Campylobacter spp. is the leading cause of bacterial enteritis in industrialized countries, but the literature about its recurrence is scarce. The objective of this study is to analyze a case series of recurrent campylobacteriosis in adult and pediatric patients.

MethodsDuring a two-year period, the demographic, clinical and microbiological data were collected retrospectively from patients who met the clinical criteria of recurrent Campylobacter spp. gastroenteritis. Enteropathogens were identified by a multiplex-PCR gastrointestinal pathogens panel. When Campylobacter spp. was detected, the stool sample was cultured in specific medium and tested for antibiotic susceptibility.

ResultsTwenty-four (2.03%) out of 1180 patients with Campylobacter spp. positive-PCR met the inclusion criteria. Thirteen patients suffered from underlying diseases, and 11 had no known risk factors but they were all pediatric patients. From the 24 patients were documented 70 episodes. One patient had two episodes of bacteremia. Coinfection/co-detection with other enteropathogens was found in 10 patients being Giardia intestinalis the most frequent. Twelve (22.6%) out of 53 isolates were resistant to macrolides. One patient had two isolates of multi-drug resistant C. coli, only susceptible to gentamicin.

ConclusionThe results suggest the presence of underlying diseases in most adult patients with recurrent Campylobacter spp. infections, particularly primary immunodeficiency. Most of the pediatric patients with recurrent campylobacteriosis lack of known risk factors. Concomitant detection with other enteropathogens was common. The resistance to macrolides was much higher as compared with previous reported rates.

La bacteria Campylobacter spp. es la principal causa de enteritis bacteriana en los países industrializados, pero la literatura sobre su recurrencia es escasa. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar una serie de casos de campilobacteriosis recurrente en pacientes adultos y pediátricos.

MétodosDurante un período de dos años se recogieron datos demográficos, clínicos y microbiológicos de forma retrospectiva de pacientes que cumplían los criterios clínicos de gastroenteritis por Campylobacter spp. recurrente. Los enteropatógenos se identificaron mediante un panel de patógenos gastrointestinales por PCR múltiple. Cuando se detectaba Campylobacter spp., la muestra de heces se cultivaba en un medio específico y se sometía a pruebas de susceptibilidad a antibióticos.

ResultadosVeinticuatro (2,03%) de 1.180 pacientes con PCR positiva para Campylobacter spp. cumplieron los criterios de inclusión. Trece pacientes padecían enfermedades subyacentes y 11 no tenían factores de riesgo conocidos, pero en todos los casos eran pacientes pediátricos. De estos 24 pacientes se documentaron 70 episodios. Un paciente presentó dos episodios de bacteriemia. Se observó coinfección/codetección de otros enteropatógenos en 10 pacientes, y el más frecuente fue Giardia intestinalis. Doce (22,6%) de los 53 aislados eran resistentes a los macrólidos. Un paciente presentó dos aislados con Campylobacter coli multirresistente, que solo era susceptible a gentamicina.

ConclusiónLos resultados sugieren la presencia de enfermedades subyacentes en la mayor parte de los pacientes adultos con infecciones por Campylobacter spp. recurrentes, en particular inmunodeficiencia primaria. La mayoría de los pacientes pediátricos con campilobacteriosis recurrente no presentaban factores de riesgo conocidos. Se observó con frecuencia la detección concomitante de otros enteropatógenos. La resistencia a los macrólidos fue muy superior en comparación con las tasas notificadas anteriormente.

Campylobacter spp. is among the most common pathogen in human bacterial invasive gastroenteritis.1 The clinical symptoms of campylobacteriosis in humans are diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea and fever. Complications such as bacteremia are uncommon, even though intestinal carriage is a risk factor for bacteremia in immunocompromised patients.1 The acute phase is followed by sequelae in a small group of patients: Guillain-Barré syndrome and reactive arthritis.2 The transmission chain of Campylobacter spp. is not completely known but poultry is considered the major reservoir for transmission to humans.3Campylobacter spp. infections have increased, over the last 10 years, in both developed and developing countries.4 The majority of reported Campylobacter spp. infections are caused by Campylobacter jejuni (about 90% of cases) and secondly, by Campylobacter coli, which causes 1–25% of Campylobacter-related diarrheal diseases.5 In Spain, as in many other developed countries, the highest rates of campylobacteriosis in both male and female were in children less than 5 years and it decreases with age.6

Patients with underlying diseases, immunocompromised patients included those with hypogammaglobulinemia, and patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection are especially susceptible to Campylobacter spp. infections. These patients occasionally report severe, prolonged and recurrent infections.7 To date, there are few reports about recurrent Campylobacter spp. infection1; however, some publications of case-report identify different causes related to this recrudescence.1,2,7–10 The aim of this study is to summarize the available data involved in recurrent Campylobacter spp. gastroenteritis in a tertiary hospital in Spain and identify groups of high-risk patients.

