The objective of this study was to analyse the susceptibility to antibiotic of Citrobacter freundii, Klebsiella aerogenes, Enterobacter cloacae, Serratia marcescens, Providencia stuartii and Morganella morganii (CESPM group), detected in urine cultures.

MethodsBetween 2006 and 2016, we analysed CESPM group Enterobacteria isolated from urine cultures from both primary health-care centres and Hospital Virgen de las Nieves (Granada). We studied the susceptibility to aminoglycosides, fosfomycin, nitrofurantoin, quinolones, piperacillin/tazobactam, cefepime, imipenem and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole following CLSI interpretation criteria.

ResultsA total of 736 isolates were studied: 30.57% E. cloacae, 23.50% M. morganii, 20.38% K. aerogenes, 10.32% C. freundii, 8.83% S. marcescens and 6.38% P. stuartii. A significant decrease in the antibiotic susceptibility was observed. Gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, imipenem and cefepime showed susceptibility over 80%.

ConclusionsE. cloacae, M. morganii and K. aerogenes were the most common isolates. Cefepime and imipenem are still a good empiric therapeutic alternative given its activity in vitro.

El objetivo fue la detección en urocultivos de Citrobacter freundii, Klebsiella aerogenes, Enterobacter cloacae, Serratia marcescens, Providencia stuartii y Morganella morganii (grupo CESPM) para el estudio de su perfil de sensibilidad a los antibióticos.

MétodosEntre 2006 y 2016 se analizaron todos los aislados de enterobacterias del grupo CESPM de urocultivos de centros de atención primaria o del complejo hospitalario Virgen de las Nieves (Granada). Se estudió la sensibilidad a aminoglucósidos, fosfomicina, nitrofurantoína, quinolonas, piperacilina/tazobactam, cefepime, imipenem y trimetoprim/sulfametoxazol, según normas del CLSI.

ResultadosSe estudiaron 736 aislamientos (30,57% E. cloacae; 23,50% M. morganii; 20,38% K. aerogenes; 10,32% C. freundii; 8,83% S. marcescens y 6,38% P. stuartii). Se observó una disminución significativa de la sensibilidad. Para gentamicina, ciprofloxacino, imipenem y cefepime presentaron sensibilidad superior al 80%.

ConclusiónE. cloacae, M. morganii y K. aerogenes fueron las especies más frecuentemente aisladas. Cefepime e imipenem siguen siendo una buena alternativa terapéutica empírica por su actividad in vitro.

Antibiotic resistance rates have increased globally in recent years, especially in gram-negative bacilli. The CESPM group (Citrobacter freundii, Klebsiella aerogenes, Enterobacter cloacae, Serratia marcescens, Providencia stuartii and Morganella morganii) refers to enterobacteria that cause 10% of nosocomial and community-acquired urinary tract infections (UTIs). In addition, they have a high resistance profile due to naturally producing inducible chromosomal AmpC beta lactamases.1–3 Urine cultures from our health area in the last year have demonstrated a prevalence of enterobacteria in adults of 15.2% in the community and 12.8% in hospitalized patients and, in children, 8.3% in the community and 11.1% in hospitalized patients. The objective of this work was the detection of these enterobacteria in our environment to study their susceptibility profile over a period of 11 years, which may help establish a more adequate empirical treatment in risk populations.

MethodsA descriptive analysis of the susceptibility profile of isolated CESPM enterobacteria in urine cultures was performed in the Microbiology Laboratory of the Virgen de las Nieves University Hospital in Granada between 2006 and 2016. Urine was obtained from midstream samples or using catheters (permanent catheter or temporary catheterization) of patients in primary care centres and hospitalized patients. Samples were received in sterile containers or in boric acid tubes (Vacutainer, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, USA). They were processed within 24h after receipt or stored at 5–8°C for 24h if not processed immediately. They were seeded semiquantitatively with 1μl calibrated loops (COPA, Brescia, Italy) in CHROMagar Orientation chromogenic medium (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, USA) at 37°C for 18–24h and, in patients with kidney disease, also in Columbia blood agar (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, USA) in a CO2 atmosphere. Those with one or two uropathogen counts above 100,000CFU/ml (10,000 in urine by probing) or one uropathogen between 10,000 and 100,000CFU/ml (1000–10,000 in urine by probing) were considered positive. The MicroScan Walkaway automated system (Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA), interpreted according to CLSI document M100-S26, was used to identify the microorganisms and for the sensitivity study. In all cases where there was resistance to cefoxitin, the production of AmpC was established through the demonstration of synergy with cloxacillin3 and the production of extended spectrum beta lactamase was excluded by testing synergy with clavulanic acid and the production of carbapenemase with the Rapidec® Carba NP colorimetric test (BioMerieux, France) or, failing that, the Hodge test when necessary.

