To describe the clinical experience with dalbavancin in the treatment of diabetic foot infection in a multidisciplinary unit of a second level hospital.

MethodsA retrospective, descriptive study was made with all patients with diabetic foot infection treated with dalbavancin in the Diabetic Foot Unit of Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, covering the period from September 2016 to December 2019. Demographic parameters and comorbidities, characteristics of the infection and treatment with dalbavancin were recorded. The cure rate is estimated at 90 days after finishing the treatment.

ResultsA total of 23 patients with diabetic foot infection (osteomyelitis) started treatment with dalbavancin, 19 were men and the mean age was 65 years. The microorganisms most frequently isolated for the indication of treatment with dalbavancin were Staphylococcus aureus (11) and Corynebacterium striatum (7). Dalbavancin was used as a second choice therapy in 22 cases, in 11 due to toxicity from other antibiotics. The median duration of treatment was 5 (4–7) weeks; the most frequent dose of dalbavancin (8 patients) was 1000 mg followed by 500 mg weekly for 5 weeks. 3 patients presented mild side effects (nausea and gastrointestinal discomfort). At 90 days after completion of dalbavancin therapy, 87% (20) of the patients were cured (95% CI: 65.2%–94.52%).

ConclusionPatients with osteomyelitis due to gram-positive microorganisms who received as part of the multidisciplinary antibiotic treatment with dalbavancin, had a high rate of cure with adequate tolerance and few side effects. Dalbavancin offers a safe alternative in treating deep diabetic foot infection.

Describir la experiencia clínica con dalbavancina en el tratamiento de la infección de pie diabético en una unidad multidisciplinar de un hospital de segundo nivel.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo retrospectivo de pacientes con infección de pie diabético tratados con dalbavancina en la Unidad de Pie Diabético del Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón de septiembre de 2016 a diciembre de 2019. Se recogieron parámetros demográficos y comorbilidades, características de la infección y del tratamiento con dalbavancina. Se estima la tasa de curación a los 90 días tras finalizar el tratamiento.

ResultadosUn total de 23 pacientes con infección de pie diabético (osteomielitis) fueron tratados con dalbavancina, 19 eran hombres con una edad media de 65 años. Los microorganismos más frecuentemente aislados fueron Staphylococcus aureus (11) y Corynebacterium striatum (7). En 22 casos se usó dalbavancina como terapia de segunda elección, en 11 debido a toxicidad de otros antibióticos. La mediana de duración del tratamiento fue de 5 (4–7) semanas; la dosis más frecuente de dalbavancina (8 pacientes) fue de 1000 mg seguido de 500 mg semanales durante 5 semanas. 3 pacientes presentaron efectos secundarios leves (náuseas y molestias gastrointestinales). A los 90 días de finalizar el tratamiento, 87% (20) de los pacientes se curaron (IC95%: 65.2%–94.52%).

ConclusiónLos pacientes con osteomielitis por microorgamismos gram positivos que recibieron como parte del tratamiento multidisciplinar antibioterapia con dalbavancina, tuvieron una elevada tasa de curación con una adecuada tolerancia y escasos efectos secundarios. Dalbavancina ofrece una alternativa segura en el tratamiento de la infección profunda de pie diabético.

