To estimate the prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in Navarra, Spain, as well as to distinguish between diagnosed and undiagnosed infections.

MethodsA study was conducted on patients scheduled for surgery unrelated to HCV infection. They were all tested for HCV antibodies, under a routine scheme, from January 2014 to September 2016. Patients with a positive result by enzyme immunoassay were confirmed using immunoblot and/or HCV-RNA. Previous laboratory results were also taken into account. The prevalence was adjusted to the sex and age structure of the Navarra population.

ResultsThe study included a total of 7378 patients with a median age 46 years, of whom 50% women. HCV antibodies were detected in 69 patients, which is a prevalence in the population of 0.83% (95% confidence interval: 0.64–1.05), and was higher in men (1.11%) than in women (0.56%; p=0.0102). Among the HCV positive patients, 67 (97%) had had another previous positive result. Population prevalence of previous positive HCV was 0.80%, and was 0.03% for a new diagnosis. Of the HCV positive patients, 78% had detectable HCV-RNA. It was estimated that 0.65% of the population had had detectable HCV-RNA, and 0.51% continued to have it when recruited into the study.

ConclusionPrevious estimates of prevalence of HCV infection should be revised downwards. Only a small proportion of HCV positive patients remain undiagnosed, and only a small part have active infection.

Estimar la prevalencia de infección por el virus de la hepatitis C (VHC) en Navarra, distinguiendo entre infecciones diagnosticadas y no diagnosticadas.

MétodosSe estudiaron pacientes con cirugía programada no relacionada con la infección por VHC, a los que se les realizó de forma sistemática la determinación de anticuerpos del VHC entre enero de 2014 y septiembre de 2016. En los pacientes con enzimoinmunoanálisis positivo se confirmó el diagnóstico mediante inmunoblot y/o determinación de ARN-VHC. También se comprobó la existencia de resultados positivos previos. La prevalencia se estandarizó por sexo y edad a la población de Navarra.

ResultadosSe analizaron 7.378 pacientes, 50% mujeres, con una mediana de edad de 46 años. En 69 se detectaron anticuerpos del VHC, lo que supone una prevalencia poblacional estimada de 0,83% (intervalo de confianza del 95%: 0,64-1,05), mayor en hombres (1,11%) que en mujeres (0,56%; p=0,0102). Entre los que resultaron anti-VHC positivos, 67 (97%) habían tenido alguna prueba positiva previa. La prevalencia poblacional de diagnóstico previo de anti-VHC fue del 0,80%, y la de nuevos diagnósticos, del 0,03%. El 78% de los pacientes con anti-VHC positivo habían presentado alguna determinación de ARN-VHC detectable. Se estima que el 0,65% de la población había tenido ARN-VHC detectable y el 0,51% lo seguía teniendo en el momento del estudio.

ConclusiónEstos resultados revisan a la baja las estimaciones previas de prevalencia de infección por VHC. Una proporción mínima de las personas con anti-VHC permanecen sin diagnosticar, y solo una parte mantienen infección activa.

Numerous studies have revealed the elevated prevalence of antibodies to the hepatitis C virus (HCV) in different population groups in Spain, with the highest incidence of infections occurring in the 1980s and 1990s.1 Without treatment, 55–85% of infected individuals will develop a chronic infection.2–4 This explains why HCV is a leading cause of burden of disease in Spain.5

The introduction of new direct-acting antiviral drugs for HCV has increased the relevance for making available updated estimates about the actual extent of this infection in the population.3,4 Epidemiological surveillance information about HCV infection is scarce and does not allow for a good understanding of its current prevalence.3,6 Several seroepidemiological surveys have provided estimates, but these are expensive studies, which are difficult to repeat. With the passage of time, they have become partially out-of-date, and often they do not allow for the distinction between diagnosed and undiagnosed infections.7–11 Numerous studies on prevalence in high-risk populations have also been carried out, which are very useful for conducting specific interventions in these groups. However, it is not easy to extrapolate data about the general population from these results.1

The objective of this study was to estimate the total prevalence of HCV infection in the population of Navarra, distinguishing between previously diagnosed and undiagnosed infections, and, additionally, to estimate the prevalence of active infections.

MethodologyA cross-sectional study was carried out on prevalence in the resident population of Navarra covered by the public healthcare network (97% of the total population), using healthcare and Microbiology databases.

In 2014 and 2015, an average of 3.5 HCV antibody tests per year per 100 inhabitants of Navarra was conducted. One part of these tests was carried out in people with some degree of suspicion of HCV infection, and the other part was carried out through systematic screening protocols or routines, without taking into account the results of previous lab tests. In this second group, blood and organ donors were included, as well as pregnant women, couples in assisted reproduction programmes, and patients scheduled for surgery with a high likelihood of bleeding. From all these groups, patients scheduled for interventions in the Maxillofacial Surgery, Plastic Surgery, Otorhinolaryngology, Ophthalmology and Cardiac Surgery units were selected for this study, as they were considered to be the most representative of the general population and least biased with respect to the likelihood of them being infected with HCV.

