Despite the decrease of hepatitis C in Spanish prisons in the last years, it still remains a reservoir for infection. The aim of this work is to analyze the characteristics of these patients and the response to antiviral treatment over the last 18 years.

MethodsRetrospective observational study in inmates of Araba penitentiary center diagnosed with HCV infection between 2002 and 2020.

A descriptive analysis of patient characteristics and the response to the three antiviral treatment modalities was performed: peg-interferon and ribavirin, peg-interferon, ribavirin and a first-generation protease inhibitor and different combinations of direct-acting antivirals.

ResultsA total of 248 antiviral treatments were prescribed. Treatment response rate up to 2015 was 65% and 93,7% after that year. Interferon non-responders were the main cause of non-response to treatment in periods 1 and 2 (40%–50%). Conversely, in period 3 viral breakthrough (67%) was the main culprit.

ConclusionAfter 18 years, active hepatitis C infection in prison inmates has resolved with treatment according to clinical criteria. Therefore, the stay in prison may represent an opportunity to reduce the reservoir of the disease in the community, together with continued health care for those released from prison.

A pesar de la disminución de la prevalencia de la infección de la hepatitis C en las prisiones españolas en los últimos años, sigue existiendo un reservorio de la infección. El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar las características de estos pacientes y la respuesta al tratamiento antiviral a lo largo de los últimos 18 años.

MétodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo en internos diagnosticados de infección por VHC entre los años 2002 y 2020 y que llevan más de 6 meses institucionalizados en el centro penitenciario Araba.

Se realiza un análisis descriptivo de las características de los pacientes y de la respuesta a las tres modalidades de tratamientos antivirales: peg-interferón y ribavirina, peg-interferón, ribavirina y un inhibidor de la proteasa de primera generación y diferentes combinaciones de antivirales de acción directa.

ResultadosSe prescribieron en total 248 tratamientos antivirales. Hasta 2015 el 65% de los sujetos estudiados respondieron al tratamiento, y después de 2015 alcanzó el 93,7%. Los pacientes no respondedores fueron la causa principal de no respuesta al tratamiento en los periodos 1 y 2 (40%–50%). Mientras que en el periodo 3 el motivo mayoritario fue viral breakthrough (67%).

ConclusiónDespués de 18 años de experiencia tratando a todos los pacientes que ingresan en prisión con VHC según criterio clínico, se ha logrado remitir la infección activa de hepatitis C. Por tanto, la estancia en prisión en sí misma y conjuntamente con la atención sanitaria continuada de aquellos sujetos que son liberados de la prisión, puede constituir una oportunidad para disminuir el reservorio de la enfermedad también en la comunidad.

The World Health Organization estimates the number of people suffering from chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection at 71 million, with a prevalence of 0.5%–2.3%.1 According to epidemiological studies carried out in Spain between 2017 and 2018, the prevalence of people with antibodies against HCV in the general population between 20 and 80 years of age was 0.85%, while the prevalence of active infection was 0.22%.2

It is estimated that the prevalence of HCV infection in people institutionalised in prison is up to 10 times higher than in the general population.3 These figures vary depending on the geographical location of the prison, the country of origin of the inmates, previous incarceration or the number of intravenous drug users (IVDU).4 It has also varied over the last 18 years, with a reduction from 39% in 2002 to 10.6% in 2018.5 In the Araba prison, the values recorded during this period of time range from 44.7% in 2002 to 16.6% in 2017.6

The main reason for this decrease in the prevalence of active HCV infection is the increase in the efficacy of antiviral treatments.7 Other reasons are change in the route of administration of substances of abuse and the implementation of needle exchange programmes and opiate withdrawal programmes in prisons.

