Critical illness in paediatric patients includes acute conditions in a healthy child as well as exacerbations of chronic disease, and therefore these situations must be clinically managed in Critical Care Units. The role of the paediatric nurse is to ensure the comfort of these critically ill patients. To that end, instruments are required that correctly assess critical comfort.

ObjectiveTo describe the process for validating the content of a paediatric critical comfort scale using mixed-method research.

Material and methodsInitially, a cross-cultural adaptation of the Comfort Behaviour Scale from English to Spanish using the translation and back-translation method was made. After that, its content was evaluated using mixed method research. This second step was divided into a quantitative stage in which an ad hoc questionnaire was used in order to assess each scale's item relevance and wording and a qualitative stage with two meetings with health professionals, patients and a family member following the Delphi Method recommendations.

ResultsAll scale items obtained a content validity index >0.80, except physical movement in its relevance, which obtained 0.76. Global content scale validity was 0.87 (high).

During the qualitative stage, items from each of the scale domains were reformulated or eliminated in order to make the scale more comprehensible and applicable.

ConclusionsThe use of a mixed-method research methodology during the scale content validity phase allows the design of a richer and more assessment-sensitive instrument.

La enfermedad crítica en el paciente pediátrico incluye desde una patología aguda en un niño sano a una agudización de una enfermedad crónica, hecho que ha conllevado centrar su atención clínica en las Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos Pediátricos. El rol del/la enfermero/a pediátrico/a se centra también en promover el confort en estos pacientes críticos. Por este motivo, es necesario disponer de instrumentos de medida que permitan un correcto sensado del grado de confort.

ObjetivoDescribir el proceso de validación de contenido de una escala de confort crítico pediátrico mediante el empleo de una metodología mixta.

Material y métodosSe realizó una adaptación transcultural del inglés al español mediante el método de traducción-retraducción de la Comfort Behavior Scale. Posteriormente, se validó el contenido de la misma mediante una metodología mixta. Esta segunda etapa se dividió en una fase cuantitativa empleando un cuestionario ad hoc donde se valoró la relevancia/pertinencia y el redactado de cada dominio/ítem de la escala y en una cualitativa donde se realizaron dos reuniones con profesionales sanitarios, pacientes y un familiar siguiendo las recomendaciones de la metodología Delphi.

ResultadosTodos los ítems y dominios obtuvieron un índice de validez de contenido >0,80, exceptuando el movimiento físico, en su relevancia, que obtuvo un 0,76. El índice global de validez de contenido de la escala fue de 0,87 (elevado).

Durante la fase cualitativa se reformularon y/o eliminaron ítems de cada uno de los dominios de la escala para hacerla más comprensible y aplicable.

ConclusionesEl empleo de una metodología mixta de validación de contenido otorga riqueza y sensibilidad evaluatoria al instrumento a diseñar.

The creation of instruments requires the use of different processes that make it possible to obtain evidence of their validity and reliability for measuring phenomena. Quantitative methodology is usually used for this, by calculating the content validity index. The simultaneous combination of mixed qualitative and quantitative methodologies during the content validation process makes it possible to counterbalance the intrinsic weaknesses of each methodology and reduce the need to perform more than one test during the creation or adaptation of a questionnaire in the field of health.

In the specific case of the comfort phenomenon and its measurement in the context of critical patients, and most especially critical paediatric patients, no scale has been validated in Spanish that makes it possible to explore an aspect as subjective as comfort or discomfort. Nevertheless, this is necessary to the quality of the care given to patients.

Comfort is a fundamental aspect of establishing patient health and early recovery. The results of this study show that using mixed methodology in the validation of a paediatric critical comfort scale improves the instrument being designed, improving semantic comprehension and raising its evaluative sensitivity.

Implications of the studyKnowing the procedure that combines quantitative and qualitative methodologies to validate instruments allows professionals to acquire knowledge that they will be able to apply in similar contexts within their clinical practice.

Moreover, having a validated instrument for measuring and analysing comfort levels in critical paediatric patients offers more in-depth knowledge of the phenomenon. This permits correct comprehension of each part and dimension of the concept, thereby increasing exactitude in the determination of the degree of comfort in these patients.

