To estimate the burden of nosocomial infections induced by carbapenem resistant Gram-negative (CRGN) pathogens in Spain, focusing on both the clinical and economic impact.

MethodsThe burden of disease was estimated using data from 2017 according to the availability of data sources. The impact, both clinical and economic, of the most frequent CRGN nosocomial infections (those produced by Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonasaeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii) was analysed. Incidence and mortality of CRGN nosocomial infections were estimated, as well as the direct and indirect costs produced by this health problem.

ResultsApproximately 376,346 patients are believed to have suffered a nosocomial infection in Spain in 2017; 3.2% of them due to CRGN bacilli. Infections by carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa produced the highest mortality rates (2578 deaths) when compared with A. baumannii (1571) and K. pneumoniae (415). Total economic costs of CRGN nosocomial infections in Spain were estimated to be €472 million in 2017, with 83% of the total cost caused by direct costs.

ConclusionCRGN nosocomial infections have a high clinical impact on patients’ lives, high mortality rates, and represent one of the hospitalisation episodes with the most associated costs. Efforts should be focussed to implement preventive policies in order to avoid infections due to CRGN pathogens and the resulting burden, and to reduce direct costs due to morbimortality, specifically in those infections produced by P. aeruginosa.

Estimar la carga de las infecciones nosocomiales inducidas por patógenos gramnegativos resistentes a carbapenemas (GNRC) en España, focalizada tanto en el impacto clínico como en el económico.

MétodosLa carga de la enfermedad se estimó utilizando datos del año 2017, de acuerdo con la disponibilidad de los mismos en bases de datos. Se analizó el impacto, tanto clínico como económico, de las infecciones nosocomiales GNRC más habituales (causadas por Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa y Acinetobacter baumannii). Se estimaron la incidencia y la mortalidad de las infecciones nosocomiales GNRC, así como los costes directos e indirectos derivados de este problema de salud.

ResultadosAproximadamente 376.346 pacientes podrían haber sufrido una infección nosocomial en España durante el año 2017; siendo el 3,2% de ellas producidas por bacilos GNRC. Las infecciones causadas por P. aeruginosa resistente a carbapenemas produjeron las mayores tasas de mortalidad (2.578 muertes) en comparación con A. baumannii (1.571) y K. pneumoniae (415). Los costes económicos totales de las infecciones nosocomiales producidas por GNRC en España se estimaron en 472 M€ en 2017, siendo el 83% del coste total representado por los costes directos.

ConclusiónLas infecciones nosocomiales producidas por GNRC tienen un gran impacto en la vida de los pacientes, altas tasas de mortalidad y representan uno de los episodios de hospitalización con más costes hospitalarios asociados. Se deben focalizar los esfuerzos en políticas de prevención para evitar las infecciones por patógenos GNRC y su carga, así como para reducir los costes directos producidos por la morbimortalidad, concretamente en aquellas infecciones producidas por P. aeruginosa.

Developing and spreading of multi-drug resistant (MDR) bacteria has been considered a serious threat to global public health by World Health Organisation (WHO), United Nations (UN) and European Union (EU), amongst other organisations.1 It is estimated that up to 10 million people worldwide would die due to MDR bacteria in 2050.2 In addition, approximately 30% of hospitalised patients in intensive care units (ICU) would be affected by at least one episode of nosocomial infection.3

In developed countries, nosocomial infections affect between 5% and 15% of hospitalised patients4 being respiratory, surgical, urinary and vascular catheter-related bacteraemia the most frequent infection sites.5 In 2015, it was estimated that about 33,000 people die each year as a direct consequence of an infection due to bacteria resistant to antibiotics in the EU.6 Moreover, there are more than 4 million people suffering from nosocomial infections every year in Europe, compared to 1.7 million in USA.5

