To describe an outbreak of KPC-3-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPN) and determine the diagnostic efficacy of MALDI-TOF in its detection.

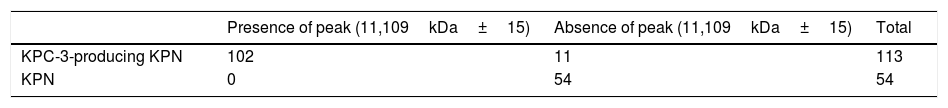

MethodsRetrospective study of the KPC-3-KPN isolated in 2 hospitals in Ciudad Real. The peak at 11,109kDa±15 was sought in the KPN spectra provided by MALDI-TOF.

ResultsWe isolated 156 KPN strains that carried the blaKPC-3 gene, with a unique profile belonging to ST512 (31 strains studied). There was 25% of infected patients, 84% were nosocomial or related to health care and 93% had some underlying disease (31% of exitus in the first month).

The detection of the peak showed 90% sensitivity and 100% specificity.

ConclusionsWe detected the clonal spread of a KPN ST512 strain producing KPC-3 in 3 hospitals in Ciudad Real. In addition, we show the profitability of MALDI-TOF in the early detection of KPC-KPN.

Describir un brote por Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPN) productora de KPC-3 y determinar la eficacia diagnóstica de MALDI-TOF en su detección.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo de las KPN-KPC-3 aisladas en 2 hospitales de Ciudad Real. Se buscó el pico a 11,109kDa±15 en el espectro proporcionado por MALDI-TOF para KPN.

ResultadosSe aislaron 156 cepas de KPN que portaban el gen blaKPC-3, con un único perfil perteneciente al ST512 (31 cepas estudiadas). Hubo un 25% de infectados. Un 84% tuvieron origen nosocomial o relacionado con la asistencia sanitaria. El 93% tenía alguna enfermedad de base (31% de exitus en el primer mes).

La detección del pico mostró una sensibilidad del 90% y una especificidad del 100%.

ConclusionesDetectamos la diseminación clonal de una cepa de KPN ST512 productora de KPC-3 en 3 hospitales de Ciudad Real. Además, evidenciamos la rentabilidad de MALDI-TOF en la detección precoz de KPN-KPC.

Since 2005, when the first carbapenemase-producing enterobacteria (CPE) were detected in Spain, the country has borne witness to a greater and greater decrease in these bacteria at different healthcare levels, with an increase in hospitals affected by outbreaks.1,2 Reservoirs for resistant micro-organisms have also been established at different levels.3

