Polyneuropathy and myopathy, grouped under the term “intensive care unit-acquired weakness” (ICUAW), are neuromuscular pathologies to which patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) are susceptible. They are multifactorial pathologies, prolonged connection to a ventilator is one of the most common. The objective of this review was to identify the efficacy of different rehabilitative treatments in patients with ICUAW, and the relationship between ICUAW and a series of indicators.

MethodsA systematic review of the primary studies selected from the Medline, Scielo, Web of Science, Cochrane, Cuiden and Science Direct databases was carried out, following the guidelines of the PRISMA statement, by which the search protocol was established.

Results and conclusionsOf 161 articles, only 10 were selected to be part of this review, in which a total of 717 patients admitted to the ICU were studied. A statistically significant relationship was observed between ICUAW and failure in ventilator disconnection, mortality, increase in ICU stay and the time that the patients required mechanical ventilation. Moreover, all this improved in this type of patients with the application of a rehabilitation therapy. The use of corticosteroids, was not shown to be related to neuromuscular alteration.

La polineuropatía y la miopatía, agrupadas bajo el término «polineuromiopatía del paciente crítico» (PNMPC), son enfermedades neuromusculares que los pacientes de la unidad de cuidados intensivos (UCI) son susceptibles de presentar. Son enfermedades multifactoriales: la conexión prolongada al ventilador es uno de los factores más comunes. El objetivo de esta revisión ha sido identificar la eficacia de diferentes tratamientos rehabilitadores en pacientes con PNMPC y la relación entre esta y una serie de indicadores hospitalarios.

MetodologíaSe ha realizado una revisión sistemática de los estudios primarios seleccionados de las bases de datos Medline, Scielo, Web of Science, Cochrane, Cuiden y Science Direct, siguiendo las directrices de la declaración PRISMA, a través de la cual se estableció el protocolo de búsqueda.

Resultados y conclusionesDe 161 artículos, solo 10 fueron seleccionados para formar parte de esta revisión, en la cual se estudiaron un total de 717 pacientes ingresados en la UCI. Se ha observado una relación estadísticamente significativa entre la PNMPC y el fallo en la desconexión del ventilador, la mortalidad, el aumento de estancia en UCI y del tiempo que los pacientes necesitan ventilación mecánica. Además, todo ello mejora en este tipo de pacientes con la aplicación de alguna terapia rehabilitadora. El uso de corticoides, por el contrario, no ha demostrado tener relación con la alteración neuromuscular.

Several different advances in the treatments applied to patients who have been admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) has led to an improvement in the prognosis and survival of these patients. However, neuromuscular diseases may present which the patients did not previously suffer from. These diseases are directly related to prolonged stays in the ICU, the severity of the illnesses for which the patients were admitted into hospital and the treatment used to combat them.1

A series of neurological problems are included in this group of diseases, and these affect the peripheral nerve system. The most common and well known of these is the critically ill patient polyneuropathy (CPP) which may present in between 50% and 80% of these patients.2 Even so, doubts exist regarding their aetiology, pathology, prognosis and treatment.3 This alteration leads to a degeneration of the myelin sheaths which may delay nerve signal flow. If this occurs in the axon or the complete neuron the nerve may stop functioning. All of this may affect the striated muscle fibres due to the denervation they suffer and these may lead to the onset of symptoms and signs in the patient: a reduction in sensitivity, general muscular weakness, difficulty swallowing or breathing, muscular spasms, and a reduction in reflexes and neuralgias. The facial muscles usually remain intact, although they may also be affected.4

At present, several authors use the concept “critically ill polyneuropathy and myopathy patient”, which covers the terms critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP) and critical illness myopathy (CIM), another type of condition of the peripheral neuromuscular system where atrophy of muscular fibres occur and there is a reduction in the potential for action. This is due to the difficulty in carrying out neurological examinations in patients who have been admitted to the ICU, to the similarities between the clinical signs and the frequency with which they simultaneously present.3 In this systematic review, we use the term “critical illness polyneuromyopathy” (CIPNM). This illness has a multifactorial aetiology: the most common factors associated with it are a prolonged stay in ICU, sepsis, multi organ failure and connection to the ventilator, which lead to failures in disconnection, an increase in the treatment time with mechanical ventilation (MV), changes to the respiratory musculature and an increase in mortality after 30 days. Other factors such as treatment with neuromuscular blockers, corticosteroids, sedatives or muscle relaxants continue under debate. However, blood glucose control and early mobility therapy have proven to drastically reduce this neuropathy.4,5

