Anaerobic Gram-negative bacilli (AGNB) infections are common and can be life-threatening. A rise in the incidence has been reported in recent years, mainly the result of a growing number of patients with increasingly complex diseases and longer life expectancy.1,2 Studies have also detected an increase in the resistance of these bacteria to antimicrobial agents, which can lead to empirical treatments being inadequate.1,3 On that basis, some authors argue the importance not only of systematically performing antibiotic susceptibility tests, but also the need to have antimicrobial resistance monitoring systems.4 The aim of the study was to analyse how the antibiotic susceptibility profiles of the most prevalent AGNB had evolved in the Autonomous Region of Valencia (Valencia) over the last seven years.

The Red de Vigilancia Microbiológica de la Comunidad Valenciana (RedMiVa) [Valencia Microbiological Surveillance Network] was used as the data source. RedMiVa is a pioneering computer application integrated with the General Directorate for Public Health at Valencia's Department of Health which collects and stores the microbiology results from all public Microbiology Services in Valencia on a daily basis. This makes it possible to analyse a large number of cases and has been an important step in improving epidemiological surveillance. We performed a search of the isolates of Bacteroides spp., Prevotella spp., Fusobacterium spp. and Porphyromonas spp. registered in the period 2010–2016. The bacterial isolation and identification procedures and the antimicrobial susceptibility studies were those particular to each laboratory. We considered patients with any of these anaerobic bacteria in blood, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, respiratory, skin or soft tissue samples as “cases”. We did not include duplicate isolates. We analysed variables of time and place, variables of the person and microbiological variables (species detected and antimicrobial susceptibility). The comparison of the frequency distribution of antibiotic susceptibility in the years studied was carried out using Pearson's Chi square test; a value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We detected a total of 10,835 patients with isolation of AGNB: 7139 (66%) with Bacteroides spp.; 2842 (26%) with Prevotella spp.; 685 (6%) with Fusobacterium spp.; and 169 (2%) with Porphyromonas spp. The only significant differences detected were in the comparative study by year in Prevotella spp. and Fusobacterium spp., where there was a progressive increase in the total number of cases over the period. No significant differences were found in the study by gender. The median age of the patients was 67° for Bacteroides, 55° for Prevotella, 53° for Fusobacterium and 57° for Porphyromonas spp. The largest proportion of isolates were found in skin and soft tissue samples (5049, 47%), with gastrointestinal system samples being the next most common (3360, 31%). The main bacterial species detected were: Bacteroides fragilis group (3180; 44%); Prevotella bivia (652; 23%); Fusobacterium nucleatum (247; 36%); and Porphyromonas asaccharolytica (121; 72%).

