In the current context of limited economic and health resources, efficiency of drug treatments is of paramount importance, and their clinical effects and related direct costs should therefore be analyzed. Liraglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) which, in addition to its normoglycemic effects, induces a significant improvement in body weight and several cardiovascular risk factors. The aim of this narrative review is to summarize the available evidence about the effects of liraglutide upon cardiovascular risk factors and how these improve its cost-effectiveness profile. Despite the relatively higher cost of liraglutide as compared to other alternative therapies, liraglutide has been shown to be cost-effective when clinical indicators and total costs associated to T2DM management are analyzed.

En el contexto actual de recursos económicos y sanitarios limitados tiene una gran importancia la eficiencia de los tratamientos farmacológicos, analizando sus efectos clínicos y sus costes directos asociados. La liraglutida es un agonista del receptor del péptido de tipo 1 similar al glucagón (GLP-1) aprobada para el tratamiento de la diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2), que además de su acción normoglucemiante induce mejorías significativas en el peso corporal y sobre diversos factores de riesgo cardiovascular. El objetivo de esta revisión breve es resumir la evidencia disponible acerca de los efectos de la liraglutida sobre los factores de riesgo cardiovascular y cómo estos mejoran su perfil de coste-efectividad. A pesar de su coste farmacológico, relativamente superior al de otras alternativas terapéuticas, la liraglutida ha demostrado ser coste-efectiva cuando se analizan los indicadores clínicos y los costes totales asociados al abordaje de la DM2.

The recently published di@betes study showed a high prevalence of diabetes in Spain, affecting 13.8% of the population.1 This increase as compared to prior estimates is associated with increased morbidity and mortality rates which represent a significant financial burden for health systems due to the increase in associated direct medical costs. On the other hand, in the current context of limited financial and healthcare resources, it has become even more important not only to prevent complications of diabetes because of their attendant financial burden, but also to assess the efficiency of drug treatments by analyzing both their direct and indirect medical costs. In addition, 50% of the total cost incurred by diabetes is associated with cardiovascular complications,2 and some reflection is therefore needed regarding the suitability of current antidiabetic treatments, not only with regard to blood glucose control, but also in terms of joint assessment of the effects on other factors that determine their cost, such as effects on body weight, systolic blood pressure (SBP), lipids, and the attendant risk of hypoglycemia.

Liraglutide is a recombinant glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist which, in addition to its hypoglycemic effect, has a positive impact on body weight and different cardiovascular risk factors such as blood pressure and lipid parameters.3 Liraglutide has an antidiabetic potency similar to basal insulin,4 and its additional advantages include its virtually nil risk of hypoglycemia and its ability to induce weight loss.3 The most common adverse reactions of liraglutide include gastrointestinal complications, mainly nausea, which usually occur in the first weeks after the start of treatment and are generally mild and transient in nature.5 The main factor limiting the potential benefits of liraglutide in particular, and the class of GLP-1 receptor agonists in general include their higher cost as compared to other treatment options. There are however consistent data, and the results of evaluations by international bodies, which show that drugs in this therapeutic class may decrease the final cost of treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) as compared to other drugs.6,7

Effects on cost of treatmentDrug costs versus total cost of treatmentAccording to the Cost of Diabetes in a Europe study (CODE-2), the mean direct cost of diabetes in 1999 was €1305 per patient and year, of which 42% was due to pharmacy expenses, 32% to hospitalization expenses, and 26% to outpatient costs.8 Regarding pharmacy expenses, 4.6% represented expenditure on oral hypoglycemic agents, 4.7% on insulins, 14% on drugs for cardiovascular conditions, and 0.6% on glucose test strips. According to this study, most costs associated with patients with diabetes were expenses derived from hospitalization and the treatment of comorbidities, while the costs of antidiabetic treatment (oral drugs and insulins) accounted for less than 10%. Recent data on the cost of diabetes in Spain are available. In a study conducted in Catalonia in 2011, the mean estimated annual cost per diabetic patient was €3362.8, as compared to €2156.5 per non-diabetic patient (an absolute difference of €1206.3, a 59.9% relative increase).9 Absolute differences of €340.2 (a 38.4% increase) for the mean annual cost of hospitalizations and of €435.8 (an 89% increase) for pharmaceutical costs were reported.9 Recently, data reported in two national8,10 and two regional studies11,12 were used to estimate the annual costs associated with T2DM in Spain in 2009: the direct annual cost per patient was €1660, the annual cost of productivity losses was €916, and the annual direct cost of microvascular and macrovascular complications was €2930, of which 40.2% was due to hospitalization, 38.5% to drug treatment, and 21.3% to outpatient monitoring, respectively.13

