The sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic techniques for Chagas disease depend largely on the antigens and targets used and on the immune response and characteristics of the infection of the population where it is applied, hence the need for evaluation of the diagnostic techniques available in a given area. So, the objective of this work was to evaluate two commercial kits for the immunological and molecular diagnosis of Chagas disease in endemic areas of Venezuela.

MethodsThe evaluated kits were: Chagas ELISA IgG+IgM® and Speed Oligo Chagas® (Vircell®, Granada, Spain). They were evaluated with 129 samples (35 from patients in the acute phase, 33 in the chronic phase, 31 from patients with other diseases, and 30 from healthy individuals). The results were compared with those obtained in the conventional ELISA and PCR-satellite DNA tests for Trypanosoma cruzi.

ResultsWith Chagas ELISA IgG+IgM® a sensitivity of 94.1% and specificity of 93.4% were obtained, with Speed Oligo Chagas® a sensitivity of 92.6% and specificity of 100% were achieved, values similar to those showed by conventional ELISA and satDNA-PCR.

ConclusionThe sensitivity and specificity of the commercial kits evaluated make them suitable for the diagnosis of Chagas disease in endemic areas of Venezuela.

La sensibilidad y especificidad de las técnicas de diagnóstico para la enfermedad de Chagas dependen en gran parte de los antígenos y las dianas utilizadas y de la respuesta inmunológica y las características de la infección de la población donde se aplica, de allí la necesidad de la evaluación de las técnicas de diagnóstico disponibles en un área determinada, por lo que el objetivo de este trabajo fue evaluar dos estuches comerciales para el diagnóstico inmunológico y molecular de la enfermedad de Chagas en zonas endémicas de Venezuela.

MétodosSe evaluaron los estuches: Chagas ELISA IgG+IgM® y Speed Oligo Chagas® (Vircell®, Granada, España). Se valoraron con 129 muestras (35 de pacientes en fase aguda, 33 en fase crónica, 31 de pacientes con otras enfermedades y 30 de individuos sanos). Se compararon los resultados con los obtenidos en las pruebas convencionales ELISA y PCR-ADN satélite de Trypanosoma cruzi.

ResultadosCon Chagas ELISA IgG+IgM® se obtuvo una sensibilidad de 94,1% y especificidad de 93,4%, con Speed Oligo Chagas® se obtuvo una sensibilidad de 92,6% y especificidad de 100%, valores similares a los obtenidos con ELISA y PCR-ADNsat convencionales.

ConclusiónLa sensibilidad y especificidad de los estuches comerciales evaluados los hacen adecuados para el diagnóstico de la enfermedad de Chagas en zonas endémicas de Venezuela.

Chagas disease is caused by the haemoflagellate Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi) and is transmitted to mammals by contact with faeces of infected triatomine bugs. The disease has an acute phase, with an abundance of parasites, followed by recovery or a chronic phase, with fewer parasites in circulation, which can present with no symptoms at all or with life-threatening cardiac, digestive and neurological symptoms. Between 6 and 7 million people currently have the disease and 25 million are at risk of infection1. In Venezuela, increased incidence and prevalence rates2–5, reports of acute cases6, increased number of blood samples testing positive for the disease in blood banks7 and outbreaks of orally transmitted disease8–10 have been described in recent years.

The disease is generally diagnosed using parasitological and immunological methods. The sensitivity of parasitological techniques may be low if the parasite burden is low. Although many of the techniques currently used to diagnose Chagas disease have high specificity, there may be some cross-reactivity to other related parasites and it is therefore very important to evaluate these techniques, especially in both Chagas disease and leishmaniasis-endemic areas. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique detects parasite-specific DNA sequences and is useful for diagnostic purposes. Although it has certain limitations, it is advantageous for acute cases, cases of congenital transmission, immunodeficiencies and therapy evaluation11,12.

There is consensus that the use of two techniques is recommended, with a third test advised if there is any discrepancy13. In Venezuela, the disease is commonly diagnosed at public and private healthcare centres using mainly commercial tests and the diagnosis is then generally confirmed by reference laboratories, although this can result in inconsistent results between the diagnoses reached at these centres and the reference laboratory results7.

