New strategies need to be developed for the early recognition and rapid response for the management of sepsis. To achieve this purpose, the Multidisciplinary Sepsis Team (MST) developed the Computerized Sepsis Protocol Management (PIMIS). The aim of this study was to evaluate the convenience of using PIMIS, as well as the activity of the MST.

MethodsAn analysis was performed on the data collected from solicited MST consultations (direct activation of PIMIS by attending physician or telephone request) and unsolicited ones (by referral from the microbiology laboratory or an automatic referral via the hospital vital signs recording software [SIDCV]), as well as the hospital department, source of infection, treatment recommendation, and acceptance of this.

ResultsOf the 1581 first consultations, 65.1% were solicited consultations (84.1% activation of PIMIS and 15.9% by telephone). The majority of unsolicited consultations were generated by the microbiology laboratory (95.2%), and 4.8% from the SIDCV. Referral from solicited consultations were generated sooner (5.63days vs 8.47days; p<0.001) and came from clinical specialties rather than from the surgical ward (73.0% vs 39.1%; p<0.001). A recommendation was made for antimicrobial prescription change in 32% of first consultations. The treating physician accepted 78.1% of recommendations.

ConclusionsThe high rate of solicited consultations and acceptance of recommended prescription changes suggest that a MST is seen as a helpful resource, and that PIMIS software is perceived to be useful and convenient to use, as it is the main source of referral.

Es preciso desarrollar nuevas estrategias que permitan una identificación precoz y una inmediata instauración de medidas efectivas en el abordaje de la sepsis. La unidad multidisciplinar de sepsis (UMS) desarrolló una herramienta: el Protocolo Informático de Manejo Integral de la Sepsis (PIMIS). El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar la intervención de la UMS y la utilidad del PIMIS.

MétodosSe analizaron las intervenciones según fueran realizadas por consulta directamente solicitada (activación de PIMIS o consulta telefónica) o no solicitada (aislamientos microbiológicos y el Sistema Informático de Detección de Constantes Vitales [SIDCV]), los servicios, el tipo de infección, la recomendación de cambio de antibiótico y el grado de aceptación.

ResultadosDe las 1.581 consultas, el 65,1% se solicitaron directamente: un 84,1% por activación del PIMIS por el médico responsable y un 15,9% por contacto telefónico directo. Entre las consultas no solicitadas, el 95,2% procedían de microbiología y el 4,8% del SIDCV. Las consultas directamente solicitadas se realizaron más precozmente que las no solicitadas (5,63días vs. 8,47días; p<0,001) y la frecuencia fue mayor en los servicios médicos frente a los quirúrgicos (73,0% vs. 39,1%; p<0,001). Se recomendó un cambio de antibiótico en el 32% de las primeras consultas y se aceptó en el 78,1% de los casos.

ConclusionesLa elevada proporción de consultas directamente solicitadas y aceptación de las recomendaciones demuestra que la intervención de la UMS es valorada y respetada. El PIMIS es el principal mecanismo de consulta, lo que lo convierte en una herramienta útil y conveniente para la identificación precoz y el abordaje de la sepsis.

Sepsis is still one of the leading causes of death among hospitalized patients. In Spain, the latest studies show that there has been an increase in its incidence.1 Thus, it is essential to develop early detection mechanisms and tools in order to prevent the development of complications.

During the last few years, different strategies have been created in order to improve the management of sepsis, some of them originated in the critical care medicine department or in the internal medicine unit.2,3 Also, the essential role played by the nursing team in its detection and follow-up has been stressed out.4,5

In an attempt to improve the comprehensive management of patients with sepsis, back in the year 2006 our center created the very first multidisciplinary unit in sepsis care (MUSC) in Spain. The team included one (1) doctor with specific formation in infectious diseases plus one (1) nurse with exclusive dedication, and one (1) multidisciplinary team with partial dedication including specialists on the following medical fields: intensive medicine; ER; pneumology; internal medicine; pharmacy; microbiology; and general surgery.

The MUSC has a triple goal. In the first place, it is focused on promoting the early detection of severe sepsis. Secondly, on implementing measures for the management and treatment of sepsis based on the guidelines proposed by the Surviving Sepsis Campaing.6 Thirdly, the MUSC aims at optimizing antibiotic treatments.

The involvement of a specialist on infectious diseases has been confirmed to improve the prognosis of these patients.7,8 At some centers, other multidisciplinary teams have been implementing programs to optimize the antibiotic treatment resulting in an improvement of both the prescription process and the use of antibiotics.9,10

In order to guarantee an early intervention, the MUSC created one computerized tool: The Computerized Protocol for the Comprehensive Management of Sepsis (PIMIS, in Spanish). Its goals are: to allow the early identification of sepsis and the immediate implementation of a set of effective measures in order to avoid the development of complications and improve the prognosis of patients.

This study describes the development and implementation of the PIMIS.

MethodsOne observational, descriptive and retrospective study was conducted between January 1st 2011 and June 30th, 2012 where the following variables were gathered: the different mechanisms of inclusion of a patient in the PIMIS; the unit the patient had been referred from; the days elapsed between the patient's admission and the medical consultation (DMC); the source of infection; the etiology (nosocomial); the type of recommendation in the change of antibiotic treatment and the degree of acceptance of the adults patients included in the PIMIS and hospitalized in the Hospital Son Llàtzer. This hospital provides healthcare to 225,000 people and has 400 beds.