Effects on healthcare costs associated with hypoglycemiaThe general metabolic control goal defined by current recommendations for T2DM is a glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) value of 7% or less.14 The control goal may be more ambitious (HbA1c<6.5%) in young patients with a short duration of diabetes and no microvascular or macrovascular complications, and provided the goal is achieved with no increase in hypoglycemic episodes.14 By contrast, higher HbA1c values (7.5–8%) are considered adequate in elderly patients, with cardiovascular disease or chronic complications of already established diabetes.14 However, and despite the wide dissemination of these recommendations, a high proportion of patients do not achieve these control goals. Thus, it is estimated that 45% of Spanish patients with T2DM on non-insulin treatment have an HbA1c level higher than 7%.15 Low adherence to hygienic and dietary measures16 and an increased risk of hypoglycemia when treatment for diabetes is intensified17 represent the main limiting factors to the achievement of optimum control. The therapeutic inertia of healthcare professionals, which may delay the start of treatment intensification, also contributes to this situation.18

In this context, the availability of treatments with a potent hypoglycemic effect but a low risk of hypoglycemia may help in achieving adequate metabolic control in a greater number of patients, with a positive impact on the future risk of microvascular complications and, possibly, macrovascular complications also.19 In the clinical trial program Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes (LEAD), liraglutide, in different treatment combinations, induced a change in HbA1c ranging from 0.2% to 1.3%, with a low hypoglycemia rate (0.03–1.9 episodes per patient and year).3

In addition to promoting adequate metabolic control, the use of drugs involving less risk of hypoglycemia may also decrease the direct costs derived from this complication. As regards the direct costs of hypoglycemia, the greatest expense is associated with severe hypoglycemic episodes, according to data published in 2004 (€3597).20 Mild hypoglycemic episodes have a lower economic impact, but because of their greater frequency they also have a significant impact resulting from changes of medication, the increased use of glucose test strips, increased nurse visits, greater need for health education, and increased work absenteeism. The mean estimated cost of mild hypoglycemia ranges from €30 to €35.20 Increased attention to treatments that reduce mild hypoglycemia could therefore have a positive impact on healthcare costs.

Impact on use of glucose test stripsIn its 2010 recommendations on capillary blood glucose self-monitoring (CBGSM),21 the Spanish Society of Diabetes stated that patients with T2DM managed with diet or oral antidiabetic treatment do not need CBGSM, except for those with unstable control, who should perform one control daily or a six-point profile weekly. In patients treated with drugs associated with a risk of hypoglycemia, such as sulfonylureas, weekly monitoring (once daily monitoring or a six-point profile weekly in the event of unstable control) is recommended. Patients treated with basal insulin should perform three tests weekly if they are on stable glucose control, and two or three daily tests otherwise. According to these recommendations, the use of GLP-1 agonists represents savings in costs related to the use of test strips by requiring a lower frequency of self-monitoring, so obviating the need for the three test strips weekly associated with treatment with basal insulin, or the use of one test strip weekly when sulfonylureas are administered.

Other side effects of liraglutideThe adverse reactions most commonly associated with liraglutide are gastrointestinal in nature. Nausea and diarrhea are the most frequent gastrointestinal adverse reactions, followed by vomiting, constipation, abdominal pain, and dyspepsia, which occur less commonly. These reactions occur at the start of treatment with liraglutide and usually decrease within a few weeks. Severe adverse reactions are uncommon. The incidence of acute pancreatitis reported in clinical trials is low, less than 0.2%, and a causal relationship between liraglutide treatment and pancreatic episodes has not yet been established.5,22

Effects on the use of drugs in conditions associated with diabetesGLP-1 agonists have a beneficial effect on different cardiovascular risk factors, including lipid parameters, blood pressure, and weight, in addition to other risk markers such as C reactive protein and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1.3 The effect is included in pharmacoeconomic studies which assess the efficiency of these treatments, and is partly responsible for their positive cost-effectiveness, despite their relatively higher price as compared to other drugs. The greatest expense in the whole treatment of T2DM is related to drugs for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia and high blood pressure,8,23 so that the use of antidiabetic agents with positive effects on blood pressure and lipids may contribute to savings in this field. Treatment with liraglutide was shown to consistently induce a decrease in SBP ranging from 2.1 to 6.7mmHg during the LEAD 1–5 studies.4,15–19,24–27 A recent meta-analysis28 assessed the effects of GLP-1 agonists on blood pressure. In patients treated with liraglutide 1.2mg, an SBP reduction was seen as compared to the placebo (−5.6mmHg; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], −5.85 to −5.36; p<0.001) and glimepiride groups (−2.38mmHg; 95% CI, −4.75 to −0.01; p=0.05). In the group treated with liraglutide 1.8mg, a significant decrease in SBP was also found as compared to the placebo (−4.49mmHg; 95% CI, −4.73 to −4.26; p<0.001) and glimepiride groups (−2.62mmHg; 95% CI, −2.91 to −2.33; p<0.001).