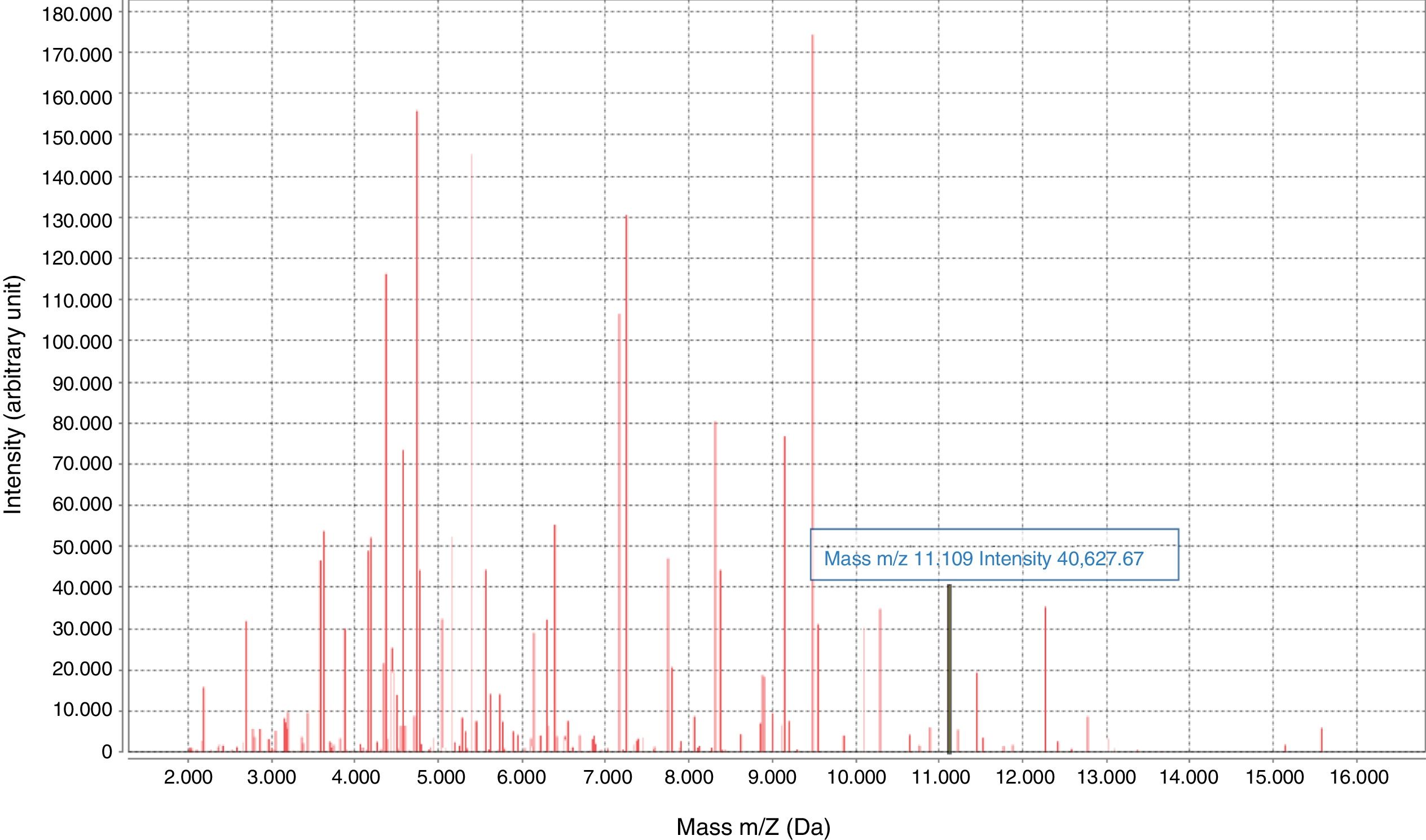

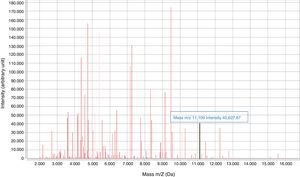

Early diagnosis of infections caused by CPE is essential for implementing infection control measures and administering effective antibiotic therapy. In recent years, rapid phenotypic and molecular tests have been developed to detect CPE, including MALDI-TOF technology.4–7 In 2014, an 11,109-Da peak was identified on the spectrum provided by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MS), corresponding to the pKpQIL_p019 protein, encoded in a plasmid carrying the blaKPC gene.8

Our objectives were to review KPC-3 carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPN) isolates from 2 hospitals in Castilla–La Mancha, and to determine the diagnostic efficacy of MALDI-TOF in their detection.

Material and methodsDesign and variables collectedA retrospective study of the KPC-3–producing KPN strains isolated at 2 hospitals in Ciudad Real (Hospital General La Mancha Centro [Central La Mancha General Hospital], HGMC, and Hospital General de Tomelloso [Tomelloso General Hospital], HGT) between 2016 and June 2019 (one isolate per patient).

Patients’ medical records were reviewed and the following data were collected: name, age, sample type, strain sensitivity, infection acquisition (hospital-acquired, community-acquired or healthcare-related: nursing home or admission in the previous 6 months), underlying diseases, antibiotic therapy received in the previous 6 months, instrument use (catheter, parenteral/enteral nutrition or other), antibiotic therapy received to treat the infection, and death within a month from isolation.

Microbiology and clonality studyIdentification of bacteria and testing for sensitivity to antimicrobials were performed using the Vitek2® and Vitek-MS® system (version 3.2 IVD) and Etest diffusion gradient strips (BioMérieux), according to EUCAST criteria.

In cases in which we detected a decrease in sensitivity to any carbapenem, we confirmed the presence or absence of carbapenemase production using the β CARBA test (Bio-Rad); in positive cases, the phenotype study was extended through synergy of meropenem with phenylboronic acid, cloxacillin, dipicolinic acid and sensitivity to temocillin (Rosco Diagnostica). To detect intestinal colonisation by the study strain, chromID™ Carba SMART Agar screening plates (BioMérieux) were used.

A total of 31 isolates were sent to the Antibiotic Resistance Laboratory at the Centro Nacional de Microbiología [National Centre for Microbiology] for genotypic characterisation of the mechanism of resistance involved (PCR and sequencing) and molecular epidemiology testing using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) following digestion of total DNA with the XbaI restriction enzyme and multilocus sequence typing (MLST). Representative strains were selected (isolates from the 4 study years, from different sources and locations).

The KPC-specific peak (11.109kDa±15)8 was detected prospectively (January 2019) by means of a visual search on the spectrum provided by MALDI-TOF for KPN isolates.8 The isolates came from colonies and positive blood cultures following short-term subculture (4h on chocolate agar). Only the matrix was added to the colony, with processing once dry. The results were compared to the results of the β CARBA test and the disc synergy test.

