Lyme borreliosis (LB) in the paediatric population is an understudied entity with certain peculiarities. The objective of this study is to describe the characteristics of paediatric patients with LB, and their diagnostic and therapeutic processes.

MethodsDescriptive and retrospective study in patients up to 14 years old with suspected or confirmed LB between 2015 and 2021.

ResultsA total of 21 patients were studied: 18 with confirmed LB (50% women; median age 6.4 years old) and 3 false positive of the serology. Clinical features in the 18 patients with LB were: neurological (3, neck stiffness; 6, facial nerve palsy), dermatological (6, erythema migratory), articular (1), and non-specific manifestations (5). Serological diagnosis was confirmatory in 83.3% of cases. A total of 94.4% patients received antimicrobial treatment (median duration, 21 days). All recovered with resolution of symptoms.

ConclusionsLB diagnosis is difficult in the paediatric population and presents clinical and therapeutic peculiarities, with favourable prognosis.

La borreliosis de Lyme (BL) es una entidad poco estudiada en pediatría, pero con ciertas peculiaridades. El objetivo es conocer las características de los pacientes pediátricos con sospecha y/o confirmación de BL.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo y retrospectivo en menores de 14 años con diagnóstico clínico y/o serológico, sospechoso o confirmado, de BL entre 2015 y 2021.

ResultadosSe estudiaron 21 pacientes: 18 con diagnóstico final de BL (50% mujeres; mediana de edad 6,4 años) y 3 falsos positivos. En los casos de BL, las manifestaciones clínicas presentadas fueron: neurológicas (3, meningitis; 6, parálisis facial), dermatológicas (6, eritema migratorio), articulares (1) e inespecíficas (2). El diagnóstico serológico fue confirmatorio en el 83,3% de los casos. El 94,4% recibió antibioterapia (mediana de duración 21 días) y la evolución fue satisfactoria en todos los casos.

ConclusionesEl diagnóstico de la BL es difícil en la población pediátrica y presenta peculiaridades clínicas y terapéuticas, pero el pronóstico es favorable.

Lyme borreliosis (LB) is the most common zoonosis in the northern hemisphere. In Spain, the estimated incidence in endemic areas in the north-west of the peninsula is 2–3 cases per 100,000 inhabitants/year.1 The LB hospitalisation rate increased by around 175% between 2005 and 2019 in Spain, reflecting the increased incidence of the disease.2

Its clinical manifestations are highly disparate and depend on such factors as the stage of the disease, the genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex, the age of the patient, etc.3 This broad spectrum of symptoms hinders clinical suspicion and diagnosis. Because culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have a low diagnostic yield, serological studies are usually performed for microbiological diagnosis.3,4 A national consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of LB was recently published.5

Asturias is an endemic region for the Ixodes ricinus tick because of its climatic conditions (high humidity and mild temperatures), type of vegetation, extensive cattle farming and wildlife.6 The percentage of ticks infected with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Asturias is estimated to be 4–6.1%.5

In the paediatric population, LB presents with a number of unusual features concerning bite location, predominant clinical manifestations and treatment.7 In light of the increasing incidence in Spain,1 this review was conducted to better understand the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of paediatric patients with suspected and/or confirmed LB, as well as the diagnostic and therapeutic process.

MethodsA descriptive and retrospective study was conducted by reviewing the medical records of patients under 14 years of age with suspected, confirmed or clinically and/or serologically diagnosed LB assessed at the Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias between January 2015 and December 2021.

The variables collected were: age, gender, symptoms, prior contact with ticks, microbiological studies, treatment and outcome. Cases were grouped by symptoms identified at the first appointment.

Serological diagnosis of LB was performed at the Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias Microbiology Laboratory in two stages: chemiluminescence enzyme immunoassay (Liaison®, DiaSorin) as a screening method, and confirmation, in the event of a positive or inconclusive result, by immunoblot (Borrelia LINE IgG/IgM®, Virotech), which detects IgM and IgG for the OspC, VlsE, BmpA, p83, BBa36, BBO323, Crasp3 and pG antigens.

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® 21.0, analysing frequencies and proportions for qualitative variables, and medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for quantitative variables.