The prevalence of nosocomial infections varies in a range from 3.5% to 14.8% in Europe, reaching the highest peaks in the Mediterranean countries.4 In Spain, the epidemiology of nosocomial infections is analysed annually by the study of prevalence of nosocomial infections in Spain (EPINE). According to EPINE data, 7.7% of patients had a nosocomial infection in Spain in 2017.7 The infections with the highest prevalence were surgical infections (25.0%), respiratory tract infections (19.8%), urinary tract infections (19.3%) and bacteraemia (15.1%). Moreover, Spain is one of the countries with the highest consumption of antibiotics in the EU, as well as one of the first on MDR bacterial infections in Europe.8 National and regional measures are being taken to solve this public health problem. Recently, a new one-health National Plan against Resistance to Antibiotics (PRAN), was approved for the period 2019–2021.9

Amongst the existent types of bacterial resistances, carbapenem-resistant gramnegative (CRGN) pathogens are currently posing a concern around the world. Carbapenem resistance (CR) in gramnegative (GN) pathogens is the main contributing factor for MDR, since some of these strains are also resistant to other antimicrobial agents.10 Its rapid spread is causing serious outbreaks and limiting treatment options.11 CRGN nosocomial pathogens are expecting to evolve accumulating more CR mechanisms and to other antimicrobial agents, and therefore this health issue would be further aggravated in the future.11

On the other hand, burden of disease (BoD) studies analyse the impact of a disease or health condition (both on a clinical and an economic level) upon populations and might help to improve global public health policies and decision-making. To the best knowledge of the authors, there are few studies that analysed the burden of CRGN nosocomial infections although the clinical and economic approach of BoD studies make them appropriate to analyse this public health problem.12 Therefore, this study aimed to calculate the burden of nosocomial infections due to CRGN pathogens in Spain with existing published available information.

MethodsThis study focuses on those infections acquired during hospital stays because they have a high impact on the survival and well-being of the patients who suffer them and pose an increasing challenge to public health. Therefore, community-acquired infections were excluded. The clinical impact was calculated based on published available data on the epidemiology and mortality of CRGN nosocomial infections, and the economic impact based on the direct and indirect costs.

Clinical impactThe clinical impact of CRGN nosocomial infections was measured through their prevalence (total number of patients with CRGN nosocomial infection in Spain in 2017), mortality (total number of attributable deaths due to CRGN nosocomial infection) and Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) that represent the number of healthy life years lost due to CRGN nosocomial infections.

Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii were selected as the pathogens of interest for the study because they showed the highest rates of CR isolates in Spain in 2017. Although the prevalence of nosocomial infections caused by Escherichia coli is higher than the prevalence of K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii (15.8% versus 8%, 9.6% and 1.8%, respectively), its prevalence of CR was below 0.1% according to the ECDC data and therefore, it was not included in the study.13

The total number of patients with CRGN nosocomial infections was estimated in three steps. First, the total number of hospital discharges was multiplied by the prevalence of nosocomial infections to obtain the number of patients who had at least one nosocomial infection in Spain in 2017. Second, this number was multiplied by the percentage of GN infections produced by K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii to obtain the number of patients who had a nosocomial infection caused by these pathogens. The total number of patients who suffered a nosocomial infection produced by CRGN pathogens was obtained multiplying the number of patients with nosocomial infection caused by GN pathogens by the percentage of CR of these pathogens:

Estimated number of patients with CRGN nosocomial infections in Spain in 2017=hospital discharges in Spain in 2017×Prevalence of nosocomial infections (%)×Percentage of GN (%)×Percentage of CRGN nosocomial infections.

Mortality caused by CRGN nosocomial infections was calculated by multiplying the percentage of fatality cases due to CRGN pathogens and the estimated number of patients with CRGN nosocomial infections:

Estimated mortality due to CRGN nosocomial infections in Spain in 2017=Percentage of fatality cases due to CRGN pathogens×Estimated number of patients with CRGN nosocomial infections in Spain in 2017.