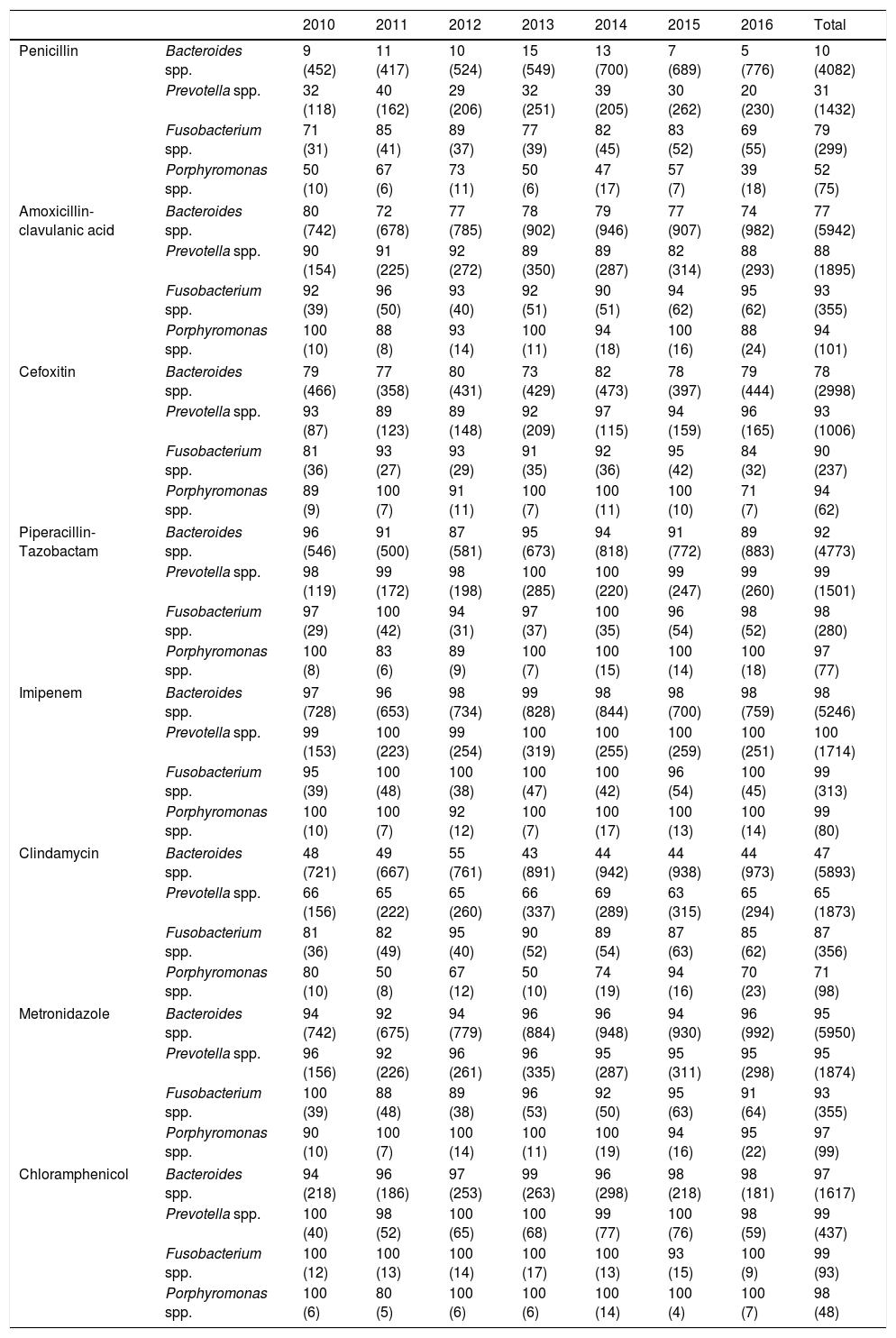

Changes over the study period in the susceptibility to antibiotics of the different genera are shown in Table 1. Penicillin susceptibility rates did not vary significantly during 2010–2014, but did decrease (p<0.05) in the last two years of study (2015–2016), in line with the results of other series.4–6 Sensitivity to amoxicillin–clavulanic acid and cefoxitin remained constant throughout the period.

Percentage of susceptibility and number of isolates (in brackets) of Bacteroides, Prevotella, Fusobacterium and Porphyromonas spp. detected in Valencia (2010–2016).

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillin | Bacteroides spp. | 9 (452) | 11 (417) | 10 (524) | 15 (549) | 13 (700) | 7 (689) | 5 (776) | 10 (4082) |

| Prevotella spp. | 32 (118) | 40 (162) | 29 (206) | 32 (251) | 39 (205) | 30 (262) | 20 (230) | 31 (1432) | |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 71 (31) | 85 (41) | 89 (37) | 77 (39) | 82 (45) | 83 (52) | 69 (55) | 79 (299) | |

| Porphyromonas spp. | 50 (10) | 67 (6) | 73 (11) | 50 (6) | 47 (17) | 57 (7) | 39 (18) | 52 (75) | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | Bacteroides spp. | 80 (742) | 72 (678) | 77 (785) | 78 (902) | 79 (946) | 77 (907) | 74 (982) | 77 (5942) |

| Prevotella spp. | 90 (154) | 91 (225) | 92 (272) | 89 (350) | 89 (287) | 82 (314) | 88 (293) | 88 (1895) | |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 92 (39) | 96 (50) | 93 (40) | 92 (51) | 90 (51) | 94 (62) | 95 (62) | 93 (355) | |

| Porphyromonas spp. | 100 (10) | 88 (8) | 93 (14) | 100 (11) | 94 (18) | 100 (16) | 88 (24) | 94 (101) | |

| Cefoxitin | Bacteroides spp. | 79 (466) | 77 (358) | 80 (431) | 73 (429) | 82 (473) | 78 (397) | 79 (444) | 78 (2998) |

| Prevotella spp. | 93 (87) | 89 (123) | 89 (148) | 92 (209) | 97 (115) | 94 (159) | 96 (165) | 93 (1006) | |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 81 (36) | 93 (27) | 93 (29) | 91 (35) | 92 (36) | 95 (42) | 84 (32) | 90 (237) | |

| Porphyromonas spp. | 89 (9) | 100 (7) | 91 (11) | 100 (7) | 100 (11) | 100 (10) | 71 (7) | 94 (62) | |

| Piperacillin-Tazobactam | Bacteroides spp. | 96 (546) | 91 (500) | 87 (581) | 95 (673) | 94 (818) | 91 (772) | 89 (883) | 92 (4773) |