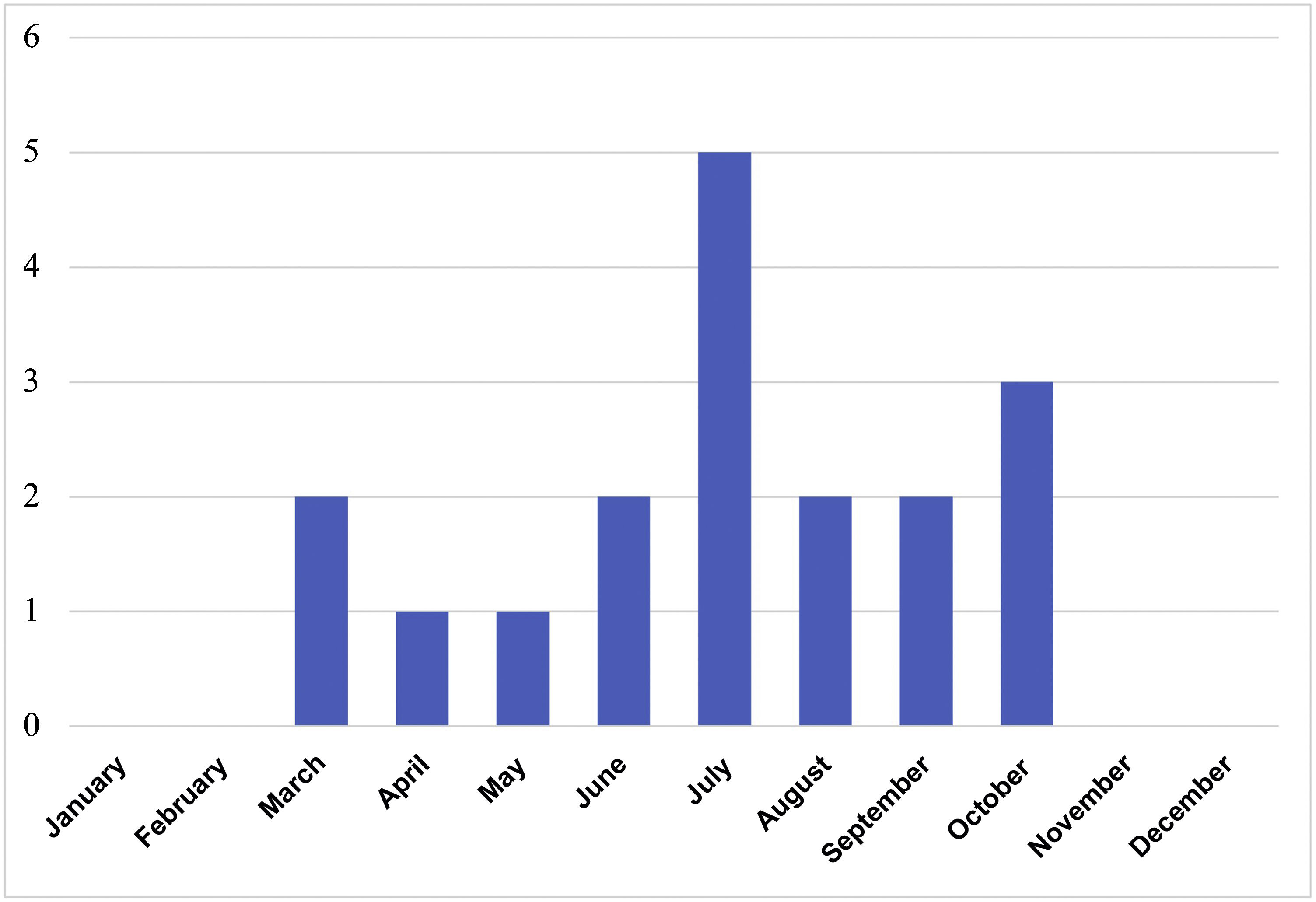

ResultsIn total, 76 serology tests were ordered for 59 patients; of these, 29 were positive in 20 different patients. LB was suspected in 21 patients, 18 of which were diagnosed (50% female; median age 6.4 years, IQR 4.8–11.2). Contact with ticks was reported in 61.1% and possible contact in 27.8%. A median of 2 cases/year (IQR 0–4) was recorded, with a peak of 7 cases in 2015. All occurred between May and October (Fig. 1). The three remaining patients were considered to be false positives of the serology testing. The characteristics of the 21 patients are shown in Table 1.