Diabetic foot infection is a complication experienced by up to 15% of diabetic patients over the course of their lives1. When associated with ischaemia, it represents the most common cause of non-traumatic lower-extremity amputation, hospital admission and decreased quality of life in these patients2. This infection is highly complex given that multiple factors (presence of osteomyelitis, degree of ischaemia and associated comorbidity) determine its course, and suitable management requires multidisciplinary teams. In acute infections, an incidence of Staphylococcus aureus3 around 43% with an elevated prevalence of methicillin resistance has been reported4. Polymicrobial flora, including anaerobic micro-organisms, enterococci and Gram-negative bacilli, is often involved in chronic infection3. Dalbavancin, a glycopeptide, is a recent addition to treatment options for infections caused by Gram-positive micro-organisms with unique pharmacokinetic characteristics. Clinical studies have demonstrated its efficacy and safety in the treatment of skin and soft-tissue infections5, as well as in osteoarticular infection6. Although there are no studies on the efficacy of dalbavancin in diabetic foot infection, there are publications comparing its efficacy in the treatment of osteomyelitis versus the usual treatment with a cure rate of 97%7, as well as publications on clinical experience with dalbavancin in treating osteomyelitis with cure rates of 65%8. The objective of our study is to report clinical experience with dalbavancin treatment and the safety thereof in patients with deep diabetic foot infection (osteomyelitis).

Materials and methodsThis was a retrospective, descriptive study conducted on the Diabetic Foot Unit at Hospital Fundación Alcorcón [Alcorcón Foundation Hospital], a secondary hospital with 400 planned hospital beds. The Diabetic Foot Unit at this hospital is multidisciplinary, made up of professionals in vascular surgery, podiatry, infectious diseases and specialised nursing. Patients receive outpatient follow-up in which skin-care recommendations are made, dead or infected tissue is offloaded to prevent ulcers and superinfection of ulcers, and the need for and possibility of revascularisation are weighed in ischaemic patients. When a patient has an infection, the infection disease specialist is contacted to start antibiotic therapy. Around 1000 patients are seen each year on an outpatient basis; of them, 17.5% have infection.

Between September 2016 and December 2019, a total of 353 patients with diabetic foot infection were seen. All patients with a diagnosis of osteomyelitis who had received dalbavancin during this period were included.

Patients were considered candidates for receiving dalbavancin if they had signs of infection according to the criteria of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)4 caused by Gram-positive micro-organisms and one or more of the following characteristics: treatment failure, toxicity or drug interactions with previously used antibiotics (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, quinolones, oxazolidinones or tetracyclines). The decision to start treatment with dalbavancin, as well as the dose used, was made by the infectious disease specialist on the Diabetic Foot Unit. The dose used varied over the course of the study period based on experience and scientific evidence. In general, the drug was administered at a medical day hospital.

A cure was confirmed when the lesion remained healed 90 days after primary wound closure, or if intraoperative culture came back negative after at least one dose of dalbavancin in patients who required subsequent amputation. Treatment failure was defined as prior antibiotic therapy with persistent signs of infection according to the IDSA criteria4, persistence of a positive probe-to-bone (PTB) test9,10 and/or lesion non-healing. On our unit, osteomyelitis is diagnosed with a combination of a positive PTB test and X-ray with or without bone culture11 (collected according to the recommendations of the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot [IWGDF] guidelines)12.

The following patient data were collected: demographic variables (age and sex); comorbidity variables needed to calculate the Charlson Index13 and the McCabe score14; and names and numbers of drugs in their usual treatment to determine whether they had polypharmacy (≥5 drugs)15 and/or were being treated with drugs on the “Lista de medicamentos de alto riesgo en pacientes crónicos” [List of High-Risk Medicines in Patients with Chronic Disease] (Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality)16 in order to prevent or predict possible side effects due to interactions.

The following infection data were recorded: degree (mild, moderate or severe) according to the IDSA classification4, type of impairment (neuropathic, ischaemic or mixed), method for diagnosing osteomyelitis (bone culture, PTB test or plain X-ray), whether the infection was monomicrobial or polymicrobial, microbiological isolation in bone culture (in polymicrobial infections, dalbavancin-sensitive micro-organisms were collected). Other data collected were: lesion location, need for amputation and type of amputation, whether or not revascularisation was performed and what type, and need for negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT), as indicators of infection complexity. Finally, the antibiotic therapy used before dalbavancin was started, the reason why it was indicated, the dose and treatment duration, and any adverse reactions and incidents that occurred during its administration were also collected.