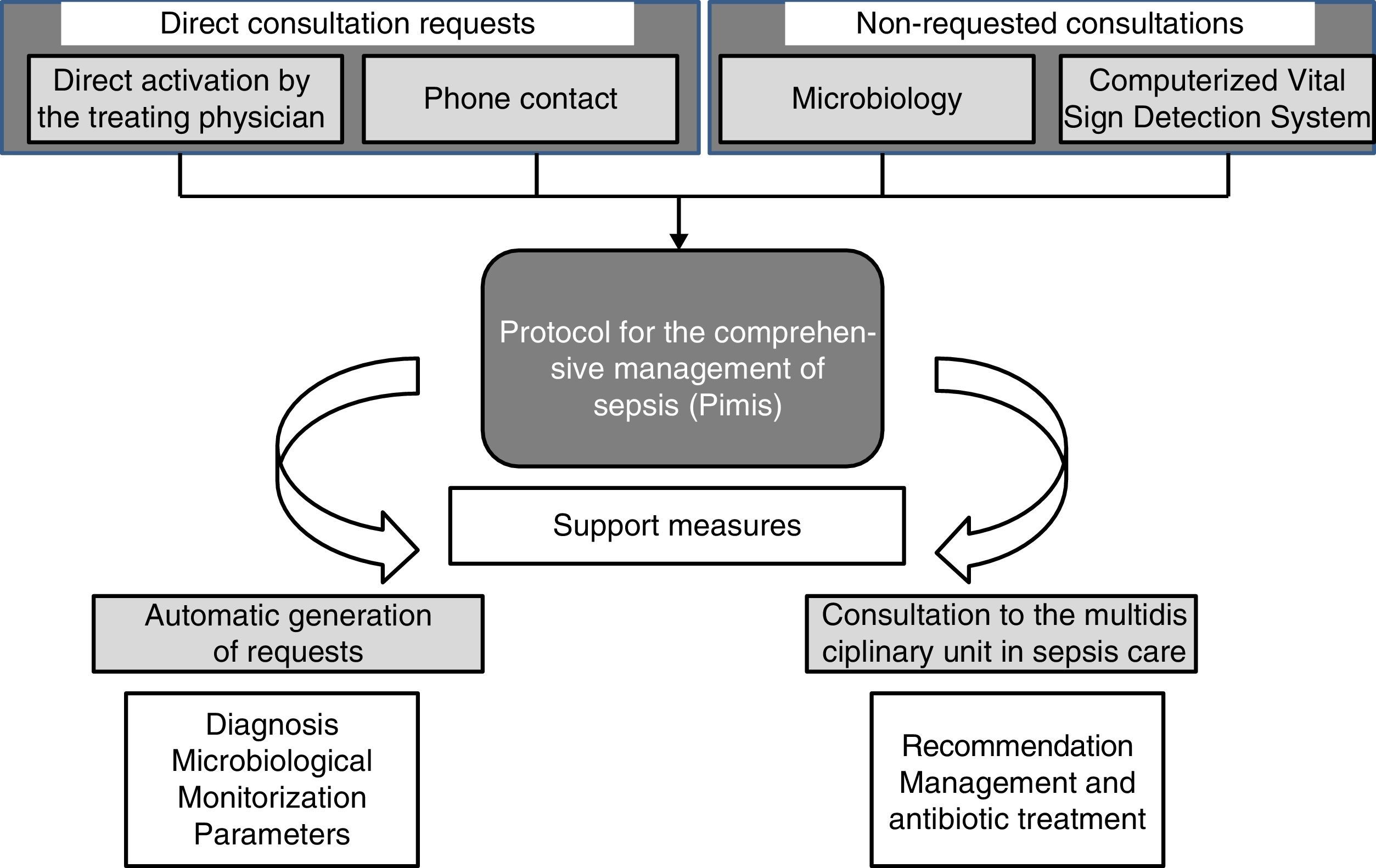

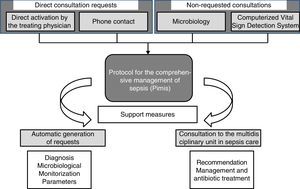

Four (4) different mechanisms can make a patient enter the PIMIS: (1) through direct computerized activation by his treating physician; (2) through direct telephone consultation with the MUSC; (3) after confirmation of significant microbiological isolation; and (4) once the alert from the Computerized Vital Sign Detection System (CVSDS) has gone off. We talk about direct consultation requests (DCR) whenever a patient enters the PIMIS through direct request by his treating physician or through the phone, while non-requested consultations (NRC) are those when the patient enters the PIMIS after all the microbiological information has been collected or the alert from the CVSDS has gone off (Fig. 1).

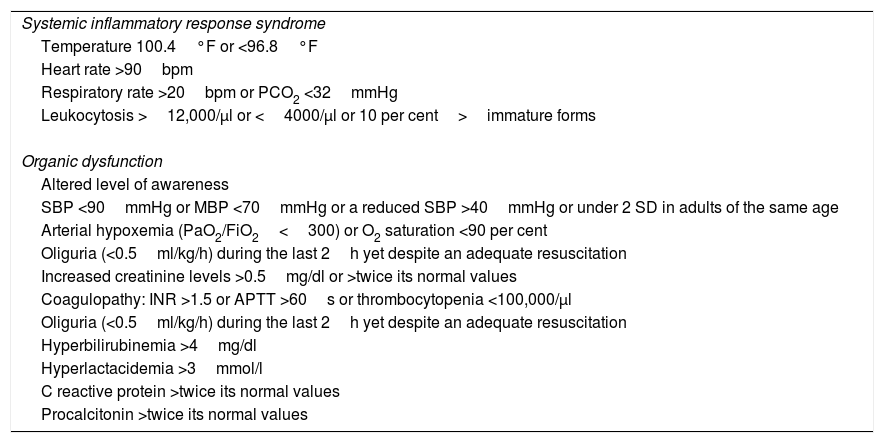

When a patient is suspicious of suffering from severe sepsis, after selecting the PIMIS tool, one check-list opens with the criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS); organic dysfunction; and inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein; normal <5mg/l and procalcitonin; normal <0–05ng/ml) (Table 1). When, at least, two (2) criteria for SIRS and one (1) criterion for organic dysfunction are met, or the markers are high, the patient's condition is identified as severe sepsis and after check-list validation, the automatic activation of the protocol is generated. Once the patient has been included in the PIMIS, an automatic alert is sent to the MUSC through the generation of one list that identifies both the patient and his inclusion criteria. From that very moment, the patient is assessed by someone at the MUSC who will make all the necessary recommendations on the management and specific treatment of the patient. The PIMIS can be activated from all hospital units.