This effect on blood pressure was similar to that achieved by some antihypertensive drugs.29 Thus, it was shown, although in longer studies, that an SBP decrease by 5.6mmHg in patients with DM was associated with a 9% reduction in the risk of microvascular and macrovascular events and to an 18% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular death.30 As regards the effects on lipid profile, decreased triglycerides (28–36mg/dL) were seen during liraglutide treatment, and in some, but not all studies, LDL cholesterol decreased by 9–11mg/dL.27,31

Visits for education/treatment adjustmentsAn additional potential advantage of GLP-1 agonists is decreased healthcare resource utilization related to visits to healthcare professionals. When treatment with basal insulin is started, the initial dose should be adjusted based on blood glucose, and although patient self-adjustment regimens have been shown to be safe and effective,32 patients often do not understand these indications or do not adequately increase insulin dose, and therefore require frequent medical and/or nursing visits. Because of their virtually nil risk of hypoglycemia and because they require no dose adjustment based on blood glucose levels, treatment with GLP-1 agonists should result in a decreased number of visits.

Economic evaluationCost-effectiveness analysisIn the context of limited healthcare resources, both healthcare professionals and authorities increasingly demand economic evaluations of therapeutic and pharmacological actions to optimize these resources. This justifies the incorporation of economic criteria when decisions involving the use of drugs are being taken.

For decades, the therapeutic potential of new drugs has been established based on the efficacy and safety results found in clinical trials. However, the inherent limitations of clinical trials have forced the effectiveness of drugs in standard clinical practice as assessed by observational studies to be taken into account.

Cost-effectiveness analysis of liraglutide in patients with T2DM has been performed using IMS CORE, a computer model simulating disease which was developed to project long-term health outcomes and to estimate the economic consequences of interventions.33 This model is a non-product specific, validated analytical tool that provides real time simulations which take into account treatments of diabetes, strategies for the screening and treatment of macrovascular and microvascular complications, treatment strategies for complications in advanced stages, and multifactorial interventions. Treatment algorithms are specific for the type of diabetes, and take into account therapeutic failures and/or associated adverse effects, and are completely modifiable to account for local treatment patterns. This model allows the incidence of complications, quality-adjusted life years (QALY), and the total costs of interventions to be calculated. In most cost-effectiveness studies published in Spain, the authors recommend the adoption of an intervention when the ratio is below €30,000 per QALY.34

A recent study sponsored by the manufacturer of liraglutide assessed the cost-utility of the drug as compared to sulfonylurea or sitagliptin, which is added to metformin in patients with T2DM.7 The results showed liraglutide to be a cost/effective treatment, as the ratios obtained, £9449/QALY and £16,501/QALY for the 1.2 and 1.8mg doses respectively versus glimepiride, and £9851/QALY (1.2mg) and £10,465/QALY (1.8mg) for similar doses versus sitagliptin, were lower than the decision thresholds established by the evaluation agencies to consider an intervention cost-effective (€30,000/QALY). This cost/effectiveness ratio is similar to that found for treatment with statins in primary (£5400–13,300) and secondary (£3800–13,300) prevention.35

Liraglutide was positively evaluated by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in Great Britain using the CORE model.36 Based on data from LEAD studies and study 1860 (liraglutide versus sitagliptin), the NICE Appraisal Committee concluded that liraglutide was effective in terms of blood glucose control and was associated with beneficial effects on body weight as compared to other agents. Moreover, the ICER for liraglutide versus exenatide in triple therapy was the most robust according to the committee, with a value of £10,000 per QALY gained. The NICE recommends the use of liraglutide to treat patients with T2DM, particularly those who have used up the first treatment step (based on two oral antidiabetic drugs) with weight problems or in whom weight reduction is recommended, or patients who do not benefit from treatment with two oral antidiabetic drugs or with thiazolidinediones and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors.

