Due to hepatitis B virus (HBV) treatment and vaccination during the last decades in Spain, epidemiological and prognosis of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) may have changed.

MethodsRetrospective review of CHB-HIV coinfected patients in a single reference center in Madrid until year 2019. We compared incidence, epidemiological and clinical characteristics according diagnosis period (before 2000, 2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2010–2014, 2015–2019). A retrospective longitudinal study was done to assess mortality, related risk factors and hepatic decompensation.

ResultsOut of 5452 PLHIV, 160 had CHB (prevalence 2.92%; 95%CI 2.5–3.4), 85.6% were men, median age 32.1 (27−37.2). Incidence rate did not change over the years (2.4/100 patients-year). PLHIV with CHB diagnosed before year 2000 (n = 87) compared with those diagnosed between 2015 and 2019 (n = 11) were more often native-Spanish (90.8% vs. 18.2%), had infected using intravenous drugs (55.2% vs. 0), were coinfected with hepatitis C (40% vs. 9.1%) or hepatitis delta virus (30.4% vs. 0) and had more severe liver disease (cirrhosis 24.1% vs. 0). After a median follow-up of 20.4 years, 23 patients died (7.1/1000 patients-year) and 19 had liver decompensation (4.9/1000 patients-year). All deaths and liver decompensation occurred in patients diagnosed before year 2010. Mortality was associated with higher liver fibrosis in Fibroscan® (HR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03−1.09).

ConclusionThe epidemiology of CHB in PLHIV in our cohort is changing with less native Spanish, more sexually transmitted cases and less coinfection with other hepatotropic virus. Patients diagnosed before 2010 have worst prognosis related to higher grades of liver fibrosis.

La vacunación, los avances en el tratamiento frente al virus de la hepatitis B (VHB) y los cambios epidemiológicos producidos en España en las últimas décadas han podido modificar las características y el pronóstico de la hepatitis crónica B (HCB) en personas que viven con VIH (PVIH).

MétodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo donde se incluyeron PVIH-HCB en seguimiento en una unidad de referencia madrileña hasta el año 2019. Se comparó la incidencia y las características epidemiológicas y clínicas según el momento del diagnóstico (antes del año 2000 y posteriormente en periodos de 5 años). Además, se realizó un estudio longitudinal retrospectivo evaluando la tasa de mortalidad, descompensación hepática y factores asociados.

ResultadosDe 5452 PVIH, 160 presentaban HCB en el momento basal (prevalencia 2,92%,IC95%:2,5−3,4), 85,6% hombres, edad mediana al diagnóstico, 1(27–37,2) años. La incidencia (2,4/100 pacientes-año) no varió en los diferentes periodos. Los pacientes diagnosticados antes del 2000 (n = 87) comparados con los diagnosticados entre 2015–2019 (n = 11) con mayor frecuencia eran nativos españoles (90,8% vs. 18,2%), habían consumido drogas intravenosas (55,2% vs. 0), tenían antecedentes de hepatitis C (40% vs. 9,1%) y delta (30,4% vs. 0) y mayor afectación hepática (24,1% cirróticos vs. 0). Tras un seguimiento de 20,4 años, 23 pacientes murieron (7,1/1000 pacientes-año) y 19 presentaron descompensación hepática (4,9/1000 pacientes-año), todos diagnosticados antes del año 2010. La mortalidad se asoció con mayor fibrosis hepática basal estimada por Fibroscan® (HR 1,06; IC95%:1,03-1,09).

ConclusiónLas PVIH-HCB con diagnóstico previo al año 2000 son más frecuentemente de nacionalidad española, infectadas por vía parenteral y con mayor prevalencia de otras coinfecciones. Los pacientes diagnosticados antes del 2010 tienen peor pronóstico condicionado por presentar mayor grado de fibrosis hepática.