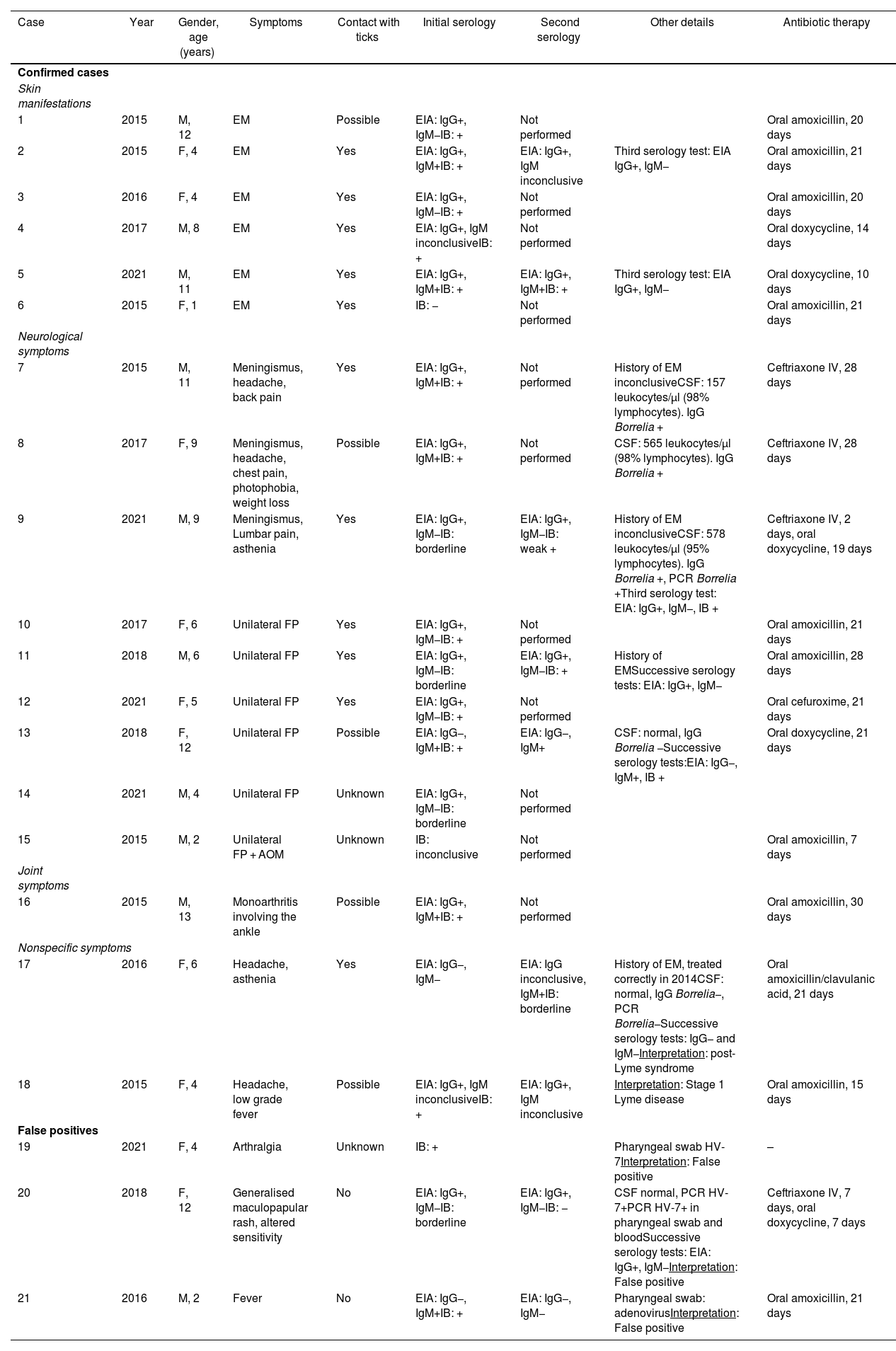

Epidemiological, clinical, laboratory and treatment characteristics of the 21 patients studied with Lyme borreliosis.

| Case | Year | Gender, age (years) | Symptoms | Contact with ticks | Initial serology | Second serology | Other details | Antibiotic therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed cases | ||||||||

| Skin manifestations | ||||||||

| 1 | 2015 | M, 12 | EM | Possible | EIA: IgG+, IgM−IB: + | Not performed | Oral amoxicillin, 20 days | |

| 2 | 2015 | F, 4 | EM | Yes | EIA: IgG+, IgM+IB: + | EIA: IgG+, IgM inconclusive | Third serology test: EIA IgG+, IgM− | Oral amoxicillin, 21 days |

| 3 | 2016 | F, 4 | EM | Yes | EIA: IgG+, IgM−IB: + | Not performed | Oral amoxicillin, 20 days | |

| 4 | 2017 | M, 8 | EM | Yes | EIA: IgG+, IgM inconclusiveIB: + | Not performed | Oral doxycycline, 14 days | |

| 5 | 2021 | M, 11 | EM | Yes | EIA: IgG+, IgM+IB: + | EIA: IgG+, IgM+IB: + | Third serology test: EIA IgG+, IgM− | Oral doxycycline, 10 days |

