One of the most important strategies of PROA in the Emergency Department (ED) is the accurate diagnosis of infection to avoid inappropriate prescription. Our objective is to evaluate patients who receive antibiotics despite not having objective data of infection.

MethodsWe carried out a cross-sectional study of patients admitted to the ED of the Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón in which it was recommended to suspend the antibiotic through the PROA. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics and 30-day follow-up were analyzed to assess readmissions and mortality.

Results145 patients were analyzed. It was recommended to suspend the antibiotic in 25. 44% of them had a diagnosis of urinary infection. The suspension recommendation was accepted by 88%. No patient died and one was readmitted.

ConclusionsAn important percentage of patients are prescribed antibiotics despite not having infection criteria, the clinical evolution after suspension of antibiotics was favorable.

Una de las estrategias más importantes de los PROA en los Servicios de Urgencias (SU) es el diagnóstico adecuado de infección para evitar la prescripción inadecuada. Nuestro objetivo es evaluar a los pacientes que reciben antibiótico a pesar de no tener datos objetivos de infección.

MétodosRealizamos un estudio transversal de los pacientes ingresados en el SU del Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón durante 2 meses (mayo del 2019 y marzo del 2021) en los que se recomendó suspender el antibiótico a través del PROA. Se analizaron las características clínicas y epidemiológicas, y el seguimiento a 30 días para valorar los reingresos y la mortalidad.

ResultadosSe analizaron 145 pacientes. Se recomendó suspender el antibiótico en 25. El 44% de ellos tenían diagnóstico de infección urinaria. La recomendación de suspensión se aceptó en el 88%. Ningún paciente falleció y uno reingresó.

ConclusionesUn porcentaje importante de pacientes tenían prescrito antibiótico a pesar de no tener criterios de infección, siendo la evolución clínica tras la de prescripción favorable.

The increase in antibiotic resistance is currently a major health problem. The widespread use of antibiotics is known to be one of the factors with the greatest impact on the generation of multiresistant microorganisms. For this reason, the creation of antibiotic stewardship programmes (ASPs) has been a priority in our health system for several years1. Emergency departments (ED) are one of the most important departments in which this type of programme can be implemented, since it is in these departments where the first doses of antibiotics are prescribed and where the diagnosis of infection is normally made2. Most ASPs are focused on the hospital setting and are based on four objectives: appropriate choice of empiric antibiotic therapy, de-escalation, dose adequacy and duration of the prescribed antibiotics. However, a fifth objective is necessary in ED ASP strategy, which is related to a proper diagnosis, considering the overdiagnosis of infections that occur in this area and needlessly increase antibiotic prescription.

The objectives of our study are to evaluate the percentage of patients with an inadequate diagnosis of infection, i.e. who receive antibiotic treatment despite the lack of objective data on infection in our hospital's ED; and understanding the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of these patients in order to implement ASP intervention strategies in the ED in the short-medium term.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study carried out in the ED of Fundación Alcorcón University Hospital, a second-level hospital with 400 planned beds. Our ED's centre is organised around two pathways; one for surgery and traumatology with a first call to surgical services and another for fundamentally medical illnesses. Accordingly, the zones are organised according to the expected wait times by the Manchester triage system: low-severity pathway (blue or green), intermediate-severity pathway (yellow) and high-severity or observation pathway (orange or red) with patient the location being flexible according to the evolution of their diseases. Patients due for admission wait in the intermediate- or high-severity pathways, depending on their pathology.

The ASP began at our hospital centre in October 2012, and it was implemented in the ED in June 2019, with recommendations made regarding antibiotic prescription in patients admitted to the intermediate- and high-severity pathways. The ASP team is multidisciplinary and is comprised of an infectious disease specialist, a microbiologist and a pharmacist. Medical history and the available results of tests and cultures are reviewed in order to make recommendations about antibiotic therapy.

