Candida auris is an emerging yeast first reported in Japan in 20091. Since then, its spread has been alarming, with cases reported in more than 30 countries on five continents2. One of the characteristics that distinguishes it from other yeasts is its multidrug-resistant nature, which limits treatment options. Its rate of resistance to fluconazole is notably high — around 90% — and resistance to all antifungals to a greater or lesser extent has been reported. According to recent studies, rates of this resistance are around 12% for amphotericin B and caspofungin, and around 1% for micafungin and anidulafungin2. It is also possible for resistance to develop during treatment with antifungals2. In addition, the emerging nature of this species complicates its laboratory detection, as many commercial systems are unable to detect it3.

We report a case of recurrent candidaemia due to Candida albicans, Candida parapsilosis and C. auris. In addition, C. auris developed resistance to echinocandins during treatment with anidulafungin: this is the first case of echinocandin-resistant C. auris reported in Spain.

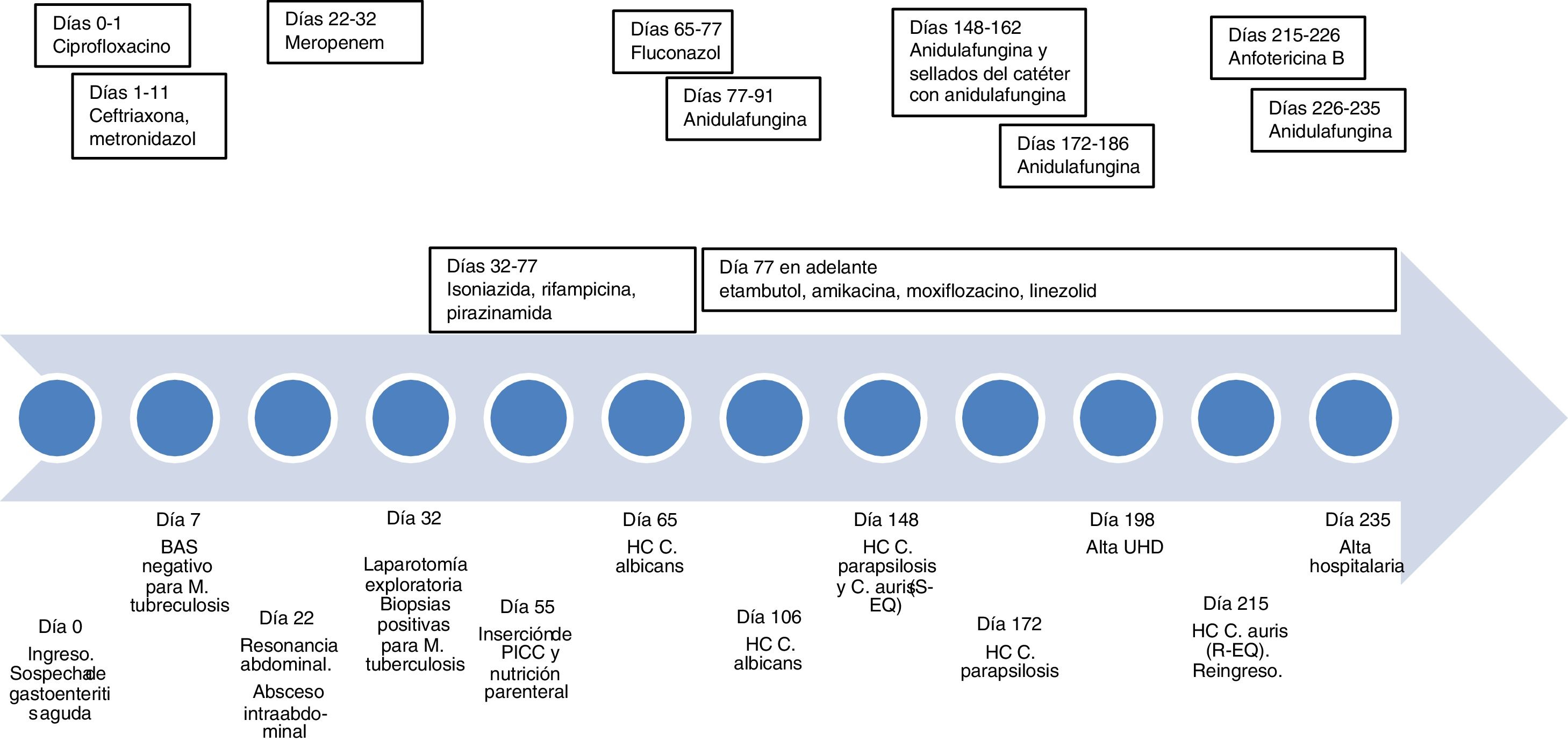

A 21-year-old man of Bolivian origin with no personal history of note visited the accident and emergency department due to abdominal pain, diarrhoea and fever. Initially, acute gastroenteritis was suspected. His mother had suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis treated three years earlier. Examination revealed pulmonary infiltrates indicative of a diagnosis of tuberculosis; hence, he was admitted to the infectious disease department. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing on bronchial aspirate (BAS) and bronchial brushing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Xpert® MTB/RIF Ultra, Cepheid), as well as an interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) test (QFT-Plus, Qiagen), were negative, and therefore pulmonary tuberculosis was ruled out. On day 22 of his stay, after neither his fever nor his abdominal signs and symptoms improved, he underwent abdominal magnetic resonance imaging, which revealed an intra-abdominal abscess. His clinical picture showed no improvement in spite of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, so on day 32, an exploratory laparotomy was performed and samples were taken. As these samples were positive for M. tuberculosis, he was diagnosed with intestinal miliary tuberculosis. The patient needed prolonged admission due to an enterocutaneous fistula as a complication of surgery and a nutritional deficiency which required a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) to be placed to administer parenteral nutrition (day 55).

