To identify factors associated with in-hospital mortality, to estimate the intubation rate and to describe in-hospital mortality in patients over 65 years old with invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) in the emergency department (ED).

MethodsRetrospective cohort study of patients over 65 years old, who were intubated in an ED of a high complexity hospital between 2016 and 2018. Demographic data, comorbidities, and severity scores on admission were described. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed with logistic regression according to mortality and possible confounders.

ResultsA total of 285 patients with a mean age of 80 years required IMV in the emergency department, for a median of 3 days, and with a mean APACHE II score of 20 points of severity. The IMV rate was .48% (95% CI .43–.54), and 55.44% (158) died. Mortality-associated factors after age and sex adjustment were stroke (OR 2.13; 95% CI 1.21–3.76), chronic kidney failure, (OR 4.,38; 95% CI 1.91–10.04), Charlson index (OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.02−1.38), APACHE II score (OR 1.07; 95% CI 1.02−1.12), and SOFA score (OR 1.14; 95% CI 1.03−1.27).

DiscussionOur IMV rate was lower than that stated by Johnson et al. in the United States in 2018 (.59%). In-hospital mortality in our study exceeded that predicted by the APACHE II score (40%) and SOFA (33%). However it was consistent with that reported by Lieberman et al. in Israel and Esteban et al. in the United States.

ConclusionsAlthough the IMV rate was low in the ED, more than half the patients died during hospitalization. Pre-existing cerebrovascular and renal diseases and high results in the comorbidities index and severity scores on admission were independent factors associated with in-hospital mortality.

Identificar los factores asociados a mortalidad intrahospitalaria, estimar la tasa de intubación y describir la mortalidad intrahospitalaria de mayores de 65 años que requirieron ventilación mecánica invasiva (VMI) en el servicio de urgencias.

MétodosEstudio de cohorte retrospectiva con pacientes mayores de 65 años, intubados en la central de emergencias del adulto entre 2016 y 2018 en un hospital de alta complejidad. Se consignaron datos demográficos, comorbilidades y scores de severidad al ingreso. Se realizaron análisis bivariado y multivariado con regresión logística en relación a mortalidad hospitalaria y posibles confundidores.

ResultadosUn total de 285 pacientes con media de 80 años requirieron VMI en urgencias durante una mediana de 3 días, y con media de 20 puntos de severidad según APACHE II. La tasa de VMI resultó 0,48% (IC95% 0,43−0,54), y 55,44% (158) fallecieron. Los factores asociados a mortalidad tras el ajuste por edad y sexo fueron: accidente cerebrovascular (OR 2,13; IC95%1,21−3,76), insuficiencia renal crónica (OR 4,38; IC95%1,91−10,04), índice de Charlson (OR 1,19; IC95%1,02−1,38), APACHE II (OR 1,07; IC95%1,02−1,12) y SOFA (OR 1,14; IC95%1,03−1,27).

DiscusiónNuestra tasa de VMI fue inferior a la declarada por Johnson et al. en Estados Unidos en 2018 (0,59%). La mortalidad intrahospitalaria de nuestro estudio superó la predicha por el score de APACHE II (40%) y de SOFA (33%), sin embargo fue consistente con la reportada por Lieberman et al. en Israel y Esteban et al. en Estados Unidos.

ConclusionesSi bien la tasa de requerimiento de VMI en el servicio de emergencias fue baja, más de la mitad fallecieron durante su hospitalización. Las enfermedades cerebrovasculares y renales preexistentes y los altos puntajes en el índice de comorbilidades y en los scores de gravedad al ingreso fueron predictores independientes para mortalidad intrahospitalaria.

Population ageing has resulted in increased emergency department consultations by the elderly. In a critical illness setting they may require advanced airway management as a frequent and quick decision procedure. Although invasive mechanical ventilation may enable survival in the acute period, mortality in this age group is high. Some authors suggest providing restricted care in the frail elderly to avoid futility, but there are no local predictive models for this decision in the emergency setting.