In the pre-operative assessment of these patients, serological tests for anti-HCV antibodies by microparticle enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (ARCHITECT Anti-HCV, Abbott Laboratories, Wiesbaden, Germany), were systematically requested, along with other tests, without taking into account possible previous serological results.

Anti-HCV positive results from the EIA were confirmed by immunoblotting (INNO-LIA HCV Score INNOGENETICS, Fujirebio, Ghent, Belgium), and/or the quantitative HCV-RNA (RT-PCR) test (Cobas HCV, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

For this study, all patients resident in Navarra for whom pre-operative tests had been requested through the aforementioned units between January 2014 and September 2016 taken from the Microbiology databases, were evaluated. Each patient was included only once, with the last valid result being prioritised.

The existence of positive results for HCV in the medical history and in the Microbiology records was checked for all patients.

Definitions- -

HCV Infection: a patient who tested positive using EIA for anti-HCV antibodies, and with a positive immunoblot and/or with previous or current HCV-RNA detected. Among the HCV infections, two groups were distinguished: diagnosed infections and new diagnoses.

- -

Known or diagnosed HCV infection: a patient with HCV infection for whom there was a previous positive HCV result documented in the Microbiology records or in his/her medical history. This category also included patients who did not have a valid serum sample from the pre-operative lab tests, but who did have a previously documented and confirmed HCV infection. These patients were considered indicators for known infections in the population.

- -

New diagnoses of HCV infection: patients with an HCV infection that was confirmed by the pre-operative lab tests, and for whom a previously documented positive result was not found. These patients were considered indicators for undiagnosed infections in the population.

- -

Current or previous active HCV infection: patients with a confirmed HCV infection and with detectable levels of HCV-RNA at the time of screening or from a prior test.

- -

Active HCV infection at the time of selection: patients with a confirmed HCV infection and with detectable levels of HCV-RNA at the time of screening.