Critical disease in paediatric patients includes acute pathology in an otherwise healthy child, the intensification of a chronic disease, trauma or the need to perform a planned invasive procedure.1 Care for these paediatric patients has to take the severity of their pathology into account, representing a real or potential threat to their life and raising the possibility of death and pain.2 Additionally, during the process of diagnosing and treating critical paediatric patients two conditions may arise: a critical situation with a current or potential risk of suffering life-threatening complications, or a reversible pathological process.3 This has led to them chiefly receiving care in Paediatric Intensive Care Units.1 These units have mainly centred on treating pathologies, focusing on recovery and maintaining cardiorespiratory, neurological and renal functions. However, they sometimes forget to satisfy other needs that go beyond physiological aspects and are emotional, such as sleep4 or comfort. In connection with the latter, one individual who has researched this concept is the gerontologist Katherine Kolcaba, who developed Comfort Theory. She defines this concept as the state experienced by those who receive interventions to increase comfort. This is the immediate and holistic experience of feeling stronger when the needs for three types of comfort are met. These are: relief or the satisfaction of a need, peace of mind or calm, and transcendence – the state in which one is above one's own problems or pain. The four contexts in which this can take place must also be taken into account: physical – bodily sensations; psychospiritual – internal awareness of myself: self-esteem and self-concept; ambient and social.5,6 The concept of comfort is important in everyday clinical practice, as it is a patient care indicator and aids nurses to plan and design care in any treatment environment or context.5 Therefore, and taking into account the fact that activities as well as subsequent care during the management of a critical paediatric patient lead to discomfort, it would be prudent to detect it at an early stage and manage it clinically.

The definition of health by the World Health Organisation (1948) states that it consists of complete physical, mental and social comfort. This context shows that critical disease requires the development of scales and indexes to aid the measurement of patients’ health.7 There is also growing interest in transcultural and transidiomatic studies, which thanks to intense communication and information exchange have helped to facilitate the adaptation of scales to different cultures.8,9 Due to all of the above reasons, in recent years the adaptation of instruments between cultures has increased in all areas of evaluation.10 This is because it is becoming increasingly necessary to have measuring instruments in the field of health that can be used in clinical practice and research.11

It is both complex and expensive to prepare a questionnaire. The construct has to be defined, together with the purpose of the scale, the population, format and composition in terms of items, while distortions have to be detected and the replies have to be coded.12,13

Instrument or scale validity is an essential aspect of this whole process of creation. If a questionnaire is in a language other than its original one then it has to be adapted to the medium in which it is to be used. Its psychometric characteristics must be analysed to ensure that they are suitable to measure what it was designed to measure.14 To speed up this process and reduce costs texts that have been created and validated in other languages are usually used. The majority of these texts are in English, although they are transculturally adapted.15,16

The most widely-used methodology for this procedure is that of translation-retranslation (semantic and not literal) by two bilingual healthcare professionals. This process follows the recommendation of the International Test Commission,12,17 as this method is considered to be the most complete as well as the one which ensures the highest quality.17

Once the questionnaire has been adapted to the target language the process then centres on validating its content, i.e., checking that it measures what it should measure.18 This is of key important for the design of the questionnaire as well as in checking the usefulness of the measurements it makes.19

This validation of content consists of expert evaluation8,20,21 of the object/issue of the study in terms of the relevance and pertinence of the items included in a scale.11 This is a unitary process22 and it qualitatively evaluates whether the instrument covers the dimensions of the phenomenon that it is designed to measure.14

It is now important to combine both methodologies (qualitative and quantitative) when preparing scales. This is because the integration of both types of approach in the study of certain phenomena may counterbalance the deficiencies that arise when a single type of methodology is used.23

This work describes a critical paediatric patient comfort scale validation process using mixed methodology.

Material and methodsThe design used in this work corresponds to a mixed validation study of the content of a critical paediatric patient comfort scale.