Activation criteria for the protocol for the comprehensive management of sepsis.

| Systemic inflammatory response syndrome |

| Temperature 100.4°F or <96.8°F |

| Heart rate >90bpm |

| Respiratory rate >20bpm or PCO2 <32mmHg |

| Leukocytosis >12,000/μl or <4000/μl or 10 per cent>immature forms |

| Organic dysfunction |

| Altered level of awareness |

| SBP <90mmHg or MBP <70mmHg or a reduced SBP >40mmHg or under 2 SD in adults of the same age |

| Arterial hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2<300) or O2 saturation <90 per cent |

| Oliguria (<0.5ml/kg/h) during the last 2h yet despite an adequate resuscitation |

| Increased creatinine levels >0.5mg/dl or >twice its normal values |

| Coagulopathy: INR >1.5 or APTT >60s or thrombocytopenia <100,000/μl |

| Oliguria (<0.5ml/kg/h) during the last 2h yet despite an adequate resuscitation |

| Hyperbilirubinemia >4mg/dl |

| Hyperlactacidemia >3mmol/l |

| C reactive protein >twice its normal values |

| Procalcitonin >twice its normal values |

SD: standard deviation; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; INR: international normalized ratio; MBP: mean blood pressure; PaO2: partial pressure of oxygen; SBP: systolic blood pressure; PCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide; SIRS: systemic inflammatory response syndrome; APTT: activated partial thromboplastin time.

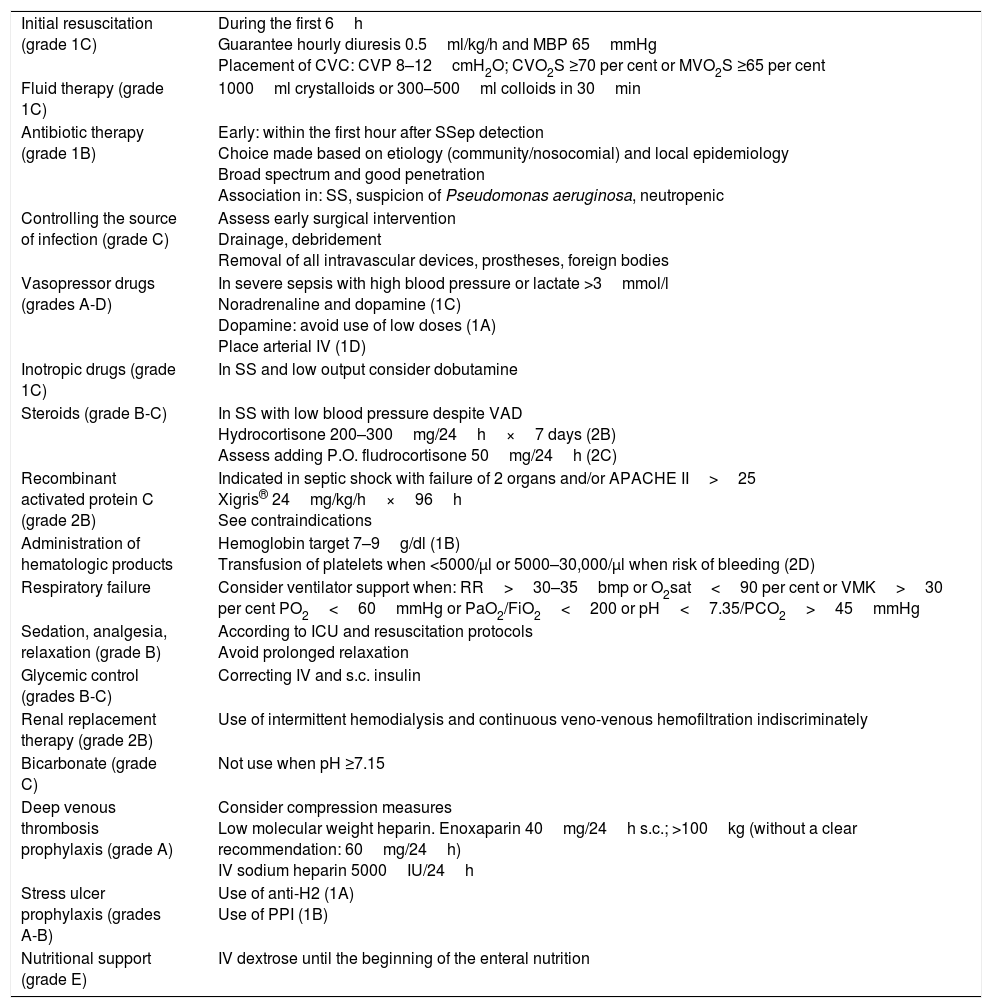

Parallel to the creation of a list of the patients included, recommendations are made on what therapeutic management should be followed: initial resuscitation; hemodynamic support; and individualized associated therapies based on the recommendations from the Surviving Sepsis Campaing11 (Table 2), plus a series of requirements: blood culture extractions; chest x-rays; lactate extractions for monitoring purposes and organic dysfunction parameters; CRP and PCT both 6 and 24h after the inclusion of the patient (always) and the microbiological sample collection (if applicable). The activation of a patient in the PIMIS due to microbiological isolation usually happens after holding the daily meeting with the microbiology unit, and once the results from the most significant samples have been disclosed. With these results, it is time for the clinical assessment of the patient and should he meet the criteria for sepsis, he enters and is activated through the PIMIS.

