I read with interest the article, "Invasive pulmonary fungal infection and rhinofacial cellulitis with paranasal sinus and orbital fossa invasion in an immunocompromised patient", and I would like to thank the authors for reporting such cases, as the incidence is low in our setting and I think publishing them helps improve management of these patients.1

As described in the article, invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is a potentially fatal disease, with mortality rates of up to 72%, according to the published series.2 This disorder is classified into three categories: granulomatous; chronic; and acute fulminant. Acute fulminant is the most serious and occurs almost exclusively in immunosuppressed patients.3

The most common causal agents of this infection are Aspergillus, Rhizopus and Mucor spp., and it is spread by inhalation of spores.4 There are other less common forms of presentation, such as conidiobolomycosis caused by Conidiobolus coronatus described in the publication, where invasion of the paranasal sinuses can occur by inhalation or through the subcutaneous space.5

This disorder should be suspected in patients with symptoms consistent with acute rhinosinusitis, particularly if they are associated with complicating clinical data such as facial and periorbital oedema, proptosis, decreased visual acuity or cranial nerve palsy. In these cases, although it has not been reported on, a nasal endoscopic examination and a CT of the brain and paranasal sinuses are necessary. MRI should be considered if orbital or intracranial complications are suspected.

Since the condition can worsen rapidly, as in the case of the patient described, an accurate initial assessment is essential. In these situations, it would be advisable to consult an ENT specialist urgently to rule out foci of fungus colonisation in the upper airway, in addition to targeted imaging tests such as those mentioned above.

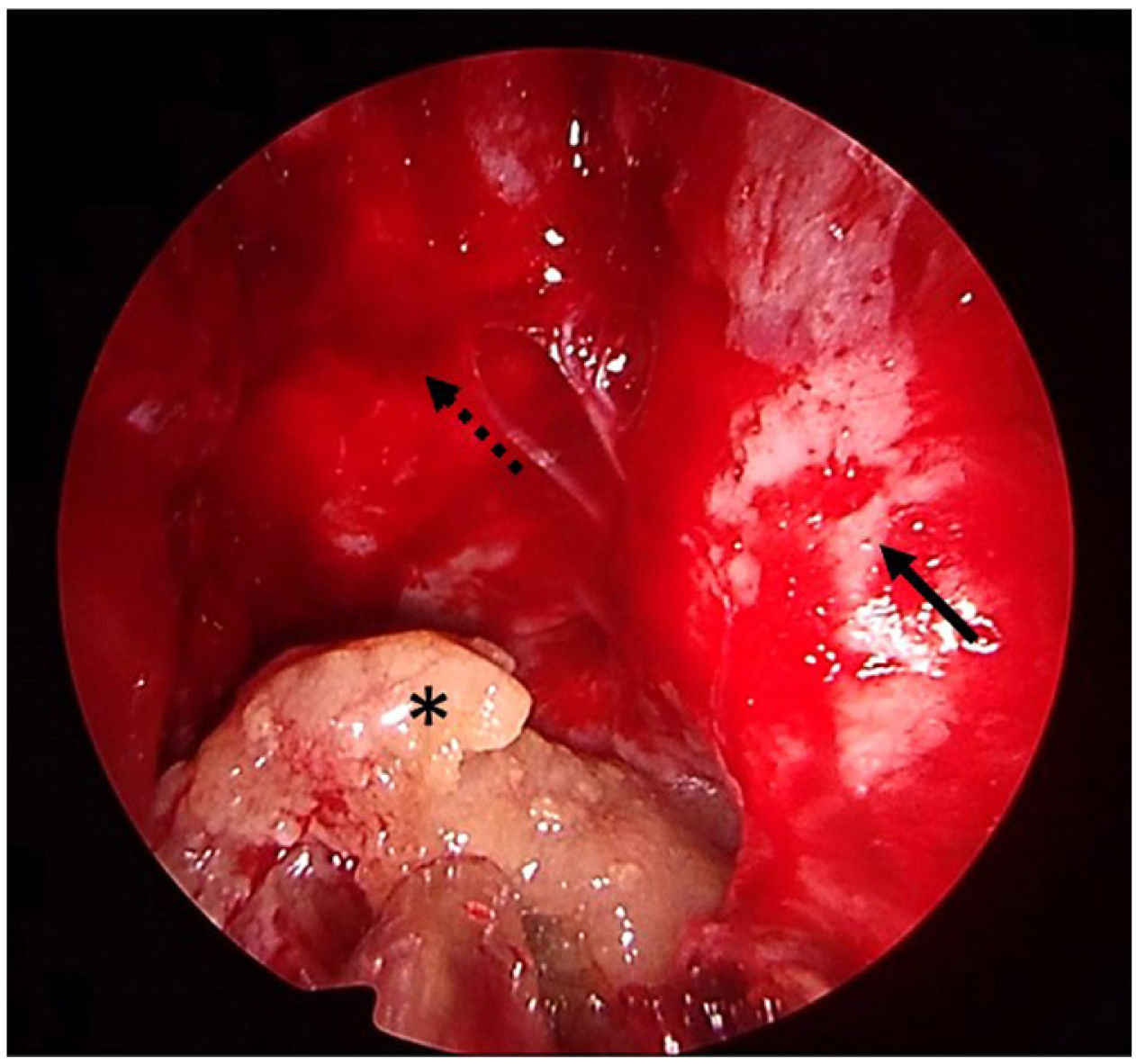

In all patients diagnosed with, or in any patient suspected of having, invasive fungal sinusitis, urgent aggressive endoscopic sinus debridement should be considered, in addition to intravenous antifungal therapy and reversal of underlying immunosuppression.6Fig. 1 shows the last case treated in our department. This patient had invasive fungal rhinosinusitis caused by Aspergillus welwitschiae, with clivus and left orbital involvement, and underwent ethmoidal and sphenoidal debridement plus antifungal therapy with amphotericin B 10mg/kg/day combined with posaconazole 300mg/24h. The patient had a satisfactory outcome after treatment.

Early surgical treatment of the paranasal sinuses has been shown to improve the survival rate, delay disease progression, reduce fungal load and provide a specimen for culture and histopathology diagnosis.7 Despite these measures, the prognosis is extremely poor if the host's immune response does not improve.8 In cases where the patient's prognosis is poor due to their underlying disease, and more aggressive debridement is required which includes external maxillectomy or orbital exenteration, the indication for intervention has to be agreed by a multidisciplinary group with the patient.

An interesting development has been the recent publication of several articles that report an increase in the incidence of invasive fungal sinusitis in relation to SARS-CoV-2 disease (COVID-19). The predisposing cause is still unknown. It is thought that several factors may be involved, such as the increased use of corticosteroids, broad-spectrum antibiotics and nosocomial infections. Increased serum ferritin levels, endothelial damage and pancreatic islet disease in patients with COVID-19 may also be involved.9

Awareness of the growing prevalence of invasive fungal sinusitis in our setting and proper management of this disease can help early diagnosis and treatment, which is essential if we are to improve the prognosis for these patients.