Despite this, the prevalence of active infection among institutionalised prison patients continues to be high and constitutes an important reservoir of infection.5,8 For this reason, prisons become key elements in HCV treatment programmes in the fight to eliminate the virus.9

Long prison terms make it possible for prison health services to implement prevention programmes to control chronic diseases such as HCV and HIV infections, with benefits for the public health of the community.9,10 However, and despite the fact that the principles of equity in access to health resources must be applied,11 there are still many countries without specific prevention plans and with different levels of coverage of HCV harm reduction interventions, tests and treatment in prison patients.11

In 2016, the World Health Organization, in tune with other health institutions and governments, established a global strategy in the health sector on viral hepatitis, with the aim of eliminating it by the year 2030. The strategy defines elimination as an 80% reduction in new HCV infections and a 65% reduction in HCV mortality.12 In addition, in 2017 the micro-elimination strategy aimed at risk populations such as those institutionalised in prison was proposed.13 In this line, national and regional strategic plans have been developed.14

The low treatment rate of these patients and the varied response rate before the introduction of direct-acting antivirals motivated this study, the objective of which was to analyse the characteristics of patients with HCV infection at the Araba prison and the response to antiviral treatment over the past 18 years.

MethodsThis was a retrospective observational study of all the treatments prescribed at the Araba prison between November 2002 and October 2020. This centre houses an average of 650 inmates, 10% of whom are women.

The study was approved by the Hospital Universitario de Araba [Araba University Hospital] (HUA) Independent Ethics Committee (File. 2020-088).

The treatments administered throughout the study period varied in accordance with the changing clinical practice guidelines. Three study periods were defined according to the antiviral treatment used:

- -

Period 1: November 2002–September 2012, patients treated with peginterferon and ribavirin.

- -

Period 2: October 2012–December 2014, patients treated with peginterferon, ribavirin and a first-generation protease inhibitor (telaprevir).

- -

Period 3: January 2015–October 2020, different combinations of direct-acting antivirals were included.

Those patients who met the following criteria were included in the treatment programme: detectable HCV viral load (HCV-RNA), any HCV genotype (except in the second period when only genotype 1 was included), stable mental illness with control coordinated with psychiatry and HIV infection with virological and immunological control (undetectable viral load for at least six months and CD4+ T lymphocytes greater than 500 cells/mm3). Patients with severe uncontrolled psychiatric illness and estimated stay in prison shorter than the treatment time were excluded. In the first period, patients with chronic liver disease, other liver diseases (haemochromatosis, autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson's disease) and uncontrolled epilepsy were also excluded.

From 2002 to 2011, the first consultation was carried out in person at the hospital, with subsequent telephone follow-up through the prison doctor. As of 2011, patients were seen in a room located at the prison equipped to carry out a telemedicine consultation with the hospital's infectious disease doctor. This consultation was attended in person by the primary care medical team and the hospital pharmacy medical team along with the patient. The prescription of treatment, supervision, monitoring of tolerability and adherence, and performance of laboratory tests were the responsibility of the prison medical team. Patients were followed up according to the treatment protocols established in each case.

By reviewing the medical records, all the variables that affected the response to treatment were collected: age at the start of treatment, gender, HCV genotype, number of HCV-RNA copies, degree of fibrosis prior to treatment (measured by transient elastography, FibroScan®) and HIV coinfection along with clinical, immunological and virological parameters (CDC classification15). The treatments for treating a reinfection, the place where the HCV reinfection had occurred (outside or inside the prison) and the response to that therapy were also collected. Reinfection was defined as those cases of patients who, having been previously treated and with sustained virological response (SVR), once again manifested detectable HCV-RNA.

The HCV viral load was analysed with the COBAS® Amplicor and COBAS® TaqMan® 48 (Roche) equipment. HCV genotype was determined using real-time PCR for the qualitative identification of HCV genotypes 1–6 and subtypes A and B of genotype 1 in plasma or serum.

SVR was defined as undetectable HCV-RNA at 12 or 24 weeks after completion of treatment, depending on the therapy received.

The reason for non-response to treatment was classified as: non-response to treatment, relapse, viral breakthrough, suspension due to adverse effects and abandonment of therapy. Relapse was defined as undetectable HCV-RNA at the end of treatment, but detectable during subsequent follow-up. Viral breakthrough was defined as the reappearance of the HCV viral load after a negative viral test result during treatment.

Leaving the prison (for release or transfer to another prison) and death from other causes unrelated to liver disease were considered losses to follow-up for the purposes of response to treatment.

Statistical planThe general description of the patient sample uses mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, and frequency and proportion for categorical variables.

