To implement HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in Spain, several possible models fitting the Spanish National Health System must be considered. The experience of other countries with a similar background let us foresee their benefits and their defects before implementing them. Possible implementation models for prescription-follow-up-dispensing circuits may involve hospitals, STI clinics or primary care centres and community pharmacies. On the one hand, a hospital-based circuit is the least effective of them all and it may not satisfy the potential demand, even though it could be deployed immediately. On the other hand, accessibility would increase with PrEP prescription in Primary care and dispensing by community pharmacists. Involvement of community-based STI clinics and publicly-funded STI clinics would be the best option to attract the population not frequenting the general health system, and co-management with Primary Care teams would ensure nation-wide access to PrEP.

Para implementar la profilaxis preexposición (PrEP) para el VIH en España deben barajarse los diferentes modelos que se ajusten a nuestro Sistema Nacional de Salud. Las experiencias de países con entorno similar permiten adelantar sus beneficios y sus defectos antes de su implementación. Los modelos de implementación posibles para el circuito de prescripción-seguimiento-dispensación podrían implicar hospitales, centros de ITS, centros de Atención Primaria y farmacia comunitarias. Por un lado, el circuito hospitalario es el menos eficiente y presumiblemente no podría satisfacer la potencial demanda, aunque podría ser implantado inmediatamente. Por otro lado, la accesibilidad se ampliaría si su prescripción y dispensación tuvieran lugar desde la Atención Primaria y la farmacia comunitaria. La incorporación de centros de ITS públicos y comunitarios sería la mejor opción para atraer a población no frecuentadora del sistema sanitario general y su gestión compartida con Atención Primaria permitiría el acceso a la PrEP en el territorio nacional.

In 2016, after the favourable opinion of the European Medicines Agency, the European Commission approved the fixed-dose combination of emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (F/TDF) as HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Its price and financing have not yet been defined in Spain. Although these decisions must be made between 180 and 270 days,1 it is normal for the legally established margins to be exceeded,2,3 but exceeding them by 900 days is exceptional. Once the maximum industrial price has been defined and the therapeutic positioning report for PrEP has been issued, the Permanent Commission for the Provision, Insurance and Financing of the NHS Interterritorial Council must decide on the way of financing and implementing this preventive strategy, so that it is applied in each autonomous community.4

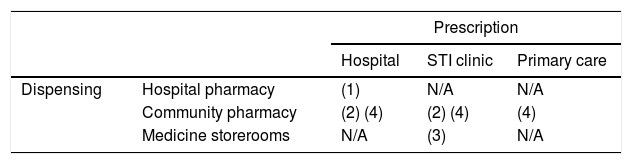

The feasible models of PrEP implementation are diverse, although some would require changes in legislation or prescription and dispensing conditions. The current prescription and dispensing conditions of F/TDF in Spain establish its use in hospitals,5 limiting the healthcare agents involved in its prescription/dispensing circuit to medical and pharmaceutical specialists in the hospital setting. In other countries, general practitioners, specialists in STI clinics, community centre doctors and community pharmacists have also been involved.6–9 Thus, the feasible models will be a combination of the possible prescription and follow-up by doctors in hospitals, STI clinics and primary care centres, and dispensation in hospital pharmacies and community pharmacies (Table 1).

Models of PrEP implementation in Spain in terms of its prescription/dispensing circuit.

| Prescription | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | STI clinic | Primary care | ||

| Dispensing | Hospital pharmacy | (1) | N/A | N/A |

| Community pharmacy | (2) (4) | (2) (4) | (4) | |

| Medicine storerooms | N/A | (3) | N/A | |

Those models that comply with current legislation and records are indicated with (1); those which need to introduce exceptions in the dispensation, contemplated in other hospital dispensed drugs, are indicated with (2); those with extraordinary outpatient dispensing in storerooms are indicated with (3); those which need changes in the prescription and dispensing conditions of the medication are indicated with (4).

N/A: not applicable.

1. Prescription by doctors of HIV hospital units and dispensing in hospital pharmacy services. This is the model that best suits the authorised conditions of prescription and dispensation, and current legislation. For the implementation thereof, the inclusion of the indication of F/TDF as PrEP in the pharmacotherapeutic guidelines of the hospitals will suffice. The advantages of this model are: the high degree of specialisation of prescribers and dispensers; the existence of hospital healthcare resources throughout the territory, and the centralised registration of data within the programme. This model, however, is the least efficient for the NHS, since it employs highly specialised healthcare resources that could be saturated by having to care for a healthy population vulnerable to HIV in the programme,10 in addition to patients being treated for HIV; It would also mean less accessibility and a delayed start. In addition, hospital dispensing makes it difficult to establish co-payment or a payment associated with the dispensing. This model is similar to that used in Portugal,9 in which the volume of beneficiaries of the PrEP public programme is small, with around 300 users in the entire country.

