We read with great interest the article by Sanz et al.1 in which they demonstrated the usefulness of IgM detection (DiaSorin, Italy) in confirming cases of measles, using a high-sensitivity, high-specificity method that carries potential advantages in implementation in routine emergency medical care and in microbiology departments. According to the authors, the study had some limitations, such as its limited sample size and the manner of selection of the control group. However, in our opinion there is a matter of particular interest: determining patients' pre-exposure immune situation—that is to say, their measles virus vaccination status.

In Spain, systematic measles vaccination was introduced in 1975, with one dose at the age of nine months. Subsequently, between 1988 and 1995, a second dose at 11 years of age was included and total coverage was achieved in 1995. In 2000, the vaccination schedule was modified to include a first dose of a measles-mumps-rubella vaccine at the age of 12 months and a second dose at the age of 3–4 years. This regimen remains in place today.

This prior immunisation influences the immune response to the infection, which is characterised as a secondary response, with lower IgM production and, therefore, a lower likelihood of detection, and with a rapid and significant increase in IgG2.

In this regard, we would like to offer our experience in a measles outbreak in an occupational setting in March 2018. The outbreak consisted of 10 cases, nine of which were healthcare personnel at a tertiary hospital.

The index case corresponded to a 34-year-old man who visited primary care due to a fever of 39 °C and a rash that spread downwards from his face, sparing the palms of his hands and the soles of his feet, with associated odynophagia and cough. Examination revealed palpable lymphadenopathy behind the ears. The patient was diagnosed with acute tonsillitis and prescribed antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. Five days later, as a result of worsening due to respiratory failure, he required hospital admission.

As measles was suspected, respiratory and contact isolation were indicated. The diagnosis was confirmed by means of serology, with IgM(+) and IgG(−), and by the presence of RNA in a nasopharyngeal sample (genotype B3). In addition, alveolar infiltrate was seen in the right upper lobe, and treatment with levofloxacin was started due to probable bacterial superinfection. He was discharged after eight days, having followed a suitable clinical course.

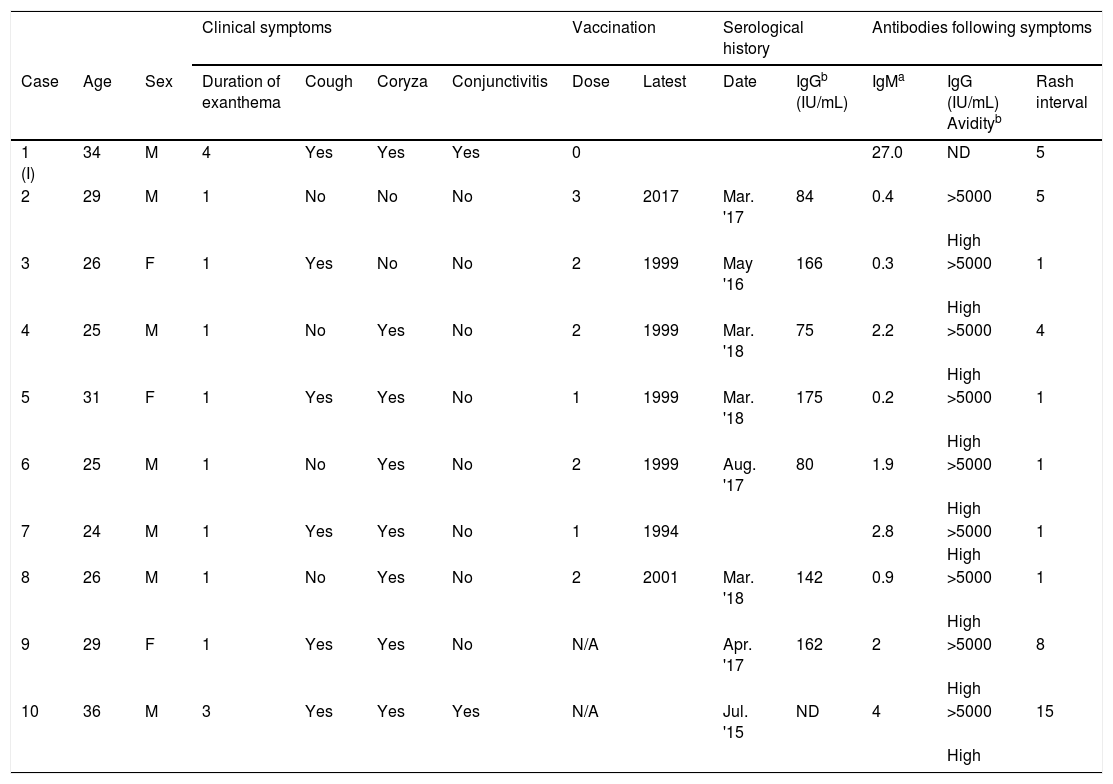

Nine secondary cases occurred amongst the healthcare personnel who treated the patient prior to implementation of isolation measures. Of them, 66.6% were women, and their mean age was 27.8 years (range 24–36). In all cases, a skin rash developed; in eight of the nine cases, it lasted one day. Cough was present in five cases, coryza in seven cases and conjunctivitis in one case (Table 1).