A high burden of comorbidity and severity on admission, represented by high Charlson, APACHE II and SOFA scores, regardless of age and sex, have been identified as factors associated with in-hospital mortality. Although the rate of invasive mechanical ventilation requirement in the emergency department was low, more than half the elderly patients died during their hospital stay.

What are the implications of the study?Our findings are novel in the emergency department setting and may drive future studies on predictors of mortality in the elderly in the ED, with important practical implications for healthcare decision-making that is so essential these overcrowded settings.

In recent decades, increased life expectancy has placed the elderly as the fastest growing age group in most developed and developing countries.1,2 The Republic of Argentina has experienced the greatest population ageing in Latin America, people aged over 65 years have increased from 7% to 10.20% between 1970 and 2010.3 This demographic change is coupled with increased demand for health services, including emergency services.4,5 A study by Pines et al. reported a 26.6% increase in emergency department visits by patients over 65 years of age from 2001 to 2009 and a 131.3% increase in admissions to intensive care units (ICU).6 In addition, people from this age group are not only admitted in a more severe and complex condition than younger patients, but they also require hospitalisation more frequently and have an increased risk of adverse events.2,7,8

Advanced airway management is a common procedure in critically ill patients in the emergency department.9 However, several authors have highlighted that this setting is not designed to meet the needs of older adults.2,4,5,10,11 Although invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) may enable survival in the acute period, in-hospital and out-of-hospital mortality is high in elderly patients.9,12 IMV can be prolonged in survivors, as can hospital stay, with poor quality of life when discharged and consequent high health care costs.9 Therefore some authors suggest establishing limited care for the frail elderly to avoid futility.1,13 However, the arguments for therapeutic adjustment are based on age, quality of life on discharge or likelihood of survival, the latter two being difficult to predict in the emergency department.1,14 Furthermore, two systematic reviews suggest that instruments available in the ED should not be used as valid predictors of adverse events on discharge in older adults.15,16 Some use predictive tools in the ED for in-hospital mortality, not used in our setting.17–22 In addition, most studies on factors associated with mortality in older adults were conducted in developed countries or in patients admitted to ICU.10,23–28

Therefore, we consider it an important hospital management goal to explore the frequency of this problem at the local level in the emergency department, and to describe the characteristics and outcomes of these critical patients and identify factors associated with death.

Justification for the research studyThe current situation of elderly patients requiring airway invasion in our setting is unknown. Determining the factors associated with in-hospital mortality in patients over 65 years of age will allow us to develop a predictive tool for future health decision-making, so necessary in scenarios of overcrowding in the emergency department.

The aim of this study was to identify factors associated with in-hospital mortality in adults over 65 years of age requiring IMV in the emergency department and to estimate the rate of this procedure in this setting.

Material and methodsStudy design and scope: observational, single-centre, retrospective, cohort study in the Central de Emergencias del Adulto (CEA) of a high complexity hospital in the city of Buenos Aires, with 173,912 patients, 33% of whom are over 65 years of age. The CEA comprises three areas for the care of patients over the age of 18, classified in decreasing order of complexity as “A”, “B” and “C”. Complexity is defined as the condition of the patient on admission through triage, which consists of a clinical assessment and a brief interview. Triage receives approximately 500 consultations a day. Orotracheal intubation (OTI) is performed in area A following the rapid intubation sequence and the drug kit includes succinylcholine as a neuromuscular blocking agent in all cases.29