During the acute phase of the illness, for which these patients are admitted into the ICU, the signs of CIPNM may be concealed with the use of muscle relaxants and sedatives. Generally, the healthcare personnel who work with critically ill patients acknowledge that this illness is a major cause of muscle weakness which presents due to the impossibility of disconnecting them from the ventilator once the critical condition for which they were admitted to the ICU has been resolved. Up to 62% of these patients show signs of sufficiently significant neuromuscular dysfunction to explain the persistent respiratory failure of these patients, which could even begin at after 18h from the start of MV.4,6

In these cases scales of measurement are highly useful as they help us to make a definitive diagnosis based on the patient's clinical condition. The assessment method regularly used in clinical practice is the modified scale of muscle strength published by the Medical Research Council (MRC). This tool enables us to assess the function of muscles with a grading from 0 to 5, where 0 would be total degeneration, where no active contraction was detected on palpation, whilst patients with grade 5 would maintain normal strength and display maximum resistance to the healthcare staff. Over and above this, other tools of measurement exist which are less specific, but which also offer us information as to the severity of the critically ill patient. One of these is the APACHE II scale or the Barthel index.6 Nerve biopsy is not essential for diagnosis of this condition, but the need for imaging or electrophysiological studies should be recognised (electromyograms and sensory and motor nerve function conduction) as further studies in the neurological examination when appropriate: they are useful in pinpointing whether the problem is of central nervous origin (intracraneal or medullary) or peripheral (neuromuscular).4,7

It is necessary to ensure that this weakness did not exist prior to admittance and to rule out trauma, Guillain-Barré syndrome, muscular dystrophy, myesthenia gravis, botulism or Eaton-Lambert syndrome, among others, to be able to specify the factors connected with the problem and to prescribe correct, accurate treatment. Moreover, it is essential that the severity of the condition be recognised, given that in mild cases rehabilitation could be carried out in weeks. As the condition worsens, the functional prognosis becomes poorer and a major reduction in movement may occur together with a fall in quality of life after 2 years.8

Several clinical trials suggest the inclusion of nutritional and antioxidant supplements, activated protein C and immunogobulins, but none have proven to be effective. The only treatment where a reduction in complications has been observed is prevention, with the emphasis in maintaining a strict control of blood glucose levels through insulin treatment, early management of sepsis, reduction in time the patient is connected to a ventilator, with early spontaneous respiratory testing, the prevention of complications and early rehabilitation.5,6

The main purpose of this systematic review was to describe the efficacy of rehabilitation treatments (occupational and physical therapy; muscular electro stimulation; euglycaemic control and early mobilisation) in patients with CIPNM. Our secondary objective was to describe the association between this neuromuscular change and the length of stay in the ICU, the connection time to the ventilator and the rate of failure in disconnection, consumption of corticosteroids and mortality.

Material and methodA systematic review of primary studies was undertaken in the data bases of Medline, Scielo, Web of Science, Cochrane, Cuiden and Science Direct, under the guidelines of the PRISMA declaration through which the search protocol was established. The PICO question which defined the issue and limited the search was: “in patients with PNMC who are in the Intensive Care Unit, is the application of a rehabilitation treatment (occupational and physical therapy, muscular electro stimulation, euglycaemic control and early mobilisation) effective or not, in terms of length of stay in the ICU, time of connection and rate of failure in disconnection to the ventilator, the consumption of corticosteroids and mortality?”

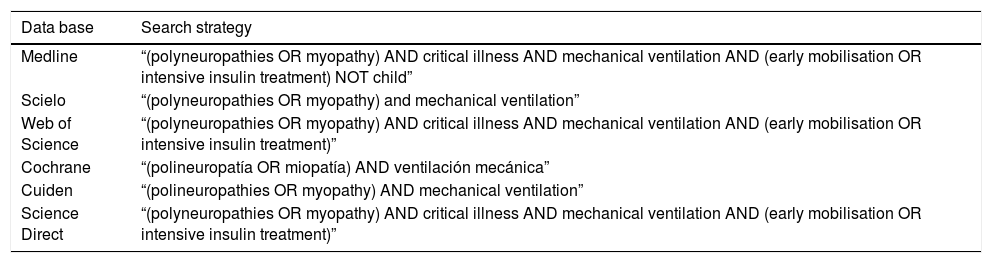

Searches adapted to the different data bases used were made, using the descriptors “polyneuropathies/polineuropatías”, “myopathy/miopatía”, “critical illness”, “mechanical ventilation”, “early mobilization” and “intensive insulin treatment” combining them with one another with the Boolean operator “and”, all those described in the DeCS thesaurus, excluding the paediatric and neonatal populaiton study (“not child”). The different advanced search strategies used in each data base (Table 1) are listed below.