Recommendations for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock.

| Initial resuscitation (grade 1C) | During the first 6h Guarantee hourly diuresis 0.5ml/kg/h and MBP 65mmHg Placement of CVC: CVP 8–12cmH2O; CVO2S ≥70 per cent or MVO2S ≥65 per cent |

| Fluid therapy (grade 1C) | 1000ml crystalloids or 300–500ml colloids in 30min |

| Antibiotic therapy (grade 1B) | Early: within the first hour after SSep detection Choice made based on etiology (community/nosocomial) and local epidemiology Broad spectrum and good penetration Association in: SS, suspicion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, neutropenic |

| Controlling the source of infection (grade C) | Assess early surgical intervention Drainage, debridement Removal of all intravascular devices, prostheses, foreign bodies |

| Vasopressor drugs (grades A-D) | In severe sepsis with high blood pressure or lactate >3mmol/l Noradrenaline and dopamine (1C) Dopamine: avoid use of low doses (1A) Place arterial IV (1D) |

| Inotropic drugs (grade 1C) | In SS and low output consider dobutamine |

| Steroids (grade B-C) | In SS with low blood pressure despite VAD Hydrocortisone 200–300mg/24h×7 days (2B) Assess adding P.O. fludrocortisone 50mg/24h (2C) |

| Recombinant activated protein C (grade 2B) | Indicated in septic shock with failure of 2 organs and/or APACHE II>25 Xigris® 24mg/kg/h×96h See contraindications |

| Administration of hematologic products | Hemoglobin target 7–9g/dl (1B) Transfusion of platelets when <5000/μl or 5000–30,000/μl when risk of bleeding (2D) |

| Respiratory failure | Consider ventilator support when: RR>30–35bmp or O2sat<90 per cent or VMK>30 per cent PO2<60mmHg or PaO2/FiO2<200 or pH<7.35/PCO2>45mmHg |

| Sedation, analgesia, relaxation (grade B) | According to ICU and resuscitation protocols Avoid prolonged relaxation |

| Glycemic control (grades B-C) | Correcting IV and s.c. insulin |

| Renal replacement therapy (grade 2B) | Use of intermittent hemodialysis and continuous veno-venous hemofiltration indiscriminately |

| Bicarbonate (grade C) | Not use when pH ≥7.15 |

| Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis (grade A) | Consider compression measures Low molecular weight heparin. Enoxaparin 40mg/24h s.c.; >100kg (without a clear recommendation: 60mg/24h) IV sodium heparin 5000IU/24h |

| Stress ulcer prophylaxis (grades A-B) | Use of anti-H2 (1A) Use of PPI (1B) |

| Nutritional support (grade E) | IV dextrose until the beginning of the enteral nutrition |

CVC: central venous catheter; VAD: vasoactive drugs; RR: respiratory rate; PPI: proton pump inhibitors; IV: intravenous; MBP: mean blood pressure; PCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2: partial pressure of oxygen; CVP: central venous pressure; s.c.: subcutaneous; O2sat: oxygen saturation; CVO2S: central venous oxygen saturation; MVO2S: mixed venous oxygen saturation; SSep: severe sepsis; SS: septic shock; ICU: intensive care unit; VMK: ventimask; P.O.: orally.

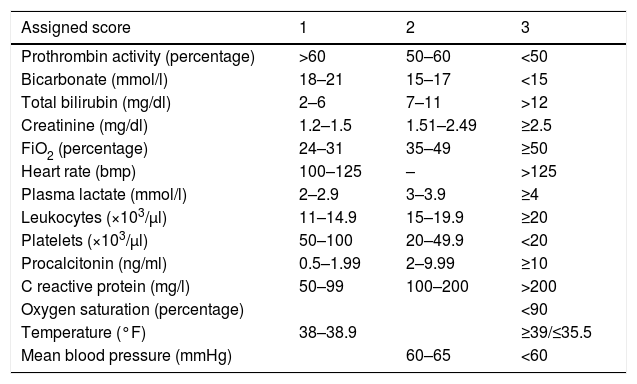

With the hemodynamic parameters introduced in the nursing computing system together with some predefined laboratory values, one score is generated that categorizes the patient as suspicious of sepsis with scores >6 points (Table 3). The score should always be obtained during the last 24h. The MUSC receives an alert with the list of patients whose score is over 6 points every 24h. This system has been part of a pilot study to assess its internal validity during the last few months of the study.

Score criteria in the Computerized Vital Sign Detection System (CVSDS).

| Assigned score | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prothrombin activity (percentage) | >60 | 50–60 | <50 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/l) | 18–21 | 15–17 | <15 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 2–6 | 7–11 | >12 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.2–1.5 | 1.51–2.49 | ≥2.5 |

| FiO2 (percentage) | 24–31 | 35–49 | ≥50 |

| Heart rate (bmp) | 100–125 | – | >125 |

| Plasma lactate (mmol/l) | 2–2.9 | 3–3.9 | ≥4 |

| Leukocytes (×103/μl) | 11–14.9 | 15–19.9 | ≥20 |

| Platelets (×103/μl) | 50–100 | 20–49.9 | <20 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/ml) | 0.5–1.99 | 2–9.99 | ≥10 |

| C reactive protein (mg/l) | 50–99 | 100–200 | >200 |

| Oxygen saturation (percentage) | <90 | ||

| Temperature (°F) | 38–38.9 | ≥39/≤35.5 | |

| Mean blood pressure (mmHg) | 60–65 | <60 |

FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen.

The members of the MUSC are distributed and proceed with the daily assessment of the patients included in the PIMIS and/or selected by the CVSDS in order to ensure that they meet the clinical criteria for sepsis; if so, follow-up is continued until the end of the process. During the first consultation, certain therapeutic recommendations are made and then communicated directly to the treating physician and shown in an inter-consultation report. The recommendations to change the antibiotic treatment can be of four (4) different types: (a) de-escalation–when the number of antibiotics or the antibiotic spectrum is reduced based on the pattern of resistances; (b) change due to poor progression–when there are clinical and/or analytical criteria for SIRS or organic dysfunction beyond the first 72h; (c) dose adjustment or inadequate treatment–when the antibiotic does not have in vitro activity or cannot adequately treat the source of infection, or its administration can lead to adverse events that exceed all expected benefits; and (d) sequential therapy–when goin from IV administration to oral administration. The optimization of the antibiotic treatment is supervised by a pharmaceutical expert from the MUSC.