On day 65, C. albicans was isolated in blood cultures, whereupon the PICC was changed and fluconazole was administered. On day 77, due to abnormal liver panel results, the patient was switched from his current tuberculosis treatment (rifampicin and isoniazid) to a second-line regimen (ethambutol, amikacin, moxifloxacin and linezolid). In addition, fluconazole was switched to anidulafungin, which was stopped on day 91. On day 106, the patient had another episode of candidaemia due to C. albicans and was again treated with anidulafungin for 14 days, and his PICC was replaced with a long-term central venous access catheter in anticipation of his discharge to the home hospitalisation unit. However, on day 148, he developed a fever and his blood cultures tested positive once again. Following subculture of the positive blood culture on the CHROMagar® Candida chromogenic medium (Becton Dickinson), two colony morphologies were seen in this case, both white/pink after 48 h of incubation; they were identified as C. parapsilosis and C. auris using mass spectrometry (Bruker). Treatment with anidulafungin was administered for 14 days and antifungal lock therapy with the same agent was used, but on day 172, colonisation of the catheter by C. parapsilosis persisted, and therefore once again anidulafungin was administered for 14 days and the reservoir was changed. On day 198, the patient was discharged to the home hospitalisation unit.

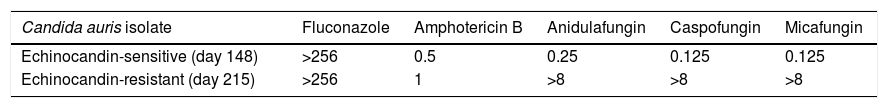

On day 215, he was readmitted due to fever. C. auris was again isolated in the blood culture through the catheter. Given his prior complications, the catheter was removed and parenteral nutrition was suspended. Anidulafungin was started, but after two days, antifungal susceptibility testing showed high levels of resistance to echinocandins, and therefore the patient’s antifungal treatment was switched to amphotericin B. The sensitivity of all isolates was determined by means of microdilution with the Sensititre® YeastOne® Y09 system (Thermo Fisher). For the echinocandin-resistant strain, it was determined in duplicate and also determined in duplicate using the Vitek 2® AST-YS07 system (bioMérieux), which confirmed resistance. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values obtained are shown in Table 1. On day 226, due to an episode of vomiting and nephrotoxicity associated with amphotericin B, anidulafungin was again administered. On day 227, due to weight loss, a decision was made to reintroduce parenteral nutrition; on this occasion, it was not associated with complications, and on day 235, the patient was discharged. Fig. 1 (see Additional materials) shows the timeline of the case.

Sensitivity to antifungals determined using Sensititre® YeastOne® Y09 (MIC values in mg/l) of C. auris strains isolated.

| Candida auris isolate | Fluconazole | Amphotericin B | Anidulafungin | Caspofungin | Micafungin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echinocandin-sensitive (day 148) | >256 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| Echinocandin-resistant (day 215) | >256 | 1 | >8 | >8 | >8 |

The patient had several known risk factors for developing candidaemia: abdominal surgery, parenteral nutrition, catheter use and prolonged broad-spectrum antibiotic and antifungal treatment4. In addition, prolonged treatment with anidulafungin might have promoted selection of resistant species such as C. parapsilosis and C. auris, then isolation of an echinocandin-resistant C. auris strain, as reported in other cases5,6. Although the mechanism of resistance in this strain is being studied, echinocandin resistance is usually due to fks1 gene mutations7. Although the patient was treated with anidulafungin, he followed a favourable course, which might have been due to catheter removal, a measure that is always recommended in candidaemia8.

Given that C. auris spreads rapidly among patients, prevention of a C. auris outbreak requires implementation of infection control measures, including: isolation of infected/colonised patients, surveillance cultures to detect colonisations (axillary and inguinal at a minimum), room cleaning upon discharge of a colonised/infected patient and environmental cultures following cleaning8. Compliance with basic hygiene measures on the part of healthcare staff is also essential, especially when handling lines. The usefulness of decolonising patients with antiseptics is debated, although it is normally done with chlorhexidine9. Laboratory identification can be performed using mass spectrometry (matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight [MALDI-TOF]) or molecular methods. When these technique are not available, it recommended that yeasts suspected of being C. auris, such as those identified by biochemical tests as certain phylogenetically related species (e.g. Candida haemulonii or Candida lusitaniae) and those that show resistance to fluconazole, be sent to a reference laboratory10. Given their capacity to acquire resistance, patients being treated for C. auris infections should be monitored, follow-up cultures should be performed on different clinical samples and sensitivity studies should be conducted on all isolates.

C. auris is an emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen that should be incorporated into active surveillance protocols. It is most notable for its high rates of transmission; its multidrug resistance; the difficulties associated with its laboratory identification; and its poor prognosis, as it normally affects seriously ill patients on intensive-care units. Prolonged use of echinocandins, a treatment of choice at present, may give rise to the development of resistant strains, which could further limit treatment options and complicate the management of infections caused by this micro-organism. Once again, it should be noted that managing the focus and changing catheters represent essential measures for achieving clinical success in this context. The importance of managing the spread of C. auris in the hospital environment must also be stressed.

Please cite this article as: Mulet-Bayona JV, Salvador-García C, Tormo-Palop N, Gimeno-Cardona C. Candidemia recurrente y aislamiento de Candida auris resistente a equinocandinas en paciente portador de acceso venoso central de larga duración. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:334–335.