Data was retrieved from different sources because of its availability. The total number of hospital discharges was obtained from the Spanish Statistical Office (INE) that includes discharges due to improvement or cure of the disease or health condition, death or transfer to another hospital facility.14 Prevalence of nosocomial infections and the percentage of GN infections were obtained from the EPINE 2017 study. The EPINE study is an epidemiology study that includes data from 313 Spanish voluntary hospitals (61,673 patients) and it is performed since 1990 by the Spanish Society of Preventive Medicine, Public Health and Hygiene (SEMPSPH).7 Finally, carbapenem resistance information by type of GN pathogen was obtained from Atlas of Infectious Diseases in the ECDC web-page and reports.15 Mortality data was retrieved from Cassini et al. (2019) who estimated the percentage of attributable fatality cases due to CRGN pathogens from an international systematic literature review.6 DALYs caused by each type of pathogen were obtained from the supplementary appendix of Cassini et al. (2019).16

Economic impactA social perspective was considered, meaning that not only the relevant costs for the Spanish National Health System (NHS) were included but also the costs relevant for society, such as productivity losses. Total economic impact was estimated as the sum of direct and indirect costs produced by CRGN nosocomial infections.

Direct costs are usually defined as the costs related to the hospital management (health professionals, administrative work, hospital facilities, among others) and treatment of CRGN nosocomial infections. In this study, direct costs were obtained by multiplying the estimated number of patients with CRGN nosocomial infections in Spain according to each type of pathogen and the hospital costs of hospitalisation episode of CRGN nosocomial infections by type of pathogen, obtained from Riu et al. (2016).17 All costs were updated to 2017 prices by using the Consumer Price Index:18

Direct costs of nosocomial infections due to CRGN pathogens in Spain=Estimated number of patients with CRGN nosocomial infections in Spain×Hospital costs of hospitalisation episode of CRGN nosocomial infections×Consumer Price Index 2017.

Indirect costs can be defined as those related to productivity loss, which included the costs of premature mortality, temporary and permanent disability, and informal care. In this study, only the costs of premature mortality and temporary disability were considered. Indirect costs were calculated by adding the costs of loss productivity due to premature mortality to the costs of loss productivity due to temporary disability caused by CRGN nosocomial infections.

Premature mortality costs were calculated as follows: first, it was assumed that the distribution of the Spanish population by age was proportional to the number of fatality cases attributable to CRGN infections. Second, Spanish life expectancy by age range obtained from the INE19 was subtracted to the number of mortality cases attributable to CRGN nosocomial infections by age to estimate the total number of years of life lost per age range. Third, to estimate the total number of years of working life lost, the total number of years of life loss of those patients in working age (it was considered that the minimum working age in Spain is 16 years old and that retirement age is 65 years old) were added. This was multiplied by the number of patients in working age dead by CRGN infection, the average salary in euros and the employment rate by age range from INE 2017:20

Productive years lost due to premature mortality=Mortality due to CRGN infections per age range−Retirement age in Spain (considered 65 years old).

Costs of loss of productivity due to premature mortality=Total number of patients in working age dead by CRGN infection×Productive years lost due to premature mortality×Average salary in euros×Employment rate by age range.

The costs of productivity loss due to temporary disability were estimated as following: first, the number of working-age patients with CRGN nosocomial infection according to type of pathogen (excluding patients who had already died) was multiplied by the duration of hospital stays attributable to CRGN pathogens obtained from Cassini et al. (2019),6 the daily average salary in euros and the employment rate by age range obtained from INE 2017.21