The recommendation is accepted when the change of antibiotic treatment matches the recommendation made by the MUSC.

The categorical variables are expressed as relative and absolute frequences. The continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviations (SD) and compared using the t-Student t test, or the ANOVA test for the study of variables with normal distribution, and the Mann–Whitney t test for the study of variables with non-normal distribution. The statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS software version 17.0 (Chicago, IL, USA), and the EPIDAT software version 3.1.

ResultsDuring the study period, 1581 new consultations at the MUSC were reported on 1340 patients – averaging some 89 new consultations/month; 78.5 per cent were community episodes.

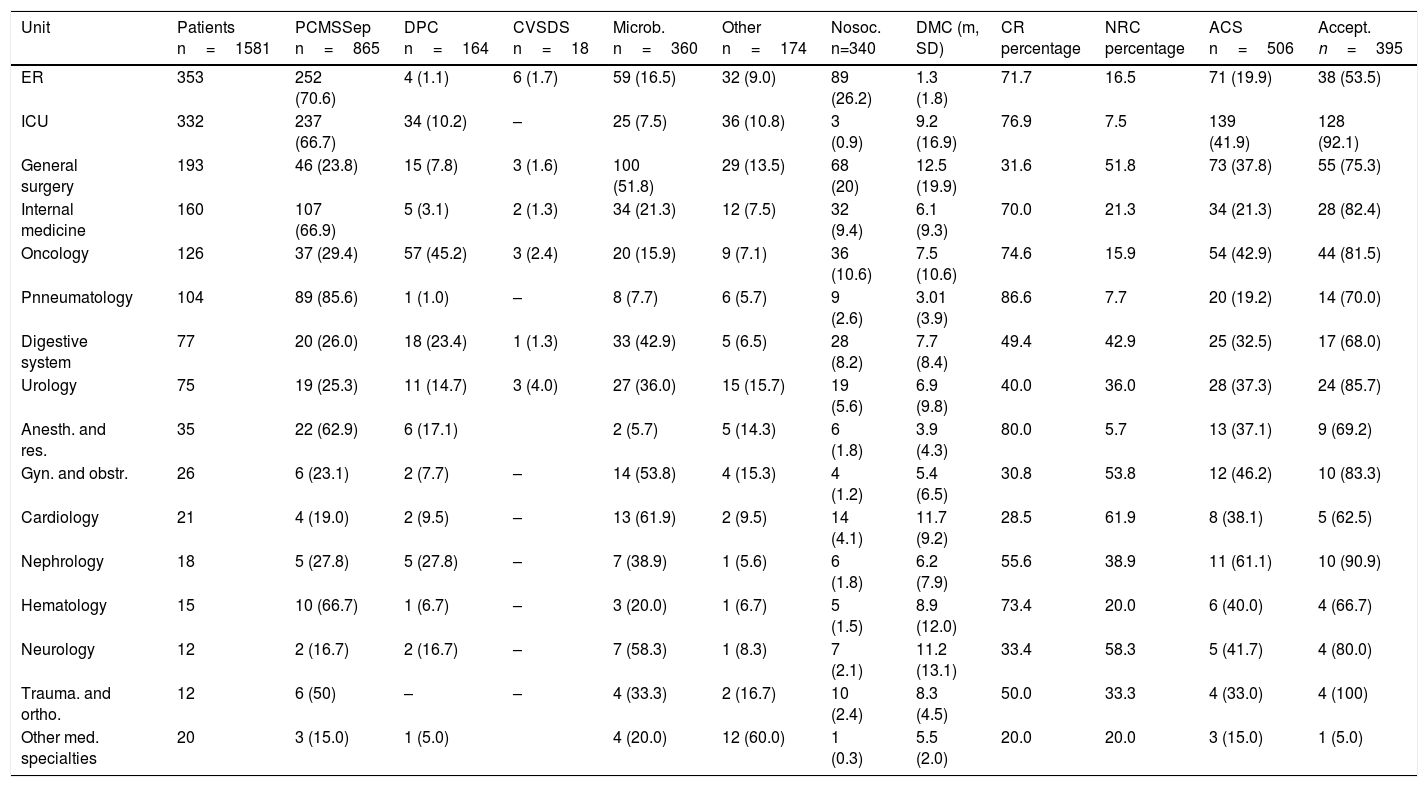

Both the referral unit of the patient and the type of consultation made are shown in Table 4. The ER (22.6 per cent) and the ICU (21 per cent) were the units that handled the largest number of consultations.

Mechanism of consultation and treatment modification per unit.

| Unit | Patients n=1581 | PCMSSep n=865 | DPC n=164 | CVSDS n=18 | Microb. n=360 | Other n=174 | Nosoc. n=340 | DMC (m, SD) | CR percentage | NRC percentage | ACS n=506 | Accept. n=395 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | 353 | 252 (70.6) | 4 (1.1) | 6 (1.7) | 59 (16.5) | 32 (9.0) | 89 (26.2) | 1.3 (1.8) | 71.7 | 16.5 | 71 (19.9) | 38 (53.5) |

| ICU | 332 | 237 (66.7) | 34 (10.2) | – | 25 (7.5) | 36 (10.8) | 3 (0.9) | 9.2 (16.9) | 76.9 | 7.5 | 139 (41.9) | 128 (92.1) |

| General surgery | 193 | 46 (23.8) | 15 (7.8) | 3 (1.6) | 100 (51.8) | 29 (13.5) | 68 (20) | 12.5 (19.9) | 31.6 | 51.8 | 73 (37.8) | 55 (75.3) |

| Internal medicine | 160 | 107 (66.9) | 5 (3.1) | 2 (1.3) | 34 (21.3) | 12 (7.5) | 32 (9.4) | 6.1 (9.3) | 70.0 | 21.3 | 34 (21.3) | 28 (82.4) |

| Oncology | 126 | 37 (29.4) | 57 (45.2) | 3 (2.4) | 20 (15.9) | 9 (7.1) | 36 (10.6) | 7.5 (10.6) | 74.6 | 15.9 | 54 (42.9) | 44 (81.5) |

