Strongyloides stercoralis is an intestinal nematode endemic in tropical areas with high public health impact.1–3 In Europe, sporadic cases of local infection have been reported in countries like Spain.4,5 Exposure to contaminated soils with larvae leads to its penetration into the human skin and venous system.2 It is known to cause a persistent autoinfection in the host, regulated by the Th2 immune response, mediated by interleukins and IgE, which confers protection against hyperinfection.5 Severe strongyloidiasis cases with autoinfection occur when immunity is impaired with consequent increase of larvae burden.1 Consequently the parasites cross the intestinal wall, causing a hyperinfection syndrome (HIS) or disseminated strongyloidiasis with high mortality rate.6 Carriage of Gram negative bacteria through the intestine along with the larvae or through bowel ulcers is a frequent complication, with consequent septic shock and meningitis.7,8

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1), a retrovirus with clusters of high endemicity around the world,7–9 and strongyloidiasis have been associated.7,8 Infection of T cells lymphocytes leads to an altered humoral immunity response with decreased immunoglobulin secretion.6,7 Other HTLV-1-associated diseases such as lymphoproliferative, autoimmune disorders T-cell leukemia, tropical spastic paraparesis and uveitis, and opportunistic infections8 have been described.

It is important to recognize the risk of strongyloidiasis and HTLV-1 co-infection among the immigrant population1,10 in order to prevent severe complications.

Clinical caseA 53-year-old Brazilian man, living in Portugal for 15 years, with previous history of bacterial meningitis (six months before) without microbiological identification, treated with ampicillin, ceftriaxone, vancomycin and corticosteroids.