The characteristics of the patients and for each of the three established time periods (2002–2012, 2012–2014 and 2015–2020) are described. A descriptive intention-to-treat and per protocol analysis of the antiviral treatments and the corresponding response to the treatments throughout the entire time period was conducted.

A descriptive analysis was also conducted for the reinfected group.

Statistical analysis was performed with version 23 of the IBM SPSS® software platform for Windows.

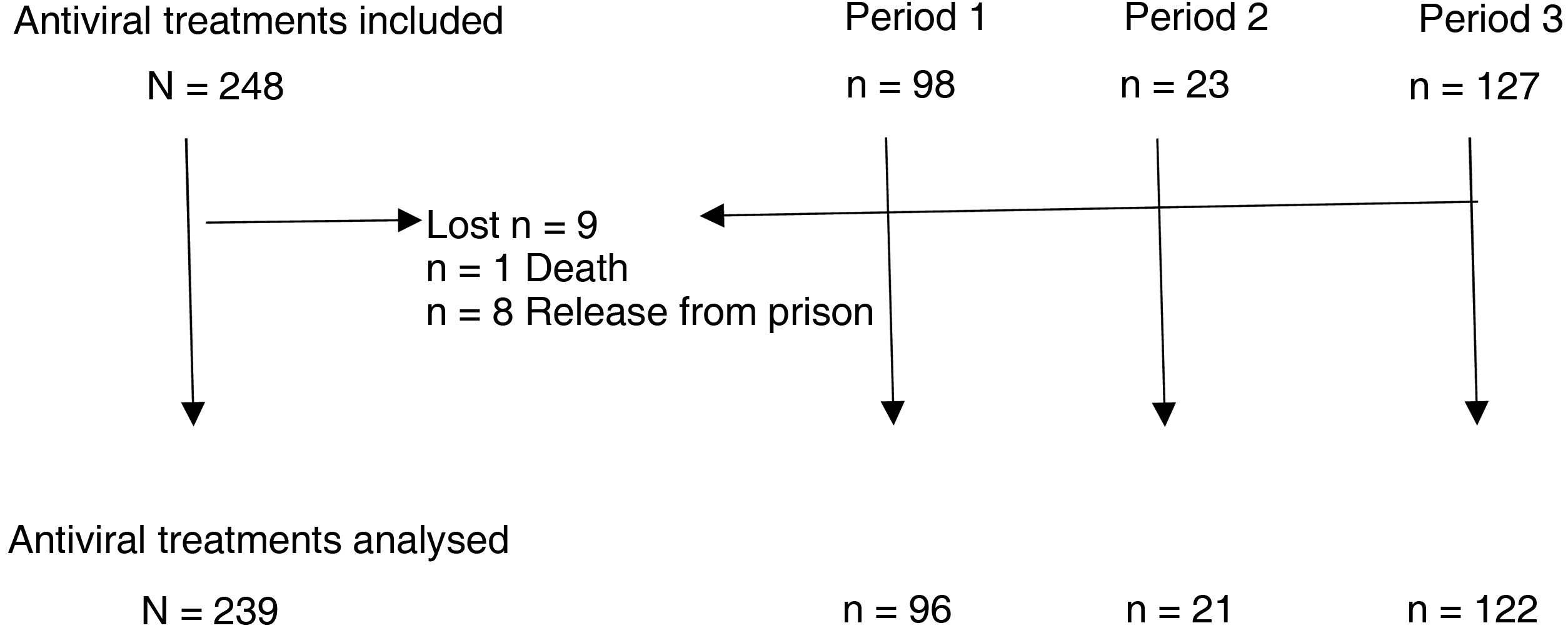

ResultsBetween January 2002 and October 2020, a total of 248 antiviral treatments were prescribed in this prison. Follow-up could not be completed in nine patients, in one of them due to death and in the rest due to release from prison (three of them due to transfer to another prison and five due to discharge from prison or release) (Fig. 1).

