WHO's overall objective against COVID-19 is to control the pandemic situation by reducing the spread and the mortality associated with it. In order to slow down the transmission is the key to actively search for infected patients and subsequently isolate them and track and place their contacts in quarantine.1 The high percentage of asymptomatic patients together with the transmission before the onset of the symptoms make this search particularly complex. However, the screening strategy in the asymptomatic population is still controversial and its efficacy has not been well-established.

The following are the results of a population-based screening for asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infected patients in a high-transmission community (cumulative incidence 14 days 908.05) and a low-traceability (16.55%). Through local social media, all inhabitants (31,068) in the municipality tested (San Andrés del Rabanedo, León, Spain) who did not have any symptoms and had not experienced SARS-CoV-2 infection over the last 3 months were contacted and summoned in a sport center. Nasopharyngeal samples were taken with a swab and tested using the Panbio COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device (Abbott Rapid Diagnostic Jena GmbH) (sensitivity 93.3% and specificity 99.4% according to manufacturer specifications). When invalid results occurred, performing a new test was strongly recommended. All positive cases were invited to allow for a new nasopharyngeal sample on the same day to perform a confirmatory rRT-PCR test. RNA extraction was performed with the Applied Biosystems MagMAX Viral/Pathogen kit using an automated instrument (Thermo Scientific™ KingFisher™) and rRT-PCR was carried out on a QuantStudio 5 system (Applied Biosystems) using a commercial kit (TaqPath COVID-19 CE-IVD RT-PCR Kit, Applied Biosystems) targeting ORF1ab, N and S genes of SARS-CoV-2.

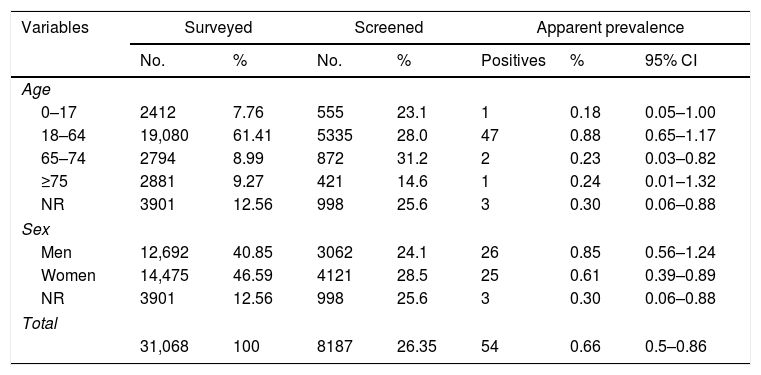

Rapid antigen testing (RAT) was carried out on 8187 people (Table 1). The result was invalid in six samples (none agreed to perform a second test), negative in 8127 and positive in 54 (apparent prevalence 0.66%). No significant differences were observed in the prevalence by sex or age. Of the 54 RAT positive participants, 51 were confirmed using rRT-PCR and three did not agree to have a new sample taken for confirmation. The positive predictive value of the RAT among those who agreed to a confirmatory test (51/51) was 100% as well as the specificity. In the worst scenario, if we assume that the three cases that did not access the rRT-PCR test were not confirmed, the specificity would have been 99.96% (95% CI 99.91–100%).

Population distribution among surveyed, screened and rapid antigen test (RAT) positive individuals and SARS-CoV-2 infection prevalence detected by age and sex.

| Variables | Surveyed | Screened | Apparent prevalence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | Positives | % | 95% CI | |

| Age | |||||||

| 0–17 | 2412 | 7.76 | 555 | 23.1 | 1 | 0.18 | 0.05–1.00 |

| 18–64 | 19,080 | 61.41 | 5335 | 28.0 | 47 | 0.88 | 0.65–1.17 |

| 65–74 | 2794 | 8.99 | 872 | 31.2 | 2 | 0.23 | 0.03–0.82 |

| ≥75 | 2881 | 9.27 | 421 | 14.6 | 1 | 0.24 | 0.01–1.32 |

| NR | 3901 | 12.56 | 998 | 25.6 | 3 | 0.30 | 0.06–0.88 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Men | 12,692 | 40.85 | 3062 | 24.1 | 26 | 0.85 | 0.56–1.24 |

| Women | 14,475 | 46.59 | 4121 | 28.5 | 25 | 0.61 | 0.39–0.89 |

| NR | 3901 | 12.56 | 998 | 25.6 | 3 | 0.30 | 0.06–0.88 |

| Total | |||||||

| 31,068 | 100 | 8187 | 26.35 | 54 | 0.66 | 0.5–0.86 | |

NR, not registered.

In spite of being an area with significant community transmission, the pre-test probability in the investigated area was very low and far below the 5% recommended by WHO to carry out screenings.2 Nevertheless, a 100% specificity such as the one found in this screening program and also previously reported in a situation of low pre-test probability3 or among asymptomatic close contacts4 has resulted in a very acceptable performance as all cases detected were sources of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The average number of threshold cycles (Ct) in the positive cases which underwent rRT-PCR confirmation (considering Cts for N gene) is also worth pointing out. It was 19.0 (SD 3.3) ranging from 13.7 to 29.6, even lower than that reported by other authors in symptomatic patients.3 As previously proposed, samples containing small amounts of virus are most probably classified as negatives using RAT.5 According to this, even in the case of low sensitivity, it could be assumed that false negatives in the RAT are cases with low viral loads and therefore with a limited relevance as sources of infection.6,7

To sum up, we report a high RAT specificity in a mass population screening in real life in a pre-test probability of less than 5%. Although the number of positive samples was limited, our results suggest a high yield of population screening strategies against COVID-19. Moreover, since the screening was organized by the Primary Care Services, all the isolating, care and tracing activities for cases and close contacts was interconnected.8,9 Furthermore, as stated by Mina et al., it is not only the internal validity of a single diagnostic test which should be assessed10; the context of its use and the assessment within a swiss cheese strategy should also be taken into account when setting pre-test probabilities and rethinking the 5% as being a turning point to implement population screening strategies in asymptomatic people.

We would like to thank Lorena Álvarez-González and M. Rosario Esquivel from Regional Laboratory for Animal Health (Junta de Castilla y León) for performing RT-qPCR analysis, Ana Carvajal from University of León for assistance in the research and comments in the manuscript and all those who helped in the organization of the population survey and particularly the teams collecting the samples and the SACYL Technical Director for Emergencies and Primary Care. The research was funded by SACYL projects.