Material and methodsA retrospective observational cohort study design was conducted. We collected the demographic, clinical and microbiological data of the patients who met the inclusion criteria of recurrent campylobacteriosis. The clinical data were collected from the hospital database, laboratory and primary health care informatics systems. The stool samples were obtained between April 1st 2018 and 31st March 2020 at the Hospital Universitario La Paz (Madrid), from outpatients and inpatients who meet recurrent Campylobacter spp. clinical criteria; defined as ≥2 episodes of clinical gastroenteritis with either positive stool or blood cultures, with a separation of an interval of ≥90 days.1,8 Macroscopic examination of the stool samples was performed at admission and samples with a Bristol Stool Form Scale11 with a score ≥5 were submitted for microbiological testing. Formed stools were only analyzed in patients with clinical suspicion of Ileitis or appendicitis.

All the stool samples collected were analyzed using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the Allplex™ GI-Bacteria (I) Assay (Seegene®) in combination with automated DNA extraction and PCR setup using a Hamilton Microlab STARlet Liquid Handling robot, according to the manufacturer's instructions. This assay includes a total of 7 bacterial targets, including Aeromonas spp., Campylobacter spp., Clostridioides difficile toxin B, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp./EIEC, Vibrio spp. and Yersinia enterocolitica. PCR was considered as the gold standard technique to identify Campylobacter spp. gastroenteritis. Children up to five years old and immunosuppressed patients were also tested for virus (Allplex™ GI-Virus Assay). PCR for protozoa detection (Allplex™ GI-Parasites Assay) were performed in all children up to 14 years old or in any patient at request of the health care provider.

When samples yielded PCR-positive results for Campylobacter spp., the stools were plated onto CCDA Selective Medium agar (Oxoid, ThermoFisher). The plates were incubated at 42°C under microaerophilic conditions (5–10% CO2) for 48h. Suspicious colonies were identified by MALDI-TOF MS Biotyper® (Brucker Daltonics). Antimicrobial susceptibility was tested on Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 5% of horse blood and 20mg/L β-NAD (Biomérieux) by the disk diffusion method. The antibiotics tested routinely were ampicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, erythromycin and ciprofloxacin. Only the strains resistant to all these antibiotics were also tested to tetracycline and gentamicin. The clinical breakpoints used to interpret the susceptibility to erythromycin, ciprofloxacin and tetracycline were obtained according to EUCAST guidelines. Erythromycin was used to determine susceptibility to clarithromycin and azithromycin. The inhibition zone diameter of gentamicin was reported according to EUCAST epidemiological cut-off values. Ampicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was categorized according to the cut-offs proposed by Sifré et al.12

Ethical approval for this study was obtained by the local ethics committee (PI-4476).

