Human intestinal spirochetosis (HIE) is a poorly studied clinical entity with variable clinical manifestations. However, in recent years it has gained special relevance because an increasing number of cases have been described in people living with HIV (PWH) and in patients with a history of sexually transmitted infections (STI) or immunosuppression.

MethodsRetrospective review of all HIE cases identified in a tertiary level hospital (Hospital Universitario la Paz, Madrid) between 2014 and 2021.

Results36 Cases of HIE were identified. Most cases corresponded to males (94%) with a median age of 45 years. 10 patients (29.4%) were PWH and 20 (56%) were men who had sex with men. Although the clinical manifestations were very heterogeneous, the most frequent was chronic diarrhea (47%), and up to 25% of the subjects had clinical proctitis. 39% percent of patients had been diagnosed with an STI in the previous two years, this characteristic being more frequent in PWH (90% vs. 28%; p < 0.01) than in patients without HIV infection. The STI most frequently associated with a diagnosis of HIE was syphilis (31%).

ConclusionHIE is frequently diagnosed with other STIs and affects mostly men who have sex with men, which supports that this entity could be considered as a new STI.

La espiroquetosis intestinal humana (EIH) es una entidad clínica poco estudiada. No obstante, en los últimos años está cobrando una especial relevancia dado que se han descrito un número creciente de casos en personas que viven con VIH (PVIH) y en pacientes con historia de infecciones de transmisión sexual (ITS) o inmunosupresión.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo de todos los casos identificados de EIH en un hospital de tercer nivel (Hospital Universitario la Paz, Madrid) entre los años 2014–2021.

ResultadosSe identificaron 36 casos de EIH, la mayoría en varones (94%) y con una mediana de edad de 45 años. 10 pacientes eran PVIH (29,4%) y 20 (56%) eran hombres que mantenían sexo con hombres. Si bien las manifestaciones clínicas fueron muy heterogéneas, la más frecuente fue la diarrea crónica (47%), y un 25% tuvieron clínica de proctitis. El 39% de los pacientes fueron diagnosticados de una ITS en los dos años previos, siendo este hecho más frecuente en PVIH (90% vs. 28%; p < 0,01) que en pacientes sin infección por VIH. La ITS más frecuentemente asociada al diagnóstico de EIH fue la sífilis (31%).

ConclusiónLa EIH se diagnostica frecuentemente con otras ITS y afecta mayoritariamente a hombres que tienen sexo con hombres, lo cual apoyaría que esta entidad pudiera considerarse como una nueva ITS.

Human intestinal spirochetosis (HIS) is a clinical entity defined by invasion of the large intestine by spirochetes of the genus Brachyspira spp. (B. aalborgi and B. pilosicoli).1 These are slow-growing (three to five days) anaerobic Gram-negative bacilli. The first cases were described in animals such as dogs, pigs or birds, so this entity is considered a zoonosis.2,3 Human involvement was first described in 19822 and currently evidence points to faecal-oral transmission mechanisms, often associated with the consumption of contaminated water, childhood and low socioeconomic status.4

Its pathogenic role is the subject of debate, since a large number of cases are asymptomatic, with gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, proctitis or chronic diarrhoea) being the most common.5–7 Most cases with accompanying symptoms improve with metronidazole antibiotic therapy.6 The manifestations described are heterogeneous, and HIS has even been linked to the development of irritable bowel syndrome8 and, exceptionally, cases of spirochaetemia have been described in immunosuppressed patients.9

Given the absence of characteristic signs or symptoms and the low level of suspicion, diagnosis is usually an incidental pathological finding or a finding in the context of the study of chronic diarrhoea. There are no characteristic gross findings, and spirochetes are identified on the surface of enterocytes with routine staining (haematoxylin and eosin and Warthin-Starry). Suggestive histological data include a decrease in microvilli, which causes a characteristic false brush border2 and a predominantly eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate.10,11 The availability of new immunohistochemical techniques have now made it possible to optimise diagnostic capability for this entity in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, although their use is not standardised.12 At the microbiological level, the presence of these bacteria can be identified by stool polymerase chain reaction.