The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki17, approved by the Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón [Alcorcón Foundation University Hospital] Independent Ethics Committee (18/68) and classified by the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios [Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices] (GNJ-DAL-2020-01).

Results are expressed in terms of mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range for continuous variables, and in terms of percentages for qualitative variables. Confidence intervals were calculated using Wilson’s method.

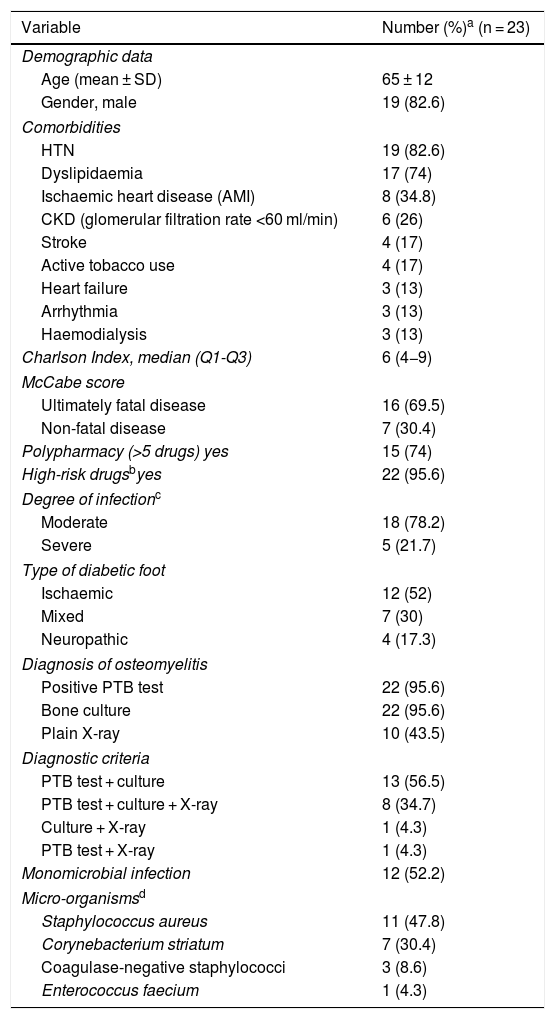

ResultsDemographic and clinical dataA total of 23 patients with diabetic foot infection started treatment with dalbavancin. Variables in relation to demographics, comorbidity and infection type and severity, as well as other baseline characteristics, are shown in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort.

| Variable | Number (%)a (n = 23) |

|---|---|

| Demographic data | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 65 ± 12 |

| Gender, male | 19 (82.6) |

| Comorbidities | |

| HTN | 19 (82.6) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 17 (74) |

| Ischaemic heart disease (AMI) | 8 (34.8) |

| CKD (glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min) | 6 (26) |

| Stroke | 4 (17) |

| Active tobacco use | 4 (17) |

| Heart failure | 3 (13) |

| Arrhythmia | 3 (13) |

| Haemodialysis | 3 (13) |

| Charlson Index, median (Q1-Q3) | 6 (4−9) |

| McCabe score | |

| Ultimately fatal disease | 16 (69.5) |

| Non-fatal disease | 7 (30.4) |

| Polypharmacy (>5 drugs) yes | 15 (74) |

| High-risk drugsbyes | 22 (95.6) |

| Degree of infectionc | |

| Moderate | 18 (78.2) |

| Severe | 5 (21.7) |

| Type of diabetic foot | |

| Ischaemic | 12 (52) |

| Mixed | 7 (30) |

| Neuropathic | 4 (17.3) |

| Diagnosis of osteomyelitis | |

| Positive PTB test | 22 (95.6) |

| Bone culture | 22 (95.6) |

| Plain X-ray | 10 (43.5) |

| Diagnostic criteria | |

| PTB test + culture | 13 (56.5) |

| PTB test + culture + X-ray | 8 (34.7) |

| Culture + X-ray | 1 (4.3) |

| PTB test + X-ray | 1 (4.3) |

| Monomicrobial infection | 12 (52.2) |

| Micro-organismsd | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 11 (47.8) |

| Corynebacterium striatum | 7 (30.4) |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 3 (8.6) |

| Enterococcus faecium | 1 (4.3) |

AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CKD: chronic kidney disease; HTN: hypertension; PTB: probe-to-bone; SD: standard deviation.