| 6 | 2015 | F, 1 | EM | Yes | IB: − | Not performed | Oral amoxicillin, 21 days | |

| Neurological symptoms | ||||||||

| 7 | 2015 | M, 11 | Meningismus, headache, back pain | Yes | EIA: IgG+, IgM+IB: + | Not performed | History of EM inconclusiveCSF: 157 leukocytes/µl (98% lymphocytes). IgG Borrelia + | Ceftriaxone IV, 28 days |

| 8 | 2017 | F, 9 | Meningismus, headache, chest pain, photophobia, weight loss | Possible | EIA: IgG+, IgM+IB: + | Not performed | CSF: 565 leukocytes/µl (98% lymphocytes). IgG Borrelia + | Ceftriaxone IV, 28 days |

| 9 | 2021 | M, 9 | Meningismus, Lumbar pain, asthenia | Yes | EIA: IgG+, IgM−IB: borderline | EIA: IgG+, IgM−IB: weak + | History of EM inconclusiveCSF: 578 leukocytes/µl (95% lymphocytes). IgG Borrelia +, PCR Borrelia +Third serology test: EIA: IgG+, IgM−, IB + | Ceftriaxone IV, 2 days, oral doxycycline, 19 days |

| 10 | 2017 | F, 6 | Unilateral FP | Yes | EIA: IgG+, IgM−IB: + | Not performed | Oral amoxicillin, 21 days | |

| 11 | 2018 | M, 6 | Unilateral FP | Yes | EIA: IgG+, IgM−IB: borderline | EIA: IgG+, IgM−IB: + | History of EMSuccessive serology tests: EIA: IgG+, IgM− | Oral amoxicillin, 28 days |

| 12 | 2021 | F, 5 | Unilateral FP | Yes | EIA: IgG+, IgM−IB: + | Not performed | Oral cefuroxime, 21 days | |

| 13 | 2018 | F, 12 | Unilateral FP | Possible | EIA: IgG−, IgM+IB: + | EIA: IgG−, IgM+ | CSF: normal, IgG Borrelia −Successive serology tests:EIA: IgG−, IgM+, IB + | Oral doxycycline, 21 days |

| 14 | 2021 | M, 4 | Unilateral FP | Unknown | EIA: IgG+, IgM−IB: borderline | Not performed | ||

| 15 | 2015 | M, 2 | Unilateral FP + AOM | Unknown | IB: inconclusive | Not performed | Oral amoxicillin, 7 days | |

| Joint symptoms | ||||||||

| 16 | 2015 | M, 13 | Monoarthritis involving the ankle | Possible | EIA: IgG+, IgM+IB: + | Not performed | Oral amoxicillin, 30 days | |

| Nonspecific symptoms | ||||||||

| 17 | 2016 | F, 6 | Headache, asthenia | Yes | EIA: IgG−, IgM− | EIA: IgG inconclusive, IgM+IB: borderline | History of EM, treated correctly in 2014CSF: normal, IgG Borrelia−, PCR Borrelia−Successive serology tests: IgG− and IgM−Interpretation: post-Lyme syndrome | Oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 21 days |

| 18 | 2015 | F, 4 | Headache, low grade fever | Possible | EIA: IgG+, IgM inconclusiveIB: + | EIA: IgG+, IgM inconclusive | Interpretation: Stage 1 Lyme disease | Oral amoxicillin, 15 days |

| False positives | ||||||||

| 19 | 2021 | F, 4 | Arthralgia | Unknown | IB: + | Pharyngeal swab HV-7Interpretation: False positive | – | |

| 20 | 2018 | F, 12 | Generalised maculopapular rash, altered sensitivity | No | EIA: IgG+, IgM−IB: borderline | EIA: IgG+, IgM−IB: − | CSF normal, PCR HV-7+PCR HV-7+ in pharyngeal swab and bloodSuccessive serology tests: EIA: IgG+, IgM−Interpretation: False positive | Ceftriaxone IV, 7 days, oral doxycycline, 7 days |

| 21 | 2016 | M, 2 | Fever | No | EIA: IgG−, IgM+IB: + | EIA: IgG−, IgM− | Pharyngeal swab: adenovirusInterpretation: False positive | Oral amoxicillin, 21 days |

AOM: acute otitis media; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; EIA: enzyme immunoassay; EM: erythema migrans; F: female; FP: facial paralysis; HV: herpes virus; IB: immunoblot; IV: intravenous; M: male; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

In the 18 patients with LB, the most common manifestations were neurological (three patients with back stiffness and associated pain, with confirmed meningitis; six with facial paralysis), followed by dermatological (six with erythema migrans). One patient was seen for monoarthritis involving the ankle, while two patients exhibited nonspecific signs and symptoms: one case of early disseminated LB and one post-Lyme syndrome. The median duration of signs and symptoms prior to consultation was four days (IQR 1–15).