The measuring instrument used in this study was the validated Comfort Behaviour Scale, as this is one of the instruments most widely used for the evaluation of the degree of critical paediatric patient comfort. The Comfort Behaviour Scale (2005)24 derives from the Comfort Scale (1992).25 These are the only tools that have been developed to evaluate the comfort of critical paediatric patients aged from 0 to 18 years old. The Comfort Scale and Comfort Behaviour Scale consist of measuring 6 behavioural parameters (wakefulness, degree of agitation/calm, crying or respiratory response, physical movement, muscle tone and facial expression) together with 2 physiological parameters in the 1992 scale (heart rate and blood pressure). The main difference between both scales is that the later scale does not measure the two physical parameters included in the original one: blood pressure and heart rate. This is due to the fact that Van Dijk states that in a critical patient unit physical parameters may be affected by different factors, drugs or medication above all.26

The transcultural adaptation process of the Comfort Behaviour Scale used the semantic (not literal) translation-retranslation method. This was applied by four healthcare professionals (two paediatricians and two paediatric intensive care nurses. They are all bilingual in both languages (Spanish and English). Once the process of translation-retranslation had finished a discussion group was formed, composed of the four individuals involved and the chief researcher, to analyse the instrument in qualitative terms. In this meeting the semantic equivalence of both versions obtained from the translation-retranslation process was compared with the original scale, reaching agreement on the best expression and thereby creating the Spanish version of the scale.

Once the Spanish version of the critical paediatric patient comfort scale had been established the validity of the content was determined.