Search strategies used.

| Data base | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| Medline | “(polyneuropathies OR myopathy) AND critical illness AND mechanical ventilation AND (early mobilisation OR intensive insulin treatment) NOT child” |

| Scielo | “(polyneuropathies OR myopathy) and mechanical ventilation” |

| Web of Science | “(polyneuropathies OR myopathy) AND critical illness AND mechanical ventilation AND (early mobilisation OR intensive insulin treatment)” |

| Cochrane | “(polineuropatía OR miopatía) AND ventilación mecánica” |

| Cuiden | “(polineuropathies OR myopathy) AND mechanical ventilation” |

| Science Direct | “(polyneuropathies OR myopathy) AND critical illness AND mechanical ventilation AND (early mobilisation OR intensive insulin treatment)” |

Inclusion criteria: primary studies published from 30/04/2009 until the present. Searches were limited to retrospective observational studies, prospective studies or full text clinical trials performed on critically ill patients in the ICU, aged >15 years, with MV and whose outcome variable was the onset of a polyneuromyopathy.

Exclusion criteria: systematic reviews, opinion articles and meta-analysis and studies which had been published in languages other than English, Spanish or Portuguese were excluded.

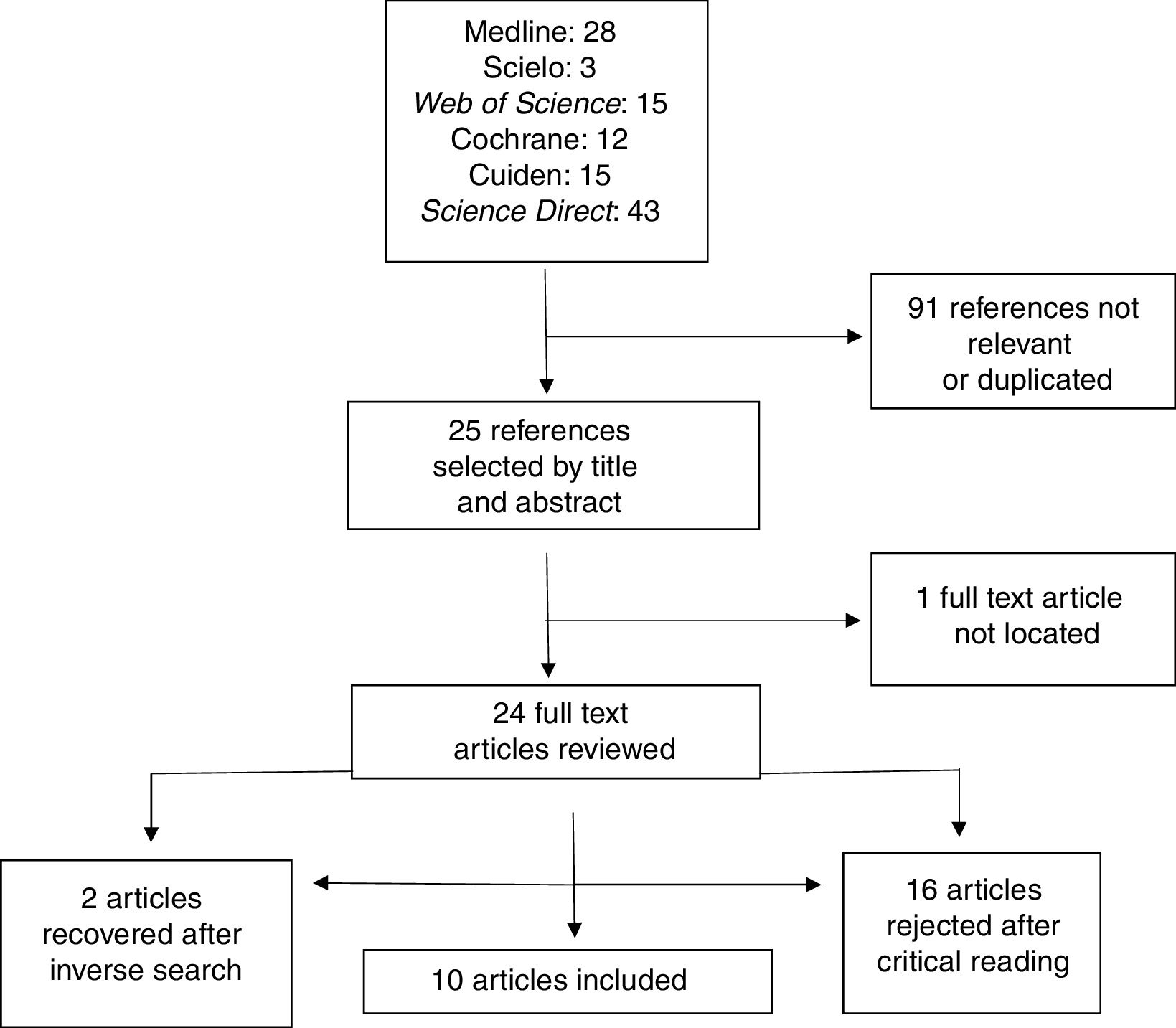

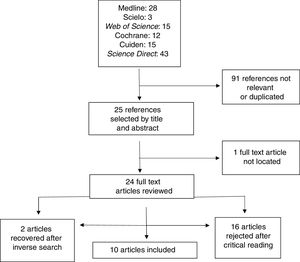