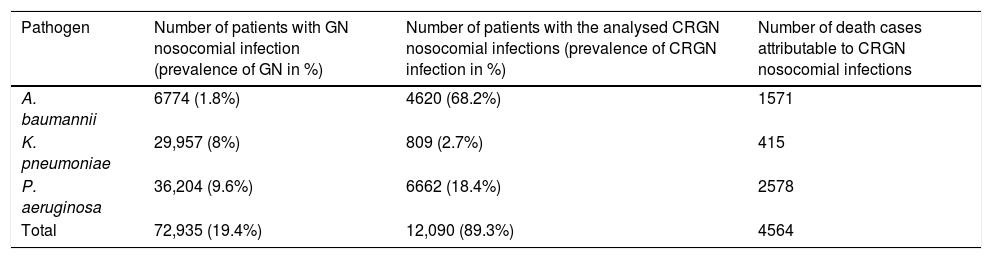

ResultsClinical impactA total of 4,862,352 hospital discharges were registered by INE during the year 2017 in Spain. It was estimated that 376,346 patients could have suffered a nosocomial infection over this period, which 9.6% were produced by P. aeruginosa, 8% by K. pneumoniae and 1.8% by A. baumannii. Patients with GN nosocomial infections by P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii represent 19.4% of the total number of patients with GN nosocomial infections in Spain. Approximately 12,090 patients (3.2% of the total number of patients who could have suffered a nosocomial infection) would have had a CRGN nosocomial infection produced by the three pathogens of study, being A. baumannii the most prevalent as shown in Table 1.

Prevalence of Gram-negative (GN) and carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative (CRGN) infections and mortality caused by A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa in Spain in 2017.

| Pathogen | Number of patients with GN nosocomial infection (prevalence of GN in %) | Number of patients with the analysed CRGN nosocomial infections (prevalence of CRGN infection in %) | Number of death cases attributable to CRGN nosocomial infections |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. baumannii | 6774 (1.8%) | 4620 (68.2%) | 1571 |

| K. pneumoniae | 29,957 (8%) | 809 (2.7%) | 415 |

| P. aeruginosa | 36,204 (9.6%) | 6662 (18.4%) | 2578 |

| Total | 72,935 (19.4%) | 12,090 (89.3%) | 4564 |

Mortality represented 37.8% of the total number of patients who would have had a CRGN nosocomial infection produced by the three pathogens of study. Of the analysed CRGN pathogens, P. aeruginosa produced the highest mortality (57%), followed by A. baumannii (34%), and K. pneumoniae (9%).

From the supplementary appendix of Cassini et al. (2019), it was obtained that CRGN nosocomial infections produced a total of 13,353 DALYs.16P. aeruginosa infections accounted for the healthiest life years lost (80%). K. pneumonaie caused 10%, and A. baumannii 10%.

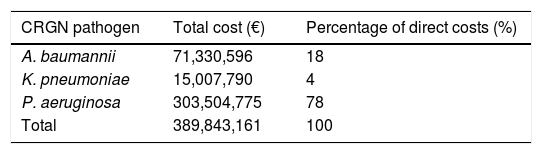

Economic impactDirect costsDirect costs of CRGN nosocomial infections were estimated to be 390M€ based on costs of hospitalisation episode according to each type of CRGN pathogen. As it is shown in Table 2, P. aeruginosa was the pathogen that caused the highest direct costs (78%), followed by A. baumannii (18%) and K. pneumoniae (4%).

Total direct costs of CRGN infections in 2017 obtained from incremental costs of hospitalisation episode according to the type of CRGN pathogen.

| CRGN pathogen | Total cost (€) | Percentage of direct costs (%) |

|---|---|---|

| A. baumannii | 71,330,596 | 18 |

| K. pneumoniae | 15,007,790 | 4 |

| P. aeruginosa | 303,504,775 | 78 |

| Total | 389,843,161 | 100 |

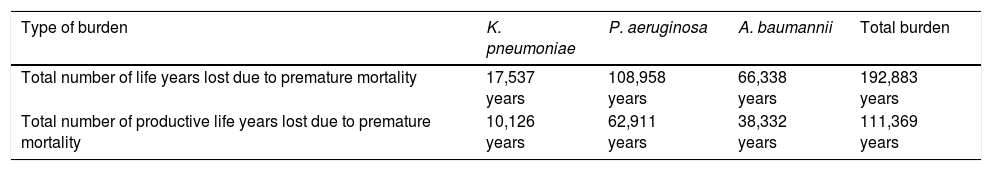

Table 3 shows the total number of years of life lost and productive years of life lost due to premature mortality.