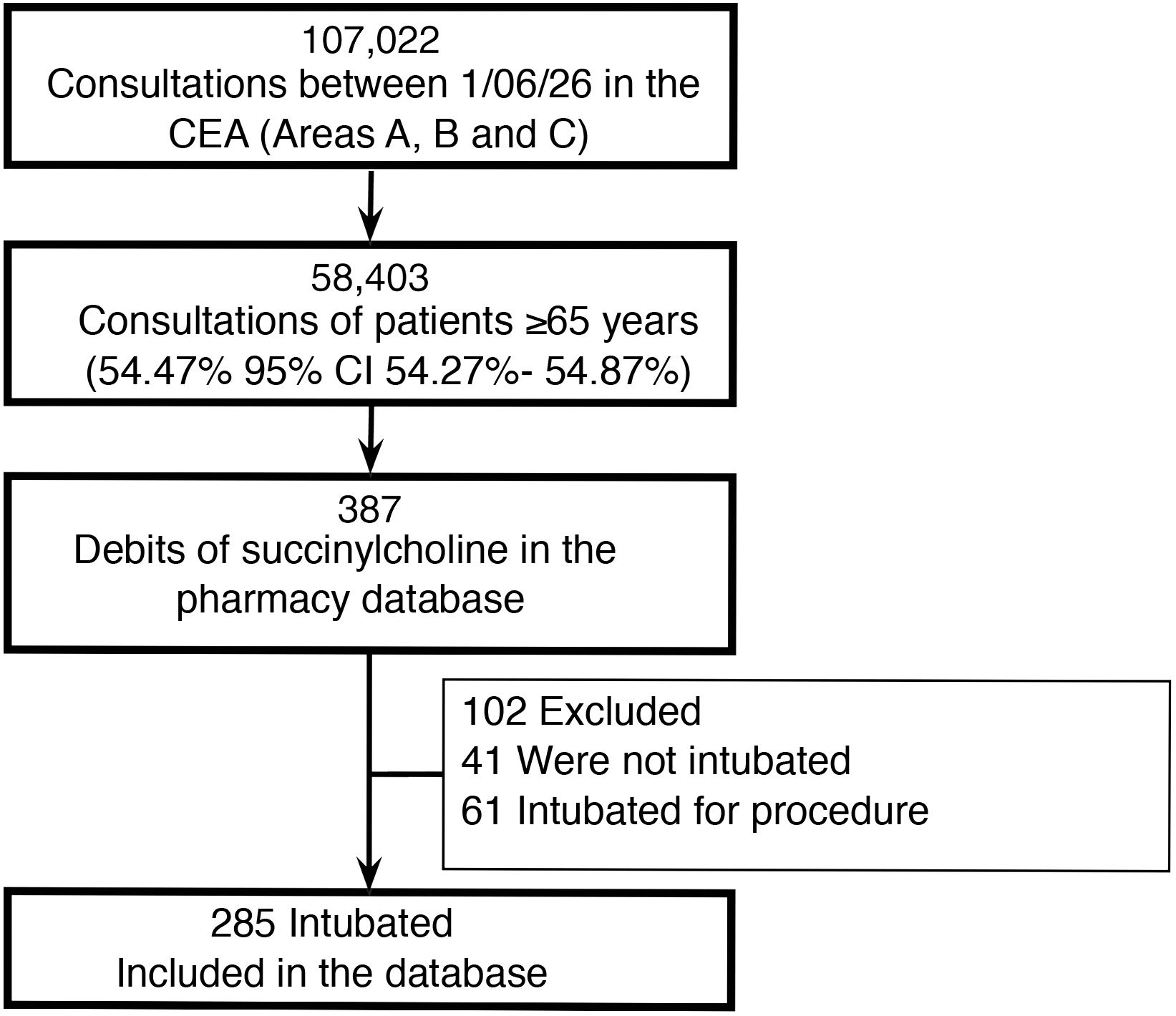

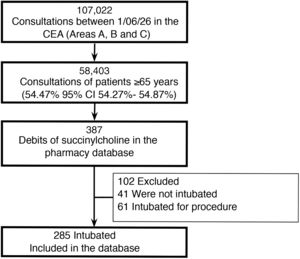

Population: all consecutive consultations between 1 June 2016 and 31 May 2018 in the emergency department of high-complexity hospital, of patients aged 65 years and older, members of the prepaid medical care plan. All cases of OTI in the CEA were included, which were extracted from high quality secondary administrative databases (debits of succinylcholine from the pharmacy administrative database) and reviewed manually by the investigators. Patients with advance directives, those requiring OTI for a procedure (e.g., emergency upper gastrointestinal video- endoscopy), those with a previous tracheostomy cannula and those referred intubated and with IMV from another hospital were excluded.