Patient reported outcomesCurrent guidelines for the treatment of diabetes recommend that antidiabetic drugs should be selected based not only on their efficacy, but also on patient characteristics and preferences.14 Different studies have assessed patient satisfaction with liraglutide treatment. Overall, patients prefer this treatment to other alternatives because they perceive it as a therapeutic option with a low risk of hypoglycemia, a greater normoglycemic effect and a positive effect on weight. Thus, Hermansen et al.37 reported better satisfaction indices in patients treated with liraglutide as compared to metformin. Similarly, in patients with T2DM inadequately controlled with metformin to whom liraglutide (1.2 or 1.8mg/day) or sitagliptin (100mg/day) were added, patients given liraglutide perceived it as a treatment inducing greater hyperglycemia control, and it was therefore the treatment of choice of these patients.38 An additional study evaluating the willingness of patients to pay for a number of attributes of current treatments for diabetes showed that patients were willing to assume some additional cost to achieve weight loss, to decrease or prevent hypoglycemic episodes, and to achieve a greater HbA1c reduction.39

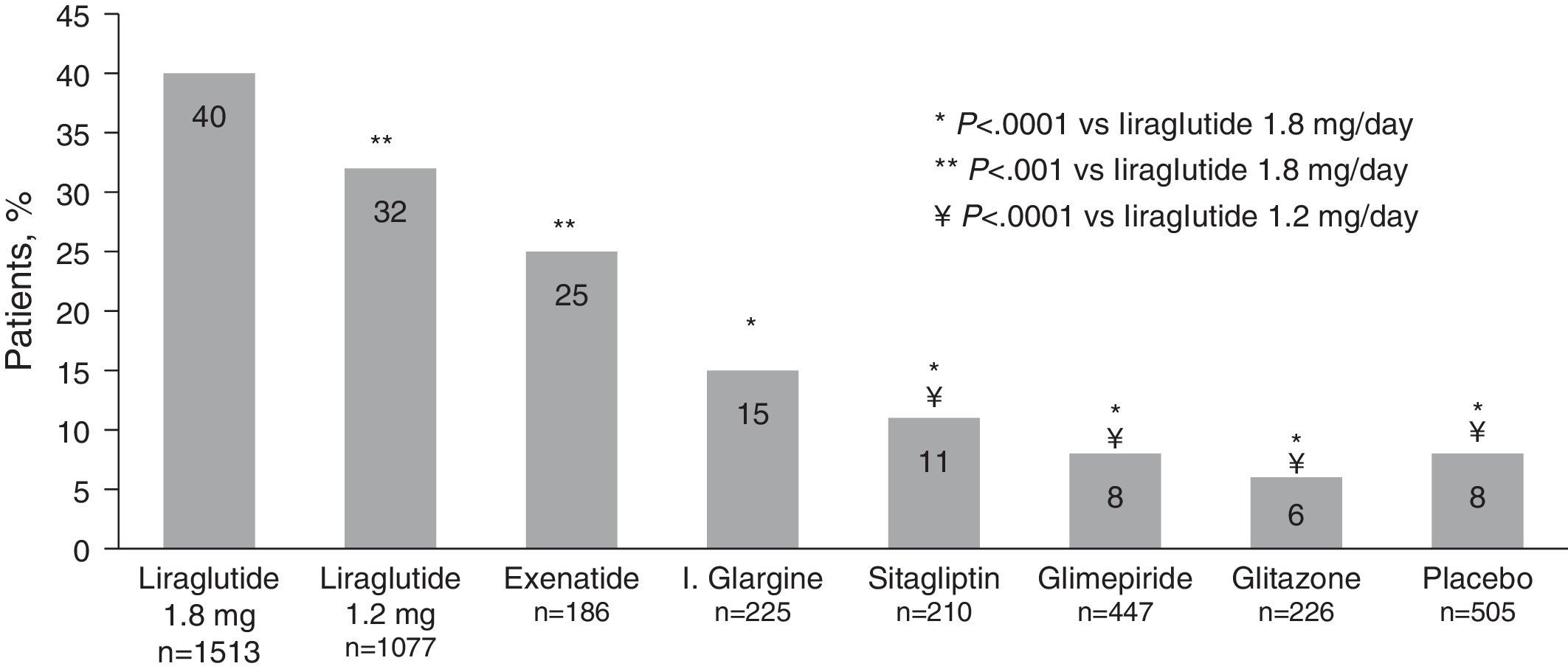

Costs involved in diabetes controlThe “costs of controlling diabetes” methodology allows the cost of treatments to be related to the combined efficacy of the three relevant indicators of diabetes control (blood glucose control, weight neutrality, and the absence of hypoglycemia). Thus, an analysis is made of the cost of taking patients to the control goals including, in addition to blood glucose control (HbA1c<%), two parameters established in the standards of medical care of diabetes of the American Diabetes Association (ADA),32,40 i.e. the risk of both mild and moderate hypoglycemia and the risk of weight increase. In this regard, a recent meta-analysis41 of LEAD studies and the liraglutide versus sitagliptin trial (1860) showed that, after 26 weeks of treatment, 40% of patients treated with liraglutide 1.8mg, and 32% of those given liraglutide 1.2mg achieved the composite endpoint of HbA1c less than 7% with no weight increase or hypoglycemia, as compared to 6%-25% of patients with the comparators (6% rosiglitazone, 8% glimepiride, 15% glargine, 25% exenatide, 11% sitagliptin, and 8% placebo) (Fig. 1).