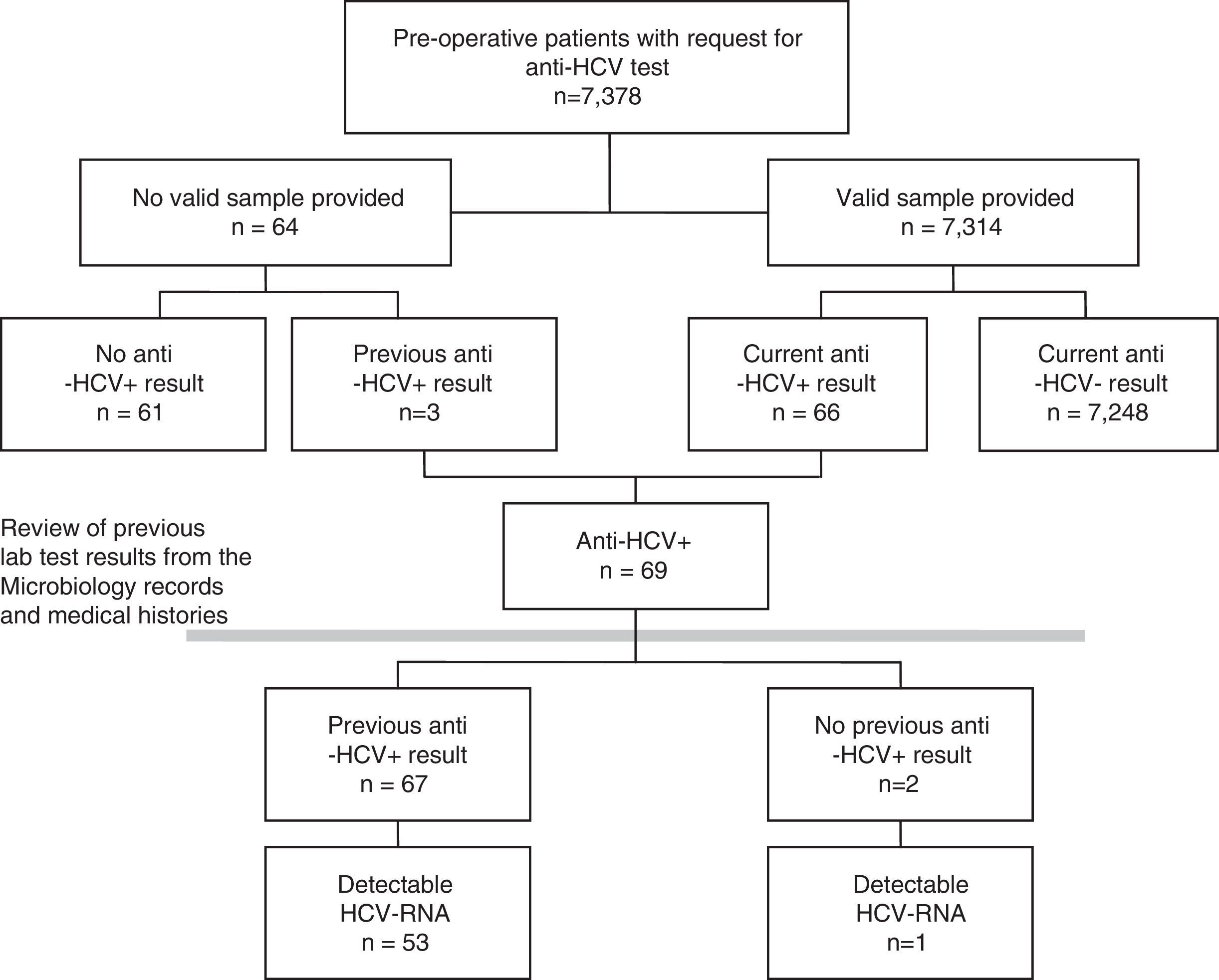

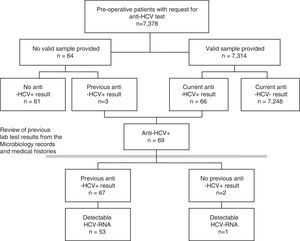

As a first step, the prevalence of each indicator for the total population included in the pre-operative study was calculated. A few patients for whom the pre-operative study was requested did not provide any valid samples. To minimise possible non-participation bias, these patients were also included in the study, the results being taken from their previously documented tests for HCV (Fig. 1). A sensitivity analysis was also carried out, estimating the prevalence in only those patients with a valid result for the pre-operative lab tests.

In the next step, the population prevalence was estimated from the pre-operative population. Since the distribution by age and gender of the patients included in the study may not correspond to that of the general population, the ratios were adjusted with the direct method, taking as a reference the resident population of Navarra with healthcare covered by the Navarra Health Service on 1 January 2016.

To compare the proportions, the Chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test were used. For estimates of prevalence, 95% confidence intervals (CI) were obtained with the mid-p test method.

ResultsBetween January 2014 and September 2016, HCV serology was requested from 7378 pre-operative patients. A valid serum sample was obtained for 7314 (99.1%) patients, no sample was received by the laboratory for 62 and 2 of the samples were not valid (Fig. 1). Forty-two per cent (42%) of patients were from Otorhinolaryngology, 31% from Maxillofacial Surgery, 16% from Plastic Surgery, 6% from Ophthalmology and 6% from Cardiac Surgery. Fifty per cent (50%) were women, and the median age was 46 years (interquartile range 33–61, range 1–100 years).

Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in pre-operative patientsOf the 7314 pre-operative patients with valid lab tests, 89 tested positive in a first EIA, and, from these, 23 were ruled out and 66 tested positive for anti-HCV in a confirmatory test (0.90%). Among the 64 patients who did not provide a valid sample, 3 (4.69%) had previously tested positive for anti-HCV. This implies a prevalence greater than that shown by those analysed (p=0.0217), for which reason it was decided to include them in the prevalence study (Fig. 1).

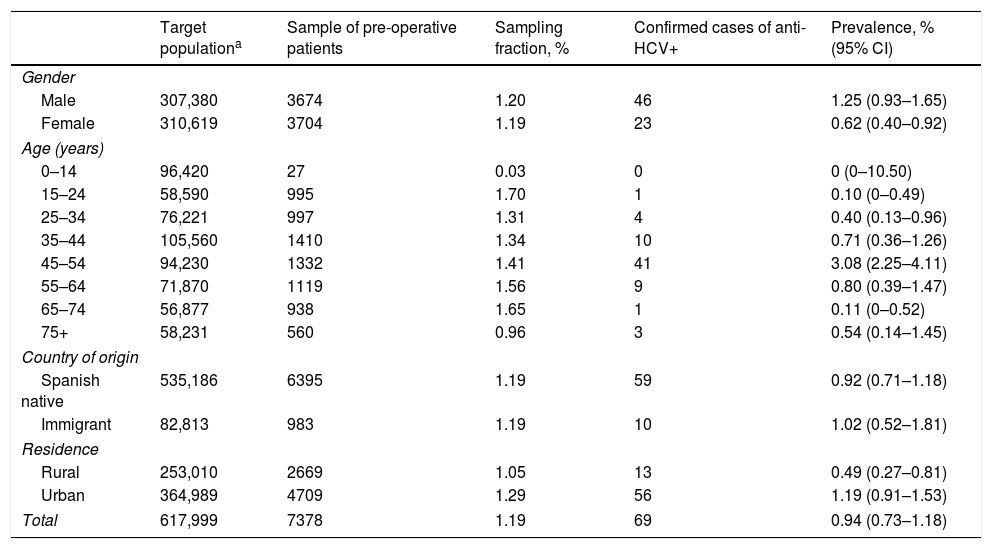

The sample analysed accounted for 1.19% of the entire population covered by the Navarra Health Service. The sampling fraction was just 0.03% of children under 15 years, and 0.96% of people aged 75 or over. In the rest of the age groups, it ranged between 1.31 and 1.70%. The sampling fraction was similar in the Spanish native and immigrant populations, and slightly higher in the urban than in the rural population (Table 1).

