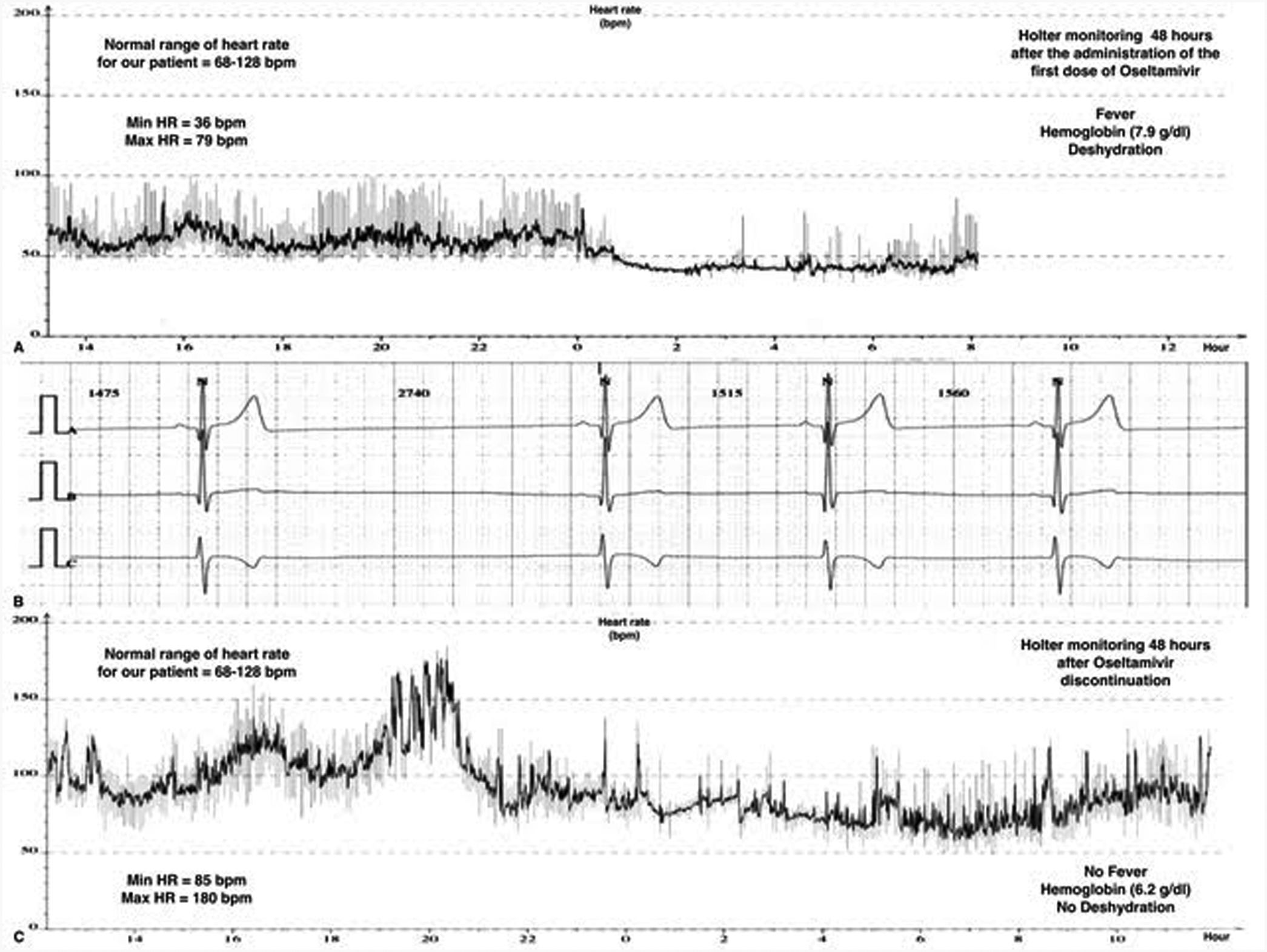

Children constitute a high-risk population for the development of severe influenza regarding adult population. Current recommendations state that antiviral treatment should be provided to all children hospitalized with influenza or underlying medical conditions or those suffering from a severe illness.1 Oseltamivir, a neuraminidase inhibitor (NI), represents the most widely used antiviral in children with influenza viral infection. We report a 10-year-old previously healthy female admitted to our PICU due to an acute kidney injury (AKI) (creatinine clearance <30ml/min/1.73m2), anemia (7.9g/dl) with schistocytosis of 3.5% and thrombocytopenia (29,000/mm3). She was conscious and did not require respiratory or hemodynamical support (SpO2 100%, blood pressure 107/68mmHg and heart rate (HR) 110bpm). She was diagnosed as hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), and supportive treatment with intravenous fluid therapy, blood products, omeprazole and acetaminophen was started. The patient presented flu-like symptoms from the previous 48h, and in the etiological work-up study for HUS, a FilmArray Respiratory Panel detected H1N1 Influenza A as the trigger agent. We considered this clinical picture as a severe manifestation of the influenza virus infection, so treatment with oral Oseltamivir 30mg od. (adjusted for AKI) was initiated. Twelve hours after the first dose we noticed a severe bradycardia on the cardiac monitor, with HR ranging from 30 to 57bpm with a normal blood pressure (Fig. 1). The patient also started with vomiting but did not presented cardiac complaints. Serial ECG records showed sinus bradycardia and nodal rhythm with maximal HR of 60–70bpm without other ECG abnormalities, including a normal QTc interval (400ms). The 3rd day of treatment, a 24-h-Holter monitoring was performed evidencing a mean HR of 53bpm, maximal 85bpm and minimal 36bpm, with 124 documented episodes of bradycardia regarding her age. Remarkably, the patient still presented severe anemia (hemoglobin of 6.2g/dl), fever and clinical signs of dehydration at the time of this Holter monitoring. Cardiac biomarkers (hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP), thyroid function, chest X-ray and echocardiogram resulted in normal. Since she did not manifest cardiac symptoms, we decided to complete 5 days with Oseltamivir at same doses. Twenty-four hours after its withdrawal, we noticed a gradual recovery of HR up to normal values for age, that was confirmed with a new Holter monitoring. Oseltamivir seems to be an effective and well-tolerated therapy for acute influenza A and