In recent years, an increasing number of cases have been described in people living with HIV infection (PLHIV) or in men who have sex with men,13–15 which has led to this entity being positioned as a possible sexually transmitted infection (STI).16 Cases have also been reported in patients with immunosuppression or systemic inflammatory diseases.9 The state of immune dysregulation in these patients could promote intestinal colonisation of spirochetes, and in certain situations cause disease through a mechanism other than the sexual route.17,18

In accordance with the limited number of published studies on HIS, we proposed a retrospective review of all those cases diagnosed in our centre in recent years. The main objective of our study was to describe the clinical, epidemiological and pathological characteristics of patients with HIS diagnosed in our centre. The secondary objective was to analyse the possible differences between the PLHIV participants and the other patients.

Patients and methodsThis was a retrospective study reviewing the medical records of all patients who were diagnosed with intestinal spirochetosis at the Hospital Universitario La Paz [La Paz University Hospital] between 2014 and 2021. A search of the records was carried out for intestinal biopsies in the Pathology Department with the diagnosis of intestinal spirochetosis, and in the Microbiology Department database for a positive stool polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for B. pilosicoli or B. aalborgi. This was an in-house semi-nested PCR conducted at the Centro Nacional de Microbiología [National Microbiology Centre] with generic primers against the NADPH oxidase (NOX gene) target for Brachyspira spp.19 Both the hospital electronic databases (HCIS®) and primary care records in the HORUS® integrated platform were reviewed and demographic variables (gender, race, age), clinical variables (associated clinical manifestations, previous diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease or systemic autoimmune disease, history of STIs in the two years prior to diagnosis of HIS, type of sexual intercourse, previous diagnosis of HIV infection), diagnostic variables (gross lesions and their location on colonoscopy, microscopic findings in the biopsy and pathology techniques used, stool PCR results if available) and therapeutic variables (regimen used and its efficacy) were recorded. Clinical episodes up to three months after diagnosis were also reviewed to study cases of new symptom development in untreated patients or disease recurrence in patients who did receive treatment.