Almost 37 million people worldwide are infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), of which between 5% and 10% also have chronic hepatitis B (CHB).1 The prevalence of coinfection among people living with HIV (PLHIV) varies geographically, and is higher in sub-Saharan Africa or Asia. In Western Europe, the prevalence is around 5%. Different studies have shown higher prevalence of coinfection in intravenous drug users (IDUs) and men who have sex with men (MSM).2,3

There are several factors that have modified the prevalence of coinfection by HIV and the hepatitis B virus (HBV) in the last decade in Spain. In the first place, in Spain, the recommendation to start vaccination against HBV began in people at risk (including PLHIV) in 1982, and was rolled out to the rest of the population until newborns were included in 2002.3 Furthermore, the epidemiology of HIV infection has changed significantly. While more than 50% of PLHIV were IDUs prior to the year 2000, in the first decade of the 21st century IDUs did not exceed one-third of new HIV diagnoses. Moreover, there has been an increase in the immigrant population from countries with higher rates of CHB and lower vaccination rates.4

The introduction of tenofovir as part of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has led to better control of HBV in coinfected patients, with less progression to cirrhosis and less morbidity and mortality. However, the studies carried out to date show discrepancies both in response rates to HBV treatment and in morbidity and mortality.5–8 These differences may be due to variations in the underlying mortality rates in the cohorts studied, and to differences in treatment strategies and the management of both HIV infection and CHB.

The objectives of our study were twofold. First, to evaluate the changes over the years in the epidemiological characteristics and degree of liver fibrosis in coinfected patients at our centre. Second, to evaluate the mortality, rate of hepatic decompensation and response to treatment after the introduction of tenofovir.

MethodsThe study is a retrospective study that included all patients coinfected with HBV at the time of inclusion in our cohort. CHB was defined as positive HBsAg for at least six months.

For the first objective, in order to evaluate the changes in the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of PLHIV with CHB over the years, a retrospective longitudinal study was carried out comparing incidence, and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at the baseline moment of inclusion in our cohort, in different periods since the beginning of the HIV epidemic: before the year 2000, from 2000 to 2004, from 2005 to 2009, from 2010 to 2014 and from 2015 to 2019. Sociodemographic variables (age, gender, origin and risk factor for contracting HIV) and clinical variables (coinfection with hepatitis C [HCV] or D [HDV]) were collected. The first estimate made of liver fibrosis measured by transient elastography (FibroScan® [FS]) was collected. A liver elasticity value >12 kPa was considered advanced fibrosis.9

For the second objective, we analysed the mortality rate, the appearance of hepatic decompensation and HBV microbiological parameters such as the presence of an HBV viral load (HBV-DNA) less than 20 units/mL at the end of follow-up, a negative e-antigen (HBeAg) test result and s-antigen (HBsAg) clearance.

Statistical analysisThe qualitative variables were presented as absolute number and percentage with respect to the total, and the quantitative variables with the median and the interquartile range (IR = P25-P75). Comparisons between qualitative variables were made using the χ2 statistical tests (linear association). Quantitative variables were compared with the Wilcoxon non-parametric test.

A univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis was performed to determine the variables associated with having a higher degree of fibrosis on FS.

For the longitudinal analysis, each patient was followed up until death, decompensation, HBeAg or HBsAg negative test results, or until their last visit at our centre. The incidence was calculated in cases per 1,000 patient-years. The data were censored in December 2020. The incidence of each event was calculated per 1,000 patient-years. Finally, a univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to determine the factors associated with mortality.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario La Paz [La Paz University Hospital] in January 2022 (Approval Code PI-5065), following the current legislation for observational studies with medicinal products (Royal Decree 1090/2015). All data were included in an anonymised database. Due to its retrospective characteristics and the fact that the data collected were not identifiable, the local committee waived the need for informed consent. All the research was carried out in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data, and the Declaration of Helsinki.