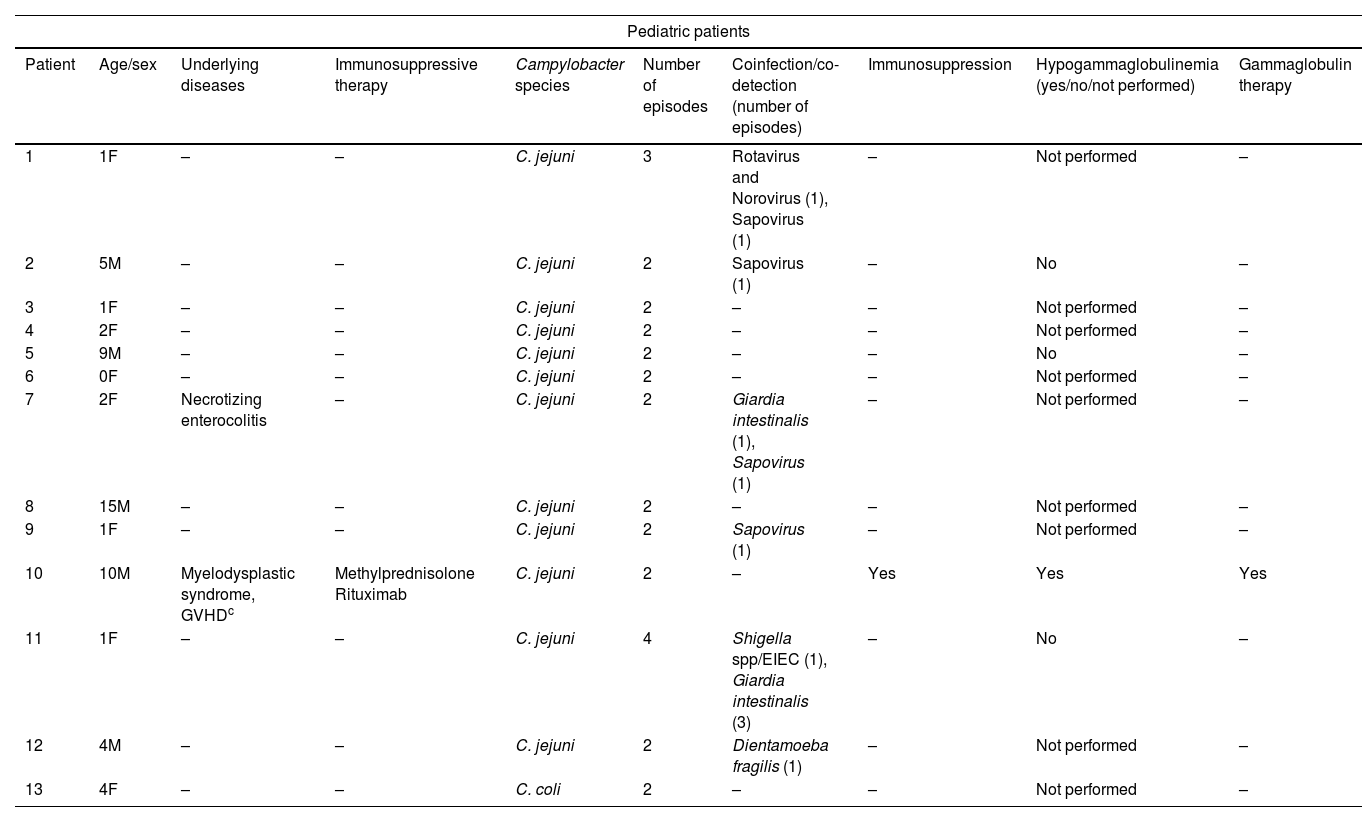

ResultsDuring the two-year study period, we identified 1.180 patients with positive PCR for Campylobacter spp. of those, 24 cases (2.03%) met the inclusion criteria of recurrent Campylobacter spp. gastroenteritis. Demographic and clinical features are collected in Table 1. Twenty-one patients presented recurrent enteritis by C. jejuni and three patients by C. coli. There were 13 male and 11 female patients with ages ranged from 6 months to 88 years old (mean: 26.9; median: 12.5).

Characteristics of pediatric and adult patients with recurrent Campylobacterjejuni/Campylobacter coli gastroenteritis.

| Pediatric patients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Age/sex | Underlying diseases | Immunosuppressive therapy | Campylobacter species | Number of episodes | Coinfection/co-detection (number of episodes) | Immunosuppression | Hypogammaglobulinemia (yes/no/not performed) | Gammaglobulin therapy |

| 1 | 1F | – | – | C. jejuni | 3 | Rotavirus and Norovirus (1), Sapovirus (1) | – | Not performed | – |

| 2 | 5M | – | – | C. jejuni | 2 | Sapovirus (1) | – | No | – |

| 3 | 1F | – | – | C. jejuni | 2 | – | – | Not performed | – |

| 4 | 2F | – | – | C. jejuni | 2 | – | – | Not performed | – |

| 5 | 9M | – | – | C. jejuni | 2 | – | – | No | – |

| 6 | 0F | – | – | C. jejuni | 2 | – | – | Not performed | – |

| 7 | 2F | Necrotizing enterocolitis | – | C. jejuni | 2 | Giardia intestinalis (1), Sapovirus (1) | – | Not performed | – |

| 8 | 15M | – | – | C. jejuni | 2 | – | – | Not performed | – |

| 9 | 1F | – | – | C. jejuni | 2 | Sapovirus (1) | – | Not performed | – |

| 10 | 10M | Myelodysplastic syndrome, GVHDc | Methylprednisolone Rituximab | C. jejuni | 2 | – | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | 1F | – | – | C. jejuni | 4 | Shigella spp/EIEC (1), Giardia intestinalis (3) | – | No | – |