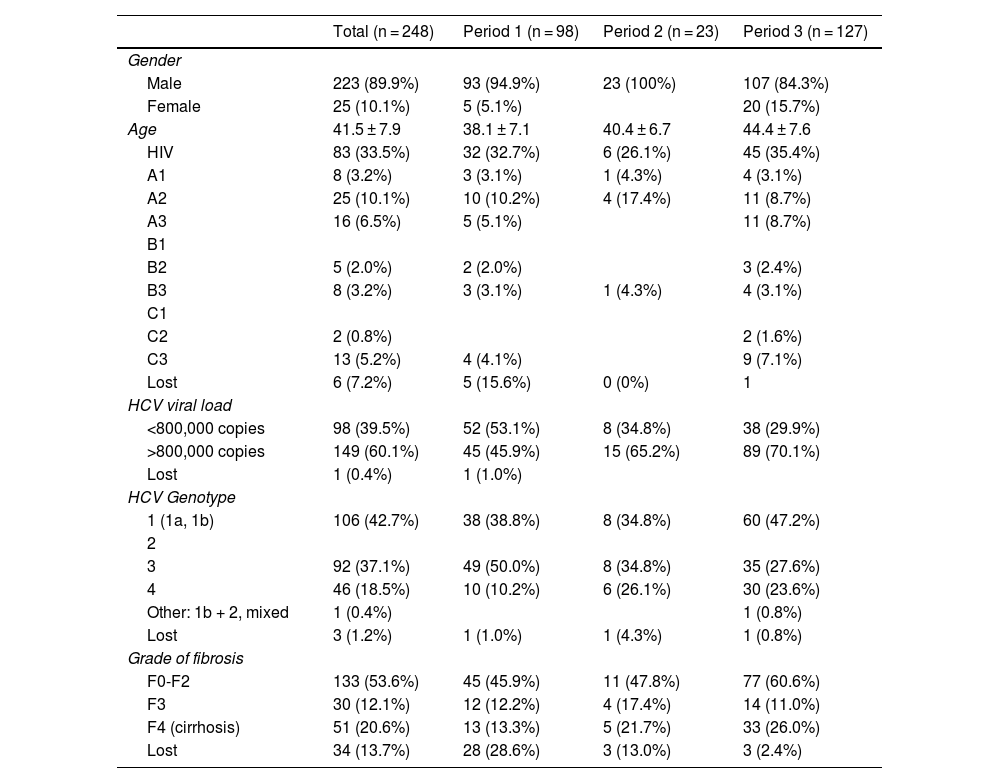

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the patients receiving antiviral treatment. Overall, 90% were men, with a mean age of 41 years, 33% had HIV co-infection, 60% had an HCV viral load greater than 800,000 copies, and 53% had fibrosis grade F0-F2.

Description of the study population.

| Total (n = 248) | Period 1 (n = 98) | Period 2 (n = 23) | Period 3 (n = 127) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 223 (89.9%) | 93 (94.9%) | 23 (100%) | 107 (84.3%) |

| Female | 25 (10.1%) | 5 (5.1%) | 20 (15.7%) | |

| Age | 41.5 ± 7.9 | 38.1 ± 7.1 | 40.4 ± 6.7 | 44.4 ± 7.6 |

| HIV | 83 (33.5%) | 32 (32.7%) | 6 (26.1%) | 45 (35.4%) |

| A1 | 8 (3.2%) | 3 (3.1%) | 1 (4.3%) | 4 (3.1%) |

| A2 | 25 (10.1%) | 10 (10.2%) | 4 (17.4%) | 11 (8.7%) |

| A3 | 16 (6.5%) | 5 (5.1%) | 11 (8.7%) | |

| B1 | ||||

| B2 | 5 (2.0%) | 2 (2.0%) | 3 (2.4%) | |

| B3 | 8 (3.2%) | 3 (3.1%) | 1 (4.3%) | 4 (3.1%) |

| C1 | ||||

| C2 | 2 (0.8%) | 2 (1.6%) | ||

| C3 | 13 (5.2%) | 4 (4.1%) | 9 (7.1%) | |

| Lost | 6 (7.2%) | 5 (15.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 |