In total, 116 bibliographic references were located in the different electronic data bases: 28 in Medline, 3 in Scielo, 15 in Web of Science, 12 in Cochrane, 15 in Cuiden and 43 in Science Direct. The first selection of articles was made by title and the quality of the abstract. 91 references were rejected because they were not relevant or had been duplicated. Assessment was methodological in the second review, following the CASPe,9 template, in order to assess the possible biases and rule out the references which did not meet the proposed inclusion criteria. We therefore excluded 16 articles after critical reading of them (of these, 13 were systematic reviews) and one which was not available as a full text. Furthermore, 2 articles were recuperated using the inverse search, which allowed us to work with a total of 10 articles (Fig. 1).

All the studies had a good or moderate internal validity. They were classified according toothier levels of evidence (LE) and grades of recommendation (GR) in keeping with the SIGN scale.10 The Mendeley bibliography manager was also used for referencing the bibliography, guided by the Vancouver regulations.

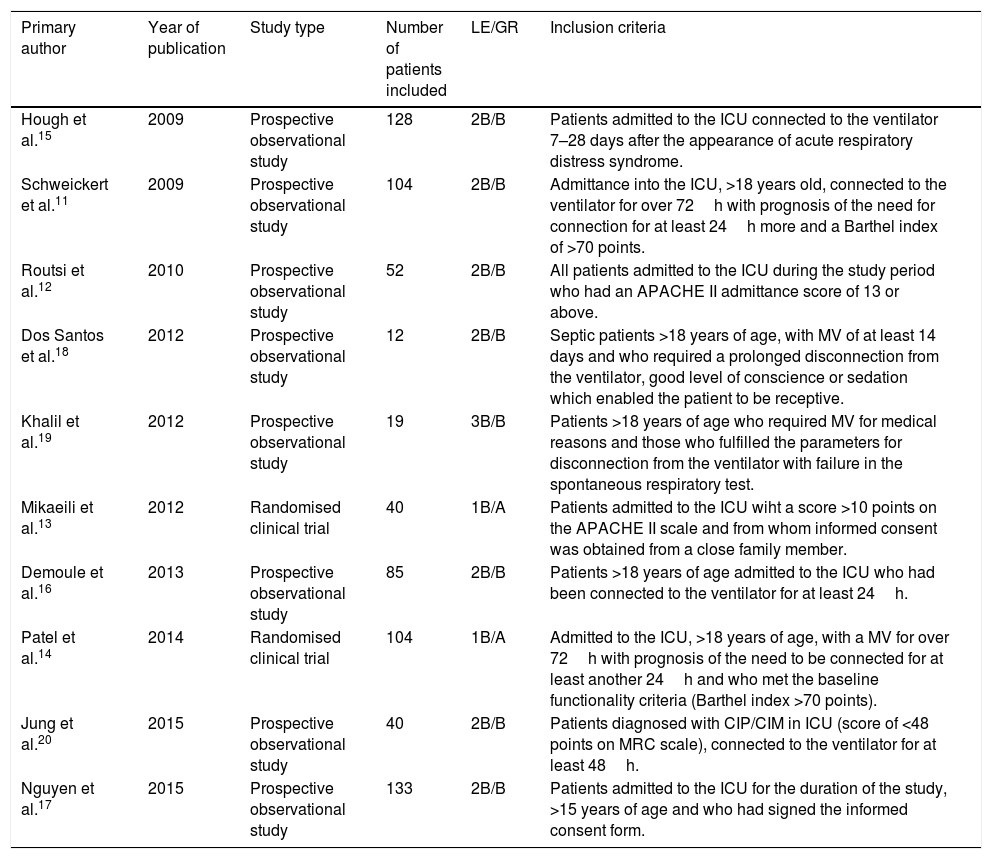

ResultsFinally, the study was conducted with 10 articles: 8 of them were prospective observational studies and 2 were randomised clinical trials, with sample sizes of between 12 and 133 participants (Table 2).