Sampling fraction of the sample of pre-operative patients regarding the population covered by the Navarra Health Service, and estimate of the prevalence of positive antibodies to the hepatitis C virus in pre-operative patients by gender, age group, country of origin and residence.

| Target populationa | Sample of pre-operative patients | Sampling fraction, % | Confirmed cases of anti-HCV+ | Prevalence, % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 307,380 | 3674 | 1.20 | 46 | 1.25 (0.93–1.65) |

| Female | 310,619 | 3704 | 1.19 | 23 | 0.62 (0.40–0.92) |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 0–14 | 96,420 | 27 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 (0–10.50) |

| 15–24 | 58,590 | 995 | 1.70 | 1 | 0.10 (0–0.49) |

| 25–34 | 76,221 | 997 | 1.31 | 4 | 0.40 (0.13–0.96) |

| 35–44 | 105,560 | 1410 | 1.34 | 10 | 0.71 (0.36–1.26) |

| 45–54 | 94,230 | 1332 | 1.41 | 41 | 3.08 (2.25–4.11) |

| 55–64 | 71,870 | 1119 | 1.56 | 9 | 0.80 (0.39–1.47) |

| 65–74 | 56,877 | 938 | 1.65 | 1 | 0.11 (0–0.52) |

| 75+ | 58,231 | 560 | 0.96 | 3 | 0.54 (0.14–1.45) |

| Country of origin | |||||

| Spanish native | 535,186 | 6395 | 1.19 | 59 | 0.92 (0.71–1.18) |

| Immigrant | 82,813 | 983 | 1.19 | 10 | 1.02 (0.52–1.81) |

| Residence | |||||

| Rural | 253,010 | 2669 | 1.05 | 13 | 0.49 (0.27–0.81) |

| Urban | 364,989 | 4709 | 1.29 | 56 | 1.19 (0.91–1.53) |

| Total | 617,999 | 7378 | 1.19 | 69 | 0.94 (0.73–1.18) |

Anti-HCV: antibodies to the Hepatitis C virus; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

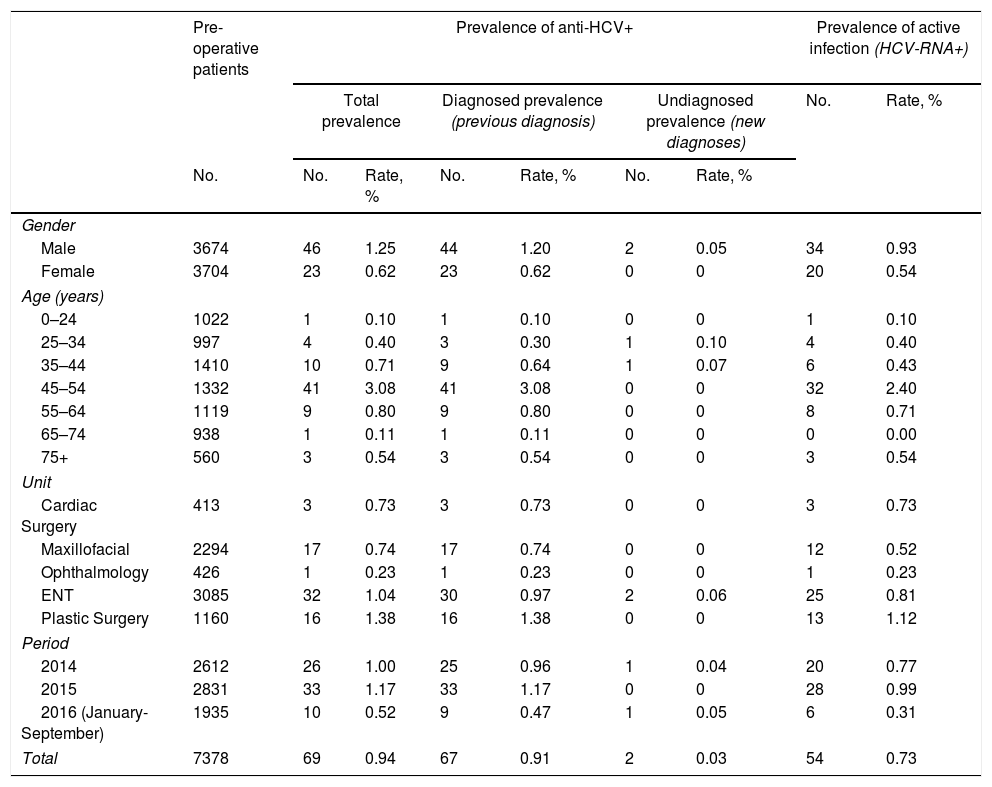

From the total number of pre-operative patients, the prevalence of anti-HCV was 0.94%. It was greater in men (1.25%) than in women (0.62%; p=0.0049). The highest prevalence was observed in the 45–54 age group (3.08%; p<0.0001). No statistically significant differences were found among the surgical units selected (p=0.1847) (Table 2).