| 12 | 4M | – | – | C. jejuni | 2 | Dientamoeba fragilis (1) | – | Not performed | – |

| 13 | 4F | – | – | C. coli | 2 | – | – | Not performed | – |

| Adult patients | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Age/sex | Underlying diseases | Immunosuppressive therapy | Campylobacter species | Number of episodes | Coinfection/co-detection (number of episodes) | Immunosuppression | Hypogamma-globulinemia (yes/no/not performed) | Gammaglobulin therapy | Chronic treatment azithromycin |

| 14 | 53M | LLC-Ba | Ibrutinib | C. jejuni | 2 | – | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| 15 | 47M | Chron disease | Infliximab | C. jejuni | 3 | C. difficile (1) | Yes | Not performed | – | – |

| 16 | 51F | Multiple myeloma | Bortezomib Daratumumab Dexamethasone | C. jejuni | 2 | – | Yes | Yes | – | – |

| 17 | 65M | CVIDb, gastric adenocarcinoma | – | C. jejuni | 5 | Giardia intestinalis (1) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | 88F | Colon carcinoma | – | C. coli | 2 | – | No | Not performed | – | |

| 19 | 49M | X-linked Agammaglobulinemia | – | C. jejuni | 8 | Giardia intestinalis (6) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 20 | 53F | Promyelocytic leukemia | Chemotherapy | C. jejuni | 2 | – | Yes | No | – | – |

| 21 | 39M | CVID, Diffuse large B-cell non-Hodkin lymphoma | Rituximab Prednisone | C. jejuni | 2 | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | – |

| 22 | 34M | CVID | Prednisone | C. coli | 6 | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 23 | 57M | Good Syndrome, Chron-like disease | Adalimumab Prednisone | C. jejuni | 16 | Clostridium difficile (2) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 24 | 55M | IgG lambda multiple myeloma, Squamous cell carcinoma | Prednisone Thalidomide | C. jejuni | 2 | – | Yes | No | – | – |

From the 24 patients reviewed we recorded 70 episodes of Campylobacter spp. gastroenteritis, 69 of them with diarrhea; only in one episode from one patient (patient no. 4) the reason of consultation was the presence of macroscopic blood in stools after receiving laxative treatment. One patient (patient no. 23) also developed two episodes of bacteremia due to C. jejuni; the patient was treated with azithromycin intravenously and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid intravenously respectively, the episodes that did not involve bacteremia were treated with azithromycin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid by mouth. This patient finally died of causes related to a respiratory infection.

In the adult population, the underlying diseases were heterogeneous, including 6 patients with different hematologic malignancies, 5 patients with primary immunodeficiency (Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), X- linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), and Good syndrome), 3 patients with non-hematologic tumors and 3 patients with inflammatory intestinal disorders. Moreover, 9 patients were receiving immunosuppressive therapy for cancer, graft-versus-host disease or inflammatory bowel disease. There were 11 patients without known risk factors or underlying diseases, all of them were pediatric patients (ages ranged from 6 months to 15 years old). Coinfection or co-detection with other gastrointestinal pathogens was documented in 21 (26%) episodes from 10 patients, with Giardia intestinalis being the most frequent microorganism involved.

Eight out of the 13 pediatric patients received antibiotic treatment for any of the episodes. Seven were treated with azithromycin and one with amoxicillin. Nine out of the 11 adult patients received antibiotic treatment for any of the episodes. The treatment received in adult patients were more diverse and complex and varied throughout the episodes. The most frequently antibiotic treatment used was azithromycin (6 patients) followed by amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (4 patients) and gentamicin (1 patient). In some episodes these treatments were combined with metronidazole or quinolone.

