvo algún grado de disfagia. La prevalencia de disfagia sarcopénica fue del 45% y los principales factores relacionados con menos disfagia sarcopénica fueron un buen estado nutricional (OR = 0,85, IC del 95%, 0,72–0,99) y un mejor estado funcional (OR = 0,98, IC del 95%, 0,97−0,98).

ConclusiónLa disfagia sarcopénica tiene una alta prevalencia en adultos mayores institucionalizados y las variables asociadas fueron la dependencia funcional y un pobre estado nutricional.

Oropharyngeal dysphagia is defined as a gastrointestinal motility disorder that renders safe movement of a food bolus from the mouth to the stomach difficult or impossible.1 One factor associated with dysphagia is sarcopenia, defined according to the 2018 European consensus based on muscle strength (probable sarcopenia); to confirm its diagnosis, there is an established algorithm that also involves evaluation of muscle quantity and quality (confirmed sarcopenia) and physical performance (severe sarcopenia).2

Swallowing disorders are an emerging problem and have become one of the most significant challenges in geriatrics. The prevalence of dysphagia in older adults (OAs) is high;3 it affects around 27% of OAs living in the community.4 This figure rises to 47.4% among OAs admitted to an Acute Care Geriatric Unit, according to a study conducted by Carrión et al.,3 and 51% among institutionalised OAs, according to a study conducted by Lin et al.5 on a long-term care unit in Taiwan.

Dysphagia has a major impact on health and causes nutritional and respiratory complications associated with hospitalisation, hospital readmissions, institutionalisation, poor quality of life and death.3–6 However, due to lack of knowledge of this condition, in many cases it is neither diagnosed nor treated, and only a minority of OAs receive a diagnosis and suitable treatment.7,8

Both dysphagia and sarcopenia are listed in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) as separate diseases (R13 and M62.84, respectively),9 and the link between these two conditions has been reported in recent years.10–12 Recently, a meta-analysis by Zhao et al.13 found that the risk of dysphagia is higher in patients with sarcopenia compared to patients without sarcopenia (odds ratio [OR] = 4.06, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.27–7.29).

Thus the concept of sarcopenic dysphagia emerged in 2012. It was first reported by Kuroda and Kuroda,14 who, in their study conducted at Saint Francis Hospital in Japan, established a correlation between arm circumference (as an indicator of undernutrition) and swallowing function. They reported how dysphagia caused by sarcopenia affects all the muscles of the body, including the muscles involved in swallowing. In 2014, the same authors proposed diagnostic criteria. In 2017, Mori et al.15 published the diagnostic algorithm including measurement of sarcopenia and assessment of swallowing function. The algorithm indicates that cases in which dysphagia is suspected of being secondary to another aetiology should be ruled out and that sarcopenic dysphagia should not be diagnosed if sarcopenia is not present.15

Sarcopenic dysphagia has become a topic of great interest to the medical and scientific community in recent years. There are reported cases of sarcopenic dysphagia after acute events such as lung cancer surgery16 and glossectomy.17 Its diagnosis is important as it represents an increased risk of related complications, such as aspiration pneumonia, dehydration and undernutrition.18 Aspiration pneumonia can even be classified as resulting from sarcopenic dysphagia, being associated with decreased quality of life and increased health costs.19 The institutionalised OA population usually shows higher rates of dependence, sarcopenia, morbidity and neurological and degenerative diseases that could cause dysphagia.8 Despite this, the literature is devoid of studies evaluating the prevalence and factors associated with sarcopenic dysphagia in this population.

The above inspired the objective of this study, which was to determine the prevalence and factors associated with sarcopenic dysphagia in a population of institutionalised OAs.

Material and methodsPopulation and designThis was an observational, analytical, cross-sectional study conducted in a nursing home between September and December 2017. For the sample, a total of N = 250 medical records corresponding to residents of the nursing home were considered, and a prevalence (P) of 50%, a margin of error (d) of 7.5% and a confidence level of 95% were estimated according to the literature, for an estimated size of n = 101 participants. The EpiInfo programme, version 6 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, United States) was used to calculate sample size.

The study by Mori et al.15 included patients 65 years of age and older who could follow orders. Hence, in our study, 100 participants were selected by means of simple random sampling; they had to be ≥65 years old, have the ability to obey directions and be capable of completing the functional assessment and the assessment of swallowing function. Our study’s initial sample did not include participants with a diagnosis of severe dementia since it was not possible to be sure that these participants could be thoroughly assessed due to their lack of ability to follow orders.

After informed consent was obtained, the questionnaire was processed by the members of the interdisciplinary team at the nursing home, consisting of resident physicians in geriatrics and family medicine and professionals in speech therapy, physiotherapy, nutrition, nursing and psychology. The study protocol was approved by the independent ethics committee of the Hospital Geriátrico Ancianato San Miguel [San Miguel Geriatric Hospital for the Elderly] in Cali, Colombia.

Study variablesOutcomeSarcopenic dysphagia in institutionalised OAs.