Total number of life years and total number of productive life years lost due to premature mortality of CRGN nosocomial infections by type of GN pathogen.

| Type of burden | K. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | A. baumannii | Total burden |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of life years lost due to premature mortality | 17,537 years | 108,958 years | 66,338 years | 192,883 years |

| Total number of productive life years lost due to premature mortality | 10,126 years | 62,911 years | 38,332 years | 111,369 years |

It was estimated that 192,833 years of life were lost due to premature mortality produced by CRGN nosocomial infections. Infections caused by P. aeruginosa were the ones that produced the highest number of years of life lost (57%), followed by A. baumannii (34%). Loss of productive years of life due to premature mortality caused by CRGN nosocomial infections were estimated to be 111,369 years, with P. aeruginosa infections being the ones that produce the highest number of working life lost (57%).

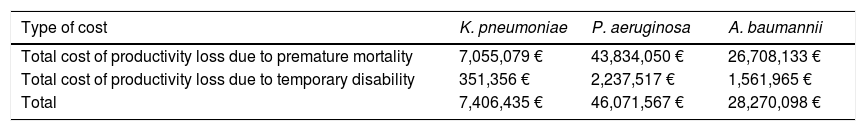

Table 4 shows the total indirect costs produced by premature mortality and temporary disability.

Indirect costs of CRGN nosocomial infections by type of GN pathogen.

| Type of cost | K. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | A. baumannii |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost of productivity loss due to premature mortality | 7,055,079 € | 43,834,050 € | 26,708,133 € |

| Total cost of productivity loss due to temporary disability | 351,356 € | 2,237,517 € | 1,561,965 € |

| Total | 7,406,435 € | 46,071,567 € | 28,270,098 € |

The economic impact of productivity loss due to premature mortality was estimated to be 78M€. P. aeruginosa generated 57% of the total, followed by A. baumannii (34%) and K. pneumoniae (9%). In addition, it was estimated that the economic impact of productivity loss due to temporary disability was 4M€: 54% generated by P. aeruginosa and 37% produced by A. baumannii. K. pneumoniae was the pathogen that produced the lowest loss (9%).

Total indirect costs obtained from the sum of productivity loss due to premature mortality and temporary disability generated a total of 82M€. Infections caused by CR P. aeruginosa were the ones that produced the highest indirect costs, 46M€ (56%), while infections caused by CR K. pneumoniae were the ones which produced the lowest indirect costs, 7M€ (9%).

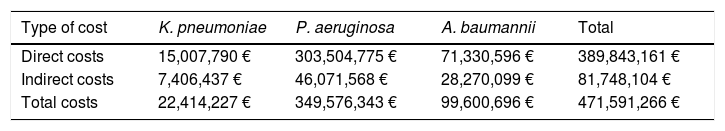

Total costsTotal economic costs caused by CRGN infections were estimated to be 472M€ as shown in Table 5. Direct costs represented 83% of total economic costs and indirect costs, 17%. Infections by P. aeruginosa had the highest estimated total cost, 350M€ (74%).

Total costs of CRGN infections by type of GN pathogen.

| Type of cost | K. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | A. baumannii | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct costs | 15,007,790 € | 303,504,775 € | 71,330,596 € | 389,843,161 € |

| Indirect costs | 7,406,437 € | 46,071,568 € | 28,270,099 € | 81,748,104 € |

| Total costs | 22,414,227 € | 349,576,343 € | 99,600,696 € | 471,591,266 € |

This study shows the projected clinical and economic burden of nosocomial infections produced by CRGN pathogens in Spain for the year 2017.

It was estimated that 376,346 patients could have suffered a nosocomial infection in Spain in 2017 and 12,090 of them would have had a CRGN nosocomial infection produced by the three pathogens of study. P. aeruginosa produced the highest mortality, resulting in 2587 deaths. Total economic costs of CRGN nosocomial diseases were estimated to be 472M€ in 2017. Direct costs accounted for 390M€ (83%) and indirect costs represented 82M€ (17%). P. aeruginosa was the pathogen that caused the highest direct costs.