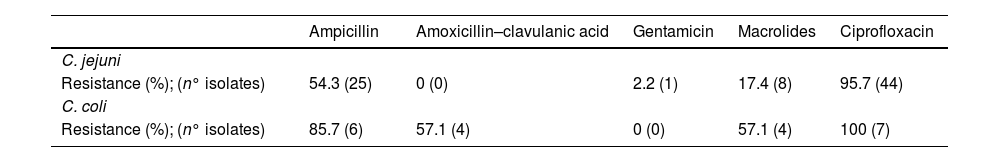

Of the 70 episodes detected by PCR there were 53 (75.7%) which were also isolated on culture; 52 of them with antibiogram available. The global pattern of resistance to the different antibiotics tested for C. jejuni and C. coli isolates is described in Table 2. Fourty-four (95.7%) isolates of C. jejuni were resistant to ciprofloxacin and 8 isolates (17.4%) to azithromycin. Seven out of 10 C. coli isolates had antibiogram available, all were resistant to ciprofloxacin and 4 to azithromycin. The patient no. 22, who had a CVID, had 6 episodes of recurrent campylobacteriosis caused by C. coli. When sensitivity was tested, all isolates were resistant to all antibiotics tested except to gentamicin, in these cases of multi-drug resistance, sensitivity to doxycycline and tetracycline was also tested, which also showed resistance. This patient underwent successive control cultures and in the cases that were positive and had symptoms, a course of gentamicin 5mg/kg/day for 7 days was administered. After the last episode, the control cultures were negative, and no further treatment was administered.

Global rates of resistance to the different antibiotics tested for Campylobacter spp.

| Ampicillin | Amoxicillin–clavulanic acid | Gentamicin | Macrolides | Ciprofloxacin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. jejuni | |||||

| Resistance (%); (n° isolates) | 54.3 (25) | 0 (0) | 2.2 (1) | 17.4 (8) | 95.7 (44) |

| C. coli | |||||

| Resistance (%); (n° isolates) | 85.7 (6) | 57.1 (4) | 0 (0) | 57.1 (4) | 100 (7) |

Campylobacter spp. is a leading cause of food-borne bacterial enteritis worldwide.9 The infection commonly presents as an acute invasive gastroenteritis characterized by diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea and fever.13 When symptomatic or asymptomatic recurrent infection occurs with the absence of repeated exposures to the microorganism, suggests that the original pathogen could not been completely eliminated from the host due to an insufficient immunologic response, a microbe containment of the reach of host immunity or antibiotics, or the development of antibiotic resistance.9

Here, we report 24 patients with a wide range of ages (6 months to 88 years old) with recurrent C. jejuni or C. coli infections. In our study, the vast majority of the episodes showed gastrointestinal symptoms and one patient suffered from campylobacteriosis with two episodes of bacteremia in the setting of Chron-like disease and Good syndrome. Complications such as bacteremia are uncommon, even though intestinal carriage is a risk factor for bacteremia in immunocompromised patients,1 Gharamti et al. reported the hypogammaglobulinemia as the main reason of recurrent episodes of Campylobacter spp. bacteremia.14

Regarding recrudescence of enteritis due to Campylobacter spp. there is also an increased risk in the population groups with underlying diseases. The literature reports some patients with primary immunodeficiency and recurrent Campylobacter spp. episodes, the published cases had primary hypogammaglobulinemia, most commonly in the setting of CVID, XLA, and Good syndrome.1,2,7,8 As well as other diseases related with impaired immune response such as AIDS, hematologic malignancies, non-hematologic tumors, chronic intestinal diseases, diabetes and liver disease. One study also linked an increased risk of recrudescence with the use of antibiotics and antacids.8 Our data showed that 13 out of 24 patients had different underlying diseases, 5 of them with primary immunodeficiency. Two of the patients in our study suffered from bowel inflammatory disease, such as Chron disease or ulcerative enterocolitis; gastrointestinal infections are commonly seen in these patients, more frequently due to C. jejuni, which could be implicated in the pathogenesis of the disease.15

In the setting of patients with immunosuppressive therapy, there is no evidence about an increased risk of recurrent Campylobacter spp. enteritis. Rituximab alone may not be sufficiently immunosuppressive for recurrent campylobacteriosis to occur and additional factors, including hematological malignancy and its treatment, appear to be necessary.1 In our cohort, one patient had CVID and diffuse large cell non-Hodkin lymphoma and received rituximab; he was admitted to our hospital with diarrhea, and both C. jejuni and norovirus were identified in stool samples. The repeated infections of these microorganisms were more likely associated with the hypogammaglobulinemia than with the rituximab treatment; since, despite the withdrawal of monoclonal antibody therapy, C. jejuni isolates persisted even after the antibiotic treatment with azithromycin and fluorquinolones.