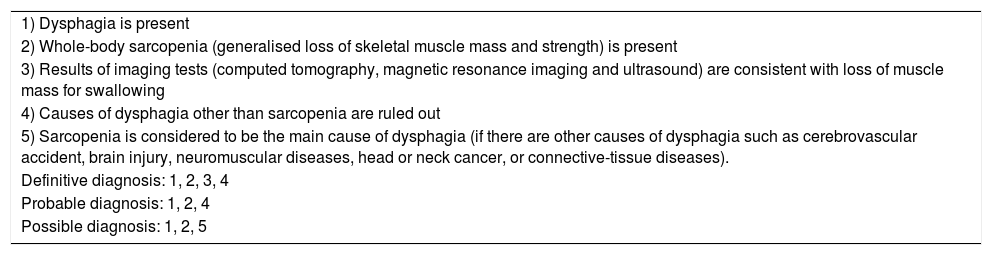

Diagnosis of sarcopenic dysphagiaDysphagia and sarcopenia are criteria required for the diagnosis of sarcopenic dysphagia, but are not sufficient in themselves. Sarcopenia can be caused by conditions such as age, inactivity, undernutrition and diseases including acute and chronic inflammation, as well as neuromuscular diseases; therefore, if they are present, it should be determined whether sarcopenia and not any other possible aetiology is the main cause of dysphagia. Table 1 describes the diagnostic criteria for sarcopenic dysphagia.15

Consensus diagnostic criteria for sarcopenic dysphagia.

| 1) Dysphagia is present |

| 2) Whole-body sarcopenia (generalised loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength) is present |

| 3) Results of imaging tests (computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound) are consistent with loss of muscle mass for swallowing |

| 4) Causes of dysphagia other than sarcopenia are ruled out |

| 5) Sarcopenia is considered to be the main cause of dysphagia (if there are other causes of dysphagia such as cerebrovascular accident, brain injury, neuromuscular diseases, head or neck cancer, or connective-tissue diseases). |

| Definitive diagnosis: 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Probable diagnosis: 1, 2, 4 |

| Possible diagnosis: 1, 2, 5 |

Source: Mori et al.15

In the Mori et al.15 study, the authors proposed an abridged algorithm when no instrument is available to measure tongue strength, which is often the case. This evaluates the presence of sarcopenia and dysphagia. Patients with sarcopenia, abnormal swallowing function and no dysphagia-causing disease can be diagnosed with possible sarcopenic dysphagia without measuring tongue pressure.

The authors evaluated sarcopenia according to the criteria established by the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS), considering grip strength and gait speed.15 Our study adapted these criteria and also included measurement of calf circumference, which is validated in the AWGS consensus2 and was used in the Mori et al. study in cases in which more advanced studies for assessment of body composition such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and bio-electrical impedance analysis (BIA) were not available.

Swallowing function was assessed using the volume-viscosity clinical examination method. This test was performed by a speech pathologist trained in working with OAs. It assesses swallowing efficacy (the patient’s ability to ingest all calories and water needed to be well nourished and hydrated) and swallowing safety (the patient’s risk of respiratory complications). The test uses three different viscosities and three different volumes. It yields information on the safest viscosity and volume for each patient. Its diagnostic sensitivity is 88.1% for swallowing safety abnormalities and 89.8% for swallowing efficacy abnormalities.20 The goal is to identify clinical signs of decreased efficacy, such as inadequate lip seal, oral or pharyngeal residue and piecemeal deglutition (multiple swallows per bolus) as well as clinical signs of decreased safety during swallowing, such as chances in voice quality (including wet voice), cough or a 3% decrease in oxygen saturation, measured with pulse oximetry, to detect silent aspiration.21 This procedure requires the patient to be alert, tolerate sitting up and obey orders. It was designed to protect patients from aspiration, starting with nectar-thick and increasing volumes from 5 ml to 10 ml and 20 ml, with a progression from less difficult to more difficult. When patients completed the nectar-thick series with no symptoms of aspiration (cough or 3% drop in oxygen saturation), a honey-thick series was evaluated, also with volumes of growing difficulty (5 ml–20 ml), and, finally, a pudding-thick series was evaluated in the same way (5 ml–20 ml). One or more signs of abnormal safety or efficacy indicated that the patient had dysphagia.22 We established a classification of degree of dysphagia according to the number of abnormalities in safety and efficacy found in the test:

- 1

Mild dysphagia: 1–2 signs of abnormal efficacy or safety.

- 2

Moderate dysphagia: 3–4 signs of abnormal efficacy or safety.

- 3

Severe dysphagia: 5–6 signs of abnormal efficacy or safety.

Mori et al., as a final point in their abridged algorithm, excluded patients with a disease that was obviously the cause of their dysphagia; however, participants with diseases in whom age, functional capacity, nutrition or sarcopenia was believed to be the cause were not excluded.15

CovariatesSociodemographic data and biological, mental and functional variables were collected. Age, sex and known variables that might affect outcomes were included in the analyses. To assess performance status, the Barthel Index (BI) was used. This index evaluates 10 basic activities of daily living and assigns a predetermined value for autonomy/independence.23 Scores range from 0 to 100; 0 is maximum dependence and 100 is complete independence. The BI was used as a categorical variable (<60, or dependent, versus ≥60, or independent).