Prevalence of positive antibodies to the hepatitis C virus in pre-operative patients, differentiated between prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed infection, and active infection with positive hepatitis C virus RNA detected.

| Pre-operative patients | Prevalence of anti-HCV+ | Prevalence of active infection (HCV-RNA+) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total prevalence | Diagnosed prevalence (previous diagnosis) | Undiagnosed prevalence (new diagnoses) | No. | Rate, % | |||||

| No. | No. | Rate, % | No. | Rate, % | No. | Rate, % | |||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 3674 | 46 | 1.25 | 44 | 1.20 | 2 | 0.05 | 34 | 0.93 |

| Female | 3704 | 23 | 0.62 | 23 | 0.62 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0.54 |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 0–24 | 1022 | 1 | 0.10 | 1 | 0.10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.10 |

| 25–34 | 997 | 4 | 0.40 | 3 | 0.30 | 1 | 0.10 | 4 | 0.40 |

| 35–44 | 1410 | 10 | 0.71 | 9 | 0.64 | 1 | 0.07 | 6 | 0.43 |

| 45–54 | 1332 | 41 | 3.08 | 41 | 3.08 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 2.40 |

| 55–64 | 1119 | 9 | 0.80 | 9 | 0.80 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0.71 |

| 65–74 | 938 | 1 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 75+ | 560 | 3 | 0.54 | 3 | 0.54 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.54 |

| Unit | |||||||||

| Cardiac Surgery | 413 | 3 | 0.73 | 3 | 0.73 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.73 |

| Maxillofacial | 2294 | 17 | 0.74 | 17 | 0.74 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0.52 |

| Ophthalmology | 426 | 1 | 0.23 | 1 | 0.23 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.23 |

| ENT | 3085 | 32 | 1.04 | 30 | 0.97 | 2 | 0.06 | 25 | 0.81 |

| Plastic Surgery | 1160 | 16 | 1.38 | 16 | 1.38 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 1.12 |

| Period | |||||||||

| 2014 | 2612 | 26 | 1.00 | 25 | 0.96 | 1 | 0.04 | 20 | 0.77 |

| 2015 | 2831 | 33 | 1.17 | 33 | 1.17 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 0.99 |

| 2016 (January-September) | 1935 | 10 | 0.52 | 9 | 0.47 | 1 | 0.05 | 6 | 0.31 |

| Total | 7378 | 69 | 0.94 | 67 | 0.91 | 2 | 0.03 | 54 | 0.73 |

Anti-HCV: antibodies to the hepatitis C virus; ENT: otorhinolaryngology; HCV-RNA+: positive detection of hepatitis C virus RNA; indicative of active infection.

Of the 69 patients who were anti-HCV positive, 67 (97%) had a previous positive test result. This number did not vary between men (96%) and women (100%; p=0.5490). These data result in a prevalence of known infections of 0.91%, which was greater in men (1.20%) than in women (0.62%; p=0.0090), and in the 45–54 age group (3.08%; p<0.0001) with respect to the other age groups.

The 2 patients who tested positive for anti-HCV for the first time resulted in a prevalence of undiagnosed seropositivity of 0.03%, with no significant difference between the genders (p=0.2479) nor between age groups (Table 2).