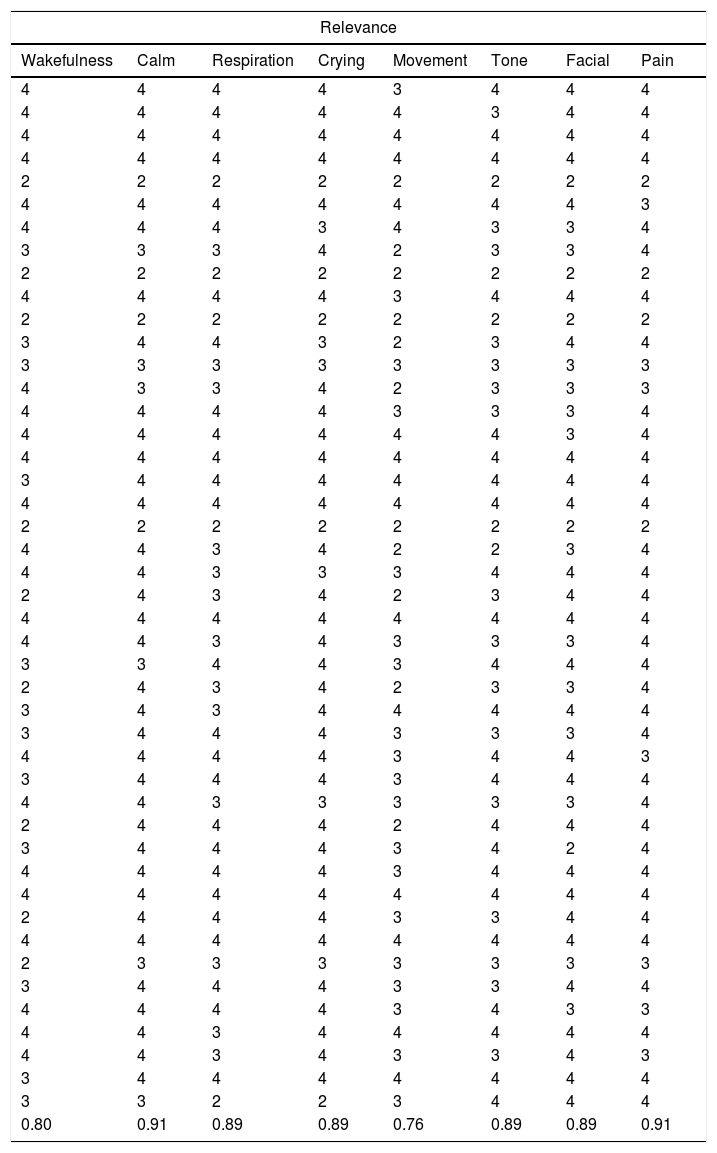

The quantitative phaseIt was firstly decided to use quantitative methodology and an ad hoc questionnaire which was evaluated on a Likert-type scale. Scores on this scale were from 0 (not at all) to 10 (very much) for relevance/pertinence. Relevance was understood to refer to the quality or condition of being relevant, its importance or meaning, while pertinence was understood to be the concept of pertaining or referring to something, i.e., that evaluated the concept of comfort. The expression of each domain/item of the paediatric comfort scale was evaluated in the above terms. To improve the precision of the data obtained and thereby to ensure the internal and external validity of the instrument (understood as the capacity of the scale to be used not only in the context of this study, but also in similar contexts and/or ones with the same structural characteristics in the healthcare sector) the questionnaire was administered to nurses and paediatricians. They had at least 2 years’ experience in caring for critical paediatric patients in three tertiary care hospitals with a Paediatric Intensive Care Unit. The professionals involved in this phase were contacted by email or telephone. To analyse the data extracted from the answered questionnaires and to calculate the validity index of each item and the overall validity index for the content of the scale, the scores were classified in four groups: 1 (not relevant/not pertinent): 0–2; 2 (not very relevant/not very pertinent): 3–5; 3 (relevant/pertinent): 6–8; 4 (very relevant/very pertinent): 9–10.

An informative page was prepared together with the questionnaire. This contained study data and a description of its purpose and aims. The study was subjected to evaluation by the Ethics and Clinical Research Committee of the hospital where it was undertaken, as well as the Bioethics Committee of Barcelona University. An informed consent form was designed to comply at all times with current personal data protection law (Organic Law 15/1999 of December, on personal data protection).

Data analysisThe aim of data analysis in the quantitative phase was to determine the content validity index (CVI). Scale content validity here (S-CVI) refers to the degree to which a scale contains an appropriate number of items to evaluate a concept. This is therefore an important aspect to be taken into account by clinicians and/or researchers who require high quality measurements.27 It is the degree to which a set of items that are grouped together constitute a suitable operational definition of a construct.28

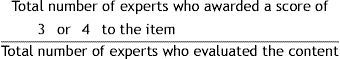

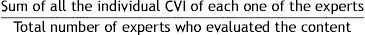

In this project it was decided to calculate the item level content validity index (I-CVI) and the scale level content validity index (S-CVI) using the methodology proposed by Lynn (1986) and Polit and Tatano (2006).28,29 The following formulas were used:

Item level content validity index (I-CVI): the total number of experts who awarded a score of 3 or 4 to an item (relevant/pertinent or very relevant/very pertinent). To be considered acceptable it must be >0.78, and it is calculated using the following formula28,29:

Scale level content validity index (S-CVI): this is obtained by averaging all of the scores obtained in the I-CVI, thereby establishing the overall validity of the scale and its applicability to other contexts. Validity is considered to be high at values > 0.80, and it is calculated in the following way27:

Data deriving from these questionnaires were analysed using the Microsoft® Excel program and the IBM SPSS® v.17 statistical package.