Cognitive status was evaluated using the Mini-Mental State Examination.24 The participants were grouped by score as normal (≥24), mild (19–23), moderate (14–18) or severe (<14). Patients with a score of less than 14 were excluded from the study.

With regard to comorbidity, the Charlson Comorbidity Index was used and analysed as a categorical variable. For this index, the median score in this population was established as the cut-off point and two groupings, with comorbidity (0–4) and without comorbidity (>4), were considered.25

To evaluate gait speed, the distance used was three metres and time was measured with a digital stopwatch. Two tests were performed and the better value was taken.

Grip strength was measured using a hand dynamometer (Jamar Hydraulic Hand Dynamometer®, Patterson Medical Ltd., Warrenville, Illinois, United States). All patients underwent the test while standing with their arms at their sides. The test was performed twice and the better value obtained was taken. Cut-off points were established according to the algorithm used by Mori et al.:15 26 kg for men and 18 kg for women.

Calf circumference was evaluated in a seated position with both feet planted firmly on the floor, forming a 90° angle; the measurement was made at the thickest part of the calf, and additional measurements were taken above and below that point to ensure that the first measurement was indeed the largest. A cut-off point of 31 cm was established according to the European consensus definition of sarcopenia.2

To assess nutritional status, the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) screening tool was used. This tool enables assessment of nutritional status and identification of patients at risk of or showing signs of undernutrition. It classifies nutritional status by score: 0–7 points correspond to malnutrition, 8–11 points to risk of malnutrition and 12–14 points to normal nutritional status.26

Statistical analysisExploratory and descriptive analyses were performed. Proportions (%) were estimated for categorical variables. For continuous variables, medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) were used. For the bivariate analysis between the independent variables and the three-category variables (sarcopenic dysphagia, non-sarcopenic dysphagia and other), the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used, depending on the case, for categorical variables, and non-parametric analysis of variance (ANOVA) (the Kruskal–Wallis test) was used for quantitative variables.

Two multivariate logistic regression models were prepared to determine the association between dysphagia and the variables that showed statistical significance in the bivariate analysis, as follows:

- –

Model 1: dichotomous sarcopenic dysphagia dependent variable (1 = sarcopenic dysphagia versus 0 = non-sarcopenic dysphagia or no dysphagia)

- –

Model 2: ordinal sarcopenic dysphagia dependent variable (1 = no dysphagia; 2 = non-sarcopenic dysphagia; 3 = sarcopenic dysphagia).

Thus the ORs with their respective 95% CIs were obtained. All analyses were performed in the SAS statistics software programme, version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, United States); the level of statistical significance selected was p < 0.05 for the two-tailed test.

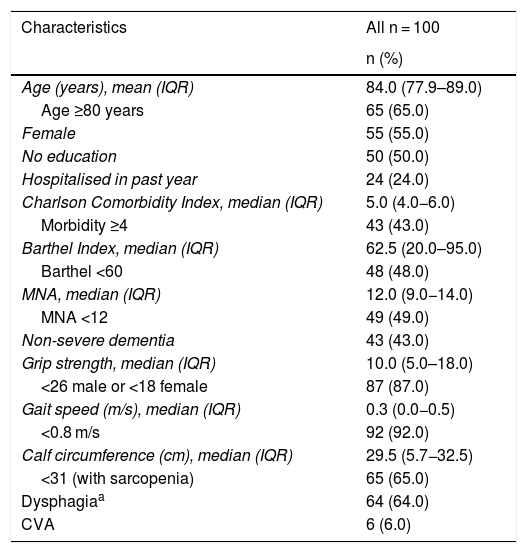

ResultsThe general characteristics of the population are shown in Table 2. The median age was 84 years with an IQR of 77.9–89 years. OAs ≥80 years of age comprised 65% of the population and 55% were women. The median Charlson Comorbidity Index score was 5 points with an IQR of 4–6 points. As for BI scores, the median was 62.5 points with an IQR of 20–95 points. Functional dependence was found in 48%. Regarding nutritional status, the mean MNA score was 12 points with an IQR of 9–14 points; 49% had a score of less than 12. In the evaluation of cognitive function, 43% had any degree of dementia; OAs with severe dementia were excluded.

General characteristics of the population.

| Characteristics | All n = 100 |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Age (years), mean (IQR) | 84.0 (77.9–89.0) |

| Age ≥80 years | 65 (65.0) |

| Female | 55 (55.0) |

| No education | 50 (50.0) |

| Hospitalised in past year | 24 (24.0) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 5.0 (4.0−6.0) |

| Morbidity ≥4 | 43 (43.0) |

| Barthel Index, median (IQR) | 62.5 (20.0–95.0) |

| Barthel <60 | 48 (48.0) |

| MNA, median (IQR) | 12.0 (9.0−14.0) |

| MNA <12 | 49 (49.0) |

| Non-severe dementia | 43 (43.0) |

| Grip strength, median (IQR) | 10.0 (5.0–18.0) |

| <26 male or <18 female | 87 (87.0) |

| Gait speed (m/s), median (IQR) | 0.3 (0.0−0.5) |

| <0.8 m/s | 92 (92.0) |

| Calf circumference (cm), median (IQR) | 29.5 (5.7−32.5) |

| <31 (with sarcopenia) | 65 (65.0) |

| Dysphagiaa | 64 (64.0) |

| CVA | 6 (6.0) |

CVA = history of cerebrovascular accident; IQR: interquartile range.