Proportion of patients achieving the composite endpoint of HbA1c<7% with no hypoglycemia and weight increase.

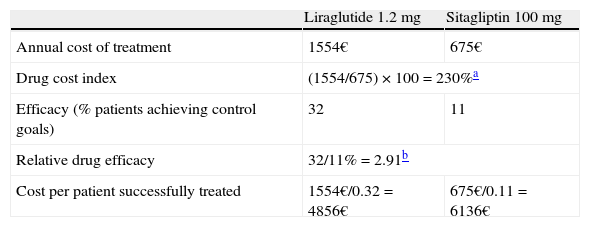

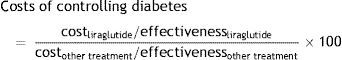

The “costs of controlling diabetes” are expressed through an index that compares the cost/effectiveness ratio of liraglutide and the different treatments used as active comparators in the clinical trials of the LEAD program and the 1860 trial using the following formula:

A value of 100 indicates the equal efficiency of liraglutide and the treatment to which it is compared in terms of efficiency. If the index is below 100, this means that the comparator requires a higher relative cost to achieve the same health outcomes as those achieved with liraglutide, and that the comparator is therefore less cost-effective. By contrast, if the treatment to which liraglutide is compared has an index higher than 100, it shows a greater relative efficiency than treatment with liraglutide. If we apply this to data from the LEAD program and trial 1860, it may be seen that the use of liraglutide is more cost-effective than the use of sitagliptin for achieving the same health outcomes (combined control of all three clinical indicators). That is to say, drug cost per controlled patient associated with liraglutide (€4856) is lower than that of sitagliptin (€6136) (Table 1).42Costs of controlling diabetes with liraglutide as compared to sitagliptin.

| Liraglutide 1.2mg | Sitagliptin 100mg | |

| Annual cost of treatment | 1554€ | 675€ |

| Drug cost index | (1554/675)×100=230%a | |

| Efficacy (% patients achieving control goals) | 32 | 11 |

| Relative drug efficacy | 32/11%=2.91b | |

| Cost per patient successfully treated | 1554€/0.32=4856€ | 675€/0.11=6136€ |

Note: Calculations based on retail selling price, with a 7.5% discount according to Royal Decree-Law 8/2010.

Based on the foregoing, we may conclude that the pharmacoeconomic analysis of therapeutic interventions in diabetes is important for ensuring adequate evaluation of their costs and clinical benefits. In 2009 the NICE recommended,36 on the basis of cost-effectiveness criteria, the use of liraglutide in patients who had exhausted the possibilities of treatment with first-line therapies and in whom weight reduction was also recommended. This evaluation analyzed total costs (pharmacological and medical) and global clinical benefits (including the microvascular and macrovascular complications associated with diabetes) based on different time horizons and in relation to the relevant comparators. The positive performance of liraglutide in terms of cost-effectiveness is also seen when diabetes is considered from a multifactorial approach. Thus, the simultaneous control of all three relevant indicators of diabetes control (HbA1c<7%, weight neutrality, and the absence of hypoglycemia) is achieved with liraglutide at lower drug costs per patient and year as compared to sitagliptin in T2DM.

Conflicts of interestDr. Pedro Mezquita Raya declares the following conflicts of interest: sponsored papers (Bristol Myers Squibb, Astra Zeneca, Esteve, FAES, GSK, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Sanofi-Aventis); consulting work (Bristol Myers Squibb, Astra Zeneca, FAES, NovoNordisk); and research projects (Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lilly, MSD, NovoNordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Tolerx-GSK).

Dr. Rebeca Reyes García declares the following conflicts of interest: sponsored papers (Esteve, FAES, GSK, NovoNordisk, Sanofi-Aventis); and research projects (Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, NovoNordisk, Roche, Tolerx-GSK).

Please cite this article as: Mezquita Raya P, Reyes García R. ¿Es eficiente el tratamiento con liraglutida? Endocrinol Nutr. 2014;61:202–208.