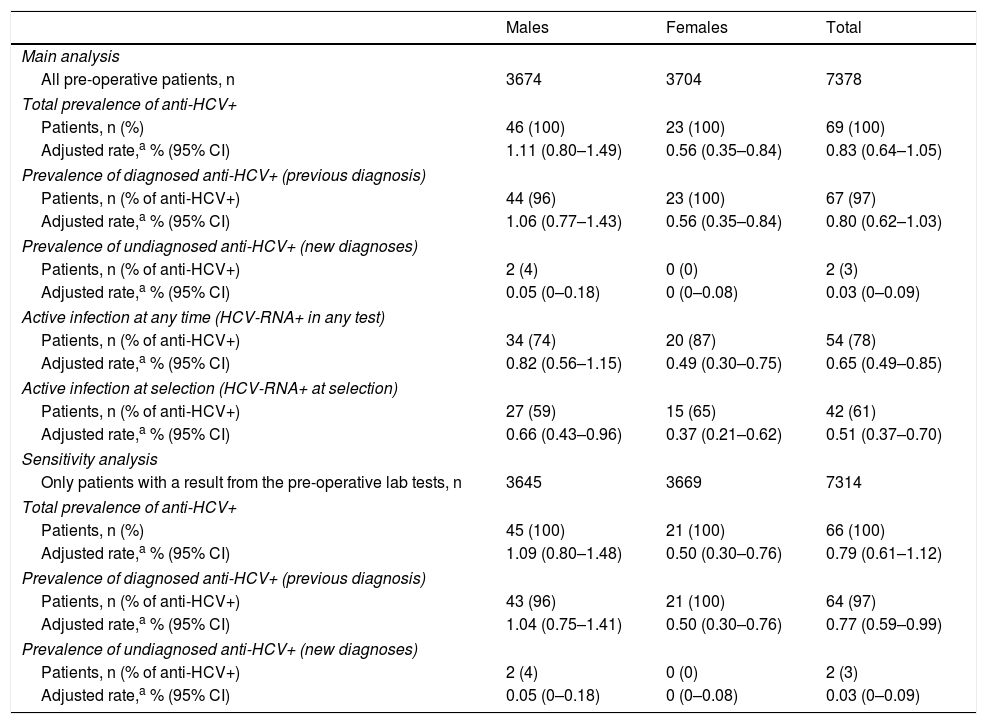

Estimates of prevalence of HCV infection in the populationWith the aim of estimating the prevalence of HCV antibodies in the population, the figures obtained from the 7378 patients included in the study were adjusted by gender and age according to the population structure of Navarra. The rate of prevalence estimated for the whole population was 0.83% (95% CI 0.64–1.05), and was greater in men than in women: 1.11 and 0.56%, respectively (p=0.0102) (Table 3).

Estimates of the prevalence of antibodies and hepatitis C virus RNA for the population of Navarra from the sample of pre-operative patients.

| Males | Females | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main analysis | |||

| All pre-operative patients, n | 3674 | 3704 | 7378 |

| Total prevalence of anti-HCV+ | |||

| Patients, n (%) | 46 (100) | 23 (100) | 69 (100) |

| Adjusted rate,a % (95% CI) | 1.11 (0.80–1.49) | 0.56 (0.35–0.84) | 0.83 (0.64–1.05) |

| Prevalence of diagnosed anti-HCV+ (previous diagnosis) | |||

| Patients, n (% of anti-HCV+) | 44 (96) | 23 (100) | 67 (97) |

| Adjusted rate,a % (95% CI) | 1.06 (0.77–1.43) | 0.56 (0.35–0.84) | 0.80 (0.62–1.03) |

| Prevalence of undiagnosed anti-HCV+ (new diagnoses) | |||

| Patients, n (% of anti-HCV+) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) |

| Adjusted rate,a % (95% CI) | 0.05 (0–0.18) | 0 (0–0.08) | 0.03 (0–0.09) |

| Active infection at any time (HCV-RNA+ in any test) | |||

| Patients, n (% of anti-HCV+) | 34 (74) | 20 (87) | 54 (78) |

| Adjusted rate,a % (95% CI) | 0.82 (0.56–1.15) | 0.49 (0.30–0.75) | 0.65 (0.49–0.85) |

| Active infection at selection (HCV-RNA+ at selection) | |||

| Patients, n (% of anti-HCV+) | 27 (59) | 15 (65) | 42 (61) |

| Adjusted rate,a % (95% CI) | 0.66 (0.43–0.96) | 0.37 (0.21–0.62) | 0.51 (0.37–0.70) |

| Sensitivity analysis | |||

| Only patients with a result from the pre-operative lab tests, n | 3645 | 3669 | 7314 |

| Total prevalence of anti-HCV+ | |||

| Patients, n (%) | 45 (100) | 21 (100) | 66 (100) |

| Adjusted rate,a % (95% CI) | 1.09 (0.80–1.48) | 0.50 (0.30–0.76) | 0.79 (0.61–1.12) |

| Prevalence of diagnosed anti-HCV+ (previous diagnosis) | |||

| Patients, n (% of anti-HCV+) | 43 (96) | 21 (100) | 64 (97) |

| Adjusted rate,a % (95% CI) | 1.04 (0.75–1.41) | 0.50 (0.30–0.76) | 0.77 (0.59–0.99) |

| Prevalence of undiagnosed anti-HCV+ (new diagnoses) | |||

| Patients, n (% of anti-HCV+) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) |

| Adjusted rate,a % (95% CI) | 0.05 (0–0.18) | 0 (0–0.08) | 0.03 (0–0.09) |

Anti-HCV: antibodies to the hepatitis C virus; HCV-RNA+: positive detection of hepatitis C virus RNA; indicative of active infection; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

The 67 patients who had previously tested positive made it possible to obtain a population prevalence estimate for known infection of 0.80%, greater in men (1.06%) than in women (0.56%; p=0.0188). The 2 patients who tested positive for HCV for the first time resulted in a population prevalence for undiagnosed infection in the population of 0.03%, with no difference between the genders (Table 3). Taking into account only the population aged over 15, prevalence rose to 0.97% (95% CI 0.76–1.22).