| HCV viral load | ||||

| <800,000 copies | 98 (39.5%) | 52 (53.1%) | 8 (34.8%) | 38 (29.9%) |

| >800,000 copies | 149 (60.1%) | 45 (45.9%) | 15 (65.2%) | 89 (70.1%) |

| Lost | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (1.0%) | ||

| HCV Genotype | ||||

| 1 (1a, 1b) | 106 (42.7%) | 38 (38.8%) | 8 (34.8%) | 60 (47.2%) |

| 2 | ||||

| 3 | 92 (37.1%) | 49 (50.0%) | 8 (34.8%) | 35 (27.6%) |

| 4 | 46 (18.5%) | 10 (10.2%) | 6 (26.1%) | 30 (23.6%) |

| Other: 1b + 2, mixed | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.8%) | ||

| Lost | 3 (1.2%) | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Grade of fibrosis | ||||

| F0-F2 | 133 (53.6%) | 45 (45.9%) | 11 (47.8%) | 77 (60.6%) |

| F3 | 30 (12.1%) | 12 (12.2%) | 4 (17.4%) | 14 (11.0%) |

| F4 (cirrhosis) | 51 (20.6%) | 13 (13.3%) | 5 (21.7%) | 33 (26.0%) |

| Lost | 34 (13.7%) | 28 (28.6%) | 3 (13.0%) | 3 (2.4%) |

Period 1: between January 2002 and September 2012, patients treated with peginterferon and ribavirin.

Period 2: between October 2012 and December 2014, patients treated with peginterferon, ribavirin and a first-generation protease inhibitor.

Period 3: between January 2015 and October 2020, different combinations of direct-acting antivirals were included.

In total, 51.2% of patients were treated between 2015 and 2020, 39.5% between 2012–2014 and 9.3% between 2002−2012. An increase in age is observed in each of the periods analysed, as well as in the viral load and the degree of fibrosis F0-F2 and F4. Genotype 3 is the most common in the first period while in the last it is genotype 1.

