A 54-year-old man with a history of hereditary haemochromatosis and hypertensive heart disease, referred to Dermatology for assessment of an asymptomatic skin lesion on the left forearm without associated extracutaneous symptoms (Fig. 1).

The patient reported the appearance, three months earlier, of two small papulous lesions that had slowly increased in size. He had not travelled recently, denied contact with animals, plants or aquariums and did not remember any injury to the area.

He had received topical and oral antibiotic treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (875/125) for 10 days without improvement. The physical examination found a round, purplish plaque on the left forearm measuring 6 cm in diameter, with an erosive surface and bloody crusts. Nearby, but not distributed along the lymphatic vessels, were two smooth satellite lesions measuring 1 cm and 2 cm in diameter. No regional lymphadenopathies could be palpated. A punch biopsy of the main lesion was performed for histology and microbiology studies.

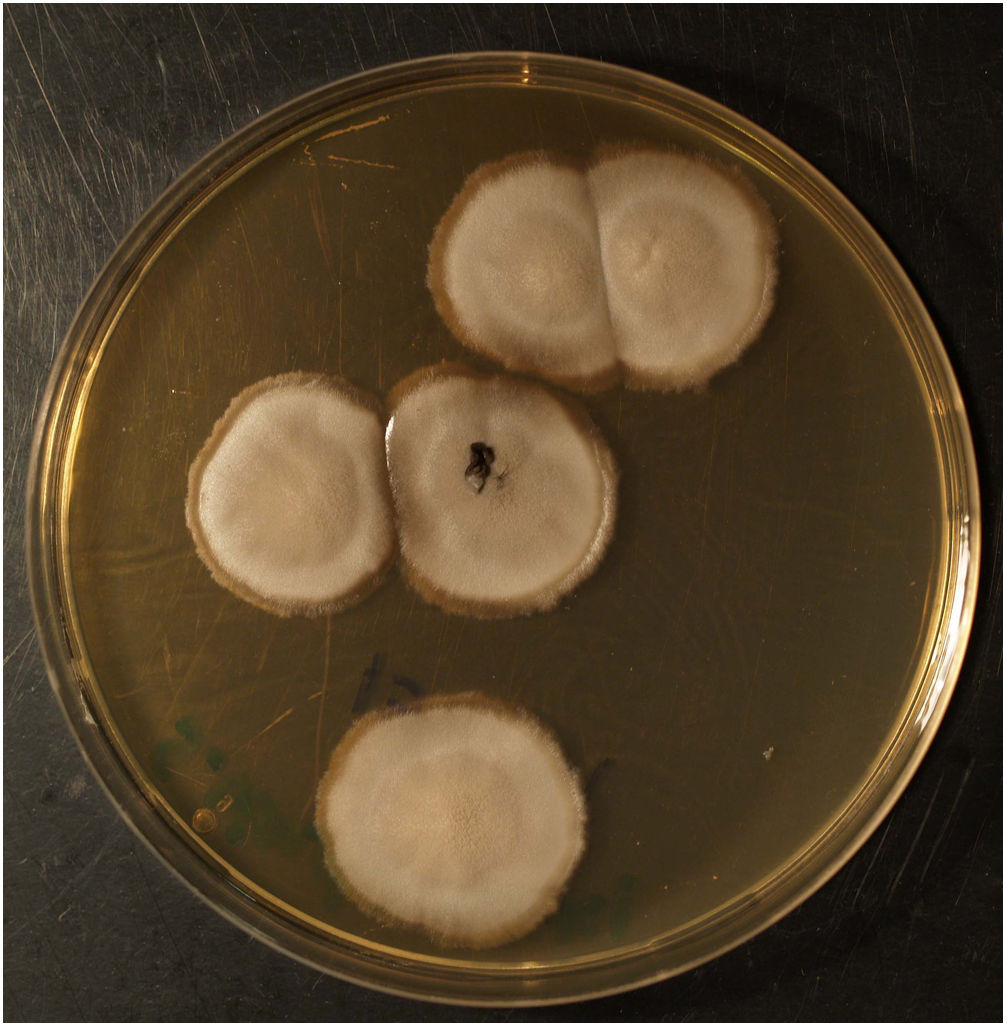

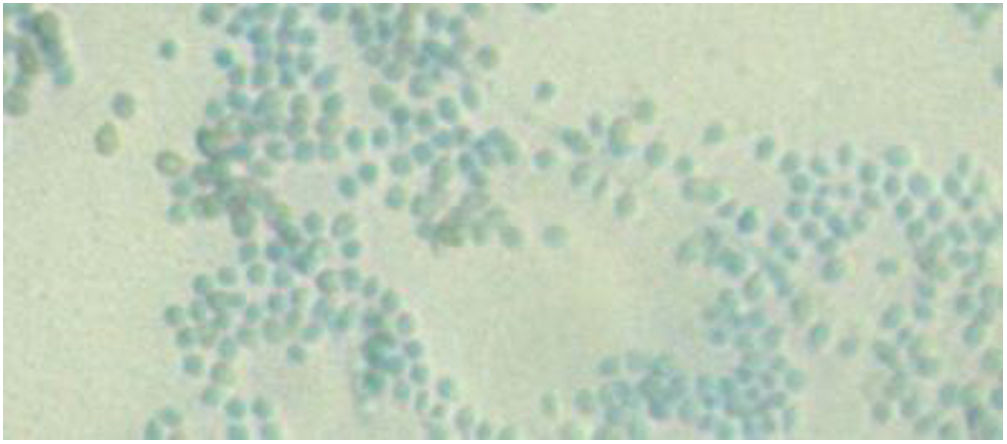

Clinical courseThe histology study observed abscessified granulomas in the dermis and underlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. PAS, Grocott, Giemsa and Ziehl-Neelsen stains were negative. In Sabouraud medium with gentamicin and chloramphenicol at 30 °C, growth was observed in the biopsy material of a filamentous fungus with morphology and microscopy examination compatible with the identification of Sporothrix schenckii complex (Figs. 2 and 3). Definitive identification was carried out by ITS region sequencing and MALDI-TOF MS (VITEK® MS, bioMérieux).

With the diagnosis of fixed cutaneous sporotrichosis, the treatment undertaken was itraconazole 200 mg/day for five months, with good tolerance and healing of the lesion. The patient, a plasterer by occupation, reported working on the restoration of an old house that had been uninhabited for a long period.

Closing remarksSporotrichosis is a subacute or chronic granulomatous subcutaneous fungal infection caused by the dimorphic fungus S. schenckii complex, which includes six species with differences in geographic distribution, biochemical characteristics, degree of virulence, patterns of disease and response to treatments (S. albicans, S. brasiliensis, S. luriei, S. globosa, S. mexicana and S. schenckii sensu stricto).1 Sporotrichosis has worldwide distribution and is endemic in temperate and warm climates with high ambient humidity, but rarely described in Europe.2 In Spain, 53 cases were published between 1920 and 19993,4 and no increase in sporotrichosis has been detected in recent years,5 with isolated cases and one series of eight autochthonous patients in the province of Seville.6