| Prevotella spp. | 98 (119) | 99 (172) | 98 (198) | 100 (285) | 100 (220) | 99 (247) | 99 (260) | 99 (1501) | |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 97 (29) | 100 (42) | 94 (31) | 97 (37) | 100 (35) | 96 (54) | 98 (52) | 98 (280) | |

| Porphyromonas spp. | 100 (8) | 83 (6) | 89 (9) | 100 (7) | 100 (15) | 100 (14) | 100 (18) | 97 (77) | |

| Imipenem | Bacteroides spp. | 97 (728) | 96 (653) | 98 (734) | 99 (828) | 98 (844) | 98 (700) | 98 (759) | 98 (5246) |

| Prevotella spp. | 99 (153) | 100 (223) | 99 (254) | 100 (319) | 100 (255) | 100 (259) | 100 (251) | 100 (1714) | |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 95 (39) | 100 (48) | 100 (38) | 100 (47) | 100 (42) | 96 (54) | 100 (45) | 99 (313) | |

| Porphyromonas spp. | 100 (10) | 100 (7) | 92 (12) | 100 (7) | 100 (17) | 100 (13) | 100 (14) | 99 (80) | |

| Clindamycin | Bacteroides spp. | 48 (721) | 49 (667) | 55 (761) | 43 (891) | 44 (942) | 44 (938) | 44 (973) | 47 (5893) |

| Prevotella spp. | 66 (156) | 65 (222) | 65 (260) | 66 (337) | 69 (289) | 63 (315) | 65 (294) | 65 (1873) | |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 81 (36) | 82 (49) | 95 (40) | 90 (52) | 89 (54) | 87 (63) | 85 (62) | 87 (356) | |

| Porphyromonas spp. | 80 (10) | 50 (8) | 67 (12) | 50 (10) | 74 (19) | 94 (16) | 70 (23) | 71 (98) | |

| Metronidazole | Bacteroides spp. | 94 (742) | 92 (675) | 94 (779) | 96 (884) | 96 (948) | 94 (930) | 96 (992) | 95 (5950) |

| Prevotella spp. | 96 (156) | 92 (226) | 96 (261) | 96 (335) | 95 (287) | 95 (311) | 95 (298) | 95 (1874) | |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 100 (39) | 88 (48) | 89 (38) | 96 (53) | 92 (50) | 95 (63) | 91 (64) | 93 (355) | |

| Porphyromonas spp. | 90 (10) | 100 (7) | 100 (14) | 100 (11) | 100 (19) | 94 (16) | 95 (22) | 97 (99) | |

| Chloramphenicol | Bacteroides spp. | 94 (218) | 96 (186) | 97 (253) | 99 (263) | 96 (298) | 98 (218) | 98 (181) | 97 (1617) |

| Prevotella spp. | 100 (40) | 98 (52) | 100 (65) | 100 (68) | 99 (77) | 100 (76) | 98 (59) | 99 (437) | |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 100 (12) | 100 (13) | 100 (14) | 100 (17) | 100 (13) | 93 (15) | 100 (9) | 99 (93) | |

| Porphyromonas spp. | 100 (6) | 80 (5) | 100 (6) | 100 (6) | 100 (14) | 100 (4) | 100 (7) | 98 (48) | |

Resistance to piperacillin-tazobactam (highest level of 8% was detected in Bacteroides spp.), imipenem (highest level 2%, in Bacteroides spp.), metronidazole (highest level 7%, in Fusobacterium spp.) and chloramphenicol (highest level 3%, in Bacteroides spp.) was very low or even non-existent, in line with other studies.4,6–10

In contrast with the results reported by other authors, apart from in the case of Fusobacterium spp., the low sensitivity to clindamycin remained constant throughout the period.6,8,9

One of the limitations of this study was the small sample size found for each year in the case of Porphyromonas spp., although, overall, the number of cases analysed was not insignificant.

The susceptibility to antibiotics of the most prevalent AGNB in Valencia has not changed remarkably in recent years. Therefore, we do not believe it is necessary to systematically report the results of susceptibility studies, except in the case of serious infections. However, from the results obtained in this study, we do not recommend using penicillin and clindamycin empirically or, in the case of Bacteroides spp., amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and cefoxitin. We do recommend monitoring of antibiotic resistance patterns, in order to predict future changes in susceptibility to the antimicrobial agents most commonly used in the infections caused by these bacteria, and to help establish appropriate empirical therapies.

Please cite this article as: Gil-Tomás JJ, Jover-García J, Colomina-Rodríguez J. Vigilancia de la sensibilidad antibiótica de anaerobios gramnegativos: RedMiVa 2010–2016. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:200–201.