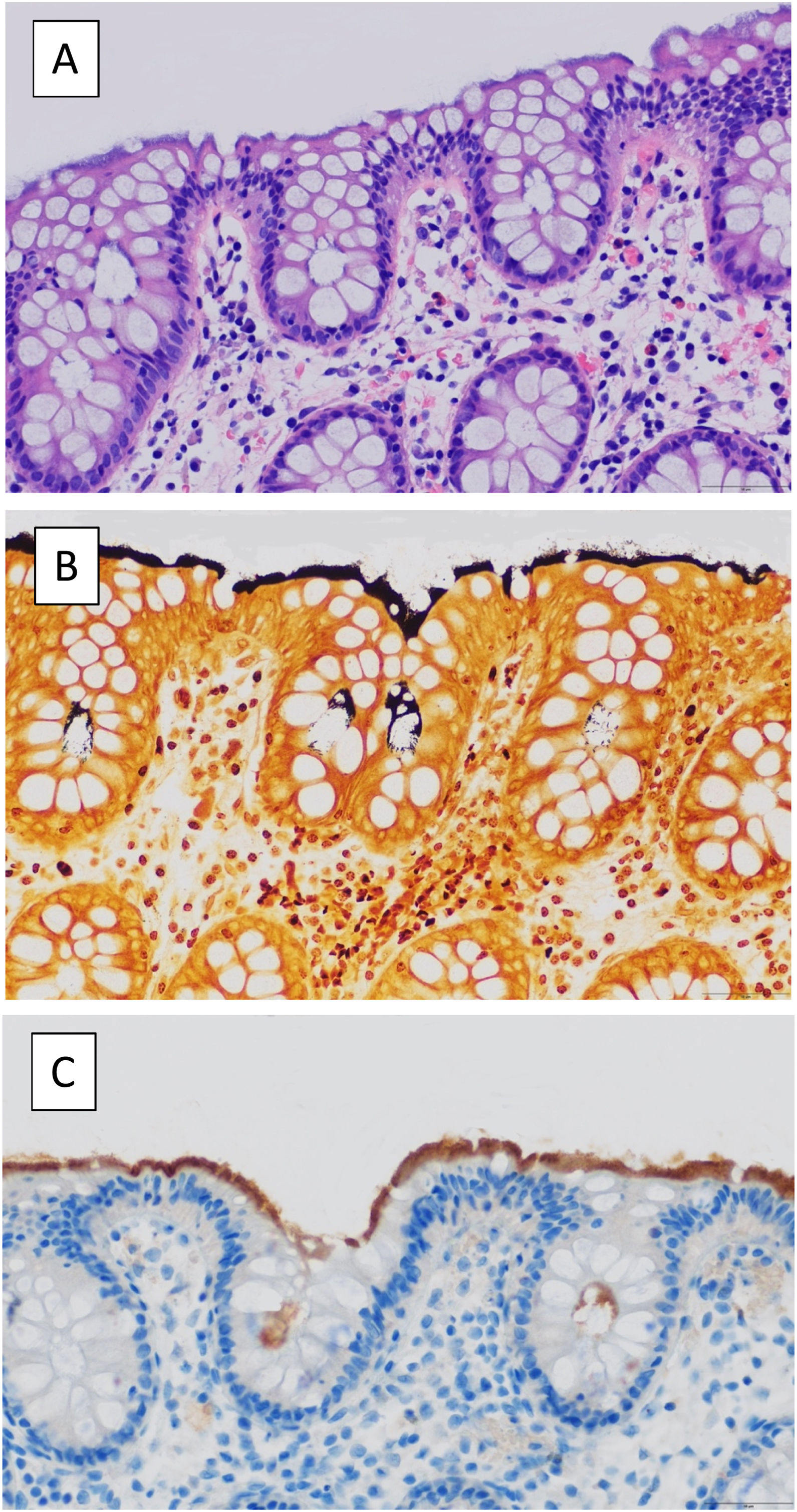

The samples sent to pathology came from biopsies from areas with gross involvement, or otherwise from biopsies from "patchy" intestinal tissue within the chronic diarrhoea study protocol. The definitive diagnosis was reached on observation of a basophilic band of filamentous structures in the brush border with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and, in the event of diagnostic uncertainty, with specific Warthin-Starry staining and/or immunohistochemistry for treponema (Fig. 1). Samples were not systematically sent to the Microbiology Department for study, but only in selected cases in which the clinician considered it relevant to expand the study.

(A) H&E-stained colonic section revealing a basophilic band of filamentous structures at the luminal epithelial border. (B) Spirochetes stained intensely with Warthin-Starry stain. (C) Immunostaining for the spirochete, Treponema pallidum, cross-reacts with the spirochetes of intestinal spirochetosis.

The qualitative variables are presented as absolute number and percentage, and the quantitative variables with the median and interquartile range (IQR = P25–P75).

Comparisons between qualitative variables were made with the Pearson χ2 statistical test and Fisher's exact test as appropriate.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Hospital la Paz independent ethics committee (PI-5009, Minutes 23/2021). An exemption from obtaining informed consent was granted from this committee as the data was obtained retrospectively.