Epidemiological studyIntestinal colonisation testing was performed on all patients with positive clinical samples and those with whom they shared a room at the time of isolation. To do so, weekly rectal swabs were taken until hospital discharge or acquisition of 3 consecutive negative colonisation results.

In 2019, an active search was conducted for a possible water reservoir (traps, taps and drains); paper dispensers at both hospitals were also examined as potential reservoirs.

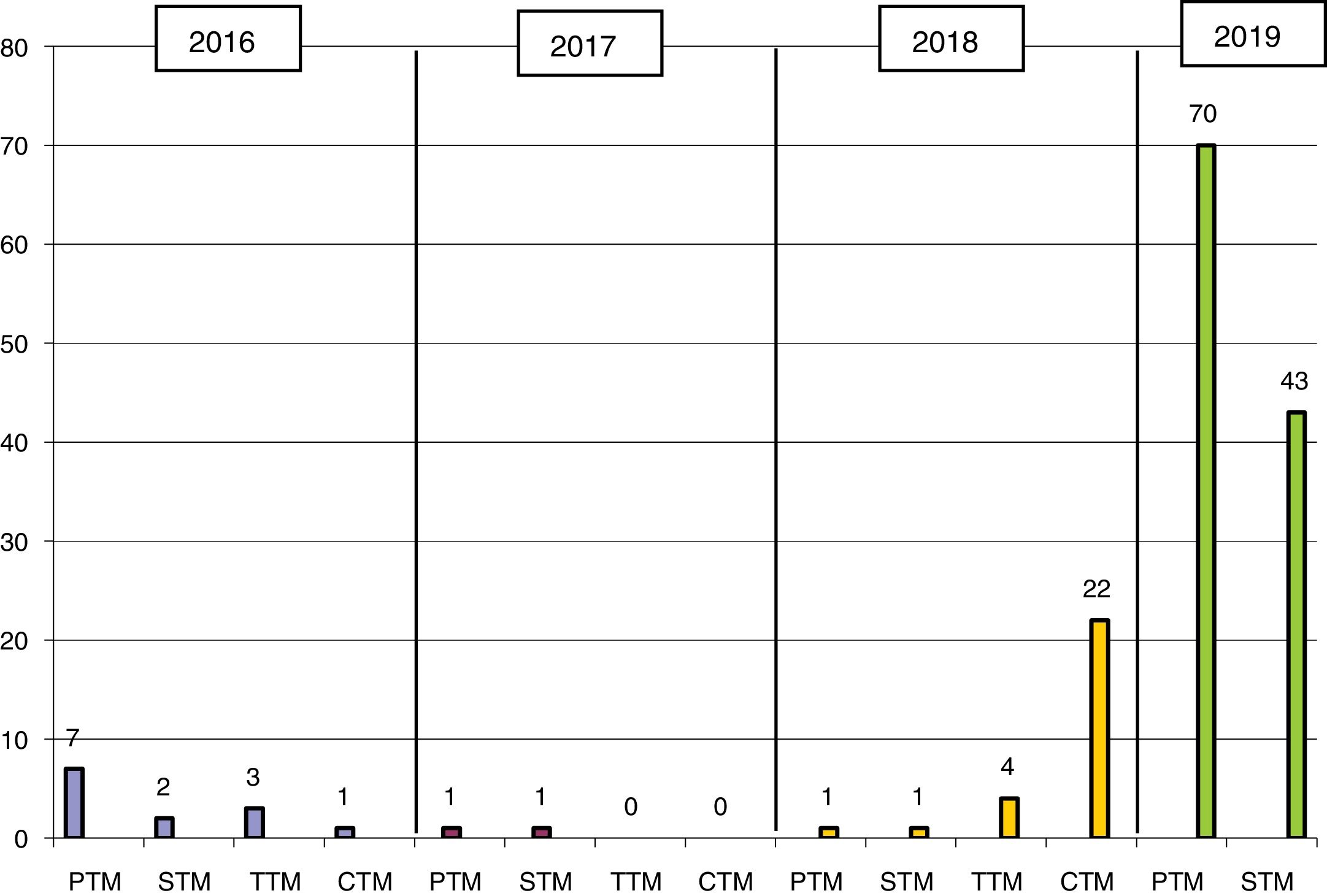

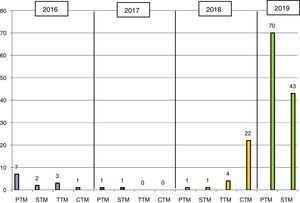

ResultsKPC-3–producing KPN was first isolated in 2016 at HGMC in an outbreak that affected 13 patients (11 at HGMC and 2 at HGT) and was managed with standard measures (Fig. 1). The first isolate at HGT came from a patient who had been admitted to HGMC in the previous month; the second isolate was 6 months later on the same hospital ward. In 2018, a patient who had been hospitalised at the same time and on the same ward as the two patients in 2016 was admitted to HGT. In August 2018, a second outbreak affected 28 patients (26 at HGT and 2 at HGMC). In 2019, it was once again spread widely by both hospitals (Fig. 1).