Dalbavancin was used in 22 cases (95.6%) as a second-line treatment; in 11 cases (47.8%) due to toxicity with other antibiotics and in eight cases (34.8%) due to prior antibiotic treatment failure. In two patients (8.6%), it was used in a situation of tedizolid shortage when linezolid had not been tolerated, in another two cases (8%) it was used to prevent interactions and in one case (4.3%) it was used to hasten the patient's discharge home.

Regarding toxicity caused by prior antibiotics, the most common type was gastrointestinal toxicity, caused by linezolid in five patients (21.7%) and clindamycin in three patients (13%). The second most common type was haematological toxicity, due to linezolid in four patients (17.4%).

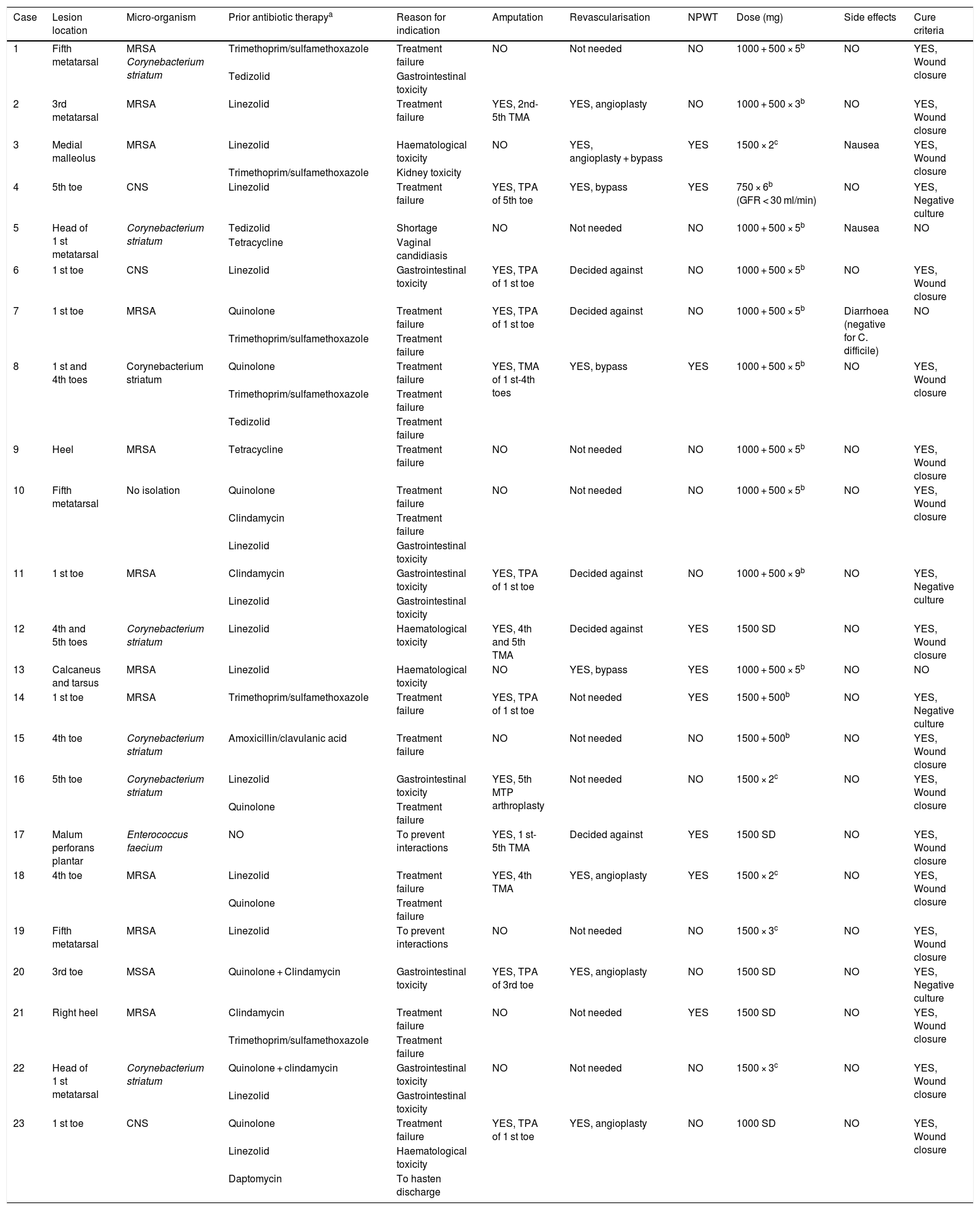

The median duration of treatment with dalbavancin was five (four to seven) weeks; in eight patients (34.8%), the dose of dalbavancin administered was 1000 mg followed by 500 mg weekly for five weeks, followed in five cases (21.7%) by two doses of 1500 mg two weeks apart. In all cases except for one, dalbavancin was administered on an outpatient basis. Thirteen patients (56.5%) underwent amputation in addition to receiving antibiotic therapy; in all cases, amputation was minor (below the ankle). Revascularisation was indicated in 13 patients (56.5%) but ultimately decided against in five (38.4%). All these data are listed by patient in Table 2.

Specific data by patient and outcomes of treatment with dalbavancin.