| Pnneumatology | 104 | 89 (85.6) | 1 (1.0) | – | 8 (7.7) | 6 (5.7) | 9 (2.6) | 3.01 (3.9) | 86.6 | 7.7 | 20 (19.2) | 14 (70.0) |

| Digestive system | 77 | 20 (26.0) | 18 (23.4) | 1 (1.3) | 33 (42.9) | 5 (6.5) | 28 (8.2) | 7.7 (8.4) | 49.4 | 42.9 | 25 (32.5) | 17 (68.0) |

| Urology | 75 | 19 (25.3) | 11 (14.7) | 3 (4.0) | 27 (36.0) | 15 (15.7) | 19 (5.6) | 6.9 (9.8) | 40.0 | 36.0 | 28 (37.3) | 24 (85.7) |

| Anesth. and res. | 35 | 22 (62.9) | 6 (17.1) | 2 (5.7) | 5 (14.3) | 6 (1.8) | 3.9 (4.3) | 80.0 | 5.7 | 13 (37.1) | 9 (69.2) | |

| Gyn. and obstr. | 26 | 6 (23.1) | 2 (7.7) | – | 14 (53.8) | 4 (15.3) | 4 (1.2) | 5.4 (6.5) | 30.8 | 53.8 | 12 (46.2) | 10 (83.3) |

| Cardiology | 21 | 4 (19.0) | 2 (9.5) | – | 13 (61.9) | 2 (9.5) | 14 (4.1) | 11.7 (9.2) | 28.5 | 61.9 | 8 (38.1) | 5 (62.5) |

| Nephrology | 18 | 5 (27.8) | 5 (27.8) | – | 7 (38.9) | 1 (5.6) | 6 (1.8) | 6.2 (7.9) | 55.6 | 38.9 | 11 (61.1) | 10 (90.9) |

| Hematology | 15 | 10 (66.7) | 1 (6.7) | – | 3 (20.0) | 1 (6.7) | 5 (1.5) | 8.9 (12.0) | 73.4 | 20.0 | 6 (40.0) | 4 (66.7) |

| Neurology | 12 | 2 (16.7) | 2 (16.7) | – | 7 (58.3) | 1 (8.3) | 7 (2.1) | 11.2 (13.1) | 33.4 | 58.3 | 5 (41.7) | 4 (80.0) |

| Trauma. and ortho. | 12 | 6 (50) | – | – | 4 (33.3) | 2 (16.7) | 10 (2.4) | 8.3 (4.5) | 50.0 | 33.3 | 4 (33.0) | 4 (100) |

| Other med. specialties | 20 | 3 (15.0) | 1 (5.0) | 4 (20.0) | 12 (60.0) | 1 (0.3) | 5.5 (2.0) | 20.0 | 20.0 | 3 (15.0) | 1 (5.0) |

Accept.: antibiotic change accepted; Anesth. and res.: anesthesiology and resuscitation; ACS: antibiotic change suggested; CR: consultation requested; DPC: direct phone contact; DMC: days until medical consultation; Gyn. and obstr.: gynecology and obstetrics; Microb.: Microbiological isolation; NRC: non-requested consultation; Nosoc.: nosocomial; PCMSSep: Protocol for the comprehensive management of severe sepsis; CVSDS: Computerized Vital Sign Detection System; Req.: consultation requested; Trauma. and ortho.: traumatology and orthopedics; ICU: intensive care unit; ER: emergency room.

The leading mechanism of consultation was direct activation of the PIMIS by the treating physician (54.7 per cent). Basically, the patients were being referred from medical units (91.1 per cent); the ER (29.1 per cent) followed by the ICU (27.4 per cent); the internal medicine unit (12.4 per cent); and the pneumology unit (10.3 per cent), respectively.

The second mechanism of inclusion in the PIMIS followed the microbiological information collected (22.8 per cent). Over half the patients assessed were included through this mechanism in several units: cardiology (61.9 per cent); neurology (58.3 per cent); gynecology and obstetrics (53.8 per cent); and general surgery units (51.8 per cent).

The direct phone contact was responsible for 10.4 per cent of all inclusions in the PIMIS coming these referrals from oncology units (34.7 per cent); the ICU (20.7 per cent); and digestive system units (10.9 per cent). The CVSDS identified only 18 patients with sepsis, which amounts to only 1.1 per cent of all consultations made.

Direct consultation requests (DCR) vs non-requested consultations (NRC)Most consultations were DCRs (65.1 per cent). Among them, 84.1 per cent were the result of activation of the PIMIS by the treating physician, and 15.9 per cent by activation through direct pone contact. The percentage was significantly higher in the medical units compared to the surgical units (73.0 per cent vs 39.1 per cent; p<0.001). Similarly, The DCRs happened much earlier (5.63days vs 8.47days; p<0.001); 95.2 per cent of all NRCs came from microbiology, and 4.8 per cent from the CVSDS. The time elapsed between the patient's admission and the MUSC medical consultation is shown in Table 4 (days until medical consultation [DMC]). The DCRs made through PIMIS direct activation happened earlier than the DCRs made through direct phone contact (4.93days vs 9.33days; p<0.001).

Source of infectionAt the first consultation, the most common infection was of respiratory origin (34.4 per cent), followed by abdominal origin (22.4 per cent); and then urinary origin (18.2 per cent). In 23.9 per cent of the cases the source of infection could not be identified.

Recommendation of antibiotic changeThe change of antibiotics was recommended in 506 (32 per cent) of the first consultations, and later accepted in 398 cases (78.1 per cent). The frequency of acceptance was widely variable among the different medical specialties. The percentage of acceptance was significantly higher in the DCRs (80.6 per cent vs 72.4 per cent; p=0.04).