To our knowledge, there are few research studies regarding the burden of CRGN nosocomial infections worldwide and in Spain. On a global level, several research studies concerning the developing of CR in GN pathogens were conducted, such as these by Meletis (2016) and Codjoe et al. (2017), which marked it as an ongoing threat to public health.11,22 Authors such as Giske et al. (2008) and Koulenti et al. (2019) studied hospital-acquired infections due to GN pathogens, but they did not specifically cover the CR pathogens.23,24 Notably, Giske et al. (2008) used a similar approach to this study, as they emphasised the challenge posed by the substantial clinical and economic impact that MDR GN pathogens have on society. However, they only considered hospital costs for the economic impact, not taking mortality into consideration.23 Britt et al. (2018) researched CRGN pathogens, but they centred their study on the clinical impact that sepsis caused by these pathogens has on hospitalised patients in the US.25 Moreover, Maltezou et al. (2013) studied CRGN nosocomial infections in hospitalised children in Greece, concluding that these infections are associated with significant morbidity and mortality.26

Some research about the clinical and economic implications of general nosocomial infections has also been carried out both in Spain and Europe. It was estimated that nosocomial infections produced 37,000 annual deaths and 7 billion euros in direct costs in Europe during 2016 and 2017.27 In Spain, nosocomial infections are ranked fourth in potential years of life lost in 2019, behind ischaemic heart disease, lung cancer and Alzheimer's disease. Moreover, they are estimated to cause more than 13,000 deaths and cost more than 600 million euros per year.28

It should be highlighted, notwithstanding, that there are several differences between the prevalence of CRGN pathogens in Spain and the rest of Europe:13 the prevalence of A. baumannii in Spain is higher than the average prevalence in Europe by a significant margin (68.2% and 33.4%, respectively). P.aeruginosa's prevalence is also higher in Spain (18.4%) than in Europe (17.4%). On the contrary, K.pneumoniae's prevalence is lower (2.7% in Spain and 7.2% in Europe). Therefore, infections produced by these pathogens do not have the same impact in Spain than in the rest of EU.

There are some limitations to our study that need to be discussed and could be solved in future prospective research. Our results could slightly underestimate or overestimate the prevalence of nosocomial infections and potential mortality, since it has been supposed that the distribution of the prevalence of nosocomial infections in Spain is homogeneous between hospitals. Moreover, the prevalence percentage of CRGN pathogens has been assumed to be the same for every public health system hospital, given that it was based in a representative sample of hospitals included in the Atlas of Infectious Diseases. The total number of years of life lost and productive years of life lost due to premature mortality could have been overestimated because the Spanish population distributed by age was assumed proportional to the number of CRGN nosocomial infections.

In addition, this study might underestimate the total costs of CRGN infections in Spain. First, we only included the costs of the hospitalisation episode into the direct costs, not the costs of the whole process of CRGN infections which are higher. Second, the direct costs were obtained from Riu et al. for 2012 and therefore, they do not include the costs of antibiotics approved afterwards which are more expensive.17 Third, indirect costs, specifically productivity loss due to temporary disability, may be underestimated since a hospital discharge does not mean an immediate work discharge. Fourth, data on fatality cases or hospital length of stay due to CRGN infections are not publicly available. The proportion of fatality cases and the length of stay were obtained from Cassini et al. (2019)6 because information was presented by type of CRGN pathogen. This information was consistent with the last report published by the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC) that estimated 30-day mortality due to MDR in 82 Spanish hospitals in 9204 fatality cases in 2018, being CR P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae one of the most frequent pathogens.1

More burden of disease studies should be conducted to gain a more valuable approach to this major health problem. It would also be interesting to analyse the link between DALYs and mortality over time in order to understand whether a better quality of life is reached in patients with CRGN nosocomial infections when a certain survival rate is obtained.

Considering that the risks CRGN infections are currently posing to public health will increase in a near future, this study might help create awareness about this problem amongst the general population and health professionals.

Conflict of interestsRC and LM have conflict of interest: RC has participate in educational programs sponsored by MSD, Pfizer and Shionogi; LM has participated in educational programs sponsored by MSD, Pfizer and Angelini. RM and JG are employees of Shionogi. The rest of authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This study has been performed with a research grant from Shinogi.