The sensitivity analysis including only those patients with a valid result from the pre-operative lab tests provided slightly lower estimates of prevalence (Table 3).

Estimate of prevalence of active infectionOf the 69 patients who tested positive for anti-HCV, in 54 (78%) HCV-RNA had been detected, which resulted in a prevalence of active infection (in a current or previous test) in the population of 0.65% (95% CI 0.49–0.85). This rate was 0.82% for men and 0.49% for women (p=0.0774). At the time of the pre-operative lab tests, HCV-RNA was detected in only 42 patients, which involved 61% of those who tested positive for anti-HCV and a population prevalence of active infection at the time of the study of 0.51% (95% CI 0.37–0.70) (Table 3). In the remaining 12 patients, the HCV-RNA had become negative at the time of the pre-operative study, after they had previously received antiviral treatment.

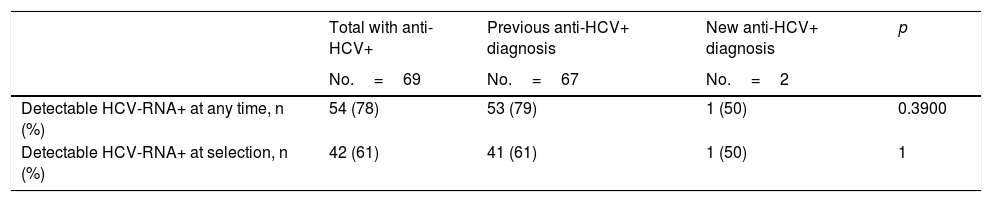

Among the patients who had had a previous anti-HCV diagnosis, these percentages were 79 and 61%, respectively. Conversely, only one of the 2 patients diagnosed with anti-HCV for the first time during the pre-surgical study had detectable levels of HCV-RNA (Table 4).

Results from the hepatitis C virus RNA test among patients with current or previously detected positive antibodies.

| Total with anti-HCV+ | Previous anti-HCV+ diagnosis | New anti-HCV+ diagnosis | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=69 | No.=67 | No.=2 | ||

| Detectable HCV-RNA+ at any time, n (%) | 54 (78) | 53 (79) | 1 (50) | 0.3900 |

| Detectable HCV-RNA+ at selection, n (%) | 42 (61) | 41 (61) | 1 (50) | 1 |

Anti-HCV: antibodies to the hepatitis C virus; HCV-RNA+: positive detection of hepatitis C virus RNA; indicative of active infection.

The results estimate a prevalence of anti-HCV of 0.83% in the population of Navarra in the period 2014–2016. Ninety-seven per cent (97%) of people who tested positive for anti-HCV had had a previous diagnosis, and just 3% tested positive for anti-HCV for the first time, which indicates a very low number of undiagnosed infections in the population. This prevalence is significantly lower than the last official estimate published for the adult Spanish population (1.7%).3,12 The number of undiagnosed HCV infections that we estimate is also much lower than 60%, which is what had been proposed for Spain.13 The validity of the estimates that we obtained is reinforced by the good representativeness of the sample by gender, age and country of origin with respect to the target population. The estimate of prevalence of diagnosed infections (0.80%) also matches what was calculated from the Microbiology record of the Navarra Health Service in January 2015 (data not published). According to this same source, in the last few years an average of 3.5 HCV serological tests per 100 inhabitants has been carried out in Navarra, which could explain the low number of undiagnosed infections.

The discrepancy between our study and other sources may have some explanations, explained below. To date, a prevalence of anti-HCV in Spain of between 1.6 and 2.6%1 has been estimated, based on studies which were mostly conducted before 2000. For this reason they may be very out-of-date, and many of them are based on a single EIA, without a confirmatory test, which could give rise to a false positive result in populations with a prevalence that is not very high.

Domínguez et al. published results from a population survey conducted in Catalonia in 1996, according to which more than half the infections were concentrated in people born before 1941,7 which suggests that some of them will by now have died. The majority of HCV infections in Spain occurred in the 1980s and at the beginning of the 1990s, and, since then, measures to control transmission have been extended.3 With the progressive ageing of the cohort of people with HCV infections, the prevalence will have declined, as the number of deaths exceeds the number of new infections.14

The seroepidemiological survey carried out in the Community of Madrid in 2008–2009 found a seroprevalence of anti-HCV in the population of 16–80 year-olds of 1.8%.8 The epidemiological differences between regions, the different study periods and the fact that this survey was based on an EIA without a confirmatory test may explain the difference with respect to the prevalence of 0.97% that we found in Navarra for those aged over 15. Another seroepidemiological survey carried out in the Basque Country in 2009 in the population of 2–59-year-olds, this time including only confirmed anti-HCV results, found a prevalence of 0.7%,15 similar to what we found in Navarra for this age range. In healthy workers in Madrid and Murcia analysed between 2007 and 2010, a seroprevalence of anti-HCV of 0.6% was found. Although this is slightly lower than our estimate, the difference can be explained by the bias of the healthy worker.16

In Spain, the number of undiagnosed HCV infections has hardly been studied, and, in the absence of data, it was assumed that it could be as many as those who had been diagnosed.4 In contrast to this, the Basque Country survey found that out of 4 positive cases, in 3 there was a history of HCV infection, which lowered the number of undiagnosed infections to 25%.15 Our results go further, and show that only a small number of the total infections are still currently undiagnosed, which is consistent, given that the majority of infected individuals have more than 25 years of evolution.