ResultsDemographic and clinical dataWe identified a total of 36 patients with a diagnosis of HIS by pathology; 94% of the patients were men, one was a cisgender woman and one a transgender woman. Among the men, 20 (56%) had sexual relations with men (MSM). The median age at diagnosis was 45.5 years. Nearly a third of the patients included were PLHIV (10 patients, 29.4%), and HIV serology data was not available for two patients. Of these, at the time of the HIS diagnosis viral load was available in eight and was undetectable in five. The median CD4+ cell count was 538 (426–889) cells/mm3. No patient met the diagnostic criteria for AIDS. Of the five patients who had a diagnosis of systemic autoimmune disease, three corresponded to inflammatory bowel disease and two of these were treated exclusively with topical immunomodulators. The diagnoses of the other two patients were Behcet's disease and psoriatic arthritis. None of the patients had a history of treatment with other immunosuppressants or biologics and 14 patients (39%) had a history of previous STIs. Thus, it was only in 11 patients (30.5%) that we did not identify any risk factors associated with HIS (STI and HIV infection, MSM or systemic autoimmune disease).

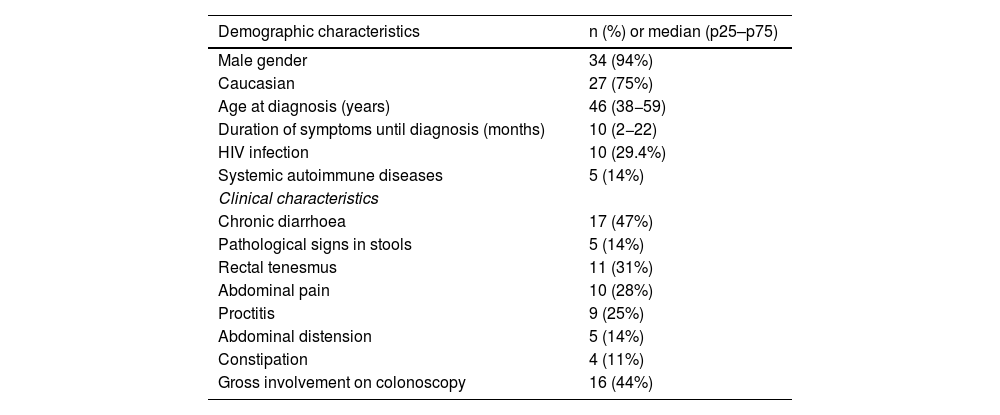

The symptoms were very heterogeneous, with the most common manifestation being chronic diarrhoea (47%). It is noteworthy that in seven patients no gastrointestinal symptoms were identified. Table 1 shows the symptoms and demographic characteristics collected.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort. Data expressed as absolute number and percentage in the qualitative variables, and as median (p25–p75) in the quantitative variables.

| Demographic characteristics | n (%) or median (p25–p75) |

|---|---|

| Male gender | 34 (94%) |

| Caucasian | 27 (75%) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 46 (38−59) |

| Duration of symptoms until diagnosis (months) | 10 (2−22) |

| HIV infection | 10 (29.4%) |

| Systemic autoimmune diseases | 5 (14%) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Chronic diarrhoea | 17 (47%) |

| Pathological signs in stools | 5 (14%) |

| Rectal tenesmus | 11 (31%) |

| Abdominal pain | 10 (28%) |

| Proctitis | 9 (25%) |

| Abdominal distension | 5 (14%) |

| Constipation | 4 (11%) |

| Gross involvement on colonoscopy | 16 (44%) |

The 36 patients in the cohort underwent a colonoscopy study, although gross changes were identified in fewer than half of those (16; 44%). The colon is the intestinal segment in which spirochetes were most frequently detected (20 cases; 56%), although the location of the infection spanned from distal sections with involvement of the ileocaecal valve (three cases, 8%) to exclusive involvement of the rectosigmoid colon (six cases; 17%). The gross involvement observed in the colonoscopies was very heterogeneous, ranging from mild colitis with perilesional erythema to ulcerated lesions, although spirochetes was not identified in a large proportion of the samples that were analysed. Local histological changes directly associated with the presence of spirochetes were found in only seven patients (19%). A stool PCR study was performed in 13 patients (nine cases due to B. aalborgi and four due to B. pilosicoli).

