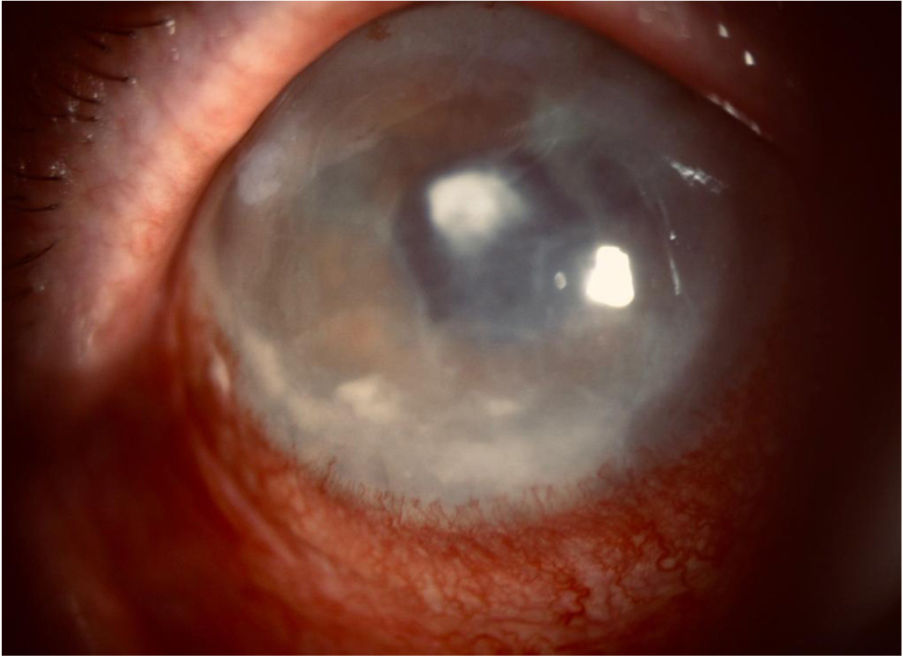

This was an 87-year-old male with type 2 diabetes who had had bilateral cataract surgery at the age of 78. He presented with pseudophakic bullous keratopathy and recurrent corneal ulcers in his right eye. Four months earlier, he had had an amniotic membrane transplant with therapeutic contact lens placement, and been prescribed anti-oedema and cycloplegic eye drops, one drop/8h, artificial tears as required and tobramycin eye drops, one drop/day. The patient consulted with severe stabbing pain in his right eye. Examination revealed normal intraocular pressure, conjunctival hyperaemia, corneal opacity and mild eyelid oedema. Biomicroscopy showed a central corneal abscess of 1.4mm in diameter, hypopyon, severe hyperaemia and corneal oedema. As infectious keratitis was suspected, tobramycin was replaced by fortified vancomycin and ceftazidime eye drops. Two days later, a greater inflammatory reaction, increased turbidity in the anterior chamber and slightly superior hypopyon were observed (Fig. 1). A sample was taken for microbiological culture by scraping the edges and base of the abscess with a scalpel blade.