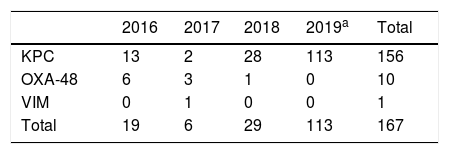

In the study period, 156 KPC-3–producing KPN strains were isolated; these accounted for 90% of all CPE and 93% of carbapenemase-producing KPN in the same period (Table 1). Full sequencing revealed the presence of the blaKPC-3 gene. All the strains studied showed a single PFGE profile belonging to ST512 (one of them had been previously detected at another hospital in the same province).

Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates during outbreak.

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019a | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPC | 13 | 2 | 28 | 113 | 156 |

| OXA-48 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| VIM | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 19 | 6 | 29 | 113 | 167 |

KPN: K. pneumoniae.

The median age of the patients was 83 years (45–98), and 58% were women. Of the samples, 65% were rectal exudate and 24% were urine. There were 3 cases of bacteraemia. 84% were of nosocomial origin and all others were healthcare-related (31% came from nursing homes). 90% had received at least one antibiotic in the previous 6 months, instrument use had occurred in 72% of cases, and 92% had an underlying disease. There was a 31% rate of death in the month of isolation.

The strains showed broad antibiotic resistance, being sensitive only to colistin (apart from 2 strains which tested negative for the mrc gene), tigecycline (24%) and/or gentamicin (62%). 25% of patients were infected (3 previously colonised patients developed an infection); 38% received an aminoglycoside, 31% received a carbapenem and 27% received colistin or tigecycline. 62% received combination therapy.

The characteristic KPC peak (Fig. 2) was detected in 90% of strains carrying the blaKPC-3 gene and enabled direct identification in all blood cultures studied, with a sensitivity of 90%, a specificity and positive predictive value (PPV) of 100% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 75% (Table 2). The rate of correlation with the phenotype tests examined was 100%. Low adherence to proper hand hygiene was seen among the staff involved. We did not detect any environmental reservoir.

We report the clonal spread of an extremely resistant KPC-3–producing KPN ST512 strain among the different healthcare levels in a healthcare area in Castilla–La Mancha (Spain). This clone is commonly associated with multidrug resistance and is considered to be of high epidemiological risk due to its extensive global distribution.9 It was first detected in Spain in 2012 at a hospital in Córdoba, where it caused an outbreak with 67 infected patients;10 the index case came from a hospital in Italy,11 where this clone had been previously reported.12 Following the appearance of the outbreak in our area, the cumulative incidence of CPE went from 0.01 in 2017 to 0.24 in 2018; however, not until 2019 was there rapid spread of the strain due to continuous access on the part of the patients, elderly individuals with multiple diseases, between the internal medicine floor at both hospitals and various long-term care institutions, resulting in an endemic caused by this clone in our healthcare area.

Multiple factors contributed to the spread of these isolates. Given the fact that a reservoir was not located and the high rate of rectal colonisation, indicating cross-contamination among patients and healthcare staff, it was proposed that staff members’ hands be screened. This initiative was ultimately abandoned, given the low rate of compliance with the hand-washing protocol, ranging from 5% to 89%,13 and a dearth of actions to be taken in the event of a positive result.

Visualisation of the characteristic peak on the MALDI-TOF spectrum enabled detection of KPC-3–producing KPN in routine culture identification, though with a rate of diagnostic efficacy lower than that found in other studies,14,15 rendering it the fastest and cheapest phenotypic method for KPC detection. As we did not directly detect carbapenemase, sensitivity for detection will depend on the prevalence of clones carrying the plasmid in a given area. The lack of a peak may have been due to a lack of protein expression or subjectivity in visualising the peak, representing a study limitation. The next step would be an automated search for the peak using the software on the apparatus.14

In conclusion, we detected clonal spread of a strain of KPC-3–producing KPN ST512 at 3 hospitals in Ciudad Real. To date, the measures implemented have not proven effective for controlling the outbreak, giving rise to an endemic situation. We also demonstrated MALDI-TOF’s efficacy in the early detection of these strains, with the clinical implications that this entails, at no additional cost.

Conflicts of interestNone.

We would like to thank Dr Jesús Oteo for his advice.

Please cite this article as: Egea MA, Pitera JG, Vaquero MH, González RC, Ortiz CR, Fuella NL. Diseminación interhospitalaria de Klebsiella pneumoniae ST512 productora de KPC-3. Detección por MALDI-TOF. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:83–86.

This research did not receive a specific support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.