Grip strength was found to have a median of 10 kg with an IQR of 5−18 kg and decreased grip strength was detected in 87% of the OAs. Concerning gait speed, the median was 0.3 m/s, with an IQR of 0−0.5 m/s, and 92% of the OAs had decreased gait speed. Median calf circumference was 29.5 cm with an IQR of 25.7−32.5 cm, and 65% of the OAs had a circumference <31 cm.

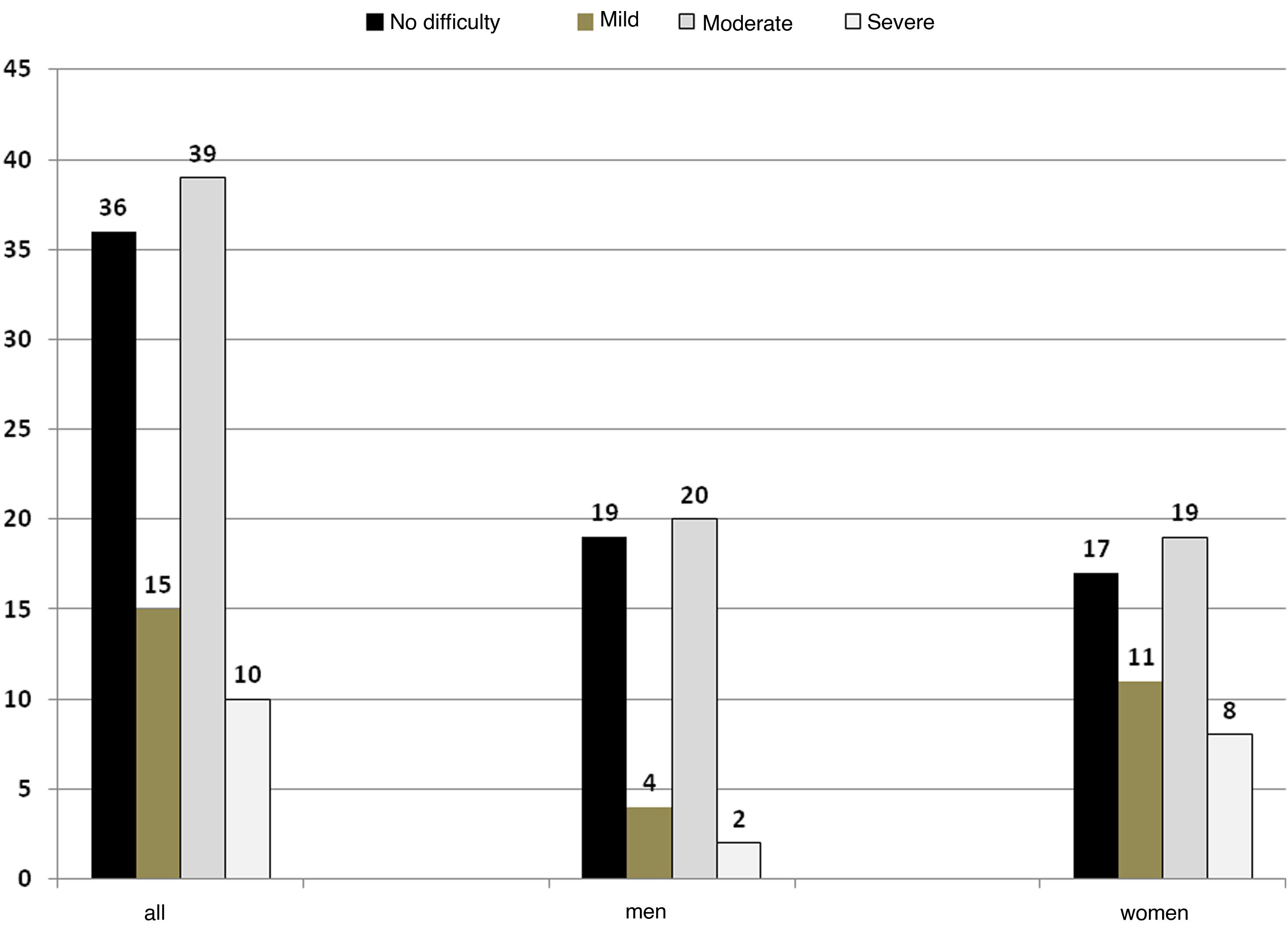

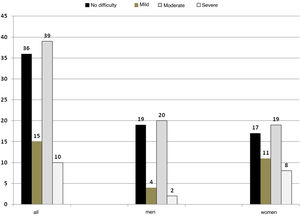

As regards assessment of swallowing function, 64% had some degree of dysphagia; of these, 15% were classified as mild dysphagia, 39% as moderate dysphagia and 10% as severe dysphagia. No difficulty was considered no dysphagia (Fig. 1). There were no significant differences by sex in the categories (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.12).