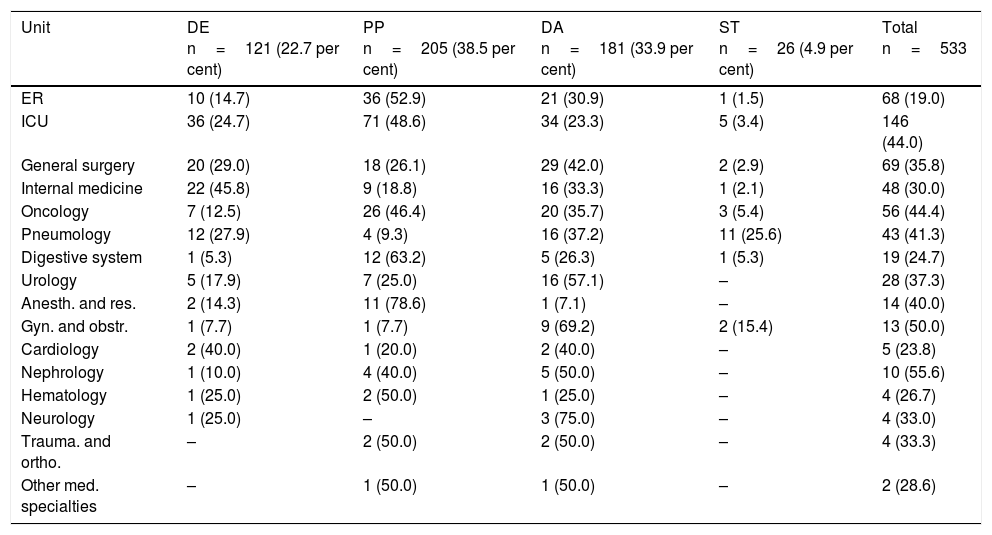

Types of recommendationThe main reason to recommend a change in the antibiotic regime was poor progression (38.5 per cent) followed by inadequate treatment (33.9 per cent) (Table 5). The units where these changed occurred due to poor progression of the patient were mainly the anesthesiology and resuscitation unit (78.6 per cent); the digestive system unit (63.2 per cent) followed by the ER (52.9 per cent) and the ICU (48.6 per cent). Dose adjustment was the most common intervention in the surgical unit (general surgery; gynecology and obstetrics; urology; traumatology), as well as in the cardiology and neurology units. De-escalation was the main intervention in the internal medicine unit (45.8 per cent), while the sequential therapy was the main intervention in the neumology unit (25.6 per cent).

Type of intervention conducted per unit.

| Unit | DE n=121 (22.7 per cent) | PP n=205 (38.5 per cent) | DA n=181 (33.9 per cent) | ST n=26 (4.9 per cent) | Total n=533 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | 10 (14.7) | 36 (52.9) | 21 (30.9) | 1 (1.5) | 68 (19.0) |

| ICU | 36 (24.7) | 71 (48.6) | 34 (23.3) | 5 (3.4) | 146 (44.0) |

| General surgery | 20 (29.0) | 18 (26.1) | 29 (42.0) | 2 (2.9) | 69 (35.8) |

| Internal medicine | 22 (45.8) | 9 (18.8) | 16 (33.3) | 1 (2.1) | 48 (30.0) |

| Oncology | 7 (12.5) | 26 (46.4) | 20 (35.7) | 3 (5.4) | 56 (44.4) |

| Pneumology | 12 (27.9) | 4 (9.3) | 16 (37.2) | 11 (25.6) | 43 (41.3) |

| Digestive system | 1 (5.3) | 12 (63.2) | 5 (26.3) | 1 (5.3) | 19 (24.7) |

| Urology | 5 (17.9) | 7 (25.0) | 16 (57.1) | – | 28 (37.3) |

| Anesth. and res. | 2 (14.3) | 11 (78.6) | 1 (7.1) | – | 14 (40.0) |

| Gyn. and obstr. | 1 (7.7) | 1 (7.7) | 9 (69.2) | 2 (15.4) | 13 (50.0) |

| Cardiology | 2 (40.0) | 1 (20.0) | 2 (40.0) | – | 5 (23.8) |

| Nephrology | 1 (10.0) | 4 (40.0) | 5 (50.0) | – | 10 (55.6) |

| Hematology | 1 (25.0) | 2 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | – | 4 (26.7) |

| Neurology | 1 (25.0) | – | 3 (75.0) | – | 4 (33.0) |

| Trauma. and ortho. | – | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | – | 4 (33.3) |

| Other med. specialties | – | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | – | 2 (28.6) |

DA: dose adjustment; Anesth. and res.: anesthesiology and resuscitation; DE: de-escalation; Gyn. and obstr.: gynecology and obstetrics; PP: poor progression; Trauma. and ortho.: traumatology and orthopedics; ST: sequential therapy; ICU: intensive care unit; ER: emergency room.

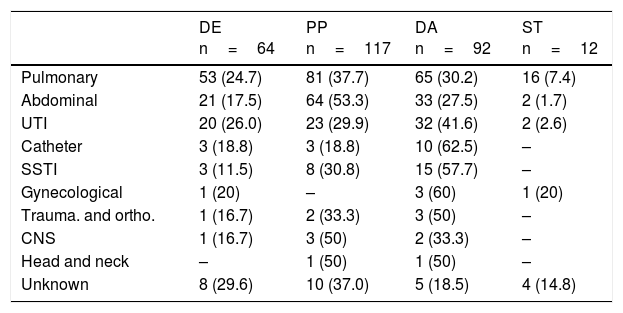

The antibiotic dose adjustment was the most common intervention in the management of infections like urinary tract infections (UTI); catheter-related infections; skin infections; and skin and soft tissue infections (Table 6). Among all infections, it was the UTIs where the antibiotic de-escalation intervention was most significantly implemented. On the contrary, among the abdominal and respiratory infections, it was the antibiotic change intervention due to poor progression the one most widely implemented.