Inadequate empiric treatment is considered to be that which does not conform to our centre's clinical guidelines, and patients in whom there are no objective data of infection when the clinical history and complementary tests are reviewed are considered candidates for suspending antibiotic therapy. These recommendations by the ASP team are made to the prescribing physician responsible for the patient in an individualised, non-imposing, face-to-face and written manner.

In our study, we analysed patients admitted to the ED in the morning timetable over two months (May 2019 and March 2021), who received antibiotic treatment and in whom, through the ASP, the suspension of antibiotic therapy was recommended.

The medical records of the patients attended to were reviewed, the clinical and epidemiological characteristics were examined and a 30-day follow-up was carried out. During follow-up, the requirement for the initiation of antibiotics, the number of readmissions due to infection and infection-related mortality were assessed.

The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón [Alcorcón Foundation University Hospital] Clinical Research Ethics Committee. Age is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and the rest of the variables (qualitative) as percentages. Confidence intervals were calculated using Wilson's method.

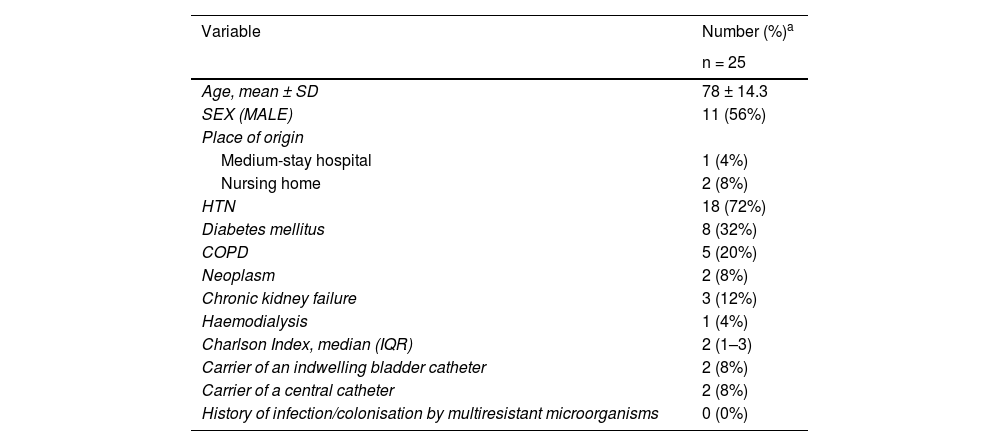

ResultsA total of 145 patients who attended the ED in May 2019 and March 2021 were analysed (25% of the patients admitted to the intermediate- and high-severity pathways). The empiric antibiotic treatment started was inadequate in 65 patients (45%, 95% CI: 37%–53%). Of these, it was recommended that the antibiotic be suspended in 25 patients (17.2%, 95% CI: 12%–24.2%). Slightly more than half of these patients (56%) were male, with a mean age of 78 years (SD 14.3), and 12.1% came from a residential care facility or medium-stay hospital. The rest of the clinical characteristics, comorbidities, presence of medical devices, history of infection or colonisation by multiresistant microorganisms are shown in Table 1.

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the patients in whom the suspension of antibiotic therapy was recommended.

| Variable | Number (%)a |

|---|---|

| n = 25 | |

| Age, mean ± SD | 78 ± 14.3 |

| SEX (MALE) | 11 (56%) |

| Place of origin | |

| Medium-stay hospital | 1 (4%) |

| Nursing home | 2 (8%) |

| HTN | 18 (72%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (32%) |

| COPD | 5 (20%) |

| Neoplasm | 2 (8%) |

| Chronic kidney failure | 3 (12%) |

| Haemodialysis | 1 (4%) |

| Charlson Index, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) |

| Carrier of an indwelling bladder catheter | 2 (8%) |

| Carrier of a central catheter | 2 (8%) |

| History of infection/colonisation by multiresistant microorganisms | 0 (0%) |

Of the 25 patients in whom antibiotic the suspension was recommended, 44% (11/25) had a diagnosis of urinary infection and 28% (7/25) a diagnosis of respiratory infection, with blood cultures performed in 24% and urine culture in 68% of these patients. The recommendation to suspend the antibiotic was accepted in 88% of the cases (22/25). The most frequent antibiotic prescription was ceftriaxone (60%), followed by amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (24%), piperacillin/tazobactam (12%), quinolones (4%) and carbapenem (4%).