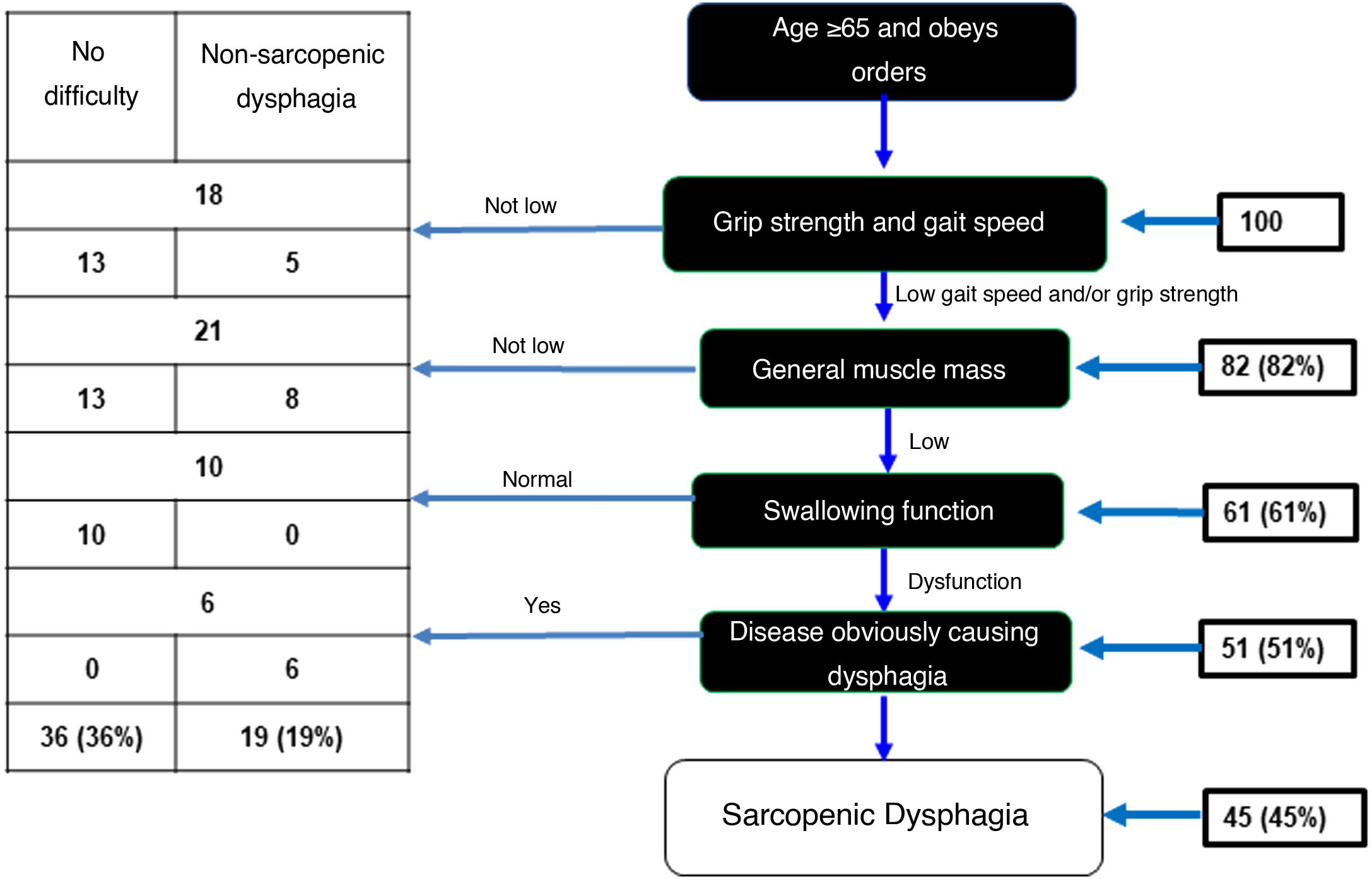

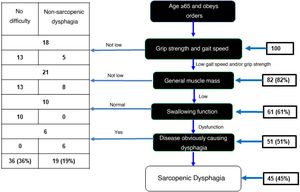

In the sample of 100 OAs, 82 showed low grip strength and gait speed. Of these, 61 OAs had low muscle mass evaluated with calf circumference. Assessment of swallowing function using the volume-viscosity test revealed 51 of these 61 to have dysphagia of any degree. Six of these 51 were excluded because analysis each case was analysed individually and the six were believed to have dysphagia due to a different cause (a history of CVA). As a result, there was a prevalence of sarcopenic dysphagia of 45% (Fig. 2). In addition, 36% were found to have no dysphagia and 19% were found to have non-sarcopenic dysphagia.

Diagnostic algorithm for sarcopenic dysphagia.