Due to this problem, this study was designed to evaluate two commercial kits (ELISA and PCR, Vircell®, Granada, Spain) and to compare their diagnostic efficacy with our laboratory’s in-house ELISA and PCR tests (reference laboratory for the diagnosis of Chagas disease in the central region of Venezuela).

MethodsA total of 129 blood and serum samples were evaluated: 35 from patients in the acute phase, 33 from patients in the chronic phase, 31 from patients with other diseases (visceral leishmaniasis, n = 11; cutaneous leishmaniasis, n = 10; malaria, n = 5; and toxoplasmosis, n = 5) and 30 from healthy individuals. All samples were provided by two reference laboratories for the diagnosis of Chagas disease in the central region of Venezuela and were previously confirmed by clinical diagnosis, parasitological methods (stained blood smear, xenodiagnosis and blood culture) and immunodiagnostics using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), indirect haemagglutination assay and indirect immunofluorescence assay. The work protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of BIOMED-UC and all individuals had signed an informed consent form approving use of their samples for diagnostic and research purposes.

An in-house ELISA assay was performed using Maekelt’s T. cruzi antigen, as described,14 along with the commercial Chagas ELISA IgG+IgM® assay (Vircell®, Granada, Spain) according to the manufacturer’s instructions15.

DNA was extracted from the blood samples described above using Chelex® 100 resin (Bio-Rad, Hercules CA, USA) as described14. The PCR assay for the detection of T. cruzi satellite DNA16 was then performed using the primers TCZ1 (forward) 5′-CGAGCTCTTGCCCACACGGGTGCT-3′ and TCZ2 (reverse) 5′-CCTCCAAGCAGCGGATAGTTCAGG-3′. The amplification reaction products were analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis in accordance with the described protocols14. A PCR assay for the detection of T. cruzi satellite DNA and amplification of the product was also performed according to the protocol described by the Speed-oligo Chagas® manufacturer (Vircell®, Granada, Spain)15.

The results obtained with the in-house and commercial (Vircell®, Granada, Spain) ELISA and PCR assays were compared. The results were set out in contingency tables and the diagnostic indices of sensitivity and specificity were calculated along with correlation with the diagnostic reference standard (gold standard). The diagnostic reference standard was established as a diagnosis confirmed by several assays (parasitological and immunological) in accordance with WHO13 and PAHO17,18 criteria. The kappa statistic, calculated using the StatXact 8.0 for Windows software package, was determined to estimate inter-result reliability.

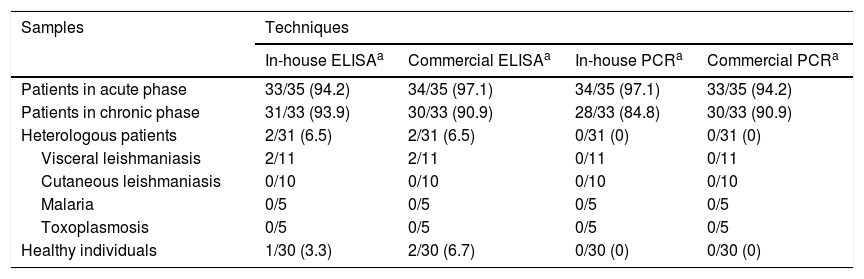

ResultsPositive acute-phase samples gave better results in all assays (immunological and molecular, whether in-house or commercial) than positive chronic-phase samples. Only 3 false positives were observed in the in-house ELISA assay (2 corresponded to individuals with visceral leishmaniasis and one corresponded to a healthy individual) while 4 were observed in the commercial ELISA assay (2 corresponded to the same individuals with visceral leishmaniasis and 2 corresponded to healthy individuals, one of whom was the individual who tested positive with the in-house ELISA assay). No false positives were observed with either the in-house or commercial molecular techniques (PCR) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 of Appendix B).