On the other hand, 11 patients had not known risk factors or underlying diseases and all this group correspond to pediatric patients (<16 years old). This could be due to the lack of acquired immunity in this population group. Previous studies have found that the percentage of people with specific IgG antibodies to C. jejuni increases with age. This is supported by the fact that the highest incidence of infection occurs in the 0–4 years old age group but a reduction of the incidence is observed in adults >30 years.16 In developing countries, with higher risk of exposure; the development of acquired immunity against Campylobacter spp. is most likely and the percentage of asymptomatic carriers is higher. However, in industrialized countries, the exposure to Campylobacter spp. is considered much lower, which translates into less effective immunity, lower incidence rates of campylobacteriosis in children and a lower percentage of carriers.8

In the cohort of patients reviewed we observed frequently coinfections or co-detections with other enteropathogens. Coinfections with two or more enteric agents are common and may be explained through a shared mechanism of transmission.17,18 The recent application of molecular techniques for the routine diagnosis of gastroenteritis have revealed high rates of coinfection or co-detection with enteric pathogens but further studies are required to determine which pathogens are more or less likely to occur together and which combination are positively or negatively associated with the pathogenesis and symptoms.18 In our study, Giardia intestinalis was the most common pathogen detected together with Campylobacter spp. Malgorzataet al. reports patients with primary hypogammaglobulinemia, such as XLA, presenting prolonged diarrhea caused by G. intestinalis, Campylobacter spp., Salmonella and others.19 Some studies also observed G. intestinalis in patients with immunodeficiency, such as XLA or SCID, as a possible cause of intestinal malabsorption20 or chronic diarrhea in patients with CVID.

Although culturing is the current gold standard for detection of bacterial enteropathogens, PCR is more reliable and faster.21 Liu et al. in an analysis of the infectious etiology of diarrhea in the Global Enteric Multicenter Study showed that PCR could detect bacterial, parasitic and viral pathogens across multiple laboratories with high sensitivity and good reproducibility and that many enteric pathogens were underestimated with the traditional diagnostic methods.17 In our study 17 out of 70 episodes could not been isolated by culturing. This could be due to the detection by PCR of nonviable or low concentrations of bacteria in patients that were being treated, with recent resolved disease or with recent infection.

Gastrointestinal manifestations of campylobacteriosis in healthy individuals often resolve completely without the use of antibiotics. The use of antibiotics for the treatment of these infections is reserved for patients with moderate or severe disease, signs of systemic infection or underlying immunodeficiency. The antimicrobial therapy recommended includes a macrolide antibiotic (i.e. azithromycin for 3 days), fluoroquinolone use is limited in the setting of Campylobacter spp. resistance but is effective against sensitive strains.9 Occasionally, severe systemic infection requires the use of an aminoglycoside (i.e. gentamicin).22 Antimicrobial drug resistance in Campylobacter spp. infections has increased in many developed and developing countries, in particular to fluoroquinolones, macrolides, aminoglycosides and tetracyclines. Campylobacter spp. isolates are usually resistant to ciprofloxacin (rates in Spain are around 85%) while rates of resistance to macrolides are low worldwide (rates in Spain are around 3.3% in C. jejuni and 27% in C. coli).23,24 In our study, we obtained similar results when testing ciprofloxacin resistance, but when testing macrolides, we obtained higher resistance rates that may be due to an increased number of antibiotic treatment cycles given to these patients. Resistances to gentamicin is no as usual24; that is the reason why in cases of multidrug-resistant Campylobacter spp. infection, as one of the cases described herein, a treatment with gentamicin is the optimal option.23 In addition, it has been found that in these cases oral fosfomycin-trometamol can also be administered,25 provided that the MIC is low, since some studies have described cases of high MICs in adults.26

The limitation of the retrospective nature of this study should be taken into consideration as well as the relatively small number of patients. Additionally, we did not carry out a molecular typing or whole genome sequencing of the Campylobacter spp. isolates to differentiate reinfections from persistent infections that remain latent. Furthermore, the inclusion criteria were patients with positive PCR for Campylobacter spp. regardless of its recovery on culture that could have led to an overestimation of cases or episodes.

In conclusion, clinicians should be aware of the association of recurrent campylobacteriosis and immunodeficiency in adult patients, especially humoral immunodeficiency. However, in the industrialized urban setting where this study was conducted, recurrent Campylobacter spp. gastroenteritis in children without risk factors or underlying diseases probably reflects the lack of acquired immunity. The higher rates of resistance to macrolides achieved in these Campylobacter spp. isolates comparing with the rates previously reported reveals the repeated antibiotic cycles given to these patients.

Authors’ contributionsStudy conception and design: CG, JG, GR.

Acquisition of data: CG, GR.

Analysis and interpretation of data: CG, GR.

Drafting of manuscript: Critical revision: all authors.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Not applicable.