Variables: the independent variables were divided into three domains: 1) sociodemographic aspects: age and sex; 2) aspects related to previous functional status and comorbidities: functional capacity using the Katz30 and Barthel indices of activities of daily living (ADL), previous home hospitalisation, on-call consultations and hospitalisations in the last year, history and comorbidity burden using the Charlson index on admission31; 3) aspects related to acute state: main diagnosis, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score,32 Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score33 and days of IMV since intubation in the emergency department. To estimate the OTI rate, the denominator was defined as all patients aged 65 years and older consulting the CEA during the study period, and the numerator as cases of emergency OTI during care in the CEA, defined earlier. Follow-up was from admission to the CEA until discharge or in-hospital death. Mortality was the dependent variable.

Statistical analysis: the continuous variables are reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) according to their distribution. The categorical variables are shown as absolute and relative frequencies with their respective confidence intervals (95% CI). The t-test was used in the bivariate analysis (for means), the Mann–Whitney test (for medians) and χ2 test for categorical variables. Logistic regression was used to explore factors associated with death. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) are reported with their respective 95% CI. Statistical significance was considered when the p-value of a test was less than .05.

Ethical considerations: the study was approved by the hospital’s ethical committee (CEPI#3782), and conducted in accordance with the considerations on the care of clinical research participants under the Declaration of Helsinki and all its amendments. Informed consent was not required due to the study’s characteristics (observational, anonymous, and non-interventional). All the information was obtained from electronic medical records and was used by the investigators with the strictest confidentiality in accordance with current legislation: Ley Nacional de Protección de Datos Personales 25.326/00 (Ley de Habeas data) and Ley 26. 529 /09.

ResultsA total of 58,403 patients over the age of 65 attended the CEA during the study period, and 285 required IMV, which gives a rate of .48% (95% CI .43–.54). In a sensitivity analysis that included the denominator restricted to higher complexity CEA care areas (termed A and B in our institution), the rate increased to 1.97% (285/14421, 95% CI 1.76–2.21), Fig. 1.

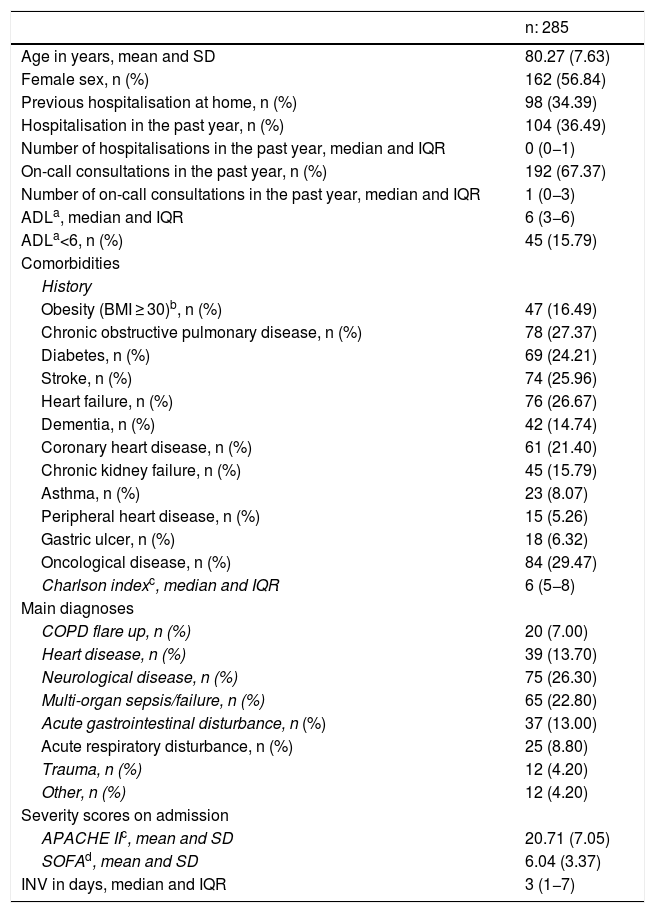

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 285 patients who required IMV in the CEA, with a mean age of 80 years. The most common reasons for IMV were neurological disorders (26.30%), sepsis/multiorgan failure (22.80%) and cardiological disorders (13.70%).