Selected studies and their features.

| Primary author | Year of publication | Study type | Number of patients included | LE/GR | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hough et al.15 | 2009 | Prospective observational study | 128 | 2B/B | Patients admitted to the ICU connected to the ventilator 7–28 days after the appearance of acute respiratory distress syndrome. |

| Schweickert et al.11 | 2009 | Prospective observational study | 104 | 2B/B | Admittance into the ICU, >18 years old, connected to the ventilator for over 72h with prognosis of the need for connection for at least 24h more and a Barthel index of >70 points. |

| Routsi et al.12 | 2010 | Prospective observational study | 52 | 2B/B | All patients admitted to the ICU during the study period who had an APACHE II admittance score of 13 or above. |

| Dos Santos et al.18 | 2012 | Prospective observational study | 12 | 2B/B | Septic patients >18 years of age, with MV of at least 14 days and who required a prolonged disconnection from the ventilator, good level of conscience or sedation which enabled the patient to be receptive. |

| Khalil et al.19 | 2012 | Prospective observational study | 19 | 3B/B | Patients >18 years of age who required MV for medical reasons and those who fulfilled the parameters for disconnection from the ventilator with failure in the spontaneous respiratory test. |

| Mikaeili et al.13 | 2012 | Randomised clinical trial | 40 | 1B/A | Patients admitted to the ICU wiht a score >10 points on the APACHE II scale and from whom informed consent was obtained from a close family member. |

| Demoule et al.16 | 2013 | Prospective observational study | 85 | 2B/B | Patients >18 years of age admitted to the ICU who had been connected to the ventilator for at least 24h. |

| Patel et al.14 | 2014 | Randomised clinical trial | 104 | 1B/A | Admitted to the ICU, >18 years of age, with a MV for over 72h with prognosis of the need to be connected for at least another 24h and who met the baseline functionality criteria (Barthel index >70 points). |

| Jung et al.20 | 2015 | Prospective observational study | 40 | 2B/B | Patients diagnosed with CIP/CIM in ICU (score of <48 points on MRC scale), connected to the ventilator for at least 48h. |

| Nguyen et al.17 | 2015 | Prospective observational study | 133 | 2B/B | Patients admitted to the ICU for the duration of the study, >15 years of age and who had signed the informed consent form. |

GR: grades of recommendation; MRC: Medical Research Council; LE: level of evidence; ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

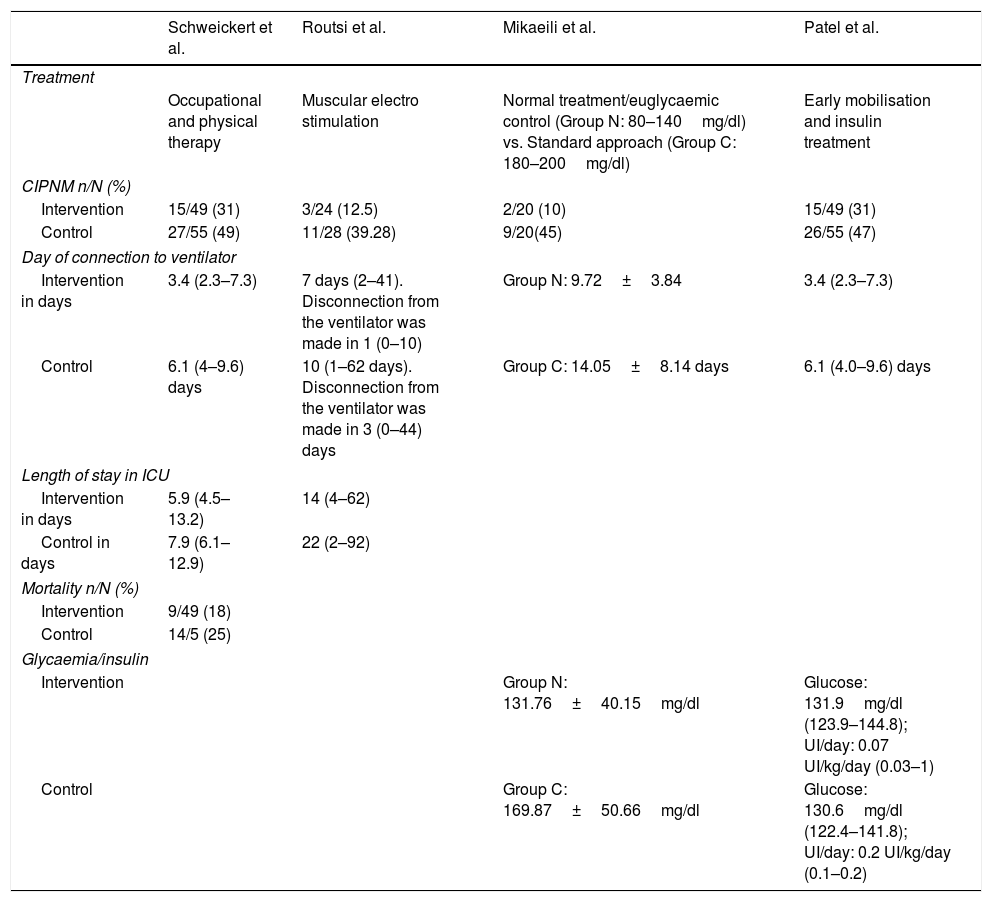

The chosen study methodology was based on analysis of the efficacy of different rehabilitation treatments in patients connected to the ventilator, comparing 2 groups: one who received the treatment and another who did not, and observing the rate of CIPNM in each of them. These results were obtained from 4 articles listed in Table 3.