Detection of anti-Trypanosoma cruzi antibodies using in-house and commercial ELISA assays and detection of T. cruzi DNA using in-house and commercial PCR assays in samples taken from patients with acute-phase and chronic-phase Chagas disease, patients (heterologous) with other parasitic diseases and healthy individuals.

| Samples | Techniques | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-house ELISAa | Commercial ELISAa | In-house PCRa | Commercial PCRa | |

| Patients in acute phase | 33/35 (94.2) | 34/35 (97.1) | 34/35 (97.1) | 33/35 (94.2) |

| Patients in chronic phase | 31/33 (93.9) | 30/33 (90.9) | 28/33 (84.8) | 30/33 (90.9) |

| Heterologous patients | 2/31 (6.5) | 2/31 (6.5) | 0/31 (0) | 0/31 (0) |

| Visceral leishmaniasis | 2/11 | 2/11 | 0/11 | 0/11 |

| Cutaneous leishmaniasis | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 |

| Malaria | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| Toxoplasmosis | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| Healthy individuals | 1/30 (3.3) | 2/30 (6.7) | 0/30 (0) | 0/30 (0) |

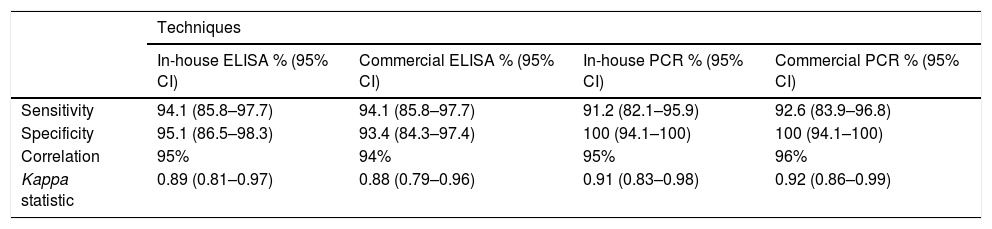

With regards to diagnostic indices, the best sensitivity values were obtained with the in-house and commercial ELISA techniques (94.1%). However, specificity was higher with the in-house and commercial PCR techniques (100%) (Table 2). A high correlation was observed between all the assays performed and the diagnostic reference standard, with the highest correlation observed with the commercial PCR (96%) and the lowest observed with the commercial ELISA (94%), and therefore kappa statistics of 0.92 and 0.88, respectively, were obtained. These kappa statistics show an almost perfect correlation (Table 2).

Diagnostic indices and correlation between in-house ELISA, commercial ELISA, in-house PCR and commercial PCR assays for the diagnosis of Chagas disease.

| Techniques | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-house ELISA % (95% CI) | Commercial ELISA % (95% CI) | In-house PCR % (95% CI) | Commercial PCR % (95% CI) | |

| Sensitivity | 94.1 (85.8–97.7) | 94.1 (85.8–97.7) | 91.2 (82.1–95.9) | 92.6 (83.9–96.8) |

| Specificity | 95.1 (86.5–98.3) | 93.4 (84.3–97.4) | 100 (94.1–100) | 100 (94.1–100) |

| Correlation | 95% | 94% | 95% | 96% |

| Kappa statistic | 0.89 (0.81–0.97) | 0.88 (0.79–0.96) | 0.91 (0.83–0.98) | 0.92 (0.86–0.99) |

Chagas disease in Venezuela (which was under control in the past) is currently considered one of the many re-emerging diseases in the country’s highly deteriorated healthcare situation4. Over recent years, the country has seen an increased incidence and prevalence (shown by recent epidemiological studies2,3,5), reports of acute cases6, an increase in the number of samples testing positive for the disease in blood banks7 and numerous outbreaks of orally transmitted disease8–10. The actual prevalence of Chagas disease in Venezuela is very hard to estimate given the irregularity of the National Chagas Disease Control Programme and its many problems. Some studies of certain areas of the country describe 10%–12% seroprevalence5. Therefore, in this context where the results of the various diagnostic centres and those of the reference laboratories are very different5,7, it is essential to evaluate and compare the diagnostic capacity of the different techniques used.

Due to the potential sensitivity and specificity problems of some assays in certain scenarios, the WHO/PAHO recommend the use of parasitological/molecular assays to confirm acute cases and the use of the “gold standard” (at least two different types of assays and a third technique in the event of discrepancies) in patients with suspected chronic infection. The use of ELISA assays is also recommended in population studies on the prevalence of Chagas disease; ELISA assays (highly sensitive kits) are also recommended for screening for chronic T. cruzi infection in blood banks17,18.