Baseline population characteristics.

| n: 285 | |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean and SD | 80.27 (7.63) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 162 (56.84) |

| Previous hospitalisation at home, n (%) | 98 (34.39) |

| Hospitalisation in the past year, n (%) | 104 (36.49) |

| Number of hospitalisations in the past year, median and IQR | 0 (0−1) |

| On-call consultations in the past year, n (%) | 192 (67.37) |

| Number of on-call consultations in the past year, median and IQR | 1 (0−3) |

| ADLa, median and IQR | 6 (3−6) |

| ADLa<6, n (%) | 45 (15.79) |

| Comorbidities | |

| History | |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30)b, n (%) | 47 (16.49) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 78 (27.37) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 69 (24.21) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 74 (25.96) |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 76 (26.67) |

| Dementia, n (%) | 42 (14.74) |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 61 (21.40) |

| Chronic kidney failure, n (%) | 45 (15.79) |

| Asthma, n (%) | 23 (8.07) |

| Peripheral heart disease, n (%) | 15 (5.26) |

| Gastric ulcer, n (%) | 18 (6.32) |

| Oncological disease, n (%) | 84 (29.47) |

| Charlson indexc, median and IQR | 6 (5−8) |

| Main diagnoses | |

| COPD flare up, n (%) | 20 (7.00) |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 39 (13.70) |

| Neurological disease, n (%) | 75 (26.30) |

| Multi-organ sepsis/failure, n (%) | 65 (22.80) |

| Acute gastrointestinal disturbance, n (%) | 37 (13.00) |

| Acute respiratory disturbance, n (%) | 25 (8.80) |

| Trauma, n (%) | 12 (4.20) |

| Other, n (%) | 12 (4.20) |

| Severity scores on admission | |

| APACHE IIc, mean and SD | 20.71 (7.05) |

| SOFAd, mean and SD | 6.04 (3.37) |

| INV in days, median and IQR | 3 (1−7) |

ADL: activities of daily living; APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; BMI: Body Mass Index; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; IQR: Interquartile Range; SD: Standard Deviation; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

One hundred and fifty-eight patients died, giving an overall in-hospital mortality rate of 55.44%. Only one death occurred during on-call care, while the remaining cases (157) occurred during subsequent unscheduled hospitalisation, which triggered the same acute episode as the reason for consultation or admission.

