The patient was a 56-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and partial hepatectomy and cholecystectomy due to a hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosed two years before. He presented at the emergency department with a three-day history of fever accompanied by chills, generalized joint pain and dyspnea. He had no diarrhea, expectoration, urinary symptoms, or skin lesions, so the working diagnosis was a bloodstream infection with a probable abdominal focus. The sediment was not abnormal, and abdominal ultrasonography ruled out cholelithiasis and bile duct obstruction. Two peripheral blood samples were started, and empirical antibiotic treatment with meropenem was initiated.

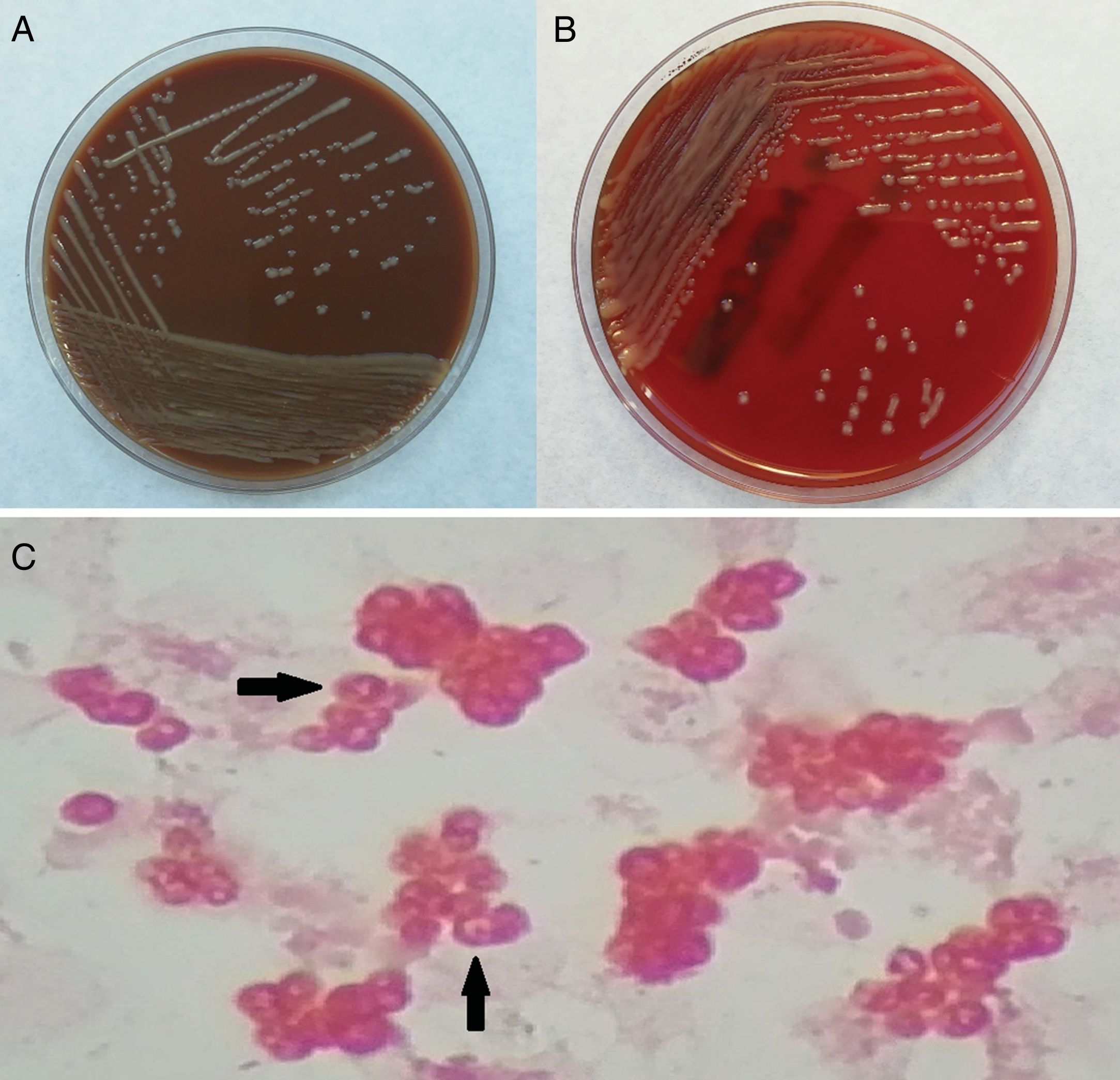

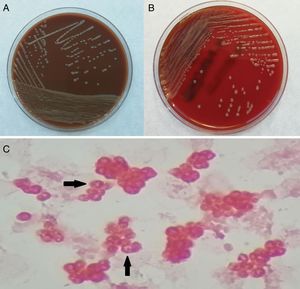

Two blood cultures, both aerobic bottles, were positive after 41h of incubation (BacT/ALERT®, Biomérieux). Direct Gram staining of the blood culture revealed moderate-sized, gram-negative cocci with a characteristic vacuolated appearance (Fig. 1). Blood cultures were transferred to chocolate and blood agar plates and incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere with 5% CO2. Two days later, shiny brown, mucoid, non-hemolytic colonies were observed on the plates (Fig. 1). Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) identified the bacteria as Paracoccus yeei (P. yeei) with a score value of 2.212. Bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified and sequenced using universal primers 27 F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TA CGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). The obtained sequence was compared with data available from GenBank using BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and a 99% identity with the P. yeei CCGU 32053 16S rRNA sequence was found.

Susceptibility testing was performed using the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) microdilution method (Microscan WalkAway, Beckman coulter). As no interpretative criteria have yet been published for P. yeei, we followed the Pseudomonas spp. EUCAST breakpoints for aminoglycosides, quinolones and piperacillin-tazobactam and PK-PD (Non-species related) EUCAST breakpoints for the rest.1 The MIC values were as follow (all of them susceptible): piperacillin-tazobactam: ≤8μg/mL, ceftazidime: ≤1μg/mL, cefepime: ≤1μg/mL, aztreonam: 4μg/mL, meropenem: ≤1μg/mL, amikacin ≤8μg/mL and ciprofloxacin ≤0.5μg/mL. Although others have reported strains resistant to ciprofloxacin2 or to third-generation cephalosporins,3 our strain was sensitive to these antibiotics.

In the days after the initiation of antibiotic treatment, the patient's condition improved and follow-up blood cultures were negative. At discharge, the patient was prescribed ciprofloxacin for two weeks.