Adapted from Mori et al.15

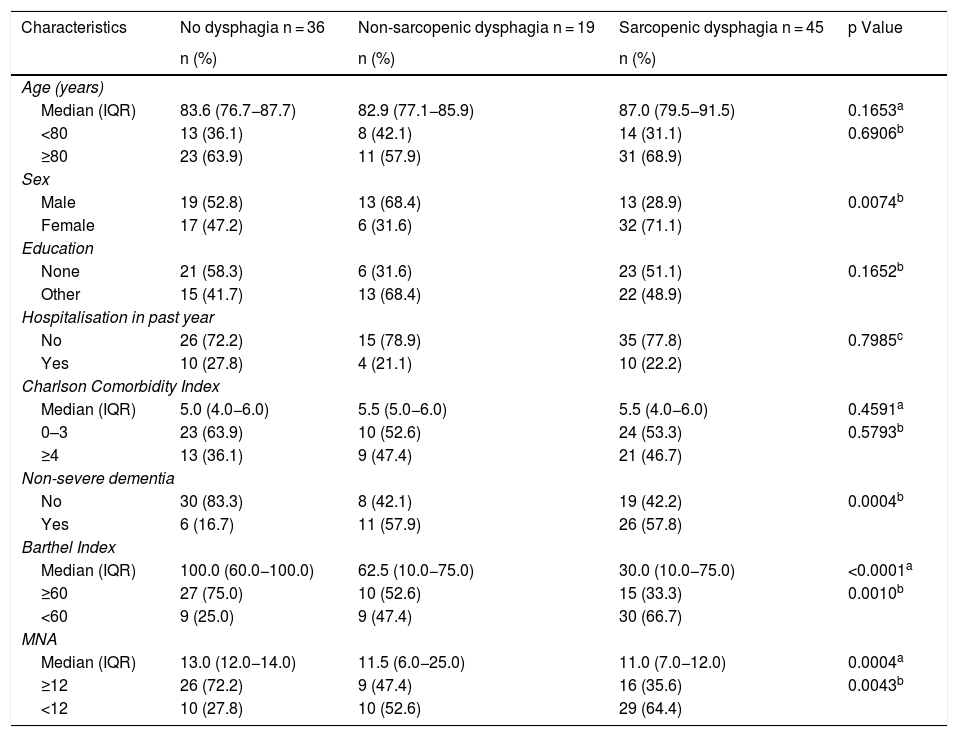

In the bivariate analyses, patients with sarcopenic dysphagia were characterised by being women, having non-severe dementia, having greater physical disability as evaluated by the BI and being at risk of malnutrition (Table 3).

Bivariate analyses according to presence of sarcopenic dysphagia.

| Characteristics | No dysphagia n = 36 | Non-sarcopenic dysphagia n = 19 | Sarcopenic dysphagia n = 45 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 83.6 (76.7−87.7) | 82.9 (77.1−85.9) | 87.0 (79.5−91.5) | 0.1653a |

| <80 | 13 (36.1) | 8 (42.1) | 14 (31.1) | 0.6906b |

| ≥80 | 23 (63.9) | 11 (57.9) | 31 (68.9) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 19 (52.8) | 13 (68.4) | 13 (28.9) | 0.0074b |

| Female | 17 (47.2) | 6 (31.6) | 32 (71.1) | |

| Education | ||||

| None | 21 (58.3) | 6 (31.6) | 23 (51.1) | 0.1652b |

| Other | 15 (41.7) | 13 (68.4) | 22 (48.9) | |

| Hospitalisation in past year | ||||

| No | 26 (72.2) | 15 (78.9) | 35 (77.8) | 0.7985c |

| Yes | 10 (27.8) | 4 (21.1) | 10 (22.2) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 5.0 (4.0−6.0) | 5.5 (5.0−6.0) | 5.5 (4.0−6.0) | 0.4591a |

| 0–3 | 23 (63.9) | 10 (52.6) | 24 (53.3) | 0.5793b |

| ≥4 | 13 (36.1) | 9 (47.4) | 21 (46.7) | |

| Non-severe dementia | ||||

| No | 30 (83.3) | 8 (42.1) | 19 (42.2) | 0.0004b |

| Yes | 6 (16.7) | 11 (57.9) | 26 (57.8) | |

| Barthel Index | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 100.0 (60.0−100.0) | 62.5 (10.0−75.0) | 30.0 (10.0−75.0) | <0.0001a |

| ≥60 | 27 (75.0) | 10 (52.6) | 15 (33.3) | 0.0010b |

| <60 | 9 (25.0) | 9 (47.4) | 30 (66.7) | |

| MNA | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 13.0 (12.0−14.0) | 11.5 (6.0−25.0) | 11.0 (7.0−12.0) | 0.0004a |

| ≥12 | 26 (72.2) | 9 (47.4) | 16 (35.6) | 0.0043b |

| <12 | 10 (27.8) | 10 (52.6) | 29 (64.4) | |

p Values looking for differences in each variable through the three categories (other, non-sarcopenic dysphagia and sarcopenic dysphagia), obtained by non-parametric ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis), chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests.

IQR: interquartile range; MNA: Mini Nutritional Assessment.