| Case | Lesion location | Micro-organism | Prior antibiotic therapya | Reason for indication | Amputation | Revascularisation | NPWT | Dose (mg) | Side effects | Cure criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fifth metatarsal | MRSA Corynebacterium striatum | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Treatment failure | NO | Not needed | NO | 1000 + 500 × 5b | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| Tedizolid | Gastrointestinal toxicity | |||||||||

| 2 | 3rd metatarsal | MRSA | Linezolid | Treatment failure | YES, 2nd-5th TMA | YES, angioplasty | NO | 1000 + 500 × 3b | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| 3 | Medial malleolus | MRSA | Linezolid | Haematological toxicity | NO | YES, angioplasty + bypass | YES | 1500 × 2c | Nausea | YES, Wound closure |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Kidney toxicity | |||||||||

| 4 | 5th toe | CNS | Linezolid | Treatment failure | YES, TPA of 5th toe | YES, bypass | YES | 750 × 6b (GFR < 30 ml/min) | NO | YES, Negative culture |

| 5 | Head of 1 st metatarsal | Corynebacterium striatum | Tedizolid | Shortage | NO | Not needed | NO | 1000 + 500 × 5b | Nausea | NO |

| Tetracycline | Vaginal candidiasis | |||||||||

| 6 | 1 st toe | CNS | Linezolid | Gastrointestinal toxicity | YES, TPA of 1 st toe | Decided against | NO | 1000 + 500 × 5b | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| 7 | 1 st toe | MRSA | Quinolone | Treatment failure | YES, TPA of 1 st toe | Decided against | NO | 1000 + 500 × 5b | Diarrhoea (negative for C. difficile) | NO |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Treatment failure | |||||||||

| 8 | 1 st and 4th toes | Corynebacterium striatum | Quinolone | Treatment failure | YES, TMA of 1 st-4th toes | YES, bypass | YES | 1000 + 500 × 5b | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Treatment failure | |||||||||