Antibiotic therapy was not prescribed in 13 patients (36%) due to the absence of gastrointestinal symptoms or because the clinician did not consider the finding of intestinal spirochetosis consistent with the patient's symptoms. In the subsequent three months, none of these patients experienced worsening symptoms that required antibiotic therapy for HIS, and in only one case was this information not obtained due to a loss to follow-up. In those patients in whom antibiotic therapy was prescribed, 20 (20/23, 87% of those treated) received metronidazole in monotherapy and the most frequently chosen regimen was 500 mg every eight hours for 10 days. Other regimens used included the combination of metronidazole with rifaximin or monotherapy with doxycycline; the latter selected in cases of coinfection with lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV). At three months of follow-up, no recurrences of the disease were recorded, but there was one case of clinical recurrence accompanied by histological confirmation 24 months after treatment of the first episode.

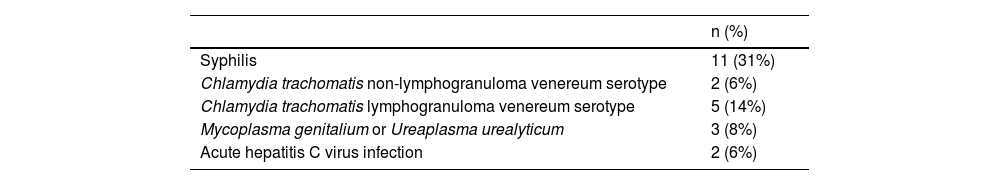

Other sexually transmitted infections and differential characteristics in PLHIVOf the 14 patients (39%) who had a history of STIs in the period between diagnosis of HIS and up to two years prior (Table 2), the most commonly diagnosed STIs were syphilis (five early latent cases, five late latent cases and only one primary syphilis) and LGV. Seven of these episodes were diagnosed concomitantly with HIS: three cases of LGV, two of syphilis (one case of early latent syphilis and the other of late latent syphilis), one of proctitis due to Mycoplasma genitalium and one of HIV infection. In our cohort, there were no cases of gonococcal infection or genital herpes recorded.

When comparing PLHIV with the rest of the cohort, we identified that 90% of the PLHIV had a history of previous STIs compared to 28% of the patients without HIV infection (p = 0.004). The most common STI was syphilis (80% vs. 15.8%; p = 0.01). All cases of infection due to Mycoplasma genitalium or Ureaplasma urealyticum or acute hepatitis C virus infections were in PLHIV.

There were no statistically significant differences in clinical manifestations between PLHIV and the rest of the patients. However, it is noteworthy that PLHIV more frequently had a normal colonic mucosa (20% vs. 58%, p = 0.063), although there were no differences in terms of the frequency of histological abnormalities or the anatomical location of the infection. There were also no differences in terms of the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy (p = 0.64).

DiscussionIn our retrospective review of 36 cases, we found that, although HIS has a very heterogeneous clinical course, most cases occur in men who have sex with men and with a history of STIs, and these are even more frequent in PLHIV.

The main mechanism of transmission is the faecal-oral route, which could explain the findings of HIS in patients without the risk factors described.2 In the first series published, sexual transmission through the faecal-oral route was already considered a fundamental mechanism of transmission in HIS,14 though this aspect is clearer in more recent studies. Chichón et al. contribute a series of nine cases in which the majority had concomitant STIs and two cases were PLHIV.20 Garcia-Hernandez et al. describe in detail six cases diagnosed in centres for sexual and reproductive health in Catalonia.21 All were men who had sex with men and half were PLHIV. Most reported not using a condom and had a median of five sexual partners in the previous six months. Gonococcal proctitis was diagnosed concomitantly in two cases, in one case proctitis due to C. trachomatis and there were two cases with amoebiasis and intestinal giardiasis. The low number of concomitant STIs in our study compared with the above publication can be explained by the different characteristics of the centres. In the STI centres, a detailed sexual history and systematic screening are carried out on a regular basis. In our retrospective study, this information was only systematically collected in the histories of PLHIV, while diagnostic studies in non-HIV patients were performed in a symptom-oriented manner. Although in our study we did not have detailed information available on sexual behaviour and number of sexual partners, the epidemiological characteristics similar to published studies, the history of STIs in previous years and the fact that one in four patients diagnosed had proctitis, support the mechanism of sexual transmission. This fact has been reflected in the latest update to the European guideline on the management of proctitis caused by sexually transmissible pathogens from the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, with intestinal spirochetosis being added as a cause of infectious proctitis.16