Duplications of results in urine cultures with an interval of less than 21 days were excluded. For the statistical analysis, IBM SPSS Statistics 19 version 1.7 was used (IMB, Chicago, USA). The categorical variables were expressed as distribution of absolute and relative frequencies, while to analyse the evolution in the rates of susceptibility to the different antibiotics over the study period Pearson's χ2 test for trends was used. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant.

The protocol was conducted in accordance with the Health Research and Ethics Committee of the Hospitals and Health Care Districts; it was a non-interventionist study that only included routine procedures. The data were analysed based on an anonymous database, so no additional permissions were required.

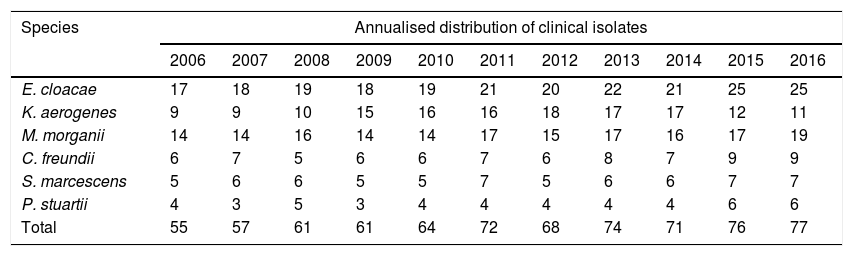

ResultsSome 736 isolates (Table 1) of CESPM microorganisms were studied: 225 (30.57%) E. cloacae; 173 (23.50%) M. morganii; 150 (20.38%) K. aerogenes; 76 (10.32%) C. freundii; 65 (8.83%) S. marcescens and 47 (6.38%) P. stuartii. The mean age was 57.8 years (range 0–95 years), with 416 (56.52%) male and 320 (43.48%) female subjects. The departments of origin were: Emergency 222 (30.16%) isolates; Urology 105 (14.26%); Nephrology 94 (12.77%); Paediatrics 66 (8.96%); Digestive Medicine 52 (7.06%); Internal Medicine 42 (5.70%) and 155 (21.05%) belonging to other departments.

Annualised distribution of urinary clinical isolates of the species E. cloacae, M. morganii, K. aerogenes, C. freundii, S. marcescens and P. stuartii.

| Species | Annualised distribution of clinical isolates | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| E. cloacae | 17 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 19 | 21 | 20 | 22 | 21 | 25 | 25 |

| K. aerogenes | 9 | 9 | 10 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 12 | 11 |

| M. morganii | 14 | 14 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 17 | 15 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 19 |

| C. freundii | 6 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 9 |

| S. marcescens | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| P. stuartii | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Total | 55 | 57 | 61 | 61 | 64 | 72 | 68 | 74 | 71 | 76 | 77 |