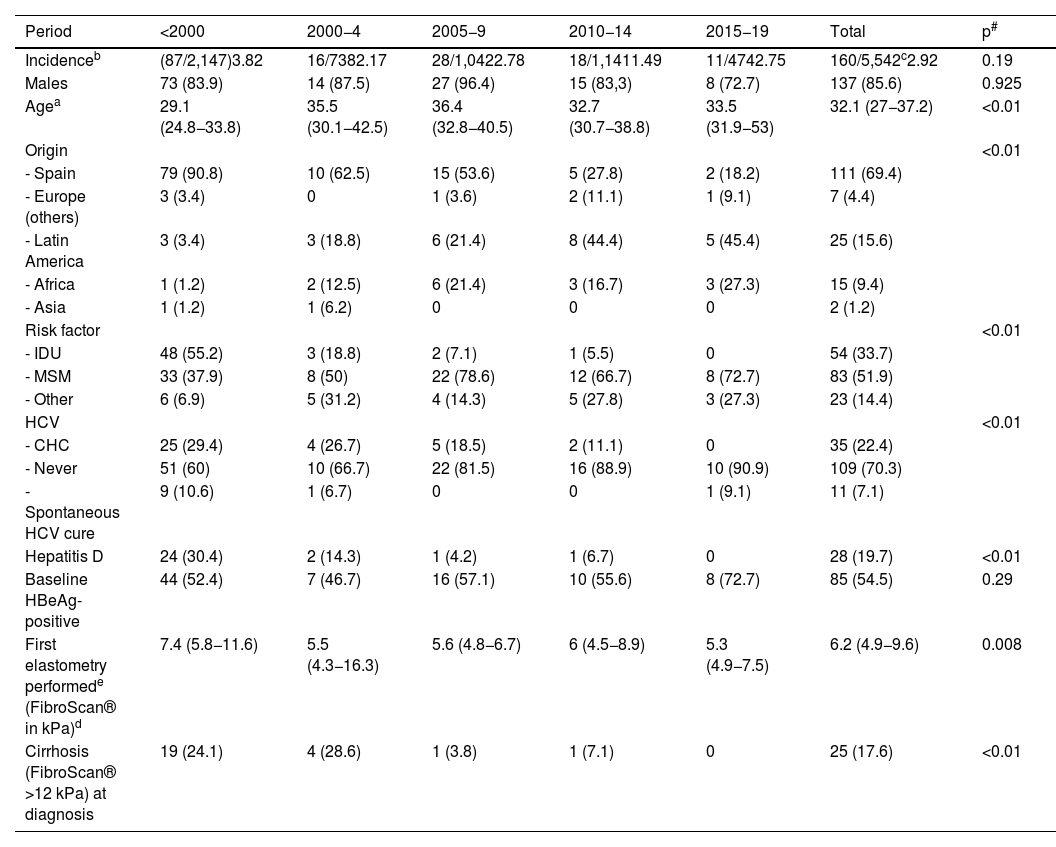

ResultsComparison of baseline characteristics over the yearsOf the 5,542 patients followed up at the HIV specialist clinic, 160 also had CHB at the time of entering our cohort (prevalence 2.92%, 95% CI: 2.5–3.4). The incidence did not vary in the different periods (Table 1). The median age of the patients at diagnosis was 32.1 (27−37.2) years and the majority were male. In the last period (from 2015 to 2020), the patients diagnosed with CHB were older (33.5 years in the last period vs. 29.1 years if the diagnosis was before 2000), immigrants (more than half of the diagnoses were in people from Latin America) and through sexual transmission (especially MSM). Coinfection with other hepatotropic viruses decreased over the periods: 40% and 30.4% of patients infected before 2000 had or had had hepatitis C and D, respectively, while, from 2015, only one case of HCV coinfection was observed. Finally, patients diagnosed before 2000 had greater liver involvement, with advanced fibrosis observed in almost a quarter of them (Table 1).

Patient characteristics by year of diagnosis.

| Period | <2000 | 2000−4 | 2005−9 | 2010−14 | 2015−19 | Total | p# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidenceb | (87/2,147)3.82 | 16/7382.17 | 28/1,0422.78 | 18/1,1411.49 | 11/4742.75 | 160/5,542c2.92 | 0.19 |

| Males | 73 (83.9) | 14 (87.5) | 27 (96.4) | 15 (83,3) | 8 (72.7) | 137 (85.6) | 0.925 |

| Agea | 29.1 (24.8−33.8) | 35.5 (30.1−42.5) | 36.4 (32.8−40.5) | 32.7 (30.7−38.8) | 33.5 (31.9−53) | 32.1 (27−37.2) | <0.01 |

| Origin | <0.01 | ||||||

| - Spain | 79 (90.8) | 10 (62.5) | 15 (53.6) | 5 (27.8) | 2 (18.2) | 111 (69.4) | |

| - Europe (others) | 3 (3.4) | 0 | 1 (3.6) | 2 (11.1) | 1 (9.1) | 7 (4.4) | |

| - Latin America | 3 (3.4) | 3 (18.8) | 6 (21.4) | 8 (44.4) | 5 (45.4) | 25 (15.6) | |

| - Africa | 1 (1.2) | 2 (12.5) | 6 (21.4) | 3 (16.7) | 3 (27.3) | 15 (9.4) | |

| - Asia | 1 (1.2) | 1 (6.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.2) | |

| Risk factor | <0.01 | ||||||

| - IDU | 48 (55.2) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (7.1) | 1 (5.5) | 0 | 54 (33.7) | |