In our series, the most frequently diagnosed STI was syphilis, which affected almost a third of the patients studied. This data contrasts with the very few reported cases of syphilis diagnosed in patients with HIS, although most of the published studies do not include systematic screening for STIs.15 One aspect that remains unclear would be whether the high frequency in the diagnosis of syphilis in our series could be due to a false positive because of a cross-reaction with spirochetes. Both treponemal and non-treponemal syphilis serology may have cross-reactions with other spirochetes of the same genus and of different genera such as Borrelia spp. or Leptospira spp., although the existing information in this regard is very scarce.22,23 Despite this conundrum, we believe that the diagnostic precision provided in our study by the combination of pathological and microbiological studies makes this unlikely. Further, if false positives were so common, the syphilis diagnosis rates in other series should be higher than they have been.

The manifestations and clinical spectrum of HIS are highly variable and there is no characteristic symptom, although as we described in our cohort, chronic diarrhoea is the most common manifestation. An interesting point is the hypothesis that spirochetes could be involved in the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome, which could dispel doubts about the pathogenic role of these bacteria.8,24 These studies highlight the predominantly colonic involvement and the absence of specific gross pathological findings in HIS, as we have observed in our study. In terms of diagnostic techniques, most studies predominantly rely on the pathological study of the samples, although the introduction of PCR for Brachyspira spp. and immunohistochemical techniques have made it possible to optimise diagnostic yield.3,13,14,21 It has been demonstrated that B. pilosicoli is susceptible to metronidazole, ceftriaxone, meropenem, tetracyclines, moxifloxacin and chloramphenicol.25 The regimens used for the treatment of HIS are very diverse both in terms of antimicrobials and in dose and duration, which precludes comparisons between different studies.2,24 The most frequently used antibiotic in our study was metronidazole, with a good response, except in one case where the symptoms recurred. The fact that 36% of patients did not receive any treatment is noteworthy, and can be explained by the fact that seven patients had no gastrointestinal symptoms and that in many the diagnosis of HIS was incidental.

There are studies that suggest that the incidence of intestinal spirochetosis is higher in PLHIV,13 although this aspect is not completely clear and does not seem to be related to immunological abnormality because the cases of extensive involvement in contexts of advanced immunosuppression are anecdotal.26 Generally, HIS in PLHIV occurs in individuals with a good immunovirological status and no history of AIDS.14,15,20 Although there are indications that the most common clinical manifestation in these cases would be chronic diarrhea,13,15 in our study we were unable to find clinical differences between PLHIV and the rest of the patients. The differential characteristics in this group of patients in our study are the higher frequency of STIs in the previous two years, which would support the mechanism of sexual transmission, and the absence of gross abnormalities or minor abnormalities on colonoscopy. This fact, which has not previously been described, should be confirmed in future studies that systematically and prospectively analyse the presence of HIS in PLHIV and uninfected controls.

In conclusion, HIS could be a new STI given the high number of men, particularly men who have sex with men, and the history of previous STIs in patients diagnosed with this entity. Prospective studies that systematically examine associated risk factors are needed to clarify the pathogenic role of intestinal spirochetes, especially in PLHIV.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.