Fourteen of the 25 patients studied (56%) required hospital admission. The most frequent diagnoses on admission were bleeding (3/14), neurological symptoms (4/14) such as seizures, benzodiazepine intoxication or transient ischaemic attack, heart failure (2/14) and heart block in one patient.

In the 30-day follow-up, of the 22 patients in whom antibiotic treatment was suspended, none died, one patient was readmitted for the same initial reason for which they came to the Emergency Department (a non-infectious exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) and none of the patients needed to restart antibiotic therapy.

DiscussionSince the World Health Organization’s alert in 2014 on antibiotic resistance, many health centres have implemented measures to contend with this serious health problem3. ASPs were conceived with the intention of developing interventions that reduce the inappropriate use of antimicrobials, and their benefit has been demonstrated in numerous studies4. However, most ASP programmes are carried out in hospitalised patients and the studies conducted in the ED are variable, with poorly standardised criteria1,5.

As stated in the review carried out by May et al.5, one of the main aspects of ASPs in the ED is making an adequate clinical diagnosis, without studies that analyse the clinical evolution in patients in whom the antibiotic is withdrawn due to a low suspicion of infection.

The findings in our study regarding the inappropriate prescription of antibiotics in the ED (45%) are similar to those described in the literature6–9. As in other studies, the most frequent presumptive diagnosis in our series was urinary and respiratory infection7, and the most commonly used antibiotics are β-lactams (cephalosporins and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid).

One of the keys to the proper functioning of ASPs in the ED is to achieve a high percentage of acceptance of recommendation. At our centre it was 88%, higher than the 80% reported by other studies10–12. We believe that this high level of acceptance of the recommendations may be due to several factors. First, the integration of the ASP into daily care practice in the ED; secondly, the participation of pharmacists, infectious disease experts and microbiologists in the ASP team1, and, finally, that the recommendations are made individually to the prescribing doctor, in person and in writing, and in a non-imposing manner.

In our cohort, the suspension of antibiotic therapy in patients with a low risk of infection appears to be safe, since there were no readmissions or deaths due to infectious disease during follow-up. In addition to the fact that there were no deaths due to infectious causes, taking into account the limitations of mortality as an important variable in our study, at one month of follow-up, none of the 22 patients in whom the antibiotic was withdrawn presented signs of infection or required the resumption of antibiotic treatment.

Our study has several limitations, as well as strengths. One of the limitations is the small sample size, as it was an observational study and the follow-up was short-term. In addition, given the healthcare characteristics of the ED, with a high turnover of professionals, our programme does not involve ED professionals, which could be beneficial in the future. However, to our knowledge, it is one of the few studies in which the cohort of patients in whom antibiotic treatment is withdrawn due to a low suspicion of infection has been evaluated without taking only analytical parameters into account, also demonstrating that these patients do not present higher morbidity and mortality in the short term.

In conclusion, in our series, an antibiotic had been prescribed to a significant percentage of patients despite their not having infection criteria. These results allow us to create improvement strategies and support us in recommending the safe withdrawal of antibiotics in the ED when there are no objective infection data. More studies are needed to address the role of antibiotic prescription and clinical follow-up in the medium and long term in patients evaluated in the Emergency Department with a low suspicion of infection, as well as to validate scales that will help clinicians to stratify the risk of infection.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Special thanks to the Pharmacy, Microbiology and Internal Medicine Services for their work regarding our centre’s ASP.