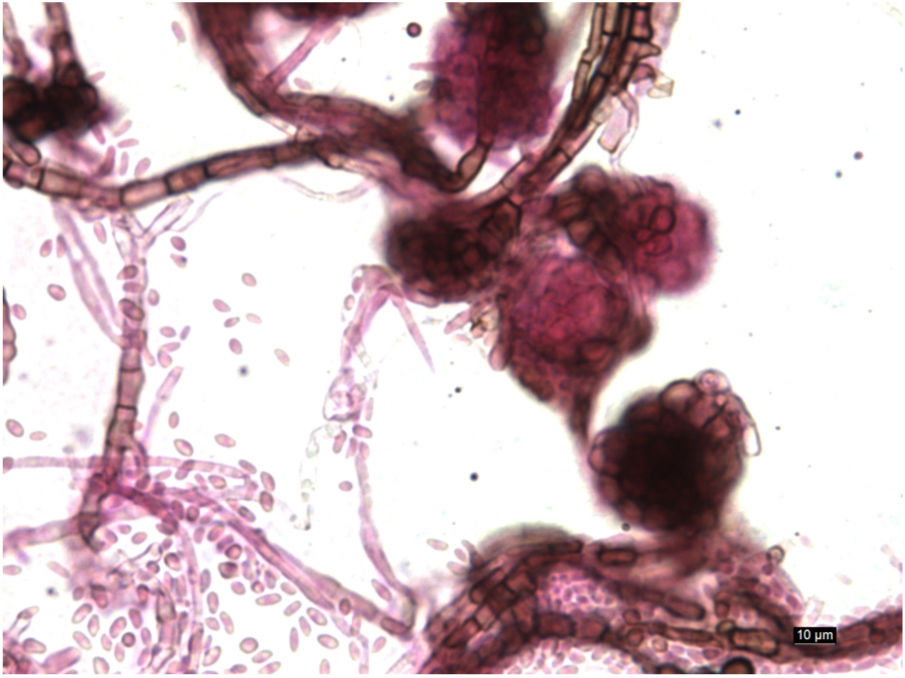

Clinical courseAfter 72h of incubation, the bacteriological culture was negative. In Sabouraud agar at 30°C, cottony, cream-coloured colonies grew, darkening to dark brown after several weeks. Microscopic observation with lacto-fuchsin showed thin septate hyphae with intercalary chlamydospores and pycnidia containing conidia (Fig. 2).

Mycotic keratitis was diagnosed and intrastromal and intracameral voriconazole (50μg/0.1ml) applied, with 200mg/12h voriconazole also prescribed orally and one drop/h topically. We began to see clinical improvement, with disappearance of the hypopyon four days later and reduction of the abscess and perilesional infiltrate after two weeks. Oral voriconazole was continued for two months and topical voriconazole for a further month, and by three months the infection was completely resolved.

The strain was sent to the Centro Nacional de Microbiología (CNM) [Spanish Centre for Microbiology], where Didymella glomerata (formerly Phoma glomerata) was identified by sequencing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region. The sequences were analysed (SeqMan Pro, Lasergene) and compared with databases (GenBank®, MycoBank and CNM). The antifungal activity testing following the EUCAST 9.3 protocol for filamentous fungi showed MIC (μg/ml) of 0.007 to anidulafungin, 0.06 to itraconazole, isavuconazole and micafungin, 0.03 to posaconazole, 0.12 to voriconazole and 0.25 to amphotericin B, terbinafine and caspofungin.

CommentsFungal keratitis is rare in temperate climates, accounting for less than 10 % of keratitis cases.1 The main aetiological agents belong to the genera Fusarium, Aspergillus, Curvularia and Candida.1,2

The species of the genus Phoma are ubiquitous dematiaceous fungi, normally present in plants, soil, water and organic matter. They are common phytopathogens, but only certain species have been associated with animal and human disease.3 There are very few publications on infection in humans, and what there is mainly describes subcutaneous mycoses3,4 and, to a lesser extent, eye infections.5–7

Eye trauma,5,8 contact lenses6,7 and ocular surface disease are risk factors for fungal keratitis.2 It is also associated with bullous keratopathy, diabetes, eye surgery and prolonged corticosteroid therapy or antibiotics.1 In our case, the patient had diabetes and bullous keratopathy, in addition to amniotic membrane transplantation and therapeutic contact lens. The bullous keratopathy was probably the main reason for acquiring the infection, as the rupture of corneal bullae would facilitate the access of microorganisms.

The positive corneal scraping mycological culture and the rapid response to treatment indicate that the sample was representative of the infectious process, negating the need for biopsy.1

Voriconazole has excellent ocular penetration and good activity against filamentous fungi which normally cause keratitis.2,9 which was why it was chosen in our case. There are no breakpoints for the clinical categories of Phoma spp. to antifungals as they are not common human pathogens, and nor is the inoculum for antifungal activity testing standardised. However, we decided to continue voriconazole due to its low MIC and the favourable progress the patient was making. The resolution of the infection confirms the correct choice of antifungal. Moreover, the clinical improvement after intrastromal and intracameral application demonstrates the suitability of this route of administration.8 Plasma voriconazole levels were not monitored due to good treatment response and absence of toxicity and adverse effects.10

Clinical suspicion of fungal keratitis in patients with risk factors facilitates the early establishment of adequate treatment, which improves the prognosis. As Phoma spp. is rarely isolated in clinical practice, we highlight the utility of molecular diagnosis for identification.4–7

FundingThe authors declare that they have not received any funding for this article.

Please cite this article as: Gaona-Álvarez C, González-Velasco C, Morais-Foruria F, Alastruey-Izquierdo A. Queratitis de etiología inusual en paciente con queratopatía bullosa. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2020;38:84–85.