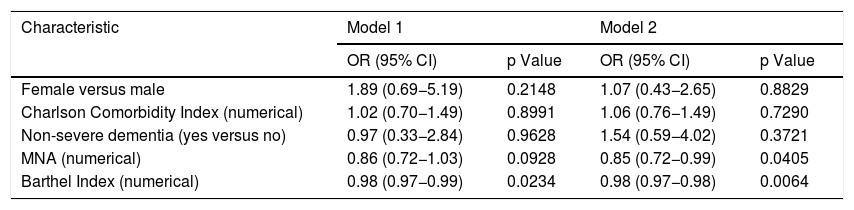

In the multivariate analyses, adjusted logistic regression analyses were performed with the variables that had a p value <0.15 in the bivariate analyses, with the addition of comorbidity, an important condition according to the existing evidence,1 in order to determine the association between independent variables and the dependent variable (sarcopenic dysphagia). Two multivariate logistic regression models were evaluated (Table 4). According to them, for each point scored on the BI, the odds of having sarcopenic dysphagia decrease by 2% (OR = 0.98 [95% CI, 0.97−0.98]). With respect to nutritional status, for each point scored on the MNA, the odds of having sarcopenic dysphagia decrease by 15% (OR = 0.85 [95% CI, 0.72−0.99]).

Multivariate logistic regression, association between sarcopenic dysphagia and other variables (n = 100).

| Characteristic | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Female versus male | 1.89 (0.69−5.19) | 0.2148 | 1.07 (0.43−2.65) | 0.8829 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (numerical) | 1.02 (0.70−1.49) | 0.8991 | 1.06 (0.76−1.49) | 0.7290 |

| Non-severe dementia (yes versus no) | 0.97 (0.33−2.84) | 0.9628 | 1.54 (0.59−4.02) | 0.3721 |

| MNA (numerical) | 0.86 (0.72−1.03) | 0.0928 | 0.85 (0.72−0.99) | 0.0405 |

| Barthel Index (numerical) | 0.98 (0.97−0.99) | 0.0234 | 0.98 (0.97−0.98) | 0.0064 |

Model 1: dichotomous sarcopenic dysphagia dependent variable (1 = sarcopenic dysphagia versus 0 = non-sarcopenic dysphagia or no dysphagia); Model 2: ordinal sarcopenic dysphagia dependent variable (1 = no dysphagia; 2 = non-sarcopenic dysphagia; 3 = sarcopenic dysphagia).

CI: confidence interval; MNA: Mini Nutritional Assessment; OR: odds ratio.

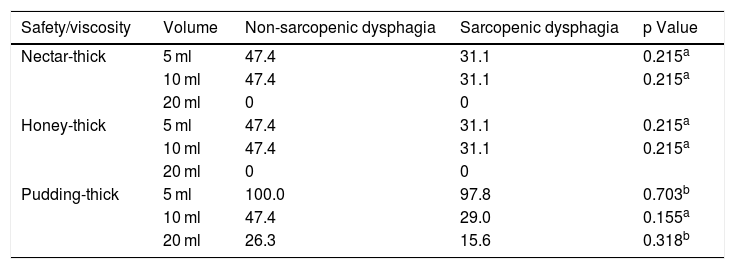

In addition, the type of texture or viscosity tolerated (nectar-thick, honey-thick and pudding-thick) was analysed and there were no significant differences between non-sarcopenic dysphagia and sarcopenic dysphagia (Table 5) or in safety or efficacy. There were also no differences (p = 0.926) in severity of dysphagia between non-sarcopenic dysphagia (mild = 26.3%, moderate = 57.9% and severe = 15.8%) versus sarcopenic dysphagia (mild = 22.2%, moderate = 62.2% and severe = 15.6%).

Percentages (%) of older adults with no swallowing abnormality in tests of safety or efficacy according to condition of sarcopenic or non-sarcopenic dysphagia.

| Safety/viscosity | Volume | Non-sarcopenic dysphagia | Sarcopenic dysphagia | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nectar-thick | 5 ml | 47.4 | 31.1 | 0.215a |

| 10 ml | 47.4 | 31.1 | 0.215a | |

| 20 ml | 0 | 0 | ||

| Honey-thick | 5 ml | 47.4 | 31.1 | 0.215a |

| 10 ml | 47.4 | 31.1 | 0.215a | |

| 20 ml | 0 | 0 | ||

| Pudding-thick | 5 ml | 100.0 | 97.8 | 0.703b |

| 10 ml | 47.4 | 29.0 | 0.155a | |

| 20 ml | 26.3 | 15.6 | 0.318b |

We conducted a study using an abridged diagnostic algorithm previously validated in a population of institutionalised OAs. The strength of the algorithm used is that it enables diagnosis of possible sarcopenic dysphagia without evaluating the muscle mass of the muscles involved in swallowing and without evaluating tongue strength, which is not easy to measure in routine clinical practice as it requires a specialised instrument. Our study yielded two significant findings. First, it determined a prevalence of sarcopenic dysphagia in the institutionalised OA population of 45%. Second, it found that the variables significantly associated with sarcopenic dysphagia were performance status and nutritional status.