More than one serological study was ordered in seven patients (38.9%). The serological studies were confirmatory in 15 cases (83.3%): 5/6 patients with erythema migrans, 3/3 with meningitis, 4/6 with facial paralysis, 1/1 con arthritis and 2/2 with nonspecific signs and symptoms.

Antibiotic therapy was administered in 94.4% of cases, with a median duration of 21 days (IQR 17.5–24.5). Amoxicillin was prescribed in 70% of patients under eight years of age, and doxycycline in 50% of patients aged eight years or over. The outcome of all patients was satisfactory and no long-term sequelae were detected.

DiscussionIn total, 21 paediatric cases of suspected and/or confirmed LB were identified in Asturias, an endemic region for Borrelia spp. This study provides a better understanding of the clinical spectrum of LB in the child population, the difficulties of microbiological diagnosis and the treatment options available.

While other studies have reported an increasing annual incidence,2 no such increase was observed in this review. Most consultations took place in the summer, consistent with the period of greatest activity of Ixodes ricinus.5 Contact with ticks was known or possible in most cases, but in some cases no targeted medical history was taken. It is important to consider the epidemiological history in order to guide testing, particularly in endemic areas.3

Neurological symptoms were the most common reason for consultation. This could be explained by the greater prevalence of Borrelia garinii in the region, which is associated with neurological symptoms.8 Moreover, neck and ear bites are particularly prevalent in the paediatric population.7 Because these areas are close to the central nervous system, they are associated with manifestations such as meningitis and facial paralysis, unlike in the adult population, in which radiculitis is the primary symptom.9 Given its frequency, it is important to rule out LB in a patient presenting with facial paralysis in an endemic area.7,8 Neuroborreliosis is the most useful indicator for performing epidemiological monitoring of LB in Europe as it is the most common severe manifestation and has well-established diagnostic criteria.10

Erythema migrans is the earliest lesion to appear; it is specific and does not require serological confirmation.5,11,12 In this series, serology testing was performed for all patients and was confirmatory in five cases. Other uncommon cases of LB have been reported, such as arthritis, which is more common in the USA,5 or post-Lyme syndrome with persistent symptoms after appropriate antibiotic therapy, which does not benefit from repeated or prolonged treatments.5 As this series highlights, serological diagnosis presents certain challenges: the onset of early clinical manifestations during a 2 to 4-week time frame until antibody detection (case 6), low yield of IgM in early stages (cases 1, 3 and 4), the need for seroconversion studies in inconclusive cases (cases 9 and 11), the possibility of terminating IgG production following early treatment (cases 13 and 17) and the possibility of cross-reactions with other agents or immunological processes (cases 19, 20 and 21).3 In addition, a positive serology result does not distinguish between active, past or contact disease.5

Compatible symptoms, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis and proven intrathecal production of IgG against Borrelia spp. compared to serum and CSF levels are required for confirmatory diagnosis of neuroborreliosis.5,9,10 IgG against Borrelia spp. in CSF was confirmed in the three cases of meningitis described, with diagnosis by polymerase chain reaction in one case. Its sensitivity to Borrelia spp. is low and variable, just 22.5% in CSF.4 Performing a lumbar puncture in cases of isolated facial paralysis is subject to debate, although a frequent association between facial paralysis and meningitis has been described.9

The antibiotics were chosen in accordance with international recommendations – second-generation tetracyclines or beta-lactams such as amoxicillin – although they were administered for longer than recommended.12 Tetracyclines are not recommended in children under the age of 8 years as tooth enamel can be affected, an effect not seen with second-generation tetracyclines such as doxycycline, which can be used for short periods.5 No complications or sequelae were observed in this series. LB prognosis is better in children than in adults.7,9

The limitations of this study include the short study period, which prevents conclusions being drawn about the evolution of its incidence, and the fact that it was conducted in a hospital setting, which probably underestimates the number of mild cases. As it was a retrospective study, the tick attachment time, associated with the risk of disease transmission, was not recorded.7 The strengths of this study include the fact that it was a study carried out exclusively in the paediatric population and in a region with a high prevalence of infected ticks. Presenting cases with a final interpretation of serology testing false positives helps to underline the difficulties faced when diagnosing LB and the uncertainty clinicians experience when starting treatment.3

FundingNo funding of any kind was received for conducting this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.