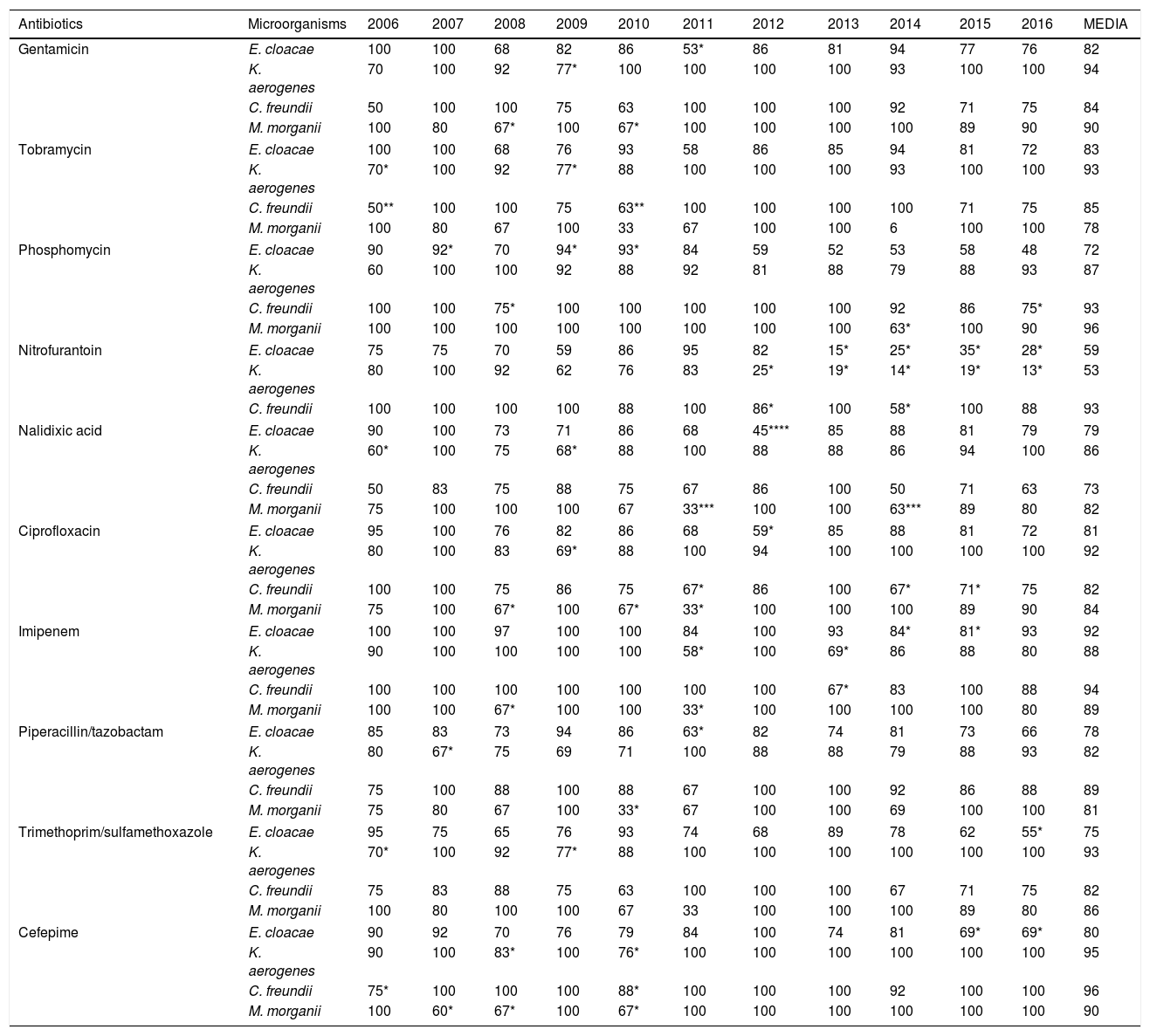

In the susceptibility studies (Table 2) it was observed that, in the four most common microorganisms, this was elevated against aminoglycosides and ciprofloxacin (with exceptions in 2010–2012 for E. cloacae and C. freundii). High susceptibility to imipenem was observed. Cefepime was the antibiotic with the best activity profile for all microorganisms, but presented a significant reduction in susceptibility in 2010. E. cloacae presented a decrease in susceptibility to fosfomycin and was the microorganism with the lowest rate of susceptibility to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and piperacillin/tazobactam. E. cloacae and K. aerogenes saw a decrease in nitrofurantoin susceptibility, with susceptibility rates in 2016 of 28% and 13%, respectively. K. aerogenes was the most susceptible microorganism to nalidixic acid, with an average susceptibility of 86%. The low number of isolates of P. stuartii and S. marcescens meant that it was not possible to show its evolution. In 2015, one isolate of E. cloacae producing a VIM type carbapenemase (in a patient admitted to the Nephrology Department) was identified.