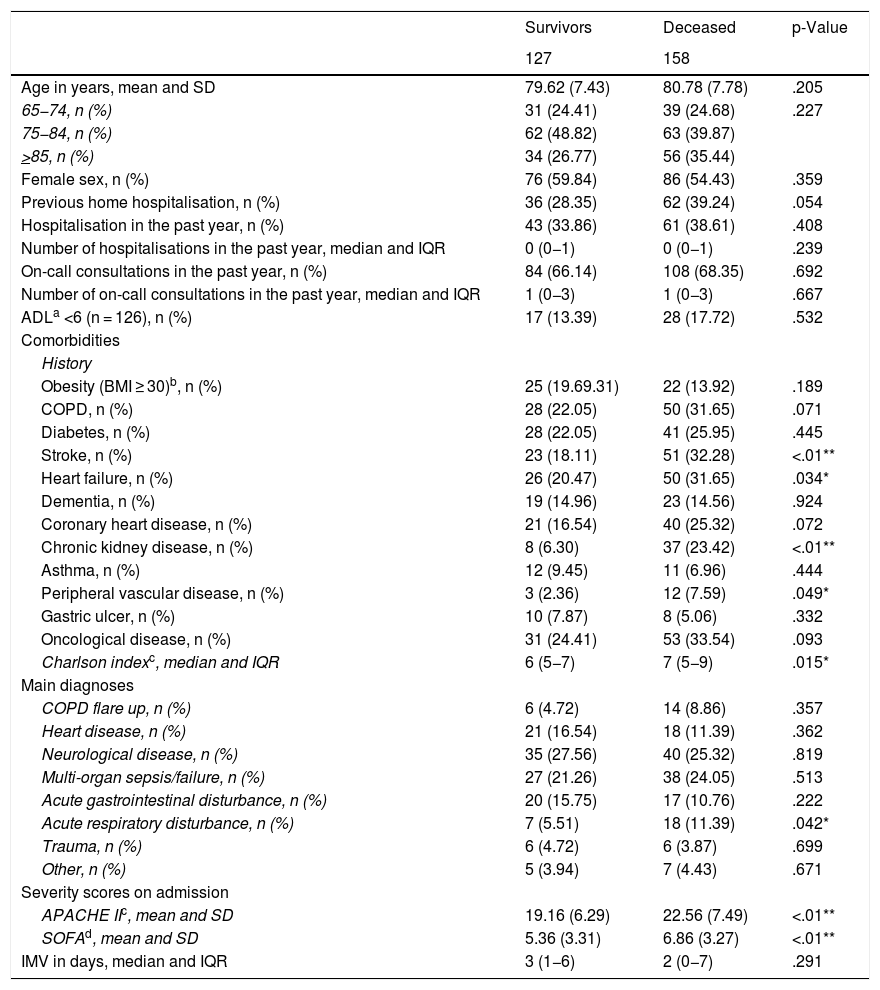

The patients were classified according to in-hospital mortality to explore associated factors, as shown in Table 2. In terms of the main diagnosis relating to the requirement for IMV, the deceased patients had a higher rate of acute respiratory illness compared to the survivors (11.39% vs. 5.51% respectively; p = .042).

Characteristics according to subgroup (survivors and deceased).

| Survivors | Deceased | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 127 | 158 | ||

| Age in years, mean and SD | 79.62 (7.43) | 80.78 (7.78) | .205 |

| 65−74, n (%) | 31 (24.41) | 39 (24.68) | .227 |

| 75−84, n (%) | 62 (48.82) | 63 (39.87) | |

| >85, n (%) | 34 (26.77) | 56 (35.44) | |

| Female sex, n (%) | 76 (59.84) | 86 (54.43) | .359 |

| Previous home hospitalisation, n (%) | 36 (28.35) | 62 (39.24) | .054 |

| Hospitalisation in the past year, n (%) | 43 (33.86) | 61 (38.61) | .408 |

| Number of hospitalisations in the past year, median and IQR | 0 (0−1) | 0 (0−1) | .239 |

| On-call consultations in the past year, n (%) | 84 (66.14) | 108 (68.35) | .692 |

| Number of on-call consultations in the past year, median and IQR | 1 (0−3) | 1 (0−3) | .667 |

| ADLa <6 (n = 126), n (%) | 17 (13.39) | 28 (17.72) | .532 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| History | |||

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30)b, n (%) | 25 (19.69.31) | 22 (13.92) | .189 |

| COPD, n (%) | 28 (22.05) | 50 (31.65) | .071 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 28 (22.05) | 41 (25.95) | .445 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 23 (18.11) | 51 (32.28) | <.01** |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 26 (20.47) | 50 (31.65) | .034* |

| Dementia, n (%) | 19 (14.96) | 23 (14.56) | .924 |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 21 (16.54) | 40 (25.32) | .072 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 8 (6.30) | 37 (23.42) | <.01** |

| Asthma, n (%) | 12 (9.45) | 11 (6.96) | .444 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 3 (2.36) | 12 (7.59) | .049* |

| Gastric ulcer, n (%) | 10 (7.87) | 8 (5.06) | .332 |

| Oncological disease, n (%) | 31 (24.41) | 53 (33.54) | .093 |

| Charlson indexc, median and IQR | 6 (5−7) | 7 (5−9) | .015* |

| Main diagnoses | |||

| COPD flare up, n (%) | 6 (4.72) | 14 (8.86) | .357 |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 21 (16.54) | 18 (11.39) | .362 |