Results of the different rehabilitation treatments and their association with the different indicators.

| Schweickert et al. | Routsi et al. | Mikaeili et al. | Patel et al. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | ||||

| Occupational and physical therapy | Muscular electro stimulation | Normal treatment/euglycaemic control (Group N: 80–140mg/dl) vs. Standard approach (Group C: 180–200mg/dl) | Early mobilisation and insulin treatment | |

| CIPNM n/N (%) | ||||

| Intervention | 15/49 (31) | 3/24 (12.5) | 2/20 (10) | 15/49 (31) |

| Control | 27/55 (49) | 11/28 (39.28) | 9/20(45) | 26/55 (47) |

| Day of connection to ventilator | ||||

| Intervention in days | 3.4 (2.3–7.3) | 7 days (2–41). Disconnection from the ventilator was made in 1 (0–10) | Group N: 9.72±3.84 | 3.4 (2.3–7.3) |

| Control | 6.1 (4–9.6) days | 10 (1–62 days). Disconnection from the ventilator was made in 3 (0–44) days | Group C: 14.05±8.14 days | 6.1 (4.0–9.6) days |

| Length of stay in ICU | ||||

| Intervention in days | 5.9 (4.5–13.2) | 14 (4–62) | ||

| Control in days | 7.9 (6.1–12.9) | 22 (2–92) | ||

| Mortality n/N (%) | ||||

| Intervention | 9/49 (18) | |||

| Control | 14/5 (25) | |||

| Glycaemia/insulin | ||||

| Intervention | Group N: 131.76±40.15mg/dl | Glucose: 131.9mg/dl (123.9–144.8); UI/day: 0.07 UI/kg/day (0.03–1) | ||

| Control | Group C: 169.87±50.66mg/dl | Glucose: 130.6mg/dl (122.4–141.8); UI/day: 0.2 UI/kg/day (0.1–0.2) | ||