P. yeei, which is classified within the family Rhodobacteraceae, are gram-negative, obligate aerobic, nonfermenting cocci or coccobacilli with a characteristic vacuolated or O-shaped appearance in Gram staining. Colonies grow after 24h of incubation on blood and chocolate agar but not on MacConkey agar. Regarding the biochemical profile, it is catalase and oxidase positive and reduce nitrates.4

Since the natural habitat of this bacteria has not been fully defined, it is difficult to predict which patients are at risk of infection. In our patient, the diagnosis was oriented toward sepsis due to an abdominal source, although no abdominal focus of infection had been clearly established. Immunosuppression and certain environmental factors play a decisive role in the pathogenicity of this microorganism, although in our case, the patient's liver function was adequate and there was no evidence of immunodepression.

Bacterial infections are much more common in patients with cirrhosis than in the general population due to the increased inflammatory response and dysregulation of the immune system.5P. yeei is unique within the genus because it has been associated with opportunistic human infections. Most reported cases are infections in immunosuppressed patients, most commonly peritonitis in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis.2,3,6,7 Other reported infections include myocarditis in a heart transplant recipient,8 keratitis in patient who used contact lenses,9 and septic arthritis.

To our knowledge, only two cases of bacteremia due to P. yeei have been reported. In one, the source was bullous lesions4; in the other, a patient with decompensated cirrhosis, the source was unidentified but presumably an abdominal focus.10 Our patient had histologically confirmed cirrhosis, but no clinical, laboratory, or imaging signs of decompensation, despite a prior history of hepatocellular carcinoma. Like some other patients with P. yeei infections, he also had diabetes mellitus, a known risk factor for infections.

It is possible that infections caused by P. yeei are underdiagnosed due to low clinical suspicion, given the scant reports in the literature and the low a priori pathogenic potential for this microorganism. In addition, its macroscopic appearance with colonies initially resembling those of a coagulase-negative staphylococcus may lead to the misidentification of the strain if no further investigations are performed.

In recent years, the use of new molecular techniques such as MALDI-TOF MS has led to an increase in the identification of little known microorganisms as the cause of infections. The present case of bacteremia due to P. yeei confirms the role of this microorganism as a potential source of infection in humans.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Juan José González López (Microbiology Laboratory, Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain) for sequencing the bacterial 16S rRNA gene.