2. Prescription by STI clinic specialists and dispensing in the medication storeroom of the clinic itself. Legally, storerooms are intended for the provision of medicines for residents or patients of the health and social centres for their on-site administration.11 Currently, the special dispensing model for outpatient medication in storerooms is only given with methadone.12 The necessary requirements for its implementation include the establishment of agreements between the STI clinics and the pharmacy departments or community pharmacies, the adaptation of the facilities (reception area of goods, storage, dispensing and management), the assignment of pharmacy personnel to ensure the proper functioning of the storeroom and the relevant regional administrative authorisation. It should be remembered that STI clinics do not constitute legally authorised entities for the dispensing of medicines to the public, but for the provision of health services and the medication associated to the same.13

Despite these difficulties at a technical-legal level, the advantages of this model are that it facilitates accessibility to the health resource, and the acceptance of this type of resource by people reluctant to receive assistance in general health centres.14 This implementation model is the one applied in England for the provision of PrEP to around 10,000 participants of the IMPACT study, but it is not used in Scotland, where the provision of PrEP in its health system has been standardised.7 In Spain, it is one of the models evaluated in the feasibility study of PrEP promoted by the multicentre National Plan on AIDS, in which the BCN PrEP-Point community centre participates, along with other hospitals and publicly owned STI clinics.15 However, this model could only be implemented in territories where there are public or subsidised STI clinics associated with non-governmental organisations, so solutions would need to be found for the other territories.

3. Prescription by medical specialists in hospitals or STI clinics and dispensing in community pharmacies. In this model, the registration of F/TDF could be maintained as a medicine for hospital use, but to facilitate access, the medicine would be dispensed in a community pharmacy. This model has already been proposed for maintenance treatments with methadone16 and with standardised cannabinoid extracts.17

The AEMPS (Spanish Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices) should authorise community pharmacists to deliver the medication and provide the associated pharmaceutical care. This model combines the high degree of specialisation of prescribers in STI clinics in many provinces (in the absence thereof, in hospital STI units) with easy access for users to medication in the pharmacy community, where there is extensive experience in damage reduction programmes (such as the syringe exchange programme,18 the maintenance treatment with methadone,12 in the treatment directly observed in tuberculosis,19 etc.). In addition, it would make it possible to establish a co-payment for the medication, when necessary, to promote the sustainability of the system. A network of STI units and community pharmacies would need to be created to ensure accessibility and proximity of the resource to those who can benefit from it, and the requirements of community pharmacists for the dispensing of F/TDF would need to be defined, with complementary training to homogenise pharmaceutical care and centralised data recording.

4. Prescription by Primary Care specialists and dispensing in community pharmacies. This model requires that the AEMPS be asked to change the conditions of prescription and dispensation authorised for F/TDF, from medication for hospital use to medication subject to medical prescription, or hospital diagnostics medication, with follow-up in Primary Care in both cases. This model guarantees the accessibility, proximity and capillarity of Primary Care centres and community pharmacies for PrEP programmes; it makes it possible to establish a co-payment or payment for dispensing the medication if necessary and takes advantage of the experience of community doctors and pharmacists in the application of preventive strategies. In this case, complementary training for physicians and pharmacists on PrEP and sexual diversity would be appropriate, to homogenise the care practice and promote the destigmatisation of healthcare around HIV and the prevention thereof.

In France, F/TDF is included in the liste I (prescription initiale hospitalière annuelle et prescription par un médecin exerçant en CEGIDD),6 similar to hospital diagnostic drugs: an HIV specialist prescribes the first time, and the follow-up is conducted by doctors from STI clinics (CEGIDD in France) and in Primary Care. This system provides coverage for more than 10,000 people in France, with relatively easy access and cost reimbursement.