Coinciding with previous studies, we found a greater prevalence of anti-HCV in men than in women,1,8 and in the age group of 45–54 (birth cohorts from 1960 to 1969),14 while the prevalence decreases considerably in younger birth cohorts.8 These epidemiological patterns are explained by the mechanisms of transmission of HCV that have predominated in Spain. Through studies on HIV, we know that transmission in injecting drug users affected men and cohorts born between 1950 and 1970 more.17 Transmission by iatrogenic mechanisms, which includes transfusions, blood products and the use of non-disposable or inadequately sterilised materials, has been controlled since the late 1980s, there is little difference in the way it affects the genders and it is a trend that increases with age. Unlike other countries, there is no reason to suspect reactivation of these mechanisms of transmission in recent years, nor the existence of large groups of undiagnosed infected individuals.18–20

Healthcare and epidemiological interest in HCV infection is centred on people with an active infection, as these individuals are the potential transmitters and candidates for antiviral treatment. Seventy-eight per cent (78%) of people who tested positive for anti-HCV had had a viral load detected at some point, although in the pre-operative tests this number dropped to 61%, mostly following antiviral treatment.

The similarity in estimates between the age groups we obtained in Navarra and those from the Basque Country survey support the fact that these estimates could also be indicative of other autonomous communities. However, the epidemiological information about HIV infection, with common transmission mechanisms, shows a wide variability among autonomous communities, among which Navarra occupies an intermediate position with rates close to the state average.21

This study has some limitations. The population studied may not be representative of the general population with regard to HCV. Although the target population was that covered by the Navarra Health Service, there may be a bias due to the possible use of private healthcare. Serological screening was applied routinely, independently of history of risk and previous test results. The selected population included 1.19% of the total population with a similar distribution by gender and country of origin, and a wide range of ages. The rural population was less represented in the sample and had a lower prevalence than the urban population, which could bias the estimates slightly upwards. The lower representation of children and very elderly people was controlled in the analysis by age adjustment. The types of surgery selected do not raise suspicions of major deviations in the prevalence of anti-HCV, and the inclusion of 5 units will have diminished possible biases inherent to a single unit, although no differences were observed in the prevalence among units. The surveys on population seroprevalence usually include individuals for whom a blood test has been requested, which is not very different to the criteria we used in this study. Other populations, such as blood donors or pregnant women, would have had much more significant deviations with regard to the general population, the first because of the prior questionnaire which excluded people with a known risk, and the second because it only represented young women, which is a group with a particularly low prevalence of HCV.

Screening lasted for 2 years and 9 months, during which time new antiviral treatments were introduced. This could have influenced the prevalence of active infections at the time of selection, but not the prevalence of active infections from previous tests or positive anti-HCVs. No valid pre-operative serum sample was available for 64 patients, and the prevalence of known positivity was higher for these patients than the rest. We were not able to rule out the possibility that another of those patients who were not analysed had an undiagnosed HCV infection. To control possible bias, these patients were included in the main analysis, and we also carried out sensitivity analyses excluding them, confirming that the estimates were not modified much.

There is reason to believe that the new direct-acting antiviral drugs quickly reduce the prevalence of HCV-RNA, by achieving sustained virologic response in the vast majority of those treated.22 At the time of selection, 12 patients from our study already had negative results after previous positive HCV-RNA values following antiviral treatment, which shows that the results of prevalence studies will be increasingly influenced by the impact of treatments.

These results show a prevalence of HCV infection of less than has been estimated in previous studies. It is therefore advisable that the previous prevalence estimates of HCV infection be revised downwards in our setting. The low percentage of undiagnosed infections does not seem to justify a need for increasing the current rate of screening for HCV infection in populations without symptoms, with no elevated transaminases, nor exposure to known risks; but, conversely, testing for anti-HCV should not be omitted in the case of any of these circumstances. Only a decreasing number of infected individuals have an active infection, and these are the potential transmitters and candidates for antiviral treatment. The ageing nature of the infected population and the rapid spread of new antiviral treatments is changing the epidemiological situation for HCV infection in Spain.

FundingThis study was part of the EIPT-VIH project funded by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality through the Strategic National Plan for Hepatitis C.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Aguinaga A, Díaz-González J, Pérez-García A, Barrado L, Martínez-Baz I, Casado I, et al. Estimación de la prevalencia de infección diagnosticada y no diagnosticada por el virus de la hepatitis C en Navarra, 2014–2016. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:325–331.