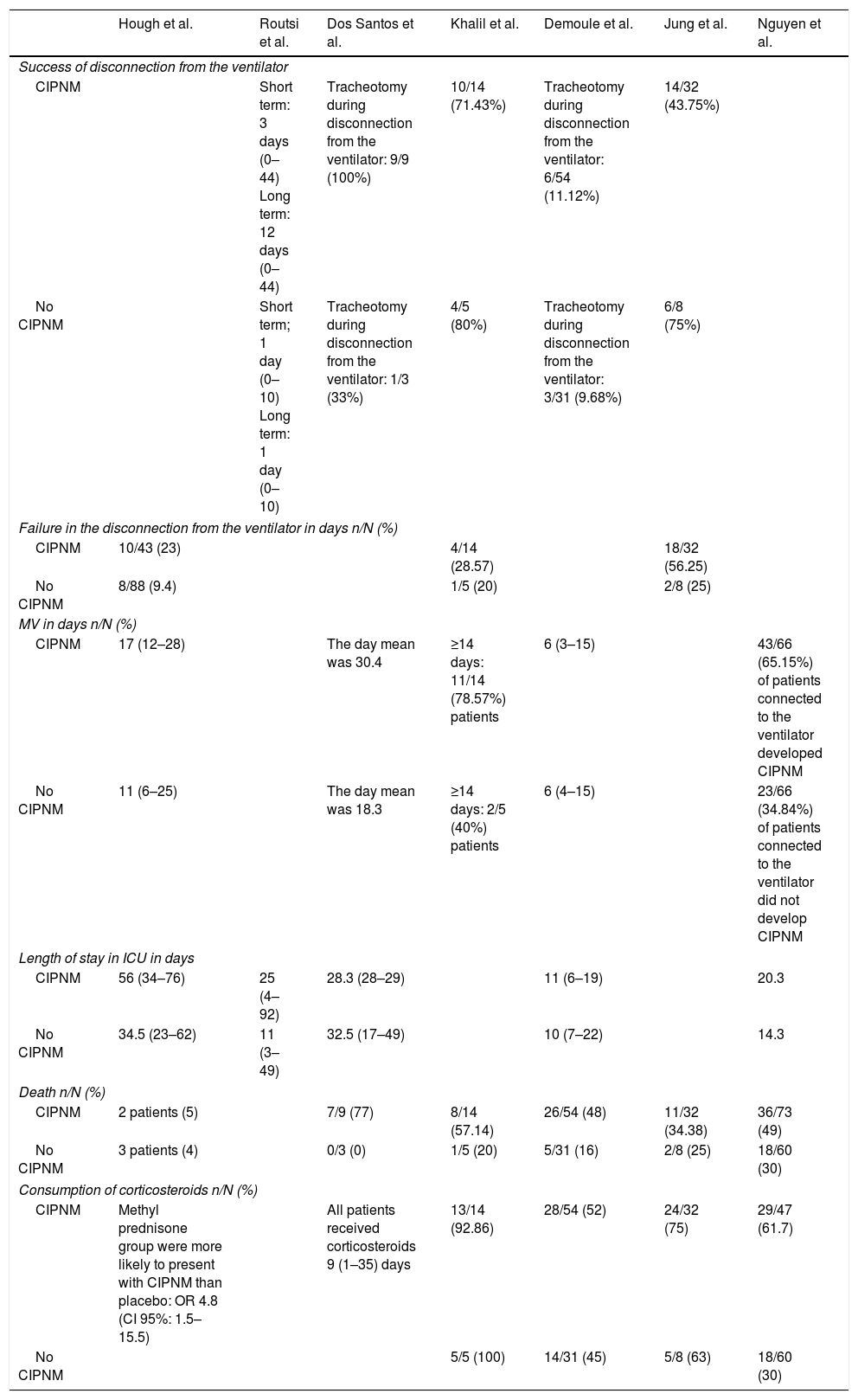

In 7studies the difference between the success or failure of disconnecting the patient from the ventilator was identified, as was the need to receive MV or not, and when it was necessary, its duration, together with the length of stay in the ICU, the consumption of corticosteroids and mortality between a group of patients who had developed CIPNM and those who had not, with subsequent observation of any existing association between them (Table 4).

Association between the onset of CIPNM and the different indicators.

| Hough et al. | Routsi et al. | Dos Santos et al. | Khalil et al. | Demoule et al. | Jung et al. | Nguyen et al. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success of disconnection from the ventilator | |||||||

| CIPNM | Short term: 3 days (0–44) Long term: 12 days (0–44) | Tracheotomy during disconnection from the ventilator: 9/9 (100%) | 10/14 (71.43%) | Tracheotomy during disconnection from the ventilator: 6/54 (11.12%) | 14/32 (43.75%) | ||

| No CIPNM | Short term; 1 day (0–10) Long term: 1 day (0–10) | Tracheotomy during disconnection from the ventilator: 1/3 (33%) | 4/5 (80%) | Tracheotomy during disconnection from the ventilator: 3/31 (9.68%) | 6/8 (75%) | ||

| Failure in the disconnection from the ventilator in days n/N (%) | |||||||

| CIPNM | 10/43 (23) | 4/14 (28.57) | 18/32 (56.25) | ||||

| No CIPNM | 8/88 (9.4) | 1/5 (20) | 2/8 (25) | ||||

| MV in days n/N (%) | |||||||

| CIPNM | 17 (12–28) | The day mean was 30.4 | ≥14 days: 11/14 (78.57%) patients | 6 (3–15) | 43/66 (65.15%) of patients connected to the ventilator developed CIPNM | ||

| No CIPNM | 11 (6–25) | The day mean was 18.3 | ≥14 days: 2/5 (40%) patients | 6 (4–15) | 23/66 (34.84%) of patients connected to the ventilator did not develop CIPNM | ||

| Length of stay in ICU in days | |||||||

| CIPNM | 56 (34–76) | 25 (4–92) | 28.3 (28–29) | 11 (6–19) | 20.3 | ||

| No CIPNM | 34.5 (23–62) | 11 (3–49) | 32.5 (17–49) | 10 (7–22) | 14.3 | ||

| Death n/N (%) | |||||||

| CIPNM | 2 patients (5) | 7/9 (77) | 8/14 (57.14) | 26/54 (48) | 11/32 (34.38) | 36/73 (49) | |

| No CIPNM | 3 patients (4) | 0/3 (0) | 1/5 (20) | 5/31 (16) | 2/8 (25) | 18/60 (30) | |

| Consumption of corticosteroids n/N (%) | |||||||

| CIPNM | Methyl prednisone group were more likely to present with CIPNM than placebo: OR 4.8 (CI 95%: 1.5–15.5) | All patients received corticosteroids 9 (1–35) days | 13/14 (92.86) | 28/54 (52) | 24/32 (75) | 29/47 (61.7) | |

| No CIPNM | 5/5 (100) | 14/31 (45) | 5/8 (63) | 18/60 (30) | |||

For this, as may be observed in Tables 3 and 4, the total results of the study were derived from 2 different but complementary points of view: on the one hand, the factors leading to CIPNM and its association with the different hospital indicators and on the other, the effectiveness of a rehabilitation treatment in developing the illness of not.