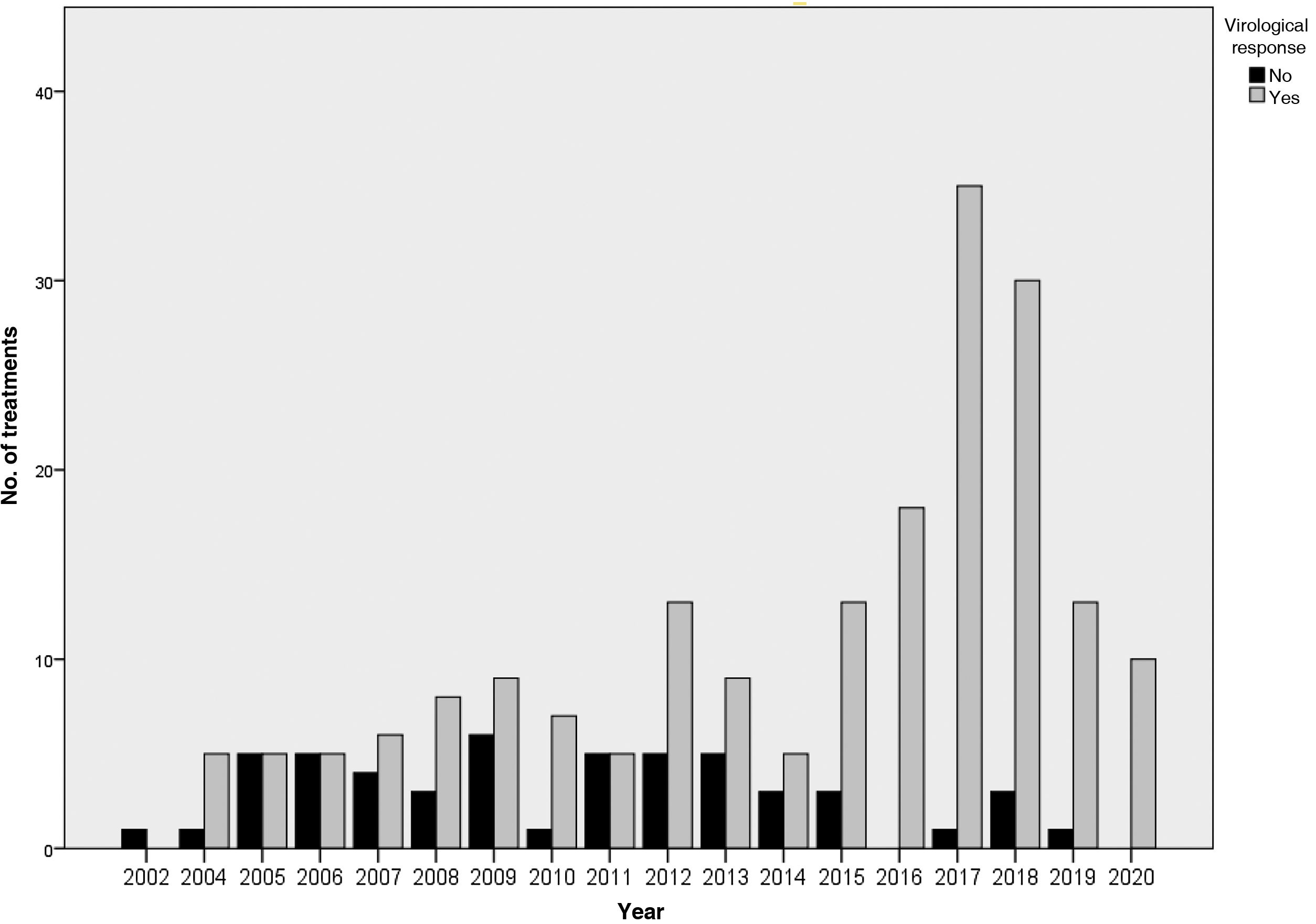

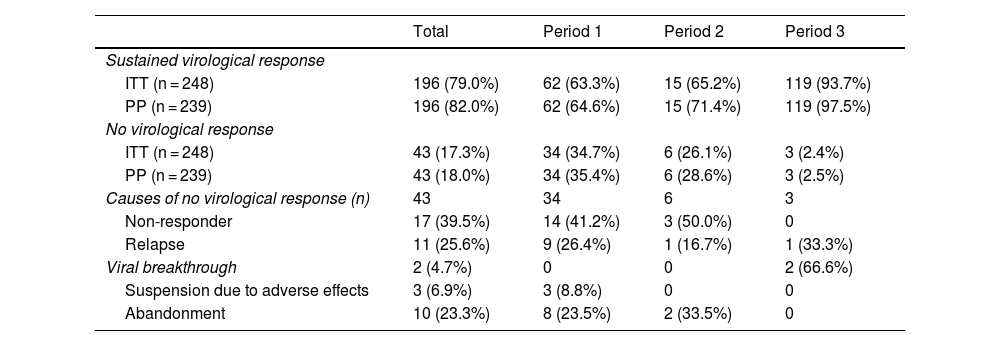

The results of the treatments are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 2. Until 2015, 63%–65% of the subjects studied responded to treatment, while after 2015 the SVR was 93.7%. Analysing the data per protocol and excluding patients lost to follow-up, the SVR percentage is 64%–71% and 97.5%, respectively. At the end of the study period, the number of patients with undetectable HCV viral load who had been imprisoned for more than six months was 100%.

Results of antiviral treatments in the three periods analysed.

| Total | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained virological response | ||||

| ITT (n = 248) | 196 (79.0%) | 62 (63.3%) | 15 (65.2%) | 119 (93.7%) |

| PP (n = 239) | 196 (82.0%) | 62 (64.6%) | 15 (71.4%) | 119 (97.5%) |

| No virological response | ||||

| ITT (n = 248) | 43 (17.3%) | 34 (34.7%) | 6 (26.1%) | 3 (2.4%) |

| PP (n = 239) | 43 (18.0%) | 34 (35.4%) | 6 (28.6%) | 3 (2.5%) |

| Causes of no virological response (n) | 43 | 34 | 6 | 3 |

| Non-responder | 17 (39.5%) | 14 (41.2%) | 3 (50.0%) | 0 |

| Relapse | 11 (25.6%) | 9 (26.4%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Viral breakthrough | 2 (4.7%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (66.6%) |

| Suspension due to adverse effects | 3 (6.9%) | 3 (8.8%) | 0 | 0 |

| Abandonment | 10 (23.3%) | 8 (23.5%) | 2 (33.5%) | 0 |

ITT: intention to treat (with losses); PP: per protocol (no losses).