This study evaluated two commercial kits: Chagas ELISA IgG+IgM® (Vircell®, Granada, Spain) and Speed-oligo Chagas® (Vircell®, Granada, Spain). These were compared with the in-house ELISA and PCR methods used by the laboratory. The main difference between the assays is the fact that the in-house ELISA assay uses Maekelt’s T. cruzi antigen (whole parasite protein extract), while the commercial ELISA assay contains recombinant antigens widely evaluated for Chagas disease diagnosis: FRA, B13 and MACH (PEP2 TcD TcE and SAPA)15. Nevertheless, there was no difference in sensitivity and the slight difference in specificity was not significant. However, with regards to molecular diagnosis, the amplification target (T. cruzi satellite DNA) is the same for both the in-house and commercial PCR assays. The difference lies in the detection method, which for the in-house PCR assay is agarose gel electrophoresis, with ethidium bromide staining, while for the commercial PCR assay the detection method used is hybridisation of the PCR product using a reagent strip, which perhaps made the latter slightly (although not significantly) more sensitive than the in-house PCR assay. The specificity of both PCR assays, however, was the same, which was to be expected given that they both have the same amplification target.

Studies evaluating commercial kits have been published in which most of the kits have sensitivity above 98%, with very few having sensitivity below that value. Regarding specificity, most kits have values above 96%–97%, with those kits with recombinant antigens having higher specificity17–20. In this study, as far as false positives are concerned, 2 corresponded to individuals with visceral leishmaniasis and 2 corresponded to healthy individuals (who may perhaps have had a subclinical infection or may have tested positive due to immunological memory following a past infection, even though this is not shown in their medical records). Although all samples, which should be negative, are taken into account for specificity purposes, it is necessary to conduct subsequent studies with a larger number of leishmaniasis samples taken from co-endemic areas since the presence of co-infection has been reported in these areas21,22.

It is very important to consider the epidemiological context in which diagnostic techniques are evaluated since, for example, this study shows that serology detects a higher number of cases in the acute phase than in the chronic phase, which is not the norm in most epidemiological situations. This could be explained by the current healthcare situation in Venezuela as many studies show that re-emerging vector-borne infections, which were under control in the past, have increased in incidence and prevalence2–6. This data suggests that T. cruzi transmission in Venezuela is highly active and therefore there is no obvious difference between the two phases.

Parasite persistence in patients considered to be in the chronic phase and treatment failures have, however, been described. In these cases, parasite persistence is still observed several years after treatment and resolution of acute-phase symptoms23. Follow-up studies of outbreaks of orally transmitted Chagas disease have shown 70% infection persistence six years after anti-parasitic treatment9. This is compatible with the PCR results seen in the chronic phase, where sensitivity is similar to that of the acute phase, which is not common in most cases as PCR sensitivity for amplification of satellite DNA (one of the most commonly used targets worldwide) is around 50% in the chronic phase24. In this situation, definition of the acute phase and chronic phase is therefore complicated. This is why it is necessary to evaluate diagnostic techniques in every individual context.

Evaluation of the commercial Vircell® ELISA kit has only been published in a university thesis25 and in a WHO study on the validation of international reference standards26, with sensitivity and specificity values similar to those obtained in this study. There are no publications on the Speed-oligo Chagas® kit (Vircell®, Granada, Spain).

The diagnostic indices of the commercial kits evaluated were similar to those obtained with the in-house assays and are suitable for diagnosing Chagas disease in endemic areas of Venezuela. The Speed-oligo Chagas® kit (Vircell®, Granada, Spain) avoids the use of hazardous substances like ethidium bromide, which is present in the conventional PCR assay used at some reference laboratories in Venezuela.

FundingThis study was funded by Project DIPISA-PG-2017-004, University of Carabobo.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Viettri M, Lares M, Medina M, Herrera L, Ferrer E. Evaluación de estuches comerciales para el diagnóstico inmunológico y molecular de la enfermedad de Chagas en zonas endémicas de Venezuela. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:82–85.