B infection in children. Nausea and vomiting, usually of mild–moderate intensity and short duration, are the most frequent side effects observed in children.2,3 Severe adverse reactions such as neuropsychiatric are less frequent.4 Although infrequent, cardiac adverse effects associated with Oseltamivir have been previously described in both animals and humans. In concrete, the development QTc interval prolongation and bradycardia seems to be closely related to the rapid increase of Oseltamivir carboxylate in plasma concentrations, even at first dose.5 Some facts make it possible for bradycardia to be associated with Oseltamivir in this case. Occasionally, bradyarrhythmias are the prominent feature in influenza infection due to acute myocarditis, that could be misinterpreted as drug-related adverse events.6,7 However, myocarditis and other secondary causes of bradycardia such as medications were ruled out in our patient. Also, there was a reasonable temporal sequence association between Oseltamivir administration and the appearance of bradycardia, which occurred even in the presence of concurrent causes of tachycardia. Finally, based on a Naranjo adverse drug reaction probability scale value of 5–6 points, bradycardia was considered as a probable side effect of Oseltamivir in our patient.8 Due to the increasing use of Oseltamivir in children, pediatricians must be aware of its possible severe adverse effects. This is especially important in those patients with cardiac or renal comorbidities who are indeed more likely to receive this medication. Oseltamivir is exclusively eliminated by renal excretion, and the dose should be adjusted with creatinine clearance <30ml/min/1.73m2. Although there was no hemodynamics repercussion in our healthy patient, bradycardia could be an adverse event with potentially severe consequences in patients with heart diseases. Therefore, we consider that cardiac monitoring should be warranted during Oseltamivir therapy in those high-risk patients.

Cardiac rhythm monitoring of our patient. Panel A is the record of the HR variability during the first Holter performed the third day of treatment with Oseltamivir, showing a severe bradycardia for age. Panel B is a capture of the cardiac monitor of the patient the first day of treatment with Oseltamivir, showing a sinus bradycardia (30–50bpm). Panel C is the record of the HR variability during the Holter performed after 48h of the discontinuation of Oseltamivir, showing a complete recovery of normal HR for age.

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of interestThe authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.