Parvimonas micra, formerly Peptostreptococcus micros and Micromonas micros, are anaerobic, gram-positive cocci that belong to the abdominal, oropharyngeal and genitourinary flora, commonly related with periodontal diseases.1 Its pathogenicity has been also documented in disseminated diseases such as septic arthritis, spondylodiscitis or abscesses in different organs.2–4 In 2015 the first case of endocarditis was described, in a 71-years-old male patient with valve abscess.1 A literature review showed two cases of infectious endocarditis due to P.micra1,5 and three cases related to their ancestor P. micros.6–8

We present a case of infectious endocarditis in a woman with a pacemaker and prosthetic mitral valve.

A 63-year-old female presented at the emergency department with a history of one month of persistent fever at dawn and noon, with chills, diaphoresis, asthenia and weight loss (5kg). She denied dental procedures, recent interventions or invasive diagnostic techniques. Oral evaluation was made with no signs of periodontal disease other than edentulism. There were no respiratory, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal or urinary symptoms and no cutaneous manifestation were found.

She had frequent follow-ups with neurosurgery and neurology for a right cerebral subependymoma and a mid-cerebral artery cardioembolic ictus performed eleven months prior to this episode. She had had a mechanical prosthetic mitral valve replacement in 1990. She had frequent checkups with urology for kidney angiomyolipomas.

On examination, temperature was normal, blood pressure was 130/62mmHg, pulse of 70 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 100%. Auscultation was clear with no remarkable finding except for a click in the mitral valve. No lymphadenopathies were noted, as well as no edemas, with low muscle mass. The remainder examination was normal.

The patient was hospitalized to study a fever of unknown origin, and an echocardiography and positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) were done. The PET/CT showed metabolic signs of infection in mitral prosthetic and periprosthetic tissue with moderate increased tracer uptake at the right carotid artery, aortic arch, thoracic aorta and pulmonary arteries compatible with active vasculitis on the large vessels. No pacemaker or extracardiac deposites were found.

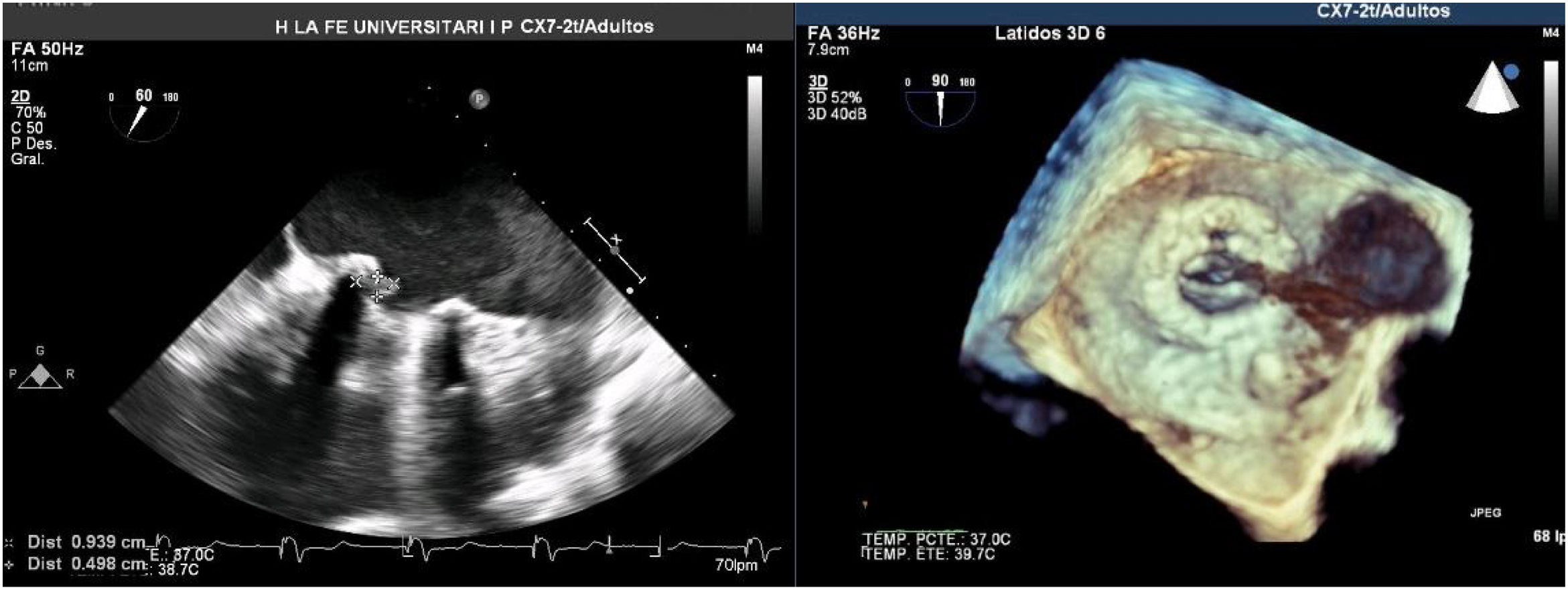

A Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) showed a vegetation on the medial side of the prosthetic ring of about 8mm (Fig. 1). Cardiac and aortic CT discarded the possibility of valvular abscess or aortitis.

During the first 5 days of hospitalization 3 blood cultures were taken and incubated in BACT/ALERT® VIRTUO® (bioMérieux). After 43.94h of average incubation (44.88h – 42.82h – 44.13h) in the anaerobic media growth of gram-positive cocci identified by MALDI-TOF® as P. micra. The antibiotic susceptibility was done using Epsilon test in Columbia blood agar supplemented with 5% lamb defibrinated blood, in anaerobic atmosphere, obtaining the following MIC (mg/L) profile: penicillin 0.016, ampicillin 0.032, amoxicillin-clavulanic 0.047, ceftriaxone 0.125, imipenem 0.012, clindamycin 0.094, vancomycin 0.38, levofloxacin 0.19, rifampicin 0.002.

Empiric treatment was started with ceftriaxone and gentamycin and later modified to penicillin and clindamycin after culture isolation. The first negative blood culture was 4 days after initial treatment. TEE showed vegetation stability without complications, so it was decided to manage the case conservatively, with outpatient orally treatment with ceftriaxone and rifampicin for 6 more weeks. The evolution was favorable with negative control of blood cultures up to one year after the episode. After a year follow up by the Rheumatology Department the conclusion was that, findings on the PET/CT scan were due to the inflammatory response to the infection, which diminished on subsequent scans.

Endocarditis is mainly caused by species of the genus Streptococcus and Staphylococcus, comprising around two-thirds of the total of infectious endocarditis, while anaerobic organisms are only isolated in 2–16% of the cases.9 Predominant anaerobic species are Cutibacterium acnes, Bacteroides fragilis and Clostridium spp.10 Endocarditis due to Peptostreptococcus spp. are infrequent10 with P. magnus being the most common species.9 If we focus on P. micra, until now five cases have been described in the literature,1,5–8 only two of them encompassed within this terminology.1,5

Conflict of interestNone.