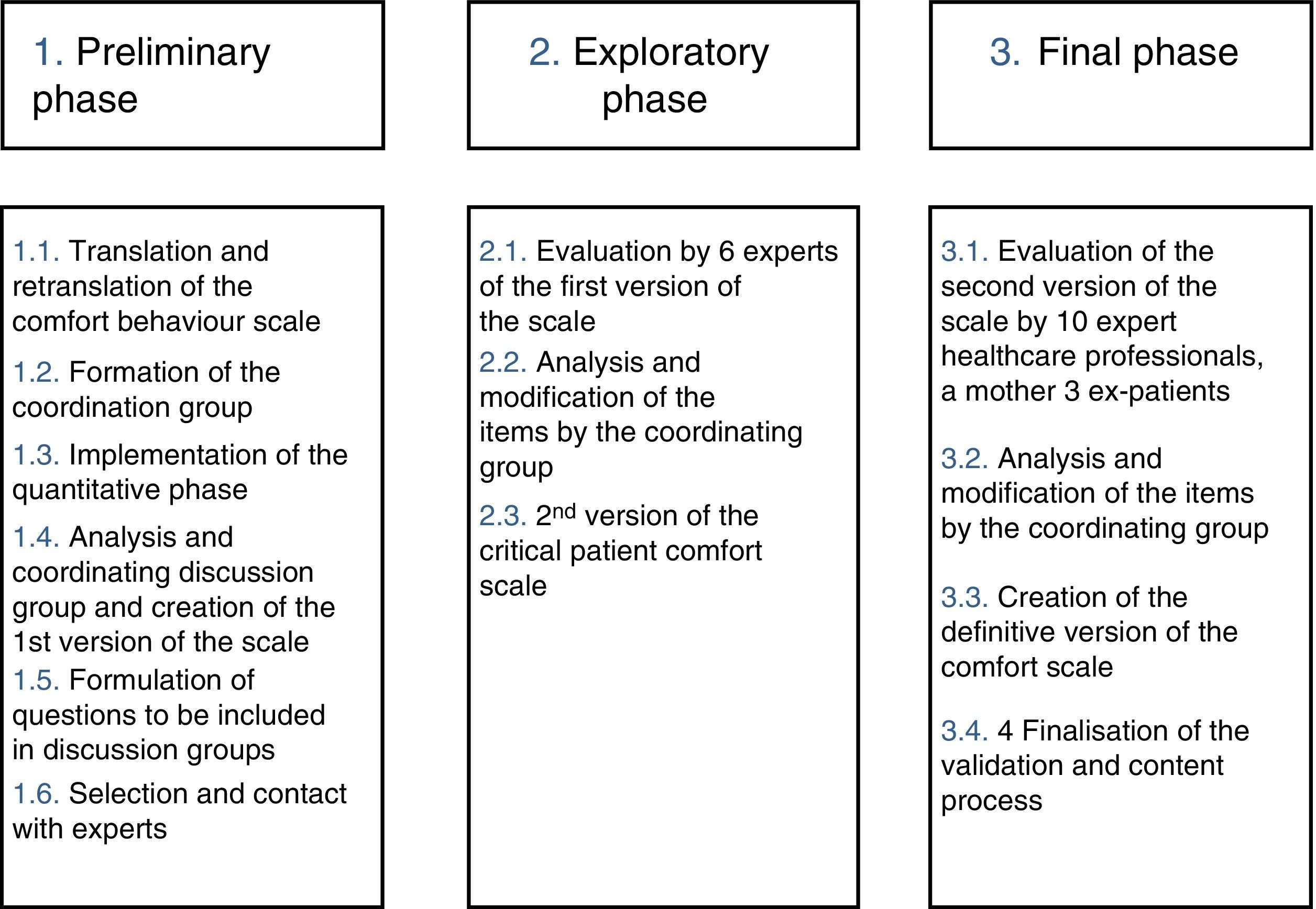

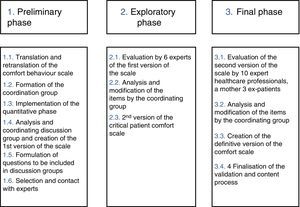

The qualitative phaseQualitative methodology was used in a second phase of the process to determine the validity of the content of the Comfort Behaviour Scale. This followed the recommendations set by Delphi methodology30 (Fig. 1), in which the agreed opinion of a group of expert healthcare workers in the management of critical paediatric patients was obtained. This is why the inclusion criterion was 5 years experience in this field. The opinions of the chief actors in this study (patients and their families) were also obtained. This method is an effective and systematic procedure for gathering the opinions of experts on a particular subject so that they can be used to prepare a questionnaire. The Delphi Method for validating questionnaires and scales has been used in many studies and fields of knowledge, including the health sciences.31–33 This methodology is divided into three phases: the preliminary or organisational phase of the coordinating group, which is composed of the chief researcher and a collaborator together with the experts; the exploratory phase, which corresponds to analysis of the concept of comfort and the instrument; and the final phase, in which the data gathered is synthesised and the instrument is changed in the proposed ways, thereby preparing the definitive scale.