| - MSM | 33 (37.9) | 8 (50) | 22 (78.6) | 12 (66.7) | 8 (72.7) | 83 (51.9) | |

| - Other | 6 (6.9) | 5 (31.2) | 4 (14.3) | 5 (27.8) | 3 (27.3) | 23 (14.4) | |

| HCV | <0.01 | ||||||

| - CHC | 25 (29.4) | 4 (26.7) | 5 (18.5) | 2 (11.1) | 0 | 35 (22.4) | |

| - Never | 51 (60) | 10 (66.7) | 22 (81.5) | 16 (88.9) | 10 (90.9) | 109 (70.3) | |

| - Spontaneous HCV cure | 9 (10.6) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 11 (7.1) | |

| Hepatitis D | 24 (30.4) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 28 (19.7) | <0.01 |

| Baseline HBeAg-positive | 44 (52.4) | 7 (46.7) | 16 (57.1) | 10 (55.6) | 8 (72.7) | 85 (54.5) | 0.29 |

| First elastometry performede (FibroScan® in kPa)d | 7.4 (5.8−11.6) | 5.5 (4.3−16.3) | 5.6 (4.8−6.7) | 6 (4.5−8.9) | 5.3 (4.9−7.5) | 6.2 (4.9−9.6) | 0.008 |

| Cirrhosis (FibroScan® >12 kPa) at diagnosis | 19 (24.1) | 4 (28.6) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 25 (17.6) | <0.01 |

CHC, chronic hepatitis C at any time; IDU, intravenous drug use; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MSM, men who have sex with men.

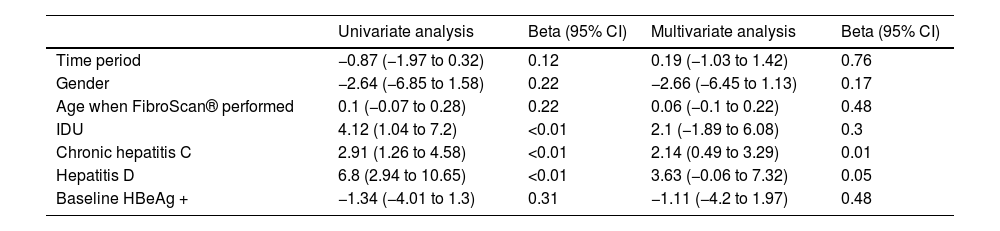

A median of 10.3 years (1.42–16.87) elapsed from the diagnosis of HIV infection until the first FS was performed. The median value of the FS was 6.2 kPa (4.9−9.6); 25 patients (17.6%) had advanced fibrosis. The only factor associated with greater fibrosis was HCV coinfection. The incidence of fibrosis was greater in patients coinfected with HDV, but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.05) (Table 2).

Factors associated with greater fibrosis on FibroScan®.

| Univariate analysis | Beta (95% CI) | Multivariate analysis | Beta (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time period | −0.87 (−1.97 to 0.32) | 0.12 | 0.19 (−1.03 to 1.42) | 0.76 |

| Gender | −2.64 (−6.85 to 1.58) | 0.22 | −2.66 (−6.45 to 1.13) | 0.17 |

| Age when FibroScan® performed | 0.1 (−0.07 to 0.28) | 0.22 | 0.06 (−0.1 to 0.22) | 0.48 |

| IDU | 4.12 (1.04 to 7.2) | <0.01 | 2.1 (−1.89 to 6.08) | 0.3 |

| Chronic hepatitis C | 2.91 (1.26 to 4.58) | <0.01 | 2.14 (0.49 to 3.29) | 0.01 |

| Hepatitis D | 6.8 (2.94 to 10.65) | <0.01 | 3.63 (−0.06 to 7.32) | 0.05 |

| Baseline HBeAg + | −1.34 (−4.01 to 1.3) | 0.31 | −1.11 (−4.2 to 1.97) | 0.48 |

Beta, change in one FibroScan® unit for each factor.