Period 1: between January 2002 and September 2012, patients treated with peginterferon and ribavirin.

Period 2: between October 2012 and December 2014, patients treated with peginterferon, ribavirin and a first-generation protease inhibitor.

Period 3: between January 2015 and October 2020, different combinations of direct-acting antivirals were included.

The main reason for non-response in the first two periods was non-response to treatment (41% in 2002–2011 and 50% in 2012–2014), while in the last period it was viral breakthrough (67%).

During the 18 years of the study, 12 reinfections were treated in prison, of which 11 were with interferon-free regimens. In total, 83.3% were men, with a mean age of 41.1 years, and 41.4% had HIV coinfection. An SVR was obtained after treatment in 10 of the 12 cases, and in the remaining two cases the final response is unknown; one died of causes unrelated to hepatitis and the other left the prison (discharged or released).

DiscussionUntil 2012, the treatment of choice for HCV was the combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 24–48 weeks. With this combination, SVR rates of around 50% were achieved in patients with genotype 1.16,17 However, there was a high rate of side effects and it was contraindicated in many patients, including those with advanced cirrhosis.18 In Araba Prison, the SVR rate was 63.3%, similar to pivotal clinical trials.

With the arrival of the first-generation protease inhibitors (boceprevir and telaprevir) in 2012, an SVR rate of between 63%–75% was achieved in naïve patients19,20 and between 29%–88% in patients with HCV genotype 1 without response to treatment with dual therapy.21,22 In the Araba prison, an SVR of 65.2% was obtained.

With the marketing of direct-acting antivirals from 2015, higher SVR rates close to 100% began to be shown.23,24 In the Araba prison, the SVR rate reached was 93.7%. If we exclude patients lost to follow-up upon release from prison, this rate would rise to 97.5%, similar to that observed in pivotal studies of the different direct-acting antiviral drugs.

Therefore, taking into account that all patients who had been imprisoned for more than six months with HCV are treated according to clinical criteria and that, after 18 years, close to 100% have an undetectable viral load, prison stay seems to be an ideal time to treat these patients. It also makes a great community contribution to infection control.25

Consequently, non-response rates to treatment have decreased over time, from 26% to 34% with initial interferon-based treatment regimens, to 2.4% with interferon-free regimens. The main reason for non-response in the former was lack of response to treatment (41%–50%), while with interferon-free treatments, it was due to viral breakthrough (66%). In addition, in the interferon-free treatments, we did not find any cases of lack of response due to abandonment or adverse effects.

In the scientific evidence published to date, we found results similar to ours for interferon-free treatments, with rates of non-response due to abandonment and adverse effects of 0.47% and 0.48%.26,27 For treatments with interferon, non-response rates of 22% are reported,28 although the main reasons are release from prison (36%) and adverse effects (15.5%). Finally, a recent systematic review29,30 highlights great variability in the reasons for non-response to treatment in the different studies included, in both interferon-containing and interferon-free regimens.

Loss to follow-up due to leaving the prison was 3.2%. Discontinuation of treatment due to leaving prison thus poses a challenge that could be resolved with the continuation of therapeutic care for released inmates through adequate coordination between the prison and community health systems.13,28 In addition, strategies and protocols directed especially towards the prevention of reinfections and people with cirrhosis that require subsequent control in the community would be necessary.

One of the limitations of the study is that the prison patients were managed within a supervised framework and those who continued the treatment at another centre were not counted, although in most cases the final response to treatment was known. Released inmates were referred to their reference hospital, while for prisoners transferred to other prisons, the corresponding health service was contacted to find out the final result. In order to minimise the possible associated information bias, an intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis was performed.

However, the number of patients who refused treatment and the reasons for it were not determined.

FundingThis study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest.

To Javier Marijuan García, for his collaboration in data acquisition from the beginning of the study in 2002 until his retirement in 2018.

To María Isabel Santamaría Mas, for her collaboration in the acquisition of liver fibrosis grade data from the beginning of the study in 2002 until her retirement in 2018.