Clinical data and relevant vaccination history of patients affected by the outbreak and serological results before and after the onset of measles virus infection.

| Clinical symptoms | Vaccination | Serological history | Antibodies following symptoms | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Age | Sex | Duration of exanthema | Cough | Coryza | Conjunctivitis | Dose | Latest | Date | IgGb (IU/mL) | IgMa | IgG (IU/mL) Avidityb | Rash interval |

| 1 (I) | 34 | M | 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 | 27.0 | ND | 5 | |||

| 2 | 29 | M | 1 | No | No | No | 3 | 2017 | Mar. '17 | 84 | 0.4 | >5000 | 5 |

| High | |||||||||||||

| 3 | 26 | F | 1 | Yes | No | No | 2 | 1999 | May '16 | 166 | 0.3 | >5000 | 1 |

| High | |||||||||||||

| 4 | 25 | M | 1 | No | Yes | No | 2 | 1999 | Mar. '18 | 75 | 2.2 | >5000 | 4 |

| High | |||||||||||||

| 5 | 31 | F | 1 | Yes | Yes | No | 1 | 1999 | Mar. '18 | 175 | 0.2 | >5000 | 1 |

| High | |||||||||||||

| 6 | 25 | M | 1 | No | Yes | No | 2 | 1999 | Aug. '17 | 80 | 1.9 | >5000 | 1 |

| High | |||||||||||||

| 7 | 24 | M | 1 | Yes | Yes | No | 1 | 1994 | 2.8 | >5000 | 1 | ||

| High | |||||||||||||

| 8 | 26 | M | 1 | No | Yes | No | 2 | 2001 | Mar. '18 | 142 | 0.9 | >5000 | 1 |

| High | |||||||||||||

| 9 | 29 | F | 1 | Yes | Yes | No | N/A | Apr. '17 | 162 | 2 | >5000 | 8 | |

| High | |||||||||||||

| 10 | 36 | M | 3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Jul. '15 | ND | 4 | >5000 | 15 | |

| High | |||||||||||||

I: index case of the outbreak; N/A: no existing vaccination record; ND: not detectable.

Cases were confirmed by means of serology, by seroconversion, an at least fourfold increase in high-avidity IgG titre (>5000) (Euroimmun, Germany), a few days after the onset of the rash, which indicated a booster due to prior immunity. IgM was positive in just five cases (55%) and close to the cut-off point in all cases, in contrast to the index case, who had no history of vaccination. In addition, in three of the cases, the viral RNA detected (from a nasopharyngeal sample) belonged to genotype B3—the same genotype as in the index case. There is no record of any tertiary cases in this outbreak.

Investigation of vaccination status revealed that six patients had received at least one dose of the triple viral vaccine and eight patients had a serological determination of measles (IgG) less than 200 mIU/mL (Euroimmun, Germany) prior to contact with the index case.

In vaccinated people, it is more difficult to detect cases of measles according to microbiological criteria, both because the short period of viral replication makes it difficult to detect viral RNA and because IgM has a weaker presence3,4. This highlights the need to detect high-avidity IgG seroconversion within a few days of the onset of the rash through an at least fourfold increase in its titre, which demonstrates the “booster effect”5,6.

Surveillance of suspected cases of measles-like disease or atypical measles, with common signs and symptoms of limited duration tending to affect young vaccinated individuals, is a major challenge. Such cases may be underdiagnosed, as they are often detected in contact tracing following confirmation of a classic case of measles. In addition, the appearance of these signs and symptoms in countries with high vaccination coverage, such as Spain, points to suboptimal protection due to insufficient vaccine doses or loss of immunity over time7,8.

These particular characteristics of measles necessitate new seroprevalence studies in countries with high vaccination coverage, especially in the young adult population, to identify potentially vulnerable groups by detecting low or absent levels of antibodies9. Protection of this at-risk population, in particular people who may come into contact with classic measles such as health workers, could bear reconsideration of the measles vaccination programme.

Please cite this article as: Navalpotro-Rodríguez D, Garay-Moya Á, Chong-Valbuena A, Melero-Garcia M. Brote de sarampión-modificado en personal sanitario tras exposición a un caso de sarampión clásico. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:342–343.