Percentages of antibiotic susceptibility in isolates of microorganisms obtained from urine cultures.

| Antibiotics | Microorganisms | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | MEDIA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gentamicin | E. cloacae | 100 | 100 | 68 | 82 | 86 | 53* | 86 | 81 | 94 | 77 | 76 | 82 |

| K. aerogenes | 70 | 100 | 92 | 77* | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 93 | 100 | 100 | 94 | |

| C. freundii | 50 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 63 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 92 | 71 | 75 | 84 | |

| M. morganii | 100 | 80 | 67* | 100 | 67* | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 89 | 90 | 90 | |

| Tobramycin | E. cloacae | 100 | 100 | 68 | 76 | 93 | 58 | 86 | 85 | 94 | 81 | 72 | 83 |

| K. aerogenes | 70* | 100 | 92 | 77* | 88 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 93 | 100 | 100 | 93 | |

| C. freundii | 50** | 100 | 100 | 75 | 63** | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 71 | 75 | 85 | |

| M. morganii | 100 | 80 | 67 | 100 | 33 | 67 | 100 | 100 | 6 | 100 | 100 | 78 | |

| Phosphomycin | E. cloacae | 90 | 92* | 70 | 94* | 93* | 84 | 59 | 52 | 53 | 58 | 48 | 72 |

| K. aerogenes | 60 | 100 | 100 | 92 | 88 | 92 | 81 | 88 | 79 | 88 | 93 | 87 | |

| C. freundii | 100 | 100 | 75* | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 92 | 86 | 75* | 93 | |

| M. morganii | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 63* | 100 | 90 | 96 | |

| Nitrofurantoin | E. cloacae | 75 | 75 | 70 | 59 | 86 | 95 | 82 | 15* | 25* | 35* | 28* | 59 |

| K. aerogenes | 80 | 100 | 92 | 62 | 76 | 83 | 25* | 19* | 14* | 19* | 13* | 53 | |

| C. freundii | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 88 | 100 | 86* | 100 | 58* | 100 | 88 | 93 | |

| Nalidixic acid | E. cloacae | 90 | 100 | 73 | 71 | 86 | 68 | 45**** | 85 | 88 | 81 | 79 | 79 |

| K. aerogenes | 60* | 100 | 75 | 68* | 88 | 100 | 88 | 88 | 86 | 94 | 100 | 86 | |

| C. freundii | 50 | 83 | 75 | 88 | 75 | 67 | 86 | 100 | 50 | 71 | 63 | 73 | |

| M. morganii | 75 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 67 | 33*** | 100 | 100 | 63*** | 89 | 80 | 82 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | E. cloacae | 95 | 100 | 76 | 82 | 86 | 68 | 59* | 85 | 88 | 81 | 72 | 81 |

| K. aerogenes | 80 | 100 | 83 | 69* | 88 | 100 | 94 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 92 | |

| C. freundii | 100 | 100 | 75 | 86 | 75 | 67* | 86 | 100 | 67* | 71* | 75 | 82 | |

| M. morganii | 75 | 100 | 67* | 100 | 67* | 33* | 100 | 100 | 100 | 89 | 90 | 84 | |

| Imipenem | E. cloacae | 100 | 100 | 97 | 100 | 100 | 84 | 100 | 93 | 84* | 81* | 93 | 92 |

| K. aerogenes | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 58* | 100 | 69* | 86 | 88 | 80 | 88 | |

| C. freundii | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 67* | 83 | 100 | 88 | 94 | |

| M. morganii | 100 | 100 | 67* | 100 | 100 | 33* | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 89 | |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | E. cloacae | 85 | 83 | 73 | 94 | 86 | 63* | 82 | 74 | 81 | 73 | 66 | 78 |

| K. aerogenes | 80 | 67* | 75 | 69 | 71 | 100 | 88 | 88 | 79 | 88 | 93 | 82 | |

| C. freundii | 75 | 100 | 88 | 100 | 88 | 67 | 100 | 100 | 92 | 86 | 88 | 89 | |

| M. morganii | 75 | 80 | 67 | 100 | 33* | 67 | 100 | 100 | 69 | 100 | 100 | 81 | |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | E. cloacae | 95 | 75 | 65 | 76 | 93 | 74 | 68 | 89 | 78 | 62 | 55* | 75 |

| K. aerogenes | 70* | 100 | 92 | 77* | 88 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 93 | |

| C. freundii | 75 | 83 | 88 | 75 | 63 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 67 | 71 | 75 | 82 | |

| M. morganii | 100 | 80 | 100 | 100 | 67 | 33 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 89 | 80 | 86 | |

| Cefepime | E. cloacae | 90 | 92 | 70 | 76 | 79 | 84 | 100 | 74 | 81 | 69* | 69* | 80 |

| K. aerogenes | 90 | 100 | 83* | 100 | 76* | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95 | |

| C. freundii | 75* | 100 | 100 | 100 | 88* | 100 | 100 | 100 | 92 | 100 | 100 | 96 | |

| M. morganii | 100 | 60* | 67* | 100 | 67* | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 90 | |

p values for the decrease in antibiotic susceptibility compared to the mean.