Type of intervention based on the source of infection.

| DE n=64 | PP n=117 | DA n=92 | ST n=12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary | 53 (24.7) | 81 (37.7) | 65 (30.2) | 16 (7.4) |

| Abdominal | 21 (17.5) | 64 (53.3) | 33 (27.5) | 2 (1.7) |

| UTI | 20 (26.0) | 23 (29.9) | 32 (41.6) | 2 (2.6) |

| Catheter | 3 (18.8) | 3 (18.8) | 10 (62.5) | – |

| SSTI | 3 (11.5) | 8 (30.8) | 15 (57.7) | – |

| Gynecological | 1 (20) | – | 3 (60) | 1 (20) |

| Trauma. and ortho. | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50) | – |

| CNS | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50) | 2 (33.3) | – |

| Head and neck | – | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | – |

| Unknown | 8 (29.6) | 10 (37.0) | 5 (18.5) | 4 (14.8) |

DA: dose adjustment; DE: de-escalation; SSTI: skin and soft tissues infections; UTI: urinary tract infection; PP: poor progression; CNS: central nervous system; Trauma. and ortho.: traumatology and orthopedics; ST: sequential therapy.

There are two (2) important aspects that characterize the management of sepsis at our center. On the one hand, the existence of one MUSC including medical and surgical specialists. On the other hand, the existence of one computerized tool for the identification, assessment, and registry of patients with potentially severe sepsis: the PIMIS – a whole new ballgame in Spain.

Different computerized alert systems have been created to promote the identification and implementation of measures for the management of sepsis in units different than the ICU.3,5,12,13 They all share one idea – to allow an early identification and facilitate the comprehensive and intensive management of potentially critical conditions. Unlike the computerized tool developed by Ferreras et al.14 – of ER implementation, our protocol allows the activation from all hospital units.

Our analysis shows the detailed activities of every unit, while former studies only compare the differences between medical and surgical units.15 Thanks to this we know what units need healthcare improvement.

Most consultations that take place at the MUSC happen during the direct activation of the PIMIS, which shows its acceptance and recognition. Also, it is possible that the automatic generation of one set of recommendations is seen as a useful tool for the management of the patient. However, other professionals rather use the direct phone consultations. This may be due to different causes such as a greater trust in direct verbal communication; ignorance or lack of information on the very existence of the PIMIS; or distrust in technology.

Overall, the DCRs are the main mechanism of consultation, which shows that the recommendations made for the management of sepsis by parts of the MUSC are recognized and accepted. One of the main challenges that the members of the MUSC face is for their job to be accepted and recognized by specialists from their own centers. Such a requirement ensures cooperation with different medical specialties and validates the effectiveness of programs like this.

Most patients assessed through NRCs were patients from microbiological isolations. This could delay the detection of sepsis and the prescription of the adequate antibiotic treatment, since the medical assessment occurs 24h after sending the sample without having made any consultations yet on early management or empirical treatment issues. As a matter of fact, in these cases there is a significant difference in the days elapsed between the patient's admission and the assessment by the MUSC. In the future, we think that these efforts should focus on promoting early detection practices and making PIMIS more accessible.

As of today, different institutional strategies have been developed to promote the implementation of programs in an attempt to optimize antibiotic prescription16–18 since it has been reported that up to 50 per cent of all antibiotic prescriptions have been inappropriate.19 In our study, 32 per cent of all initial prescriptions were considered inappropriate. Gómez et al.3 showed that checking with a specialist in infectious diseases increased the number of appropriate treatments in initial prescriptions.

Compared to former studies, the frequency of modification of the antibiotic prescription was higher.20–22 The results are especially relevant in the surgical units.19,23,24 One of the reasons that may explain these results is the integration of the staff from the different surgical units into the MUSC. Also, the fact that the recommendations are communicated directly to the treating physician and not just detailed in the clinical history may have favored the degree of acceptance.

Also, we should stress out the high percentage of changes accepted at the ICU according to former studies.25,26 This may be due to the fact that the MUSC was created in the critical care medicine department, and many of its members come from such unit.

When it comes to the type of change recommendation made, the fact that the most common type of recommendation is due poor progression may suggest that help is wanted as a second option, when the therapeutic management is more complicated and help from a specialist in infectious diseases is deemed necessary.

It is possible that our intervention, on top of optimizing the antibiotic treatment also reduces its use since the intervention promotes antibiotic de-escalation and early sequential therapy, yet this is something that needs to be confirmed in an economic study.

Although our study shows the experience of one single center, we firmly believe that the thorough description of how our intervention works may encourage other groups to define and organize strategies in other centers.

Recently, in the last consensus document on the definitions of sepsis,27 the use of the criteria for SIRS is put into question in its diagnosis, suggesting the use of the qSOFA score as a new tool of clinical assessment. In our study period, previous recommendations were still effective and included the SIRS criteria, however, we believe that this score can facilitate the assessment and identification of severity in patients with sepsis.

One of the limitations of our study is that we did not collect the number of episodes of sepsis they did not ask our unit about. Although there is no way of knowing or comparing the prognosis of both groups, the goal of our study was to stress out the importance of organizing coordinated managements with the simultaneous implementation of measures from one multidisciplinary perspective. Hopefully, we will be able to examine the clinical variables in future studies. On the other hand, all those consultations made for diagnostic assessment purposes or reasons other than antibiotic prescription have not been collected either.

In sum, this study shows that one computerized tool like the PIMIS can be a valid strategy for the detection of sepsis. Also, the high percentage of acceptance of the recommendations made means that the activity from the MUSC is accepted and assessed positively.

Conflicts of interestsThe authors declare no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

We wish to thank the rest of the team at the multidisciplinary unit in sepsis care: J Tarradas, B Comas, S Pons, J Bauzá, A Liébana, A Villoslada, MC Pérez, C Gallego, V Fernández-Baca, M Aranda, R Morales, O Gutiérrez, J Barceló, A Llompart, R Poyo-Guerrero, D Muñiz. We also wish to thank our hospital computer experts: VM Estrada, A Hernández, F Velasco.

Please cite this article as: de Dios B, Borges M, Smith TD, del Castillo A, Socias A, Gutiérrez L, et al. Protocolo informático de manejo integral de la sepsis. Descripción de un sistema de identificación precoz. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:84–90.