Description of the study resultsFour articles11–14 measured the efficacy of rehabilitation treatments in critically ill patients with MV who had been admitted to the ICU. Their objective was to assess what the differences were between the group who had received the treatment and the group which had not. These treatments were: occupational and physical therapy, muscular electro stimulation, euglycaemic control and early mobilisation. In general, all the articles offered results which backed up their execution, since the rate of patients with CIPNM significantly declined, as did time of connection to the ventilator, length of stay in ICU and mortality of those who formed part of the intervention group.

In their trials Mikaeili et al.13 and Patel et al.14 also included the administration of insulin and the measurement of glycaemia as indicators. In the former trial,13 therapy consisted in maintaining blood glucose rates between 80 and 140mg/dl in one of the groups and in the latter trial,14 the authors studied the efficacy of early mobilisation and glycaemia control. In both the rate of CIPNM dropped significantly as did the ventilator connection time.

Those patients who developed CIPNM had a higher mean stay in the ICU, and these differences were statistically significant.12,15–17 However, Santos et al.18 found that the patients who did not develop any neuromuscular change had had a slightly longer stay than those affected by neuropathy, but the association between the two was not significant.

However, it was observed that in patients with CIPNM connection to the ventilator had been higher,15,17–19 with statistically significant differences except in the study of Khalil et al.19 The study conducted by Demoule et al.16 showed that the mean of days in both groups was the same.

With regards to the failure in disconnection from the ventilator, the patients who developed CIPNM were successfully disconnected later, failed in a higher number of occasions, and had further complications.12,15,18–20 These differences were statistically significant in the studies of Hough et al.,15 Routsi et al.12 and Santos et al.18 Also, Santos et al.18 observed that these patients more frequently required tracheotomy compared to those who had not presented with any type of neuromuscular change.

The association between the administration of corticosteroids and the rate of CIPNM in critically ill patients is a subject which remains under debate. The majority of authors 15–17,20 observed a higher incidence of CIPNM in patients who received treatment with corticosteroids, with the exception of Khalil et al,.19 who found there was an inverse relationship. This association was not statistically significant in any of the studies.

Lastly, in all trials included in our study7,15,17–20 a higher rate of mortality may be observed in patients with CIPNM. This was statistically significant in all studies, with the exception of those by Hough et al.15 and Jung et al.20

DiscussionDuring recent decades there has been a notable increase in the number of articles dealing with the association between patients who are in the ICU and CIPNM. As a result of this, the outcome of this study has been compared with those obtained by other authors in their articles and a concordance between them has been obtained.

In their articles Medica et al.,21 McWilliams et al.22 and Needham et al.23 also demonstrated effectiveness in the different rehabilitation treatments in this type of patients.

De Jonghe et al.24 and Busico et al.25 classified CIPNM as a risk factor due to the increase of complications when disconnecting patients from the ventilator and an increase in the time which the patient received MV (p<.05). Others including Garnacho-Montero et al.26 coincided with those of our review since here the author directly related the presence of this change with a longer stay in the ICU and in the hospital. With regard to the administration of corticosteroids, Wilcox et al.27 and Zorowitz et al.28 obtained similar results to those found: patients who had been given corticosteroids had a higher incidence of CIPNM, but the ratio between both indicators was not statistically significant. Lastly Hermans et al.29 found there was an association between an increase in mortality and this illness.

These results have different implications for clinical practice, alerting healthcare professionals in diagnosis and the need for early treatment in this type of patient: apart from reducing the possibility of developing CIPNM, there is a lowering of the need for hospital care and length of hospital stay, which in turn also reduces healthcare costs per patient.

To conclude, it has been demonstrated that rehabilitation treatment (occupational and physical therapy, muscular electro stimulation, euglycaemic control and early mobilisation) improves the general status of this type of patient, reducing the rate of CIPNM, the time of being connected to the ventilator, the length of stay in the ICU and mortality. Furthermore, this neuromuscular change is a common complication of critical illness associated with muscle weakness and all the indicators studied, except for the use of corticosteroids, which has not been demonstrated to be associated with the onset of this change.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez Solana L, Goñi Bilbao I, Ruiz García P, Díaz Agea JL, Leal Costa C. Disfunción neuromuscular adquirida en la unidad de cuidados intensivos. Enferm Intensiva. 2018;29:128–137.