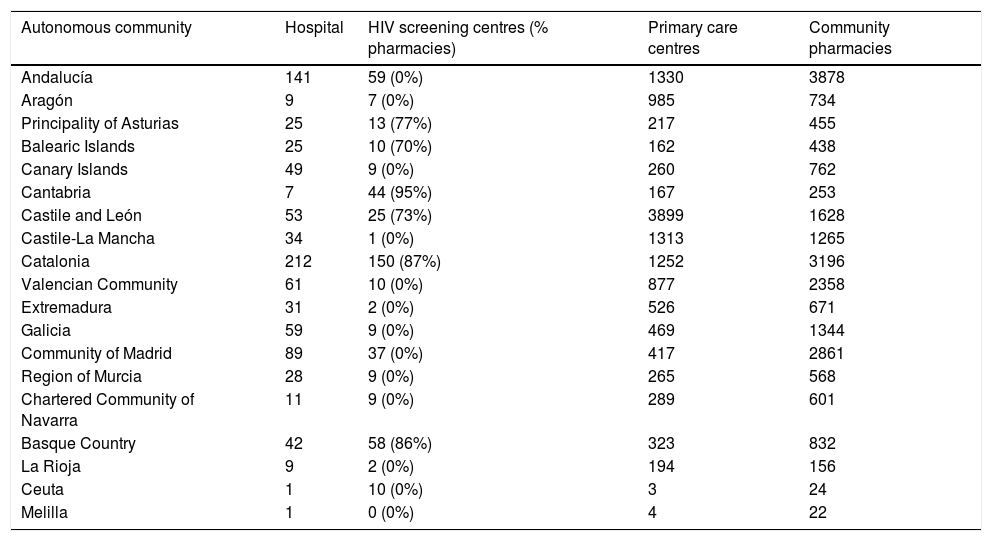

DiscussionHIV detection programmes outside the hospital environment have demonstrated a great capacity to constitute a relevant strategy in certain population groups, such as men who have sex with men, the high visibility thereof being a key factor in attracting both people with high probability of exposure to HIV that have never been tested before, and highly specific and vulnerable populations that are not captured by standardised health services.14 One of the most consistent points in favour of conducting health checks and prescribing PrEP in community centres or centres specialised in screening and diagnosis of STIs is the ability to capture vulnerable populations reluctant to go to other types of health services. This has been evidenced in the informal use of PrEP in Spain with the good acceptance of the programmes seguiPrEP of BCN PrEP-Point20 and PrevenPrEP of Adhara Sevilla Checkpoint.21 The involvement of these pioneering centres is crucial to the success of any implementation model in Spain. Both public and community-run STI clinics are available in virtually all autonomous communities, although they tend to be concentrated in large urban centres (Table 2).

Health resources for the control of HIV and STIs in Spain by cities and autonomous communities.

| Autonomous community | Hospital | HIV screening centres (% pharmacies) | Primary care centres | Community pharmacies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalucía | 141 | 59 (0%) | 1330 | 3878 |

| Aragón | 9 | 7 (0%) | 985 | 734 |

| Principality of Asturias | 25 | 13 (77%) | 217 | 455 |

| Balearic Islands | 25 | 10 (70%) | 162 | 438 |

| Canary Islands | 49 | 9 (0%) | 260 | 762 |

| Cantabria | 7 | 44 (95%) | 167 | 253 |

| Castile and León | 53 | 25 (73%) | 3899 | 1628 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 34 | 1 (0%) | 1313 | 1265 |

| Catalonia | 212 | 150 (87%) | 1252 | 3196 |

| Valencian Community | 61 | 10 (0%) | 877 | 2358 |

| Extremadura | 31 | 2 (0%) | 526 | 671 |

| Galicia | 59 | 9 (0%) | 469 | 1344 |

| Community of Madrid | 89 | 37 (0%) | 417 | 2861 |

| Region of Murcia | 28 | 9 (0%) | 265 | 568 |

| Chartered Community of Navarra | 11 | 9 (0%) | 289 | 601 |

| Basque Country | 42 | 58 (86%) | 323 | 832 |

| La Rioja | 9 | 2 (0%) | 194 | 156 |

| Ceuta | 1 | 10 (0%) | 3 | 24 |

| Melilla | 1 | 0 (0%) | 4 | 22 |

At present, the correlation between the effectiveness of PrEP and the proper use of medication by users is well established. Although, as explained above, the implementation of PrEP services could be conducted without major regulatory modifications in STI clinics and hospital centres,9 the remoteness of some users’ homes from these centres, along with the need to carry out routine health check-ups, could result in loss of follow-up or suboptimal use of PrEP by these users.

Considering the characteristic capillarity of the Spanish health system, the inclusion of Primary Care centres and pharmacies into the PrEP monitoring-control-dispensing circuit6 would most likely guarantee access to PrEP throughout the territory, and the reduction of the potential stigma associated with the use of PrEP,22 by including it in the usual prescription and dispensing circuit. For some users, a PrEP programme can also act as a gateway to standardised health systems,23 to offer them vaccination campaigns, smoking cessation, screening, etc. The participation of pharmacies also makes it possible to extend the coverage of harm reduction and disease screening programmes to all types of social centres.14,24

The PrEP implementation model eventually implemented in Spain must introduce equity in access25 so that those most vulnerable to HIV can use PrEP, regardless of their financial resources or the degree of sensitivity that health workers may present before the sexual diversity of their patients. With this in mind, there would seem to be a clear need to incorporate Primary Care teams and community and public STI clinics in order to ensure the success of PrEP programmes in Spain.

FundingWithout funding

Authors’ contributionJ.F. Mir, M.F. Mazario and J. Coll conceived and designed the work.

J.F. Mir wrote the article and M.F. Mazario and J. Coll conducted a critical review with important intellectual contributions.

J.F. Mir, M.F. Mazario and J. Coll approved the final version of the article for publication.

J.F. Mir, M.F. Mazario and J. Coll take responsibility for and guarantee that all aspects that make up the manuscript have been reviewed and discussed among the authors in order for them to be expounded with the utmost precision and integrity.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank Michael Meulbroek and Ferran Pujol for their efforts to set up the BCN PrEP-Point Centre to improve access to PrEP in the city of Barcelona.

Please cite this article as: Mir JF, Mazarío MF, Coll P. Modelos de implementación y acceso a la profilaxis preexposición para el VIH en España. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2020;38:234–237.