| Tedizolid | Treatment failure | |||||||||

| 9 | Heel | MRSA | Tetracycline | Treatment failure | NO | Not needed | NO | 1000 + 500 × 5b | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| 10 | Fifth metatarsal | No isolation | Quinolone | Treatment failure | NO | Not needed | NO | 1000 + 500 × 5b | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| Clindamycin | Treatment failure | |||||||||

| Linezolid | Gastrointestinal toxicity | |||||||||

| 11 | 1 st toe | MRSA | Clindamycin | Gastrointestinal toxicity | YES, TPA of 1 st toe | Decided against | NO | 1000 + 500 × 9b | NO | YES, Negative culture |

| Linezolid | Gastrointestinal toxicity | |||||||||

| 12 | 4th and 5th toes | Corynebacterium striatum | Linezolid | Haematological toxicity | YES, 4th and 5th TMA | Decided against | YES | 1500 SD | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| 13 | Calcaneus and tarsus | MRSA | Linezolid | Haematological toxicity | NO | YES, bypass | YES | 1000 + 500 × 5b | NO | NO |

| 14 | 1 st toe | MRSA | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Treatment failure | YES, TPA of 1 st toe | Not needed | YES | 1500 + 500b | NO | YES, Negative culture |

| 15 | 4th toe | Corynebacterium striatum | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | Treatment failure | NO | Not needed | NO | 1500 + 500b | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| 16 | 5th toe | Corynebacterium striatum | Linezolid | Gastrointestinal toxicity | YES, 5th MTP arthroplasty | Not needed | NO | 1500 × 2c | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| Quinolone | Treatment failure | |||||||||

| 17 | Malum perforans plantar | Enterococcus faecium | NO | To prevent interactions | YES, 1 st-5th TMA | Decided against | YES | 1500 SD | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| 18 | 4th toe | MRSA | Linezolid | Treatment failure | YES, 4th TMA | YES, angioplasty | YES | 1500 × 2c | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| Quinolone | Treatment failure | |||||||||

| 19 | Fifth metatarsal | MRSA | Linezolid | To prevent interactions | NO | Not needed | NO | 1500 × 3c | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| 20 | 3rd toe | MSSA | Quinolone + Clindamycin | Gastrointestinal toxicity | YES, TPA of 3rd toe | YES, angioplasty | NO | 1500 SD | NO | YES, Negative culture |

| 21 | Right heel | MRSA | Clindamycin | Treatment failure | NO | Not needed | YES | 1500 SD | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Treatment failure | |||||||||

| 22 | Head of 1 st metatarsal | Corynebacterium striatum | Quinolone + clindamycin | Gastrointestinal toxicity | NO | Not needed | NO | 1500 × 3c | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| Linezolid | Gastrointestinal toxicity | |||||||||

| 23 | 1 st toe | CNS | Quinolone | Treatment failure | YES, TPA of 1 st toe | YES, angioplasty | NO | 1000 SD | NO | YES, Wound closure |

| Linezolid | Haematological toxicity | |||||||||

| Daptomycin | To hasten discharge |

CKD: chronic kidney disease; CNS: coagulase-negative staphylococci; GFR: glomerular filtration rate; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA: methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; MTP: metatarsophalangeal; NPWT: negative-pressure wound therapy; TMA: transmetatarsal amputation; TPA: transphalangeal amputation; SD: single dose.

Ninety days after completing treatment with dalbavancin, 20 patients (87%) were cured (95% CI: 65.2–94.52%).

One patient had a single episode of hyperglycaemia during dalbavancin administration as the diluent used was a dextrose solution. Three patients (13%) presented mild side effects in the form of nausea and gastrointestinal discomfort that did not require the drug to be suspended.

DiscussionThis study represents the first scientific paper on clinical experience with the use of dalbavancin in diabetic foot infection with osteomyelitis. In our study, dalbavancin was used in patients with a high rate of comorbidity, polypharmacy and a high risk of drug interactions. The majority of patients (78.2%) had a moderate degree of infection requiring a combination of medical and surgical treatment (in 56.5%, minor amputation was performed as part of treatment) and had previously received antibiotic therapy with a poor course or toxicity. Dalbavancin was well tolerated, and combined with routine surgical management, had a high cure rate — 87% (95% CI: 64.15%–93.32%) — 90 days after completion of treatment.