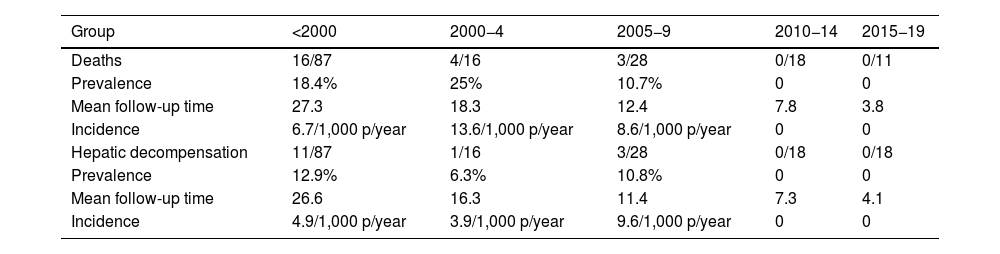

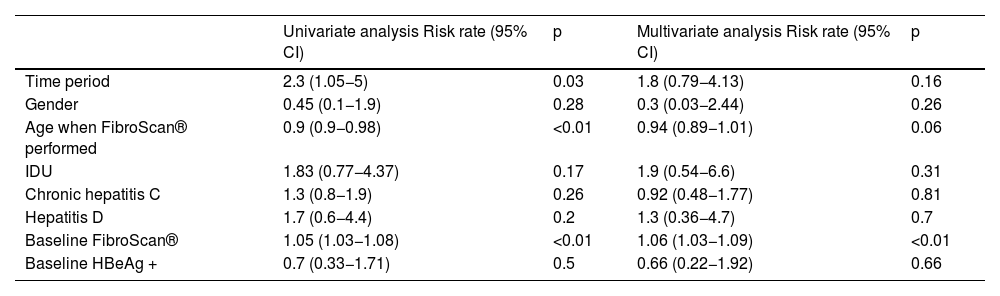

The median follow-up time was 20.4 years (IQR 11–28.2). During this period, 23 patients died (mortality rate: 7.1 per 1,000 patient-years). In nine cases the cause was hepatic, while six were due to hepatocellular carcinoma. Higher mortality was observed in the first three study periods, with no deaths observed in patients diagnosed after 2010 (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, a higher degree of baseline fibrosis (measured by FS) was associated with higher mortality (Table 4).

Mortality and hepatic decompensation between time periods.

| Group | <2000 | 2000−4 | 2005−9 | 2010−14 | 2015−19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths | 16/87 | 4/16 | 3/28 | 0/18 | 0/11 |

| Prevalence | 18.4% | 25% | 10.7% | 0 | 0 |

| Mean follow-up time | 27.3 | 18.3 | 12.4 | 7.8 | 3.8 |

| Incidence | 6.7/1,000 p/year | 13.6/1,000 p/year | 8.6/1,000 p/year | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatic decompensation | 11/87 | 1/16 | 3/28 | 0/18 | 0/18 |

| Prevalence | 12.9% | 6.3% | 10.8% | 0 | 0 |

| Mean follow-up time | 26.6 | 16.3 | 11.4 | 7.3 | 4.1 |

| Incidence | 4.9/1,000 p/year | 3.9/1,000 p/year | 9.6/1,000 p/year | 0 | 0 |

Factors associated with mortality in patients with chronic hepatitis B (Cox regression).

| Univariate analysis Risk rate (95% CI) | p | Multivariate analysis Risk rate (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time period | 2.3 (1.05−5) | 0.03 | 1.8 (0.79−4.13) | 0.16 |

| Gender | 0.45 (0.1−1.9) | 0.28 | 0.3 (0.03−2.44) | 0.26 |

| Age when FibroScan® performed | 0.9 (0.9−0.98) | <0.01 | 0.94 (0.89−1.01) | 0.06 |

| IDU | 1.83 (0.77−4.37) | 0.17 | 1.9 (0.54−6.6) | 0.31 |

| Chronic hepatitis C | 1.3 (0.8−1.9) | 0.26 | 0.92 (0.48−1.77) | 0.81 |

| Hepatitis D | 1.7 (0.6−4.4) | 0.2 | 1.3 (0.36−4.7) | 0.7 |

| Baseline FibroScan® | 1.05 (1.03−1.08) | <0.01 | 1.06 (1.03−1.09) | <0.01 |

| Baseline HBeAg + | 0.7 (0.33−1.71) | 0.5 | 0.66 (0.22−1.92) | 0.66 |

IDU, intravenous drug user.

In total, 19 patients had hepatic decompensation (incidence rate 4.9 per 1,000 patient-years). All cases of decompensation occurred in patients diagnosed before 2010.