Knowing the susceptibility profiles of the most common uropathogens is of particular importance in order to establish adequate empirical treatments in UTIs, since, being very common, they generate a high health expenditure. CESPM enterobacteria that are resistant to third-generation cephalosporins and do not produce extended-spectrum beta lactamase may produce AmpC, chromosomal or plasmid-mediated beta lactamase4, which needs to be confirmed.

E. cloacae is an especially important pathogen because of its ability to acquire other resistance mechanisms during treatment in addition to those intrinsic to it.5,6 In our work, the lowest susceptibility percentages for most of the antibiotics studied is presented. Cefepime is a fourth generation cephalosporin that weakly induces AmpC betalactamases, as it penetrates rapidly through the gram-negative outer membrane7; therefore, it is considered an alternative to carbapenemes against AmpC microorganisms.7 However, it was not very useful against E. cloacae.

The current scenario has favoured the re-emergent use of traditional antibiotics, such as fosfomycin, whose resistance rates have traditionally been low.8,9 Nitrofurantoin has been considered an excellent therapeutic option for UTI in southern European countries,10 but it reaches only low concentration levels in parenchyma.11 In our study, the significant reduction in susceptibility to these has been building since 2012, coinciding with the publication of UTI treatment guidelines that recommended their use.12 Considering the susceptibility in Enterobacter spp., we can empirically determine that nitrofurantoin is not useful. Aminoglycosides are not usually recommended in uncomplicated UTIs since they have some toxicity and their administration is parenteral. If we consider their use in hospital settings, there are authors who claim that gentamicin is a good alternative to carbapenemes,13 as in our series. Fluoroquinolones are widely used in UTIs due to their broad spectrum, excellent oral bioavailability, good tolerance and postantibiotic effect, but due to their frequent use there has been a marked decrease in susceptibility in enterobacteria.14,15 In our study, we observed how the reduction in susceptibility to ciprofloxacin was growing, which explains why it is the main resistance in beta lactamase producing bacteria, whose coding shares the same genetic elements.

Carbapenemes are the first-line option against AmpC beta lactamases, although in our series we observed a drop in susceptibility to imipenem in the four species between 2013 and 2015, which we could relate to their possible excessive use. For this, cefepime could be an alternative. Imipenem was the drug of choice for the years in which our laboratory only received hospital samples. This phenomenon would explain the decrease in susceptibility for all antibiotics studied, since the bacteria that cause nosocomial UTI have a more resistant profile.

Although in this work targeted treatment with the alternatives cefepime and imipenem is considered as a conclusion, there is a high rate of susceptibility to other antimicrobials and, therefore, any of them may be the drug of choice depending on the patient's clinical situation. If we were talking about empirical treatment, given the low prevalence of UTIs by these microorganisms, the approach would be different. Antibiotics that retain a susceptibility greater than 80% for all species and that, therefore, would be a good alternative to carbapenemes as an empirical treatment, are gentamicin and ciprofloxacin, despite studies concerning the latter as the most common co-resistance in beta lactamase producing bacteria.

The main limitations of this retrospective study are the impossibility of establishing whether the episodes of UTI were complicated or not and whether a previous antibiotic therapy had been used. Therefore, there may be an overestimation of the resistance of the uropathogens studied. In addition, the type of patients varied throughout the study, which may explain the fluctuations. Finally, enterobacteria with AmpC expressed at a low level, such as Escherichia coli were not included, nor has the presence of acquired AmpC beta lactamases in the isolates studied been reported.

In conclusion, the species E. cloacae, M. morganii and K. aerogenes were the enterobacteria with natural inducible chromosomal AmpC beta lactamases most frequently isolated in urine culture, in which the resistance to several groups of antibiotics was common. Cefepime remains a therapeutic alternative to carbapenemes due to its in vitro activity.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Jiménez-Guerra G, Borrego-Jiménez J, Gutiérrez-Soto B, Expósito-Ruiz M, Navarro-Marí JM, Gutiérrez-Fernández J. Evolución de la sensibilidad a los antibióticos de Enterobacter cloacae, Morganella morganii, Klebsiella aerogenes y Citrobacter freundii causantes de infecciones del tracto urinario: un estudio de vigilancia epidemiológica de 11 años. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2020;38:166–169.