Diabetic foot infection is a complex infection with multiple factors influencing its course. These patients have several particular characteristics that suggest that they might benefit from treatment with dalbavancin.

It should be noted that patients with diabetic foot infection usually have polypathology and are polymedicated (the members of our cohort had a median Charlson Index of 6 points, 74% of them were polymedicated and 95.6% of them took drugs considered high risk). This can lead to drug interactions18; decrease serum antibiotic levels; worsen adherence to treatment19, resulting in treatment failure; and enhance antibiotic toxicity. In our study, 47.8% of patients were switched to dalbavancin for the latter reason, showing good tolerance, with few and mild side effects and 100% adherence to treatment. Treatment with dalbavancin, due to the drug's peculiar pharmacokinetics and posology, can be administered once weekly or once every two weeks; this promotes treatment adherence. The regimen of dalbavancin administration that we used most often was 1000 mg followed by 500 mg weekly up to six weeks. The use of different administration regimens during the study made it difficult to draw conclusions on the most advisable dosage regimen. However, in our experience, administration of 1500 mg every two weeks, based on pharmacokinetic studies in which a high concentration in bone was maintained 14 days from administration20, seems to us a good option for this patient group.

Part of the complexity of such infections lies in the fact that they are chronic with frequent reinfection requiring repeated (and long) cycles of antibiotic therapy, thus contributing to a high prevalence of multidrug-resistant micro-organisms21. In diabetic foot infection, the most significant pathogen is S. aureus, with a prevalence of methicillin resistance of up to 38%, depending on the series22 (47.8% in our study). Corynebacterium striatum merits special mention. Long considered a colonising micro-organism in chronic infections, it is currently thought to be an emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen in immunosuppressed patients and related to risk factors such as diabetes23 and prior antibiotic therapy24. It should be considered as a pathogen when there are signs of infection and the lesion follows a poor clinical course25. According to these criteria, our cohort had a high prevalence of C. striatum infection (30.4%). Dalbavancin has demonstrated advantages in osteomyelitis caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus26; however, experience with dalbavancin activity against C. striatum is limited. In our study, six of the seven patients who presented osteomyelitis due to C. striatum and received dalbavancin as part of their medical and surgical treatment met the criteria for a cure.

It is important to note that we are talking about dalbavancin as an alternative antibiotic treatment in patients who, for the different reasons mentioned above, have no other option in terms of oral antibiotic therapy, such that it enables continuation of outpatient management of osteomyelitis that would otherwise require hospital admission or daily hospital visits for six weeks. In our study, the majority of patients (n = 18) had a moderate infection requiring a combination of medical and surgical treatment: 13 patients required amputation (which was minor in all cases), and eight required revascularisation. This combination showed a high 90-day cure rate (87% [95% CI: 65.2%–94.52%]).

Our study had the limitations inherent to a retrospective, observational study with a small sample size. However, given the good tolerance seen in all cases and the high cure rate, we believe that dalbavancin, in combination with routine surgical management, is a suitable treatment option in patients with polypathology who are polymedicated with diabetic foot osteomyelitis caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-positive micro-organisms.

FundingThis study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there were no conflicts of interest.

G. Navarro-Jiménez and C. Fuentes-Santos have contributed equally to the Article (conception, design, data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript), and share first authorship.

Please cite this article as: Navarro-Jiménez G, Fuentes-Santos C, Moreno-Núñez L, Alfayate-García J, Campelo-Gutierrez C, Sanz-Márquez S, et al. Experiencia con el uso de dalbavancina en la infección profunda de pie diabético. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:296–301.