Regarding the response to HBV treatment, all patients began treatment with tenofovir at some point during their follow-up (always in combination with emtricitabine). Median time elapsed from diagnosis to treatment was 9.7 years (0.7–15.5). At the end of follow-up, 135 out of 153 (88.2%) had HBV-DNA <20 copies/mL, 31 out of the 87 baseline HBeAg-positive patients had become HBeAg-negative (48.1 per 1,000 patient-years) and 13 out of 159 patients had become HBsAg-negative (8.2 per 1,000 patient-years). Median follow-up times for HBeAg and HBsAg negativisation were 7.4 and 9.8 years, respectively.

DiscussionThe first observation of our study is that the epidemiological characteristics of PLHIV with CHB have been changing since the beginning of the HIV epidemic. We have gone from a profile of patients who are IDUs, Spanish natives and coinfected with other hepatotropic viruses, to patients who are infected by sexual transmission, immigrants and without other chronic hepatitis infections. In Spain, vaccination against HBV in risk groups began in 1982, and since 2002 it has been universal, causing a decrease in incidence over the years in Spanish natives.3 However, the global incidence of CHB in PLHIV has not decreased due to an increase in PLHIV coming from countries with a higher incidence of CHB without universal vaccination programmes.10 Our group recently reported a decrease in the incidence of acute hepatitis B (AHB) in PLHIV. The few diagnoses there were occurred in young MSM from Latin American countries.11 It is important to be aware of these data in order to organise prevention and management strategies in these population groups.

With the improvement in antiretroviral therapy and, specifically, with the introduction of tenofovir in the early 21st century, there has been a significant decrease in morbidity and mortality in patients coinfected with HIV and HBV.12 In our study, patients diagnosed after 2010 had a lower degree of fibrosis and no deaths or cases of hepatic decompensation were recorded. In addition, patients diagnosed in the early stages had higher rates of HCV or HDV coinfection, which was associated with higher rates of fibrosis. In the survival study, the degree of fibrosis measured by FS was the only factor that was independently related to higher mortality.

Since the introduction of tenofovir and after a mean follow-up of almost 10 years, about 90% of our patients had undetectable HBV-DNA, 35.6% became HBeAg-negative and 8.2% achieved a functional cure (HBsAg clearance). These results are similar to those described by Dezanet et al.,13 although some studies have described higher rates of functional cure, between 10% and 15%,14,15 also higher than the 1% per year reported in mono-infected patients.16 Chicota et al. found an association between HBsAg clearance and a lower CD4+ count, relating to a phenomenon of immune reconstitution.14 The lower functional cure rate in our study may be due to multiple factors. In the first place, it is a retrospective study without regulated performance of the HBsAg measurement, so the clearance of sAg may be underestimated. In addition, it is a different population, not always naïve and possibly with better immunity, which would reduce the phenomena of immune reconstitution. Despite this, it is important to stress the importance of regular check-ups to rule out seroreversion, which leads to lower mortality and lower risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.17 On the other hand, PLHIV might currently want to benefit from combination therapies with drugs that have no effect against HBV.18 In all the cohorts of coinfected patients, the suppression rates of the HBV viral load with tenofovir are high (in our case above 90%).

Our study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective observational study of routine clinical practice. While measuring HBV viral load is a constant practice in our routine practice, the determination of other markers (HBsAg and HBeAg) is not so constant. Therefore, clearance data for these antigens may be underestimated. Secondly, in our study we included the patients registered in our electronic database, which began to be generated from the year 2000. Therefore, patients diagnosed before then, but still active in 2000, were included. However, patients lost or previously deceased could not be included, so it is to be expected that mortality is even higher in the first study group. Moreover, in patients diagnosed after 2010, the follow-up is too short to assess mortality. A median of 10 years elapsed between diagnosis and the FS test. It would have been more appropriate for all patients to undergo this test at diagnosis, but it was not available at our centre as routine clinical practice until after 2005. Finally, we must highlight that, although some patients from other Spanish regions are being followed up at the specialist clinic, most of the patients are residents of the Community of Madrid, so the results may not be completely extrapolatable to Spain as a whole.

In conclusion, the characteristics of PLHIV coinfected with HBV in Spain are changing. Patients diagnosed before 2010 have a worse prognosis in terms of mortality and hepatic decompensation, which is mainly due to having a higher degree of fibrosis. In patients with HBV control, fibrosis is mainly associated with a previous history of other viral liver diseases.

FundingThis study has not received any type of funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this study.

We would like to thank all healthcare professionals for their outstanding efforts and dedication to patient care. We would like to dedicate this article to our patients who have suffered from the disease and their families.