| Neurological disease, n (%) | 35 (27.56) | 40 (25.32) | .819 |

| Multi-organ sepsis/failure, n (%) | 27 (21.26) | 38 (24.05) | .513 |

| Acute gastrointestinal disturbance, n (%) | 20 (15.75) | 17 (10.76) | .222 |

| Acute respiratory disturbance, n (%) | 7 (5.51) | 18 (11.39) | .042* |

| Trauma, n (%) | 6 (4.72) | 6 (3.87) | .699 |

| Other, n (%) | 5 (3.94) | 7 (4.43) | .671 |

| Severity scores on admission | |||

| APACHE IIc, mean and SD | 19.16 (6.29) | 22.56 (7.49) | <.01** |

| SOFAd, mean and SD | 5.36 (3.31) | 6.86 (3.27) | <.01** |

| IMV in days, median and IQR | 3 (1−6) | 2 (0−7) | .291 |

ADL: Activities of daily living; APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; BMI: Body Mass Index; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

The patients who died, compared to the survivors, had greater comorbidities or pre-existing disease burden on admission, such as stroke and chronic kidney failure (CKF) (p < .01), heart failure (p = .034) and peripheral vascular disease (p = .049), and higher severity scores on admission (p < .01).

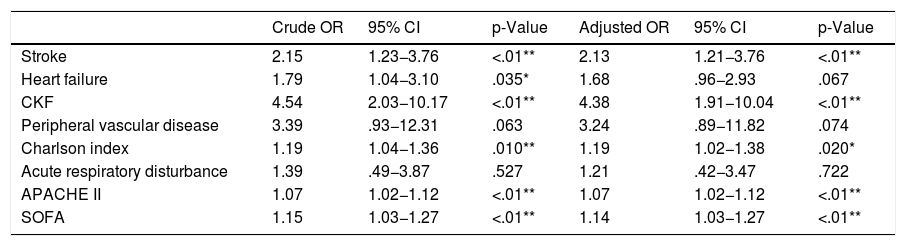

Table 3 shows the corresponding crude and adjusted OR with their respective 95% CI. The factors associated with death in the univariate analysis were stroke, heart failure, CKF, Charlson Index, APACHE II, and SOFA. After adjustment for sex and age, all remained statistically significant risk factors, except for heart failure.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with death.

| Crude OR | 95% CI | p-Value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | 2.15 | 1.23−3.76 | <.01** | 2.13 | 1.21−3.76 | <.01** |

| Heart failure | 1.79 | 1.04−3.10 | .035* | 1.68 | .96−2.93 | .067 |

| CKF | 4.54 | 2.03−10.17 | <.01** | 4.38 | 1.91−10.04 | <.01** |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 3.39 | .93−12.31 | .063 | 3.24 | .89−11.82 | .074 |

| Charlson index | 1.19 | 1.04−1.36 | .010** | 1.19 | 1.02−1.38 | .020* |

| Acute respiratory disturbance | 1.39 | .49−3.87 | .527 | 1.21 | .42−3.47 | .722 |

| APACHE II | 1.07 | 1.02−1.12 | <.01** | 1.07 | 1.02−1.12 | <.01** |

| SOFA | 1.15 | 1.03−1.27 | <.01** | 1.14 | 1.03−1.27 | <.01** |

Crude and age- and sex-adjusted odds ratios (OR) were reported.

APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; CKF: Chronic Kidney Failure; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Our results show that more than half the consultations in the CEA were by patients over 65 years of age, but with a IMV rate of five per thousand consultations, which quadruples in the sensitivity analysis when considering a denominator restricted to the most critical areas. However, in terms of prognosis, more than half the patients died during hospitalisation, which is not insignificant in terms of health costs.34,35 This study aims to identify variables included in the comprehensive geriatric assessment and other clinical variables on admission that are associated with an increased risk of death after emergency OTI. The factors associated with death after adjustment for age and sex were stroke, CKD, Charlson Index, APACHE II and SOFA.