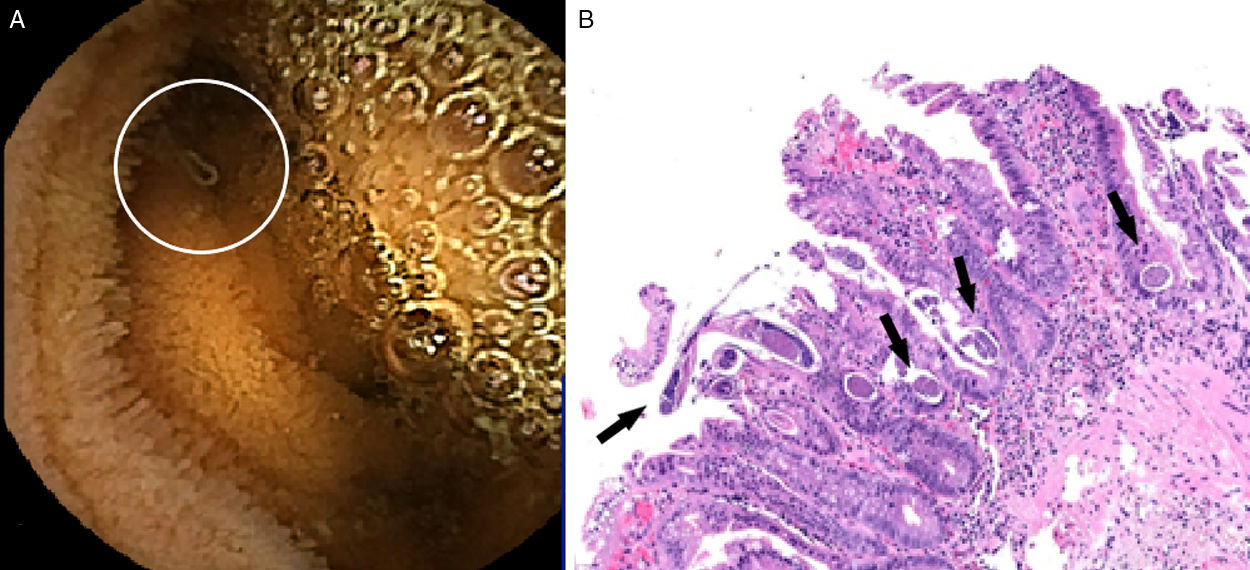

The patient was admitted with the hypothesis of a bacterial meningitis (CSF>1000 polymorphonuclears, 413mg/dL proteins and hypoglycorrhachia 4mg/dL). Antibiotherapy with ampicillin plus ceftriaxone and dexamethasone (10mg every 6h) were started with initial clinical improvement. Gram stain and cultures were negative. After 14 days of admission fever, headache and neck stiffness were noticed with high CSF polymorphonuclears count and hypoglycorrhachia. Assuming a nosocomial meningitis, meropenem and vancomycin were initiated. After Enterococcus faecium isolation in the CSF, meropenem was suspended. Considering the anemia and recurrent meningitis, further investigation was done: negative HIV screening, CD4 T cell count 324cells/mm3 (38%) with lymphocytes 840cells/mm3, positive HTLV-1 serology, negative neoplastic screening. Myelogram showed increased eosinophils (14%) with peripheral eosinophils 270cells/mm3. Small bowel enteroscopy showed jejunum and duodenum segmentary changes with scalloping areas (Fig. 1A). The biopsy revealed an infectious enteritis with several eggs and larvae suggestive of S. stercoralis (Fig. 1B). Stool culture was negative. Stool examination identified rare larvae of S. stercolaris and treatment with albendazole for 10 days was prescribed, followed by another cycle one week after, while waiting for evermectine pharmacy approval. Strongyloides serology was not available.

DiscussionThe presented case concerns a man with recurrent bacterial meningitis episodes without any apparent immunosuppression. Investigation revealed strongyloidiasis and HTLV-1 infection.

S. stercoralis is endemic in Brazil, where the patient was born; nevertheless is frequently neglected in industrialized countries, leading to recurrent and severe Gram negative bacterial infections.6

Epidemiological European studies about HTVL-1 are scarce, reporting infection mostly in blood donors and pregnant women, as they are mostly tested. In Portugal HTLV-1 seropositivity is related to African or South American migrants.9 There is no specific therapy or chemoprophylaxis for HTLV-1; prevention and counseling about transmition routes have been the base the past years.10

A correlation between HTLV-1 and strongyloidiasis has been shown, with a high percentage of S. stercoralis carriers also infected with HTLV-1. Studies in São Paulo demonstrated an immunological impairment in co-infected individuals with more severe HIS cases.7,8 This could be explained by the fact that by infecting T cells lymphocytes, HTLV-1 alters the humoral immunity with an increase of Th1-type (INF-γ and TNF-α) and decrease of Th2-type (IL-4 and IL-10) responses. A decreased IgE secretion, required to the parasitic infection control is observed,6,7,10 contributing to severe helminthic infections.

S. stercoralis, when associated with immunosuppression, has the ability of acting as an opportunistic agent. Severe strongyloidiasis cases associated to short courses of corticotherapy have been reported.1,3

Our patient, presented a strongyloidiasis and HTLV-1 infection with a probable impaired Th2 response, that together could justify the recurrent meningitis episodes. Therapy with dexametasone during admission was a major trigger to larvae burden increase and to a nosocomial meningitis episode.

This case highlights the aspects of two infectious diseases mostly neglected in developed countries and how they can influence the development of a life-threatening disease.

Although we have been observing an increased knowledge about these pathogens, routine screening guidelines are not established. Imunossupressed patients who present a high risk of exposure to S. stercoralis (who have visited or native from endemic areas) should be screened for strongyloidiasis. Individuals starting immunussupressive drugs or chemotherapy are at risk and eosinophil levels, stool examination and serology should be done. Risk categories should be established and European guidelines created due to recent incidence increase in Europe, mostly due to migration. Migrants at risk with previous hyperinfection syndrome should be investigated for immunosuppressive conditions, including HTLV-1.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest and did not receive any financial support. All authors contributed equally to this article. The authors followed their institutions’ protocols to access patient's data, with the unique purpose of scientific investigation and disclosure. All necessary ethical approval and consents were followed.

The authors would like to thank all medical doctors from the Infectious Disease Department for the fruitful discussion concerning this case investigation, Dr. Narcisa Fatela and Dr. Carolina Simões from the Gastroenterology Department who helped us reviewing all gastric exam images to achieve the final diagnosis.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Catarina Quadros and Dr. Emília Vitorino from the Department of Pathology, whose work was essential to achieve the anatomopathological diagnosis.