S. schenckii is a saprophytic fungus found in soil and decomposing plants. The most common route of acquisition of the disease is by direct inoculation, observed most often in occupations relating to gardening, forestry, agriculture and carpentry, which would explain why most lesions are observed on the extremities, with the forearm being the most common location in adults. Skin traumas often go unreported.

The most common presentation of sporotrichosis is cutaneous, with fixed and lymphocutaneous variants. Its frequency varies according to the geographic area, with the fixed form presenting in 10–30% of cases versus 85% for the lymphocutaneous form.7

In lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, the point of inoculation appears as a nodular lesion, with new lesions appearing progressively with a linear distribution along the course of the lymphatic vessels. In the fixed cutaneous form, the lesions remain localised at the inoculation site. It is more common in children, in whom the facial location is predominant.1

The definitive diagnosis of cutaneous sporotrichosis is established by means of a fungal culture. The histopathological findings are nonspecific and do not enable it to be differentiated from other granulomatous diseases.

The treatment of choice for uncomplicated cutaneous forms is itraconazole at doses of 100–200 mg/day for three to six months. As second line treatment, terbinafine and fluconazole have been found to be effective. The treatment must be maintained for two to four weeks after the lesions have healed.

Sporotrichosis is a rare infection in our setting. Its heterogeneous clinical presentation can simulate other infectious granulomatous diseases or cutaneous tumours. Clinical suspicion of the lymphocutaneous form is more common than the fixed variety, which rarely considered in the diagnosis, especially in non-endemic areas. It is important to know the patient's occupational activity and to include sporotrichosis in the differential diagnosis of chronic skin lesions with a wide variety of clinical morphologies.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Yáñez Díaz S, Roiz Mesones MP. Placa erosiva y costrosa en antebrazo izquierdo. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:471–472.