The prevalence and prognosis of sarcopenic dysphagia have not yet been clearly documented. In our study, the prevalence found in a population of institutionalised OAs was 45%. This was similar to that found in the original study by Mori et al.,15 who found a prevalence of 41.8% in a population of patients admitted to acute-care hospitals, long-term care homes and rehabilitation facilities.

The multivariate logistic regression analysis in Model 2 showed that the main factors associated with sarcopenic dysphagia were nutritional status evaluated by the MNA and performance status evaluated by the BI. These results were similar to those of a study by Maeda and Akagi,27 which also found an association with malnutrition, dementia and performance status in a population of 95 OAs hospitalised on an acute care unit. There is evidence in the literature that malnutrition contributes to the aetiology of both sarcopenic dysphagia and sarcopenia.28

We found that, in the total sample, 36% had no dysphagia and 19% had non-sarcopenic dysphagia — that is, dysphagia of another aetiology. Six patients had a history of CVA, and when each of their cases was reviewed individually, this history was determined to be the cause of their dysphagia. We also found that 68.9% of the OAs with sarcopenic dysphagia were over 80 years of age; this is biologically plausible as older age increases the likelihood of sarcopenia.2 In addition, we detected a higher rate of sarcopenic dysphagia in women —71% — which was statistically significant (p = 0.0074). These findings were consistent with the Maeda and Akagi27 study, in which 67% of hospitalised OA patients with sarcopenic dysphagia were women.

The bivariate analyses found a rate of 57.9% of non-sarcopenic dysphagia and a rate of 57.8% of sarcopenic dysphagia in OA patients with non-severe dementia. A study by Altman et al.29 yielded a similar finding, reporting a prevalence of 60% of dysphagia in patients with dementia. In these individuals, measurements of muscle strength and physical function are difficult; however, it is important to diagnose sarcopenic dysphagia in this context, because dementia is associated with sarcopenia30,31 and the relationship between dementia and dysphagia is widely known.32

Knowledge and detection of sarcopenic dysphagia matter, because failure to diagnose this condition increases risks of complications and adverse events.18 It appears to be more severe than other types of dysphagia, and there is evidence that treatment focused on nutritional support and strength training of the muscles involved in swallowing are linked to good outcomes. Maeda and Akagi33 reported the case of an 80-year-old woman who recovered from sarcopenic dysphagia with aggressive nutritional management and physical therapy, achieving increased body weight and improved swallowing function; even six months after the intervention, she maintained her improvement in swallowing function as evaluated by videofluoroscopy. Wakabayashi and Sakuma28 suggested a strategy called rehabilitation nutrition for patients with sarcopenia in whom nutritional supplementation is provided according to exercise load, daily activity and nutritional status. Nevertheless, more research is needed to improve understanding of sarcopenic dysphagia and its treatment.

We also found that the prevalence of some degree of dysphagia among institutionalised OAs was 64%, consistent with the literature. In a study conducted by Lin et al.5 in Taiwan, which included 1221 institutionalised OAs, the general prevalence of dysphagia was 51%. Another study, conducted by Ferrero López et al. at five geriatric institutions in Spain and including 422 OAs, found a prevalence of dysphagia of 65%.8

Another of our findings was that impairment of muscle strength was prevalent in institutionalised OAs. According to the consensus of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP), nine out of every 10 OAs have decreased grip strength and gait speed;8 similarly, in our study, average grip strength was 10 kg (5.0−18.0 kg) and was decreased in 87% of the OAs (Table 2).

Low muscle mass has been established as a possible risk factor for dysphagia. Some studies have identified body mass index as the most predictive factor for dysphagia.34 In our study, the prevalence of sarcopenia was higher (61%), in contrast to the reports in the literature, as in a recently published meta-analysis conducted by Shen et al., in which the prevalence was 41% in institutionalised OAs.35

The strengths of the study include the fact that swallowing was assessed using the volume-viscosity clinical examination method performed by a speech pathologist with training and expertise in caring for the OA population, conferring internal validity on the results. In addition, it was a pioneering study on this subject on a national level in Colombia, as its target population was institutionalised OAs, who are known to have a high prevalence of dysphagia, such that its early diagnosis and treatment have a significant impact on their health.

A limitation of our study is that it did not include objective measurement of tongue strength, which requires a specialised instrument. However, it did use the diagnostic algorithm proposed and validated by Mori et al., which carries the advantage of being applicable in daily clinical practice with no need to use the tongue strength variable for diagnosis. Another limitation is that patients with severe dementia were not included, which might have introduced selection bias into our study.

In conclusion, sarcopenic dysphagia has a high prevalence in institutionalised OAs, and the variables independently associated with it were functional dependence and poor nutritional status.

The results of our study led us to raise the possibility of conducting a future multicentre cohort study evaluating adverse outcomes such as mortality, pneumonia and nutritional and functional decline.

FundingThis research has not received specific funding from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Moncayo-Hernández BA, Herrera-Guerrero JA, Vinazco S, Ocampo-Chaparro JM, Reyes-Ortiz CA. Disfagia sarcopénica en adultos mayores institucionalizados. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:602–611.