Our rate of emergency OTI in the over-65 s was similar (.48% with 95% CI .43–.54) to that reported by Johnson in the United States (.59%), and the same paper reports a relative decrease of 29% (95% CI 17%, 38%) between 1999 and 2014.36 However, the similarity between the populations is worth noting: age 80.27 (SD 7.63) years and 56.84% female in our study, and 80 (SD 8) years and 54% female in the American study. However, in-hospital mortality in our study exceeded that predicted by the APACHE II (40%) and SOFA (33%) scores, although the age difference in this other cohort is worth noting, the patients were younger (59 years) and therefore there were probably other reasons for admission.37 Survival was consistent with that reported by Lieberman et al. and Esteban et al.12,38 However, Ouchi et al. report 33% mortality in older adults after OTI in the ED, with differences between age groups.9 Because previous studies found no differences in mortality with respect to age,7,23,26 we decided not to explore this again. The elderly cannot be defined as frail by age alone, but rather through a complex combination of comorbidities, quality of life and functional capacity.7 Our study population had a high burden of comorbidity as represented by the high Charlson Index, yet functional capacity reported through ADL was high and a very few had an ADL score of less than 6, which is considered a predictor of mortality in other publications.15,23 Decisions about the extent of resuscitation effort (or in this case requirement for OTI in an acute setting) should perhaps consider these assessments, in addition to patient and family preferences (e.g., advance directives).13

Concern about the increasing elderly population in ICUs is longstanding.35,39,40 The magnitude of the problem lies in its impact on the health system, in terms of healthcare costs. In our hospital, every day on IMV costs approximately 680 US dollars. This is an economic and ethical problem that healthcare providers must analyse and anticipate carefully, i.e., old age is associated with a high prevalence of chronic diseases and functional impairment, with limited life expectancy, occasionally poor quality of life, and a priori they are considered patients with a poor prognosis in ICU.34 This clearly implies greater demand for health services, and therefore, ICU beds, which will make it increasingly necessary to streamline the available resources.

However, we should mention some limitations that are inherent to the study design. Firstly, it is a retrospective study design, with some variables of interest that could not be obtained due to missing or unavailable data due to feasibility, such as the Barthel index, with only 16 records, and therefore we did not include it in the results. We would probably have gained additional information if we had considered other variables such as out-of-hospital mortality, quality of life after discharge or whether the patients who were not intubated in the ED were intubated during their hospital stay; however, although interesting, this information is not within the objectives of this paper. On the other hand, the magnitude of the problem to be addressed (in terms of overall in-hospital mortality), which reflects the uncertain prognosis in the elderly and the importance of these local data from a management perspective are a strength of the study. In addition, our novel approach with this paper focussed on the scope of the work, centred on the central ED rather than closed units (like most published works), which represents the gateway to hospital in many acute clinical scenarios. Secondly, the cut-off point of 65 years to categorise older adults could be questioned, but we use it routinely in our country because of the retirement age and the mean age was 83 years.23 In addition, therapeutic adjustment after OTI could have contributed to an increase in the mortality rate. Finally, the fact that this was a single-centre study, and the small sample could make it difficult to generalise the results.

In conclusion, after adjusting for sex and age, some pre-existing comorbidities and the severity scales used on admission are considered risk factors for death. This information could perhaps be a starting point for creating a tool to predict poor prognosis. Given the forecasts on changing the population pyramid and this current problem, further studies are required to assess the use of hospital resources (in terms of health costs), and survival and quality of life after hospital discharge in this population, to respond to the anticipated demand for resources in critical care units in years to come.

ConclusionsAlthough the rate of airway instrumentation in the emergency department was low, more than half the elderly patients died during hospitalisation. Pre-existing cerebrovascular and renal comorbidities, as well as severity on admission, reflected in the high APACHE II and SOFA scores, were associated with greater in-hospital mortality, regardless of age and sex.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz VR, Grande-Ratti MF, Martínez B, Midley A, Sylvestre V, Mayer GF. Factores asociados a mortalidad intrahospitalaria en pacientes adultos mayores con asistencia ventilatoria mecánica invasiva en el servicio de urgencias. Enferm Intensiva. 2021;32:145–152.