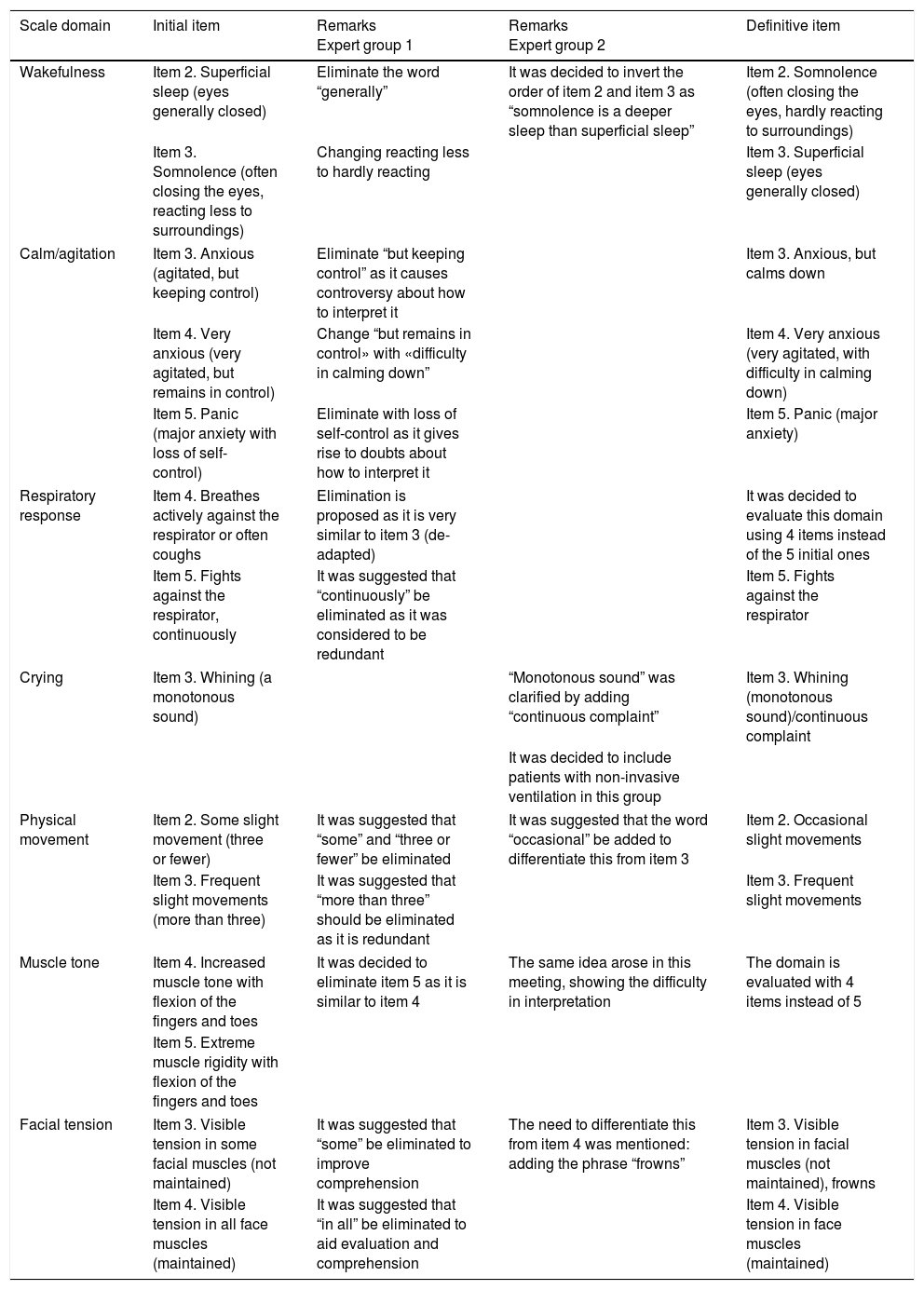

Two meetings were held during this study. Participation in these was completely voluntary, and contact was by email, telephone or face-to-face. Everybody who agreed to take part was sent (by email) the scale to evaluate, so that they could read it and analyse it prior to the day of the meeting. The first meeting took place only with experts, and as Polit and Beck34 recommend a minimum of five, six healthcare professionals were selected (4 paediatricians and 2 nurses). They had wide experience in the management of critical paediatric patients, given that they are the most involved in their care, and are also the most interested in promoting their comfort. The main aim of this first meeting was to qualitatively evaluate each item in the scale to make it more comprehensible, so that both professions were not differentiated here. A second meeting was held afterwards with patients, professionals and a family member, and all of them were considered to be experts in the field of promoting comfort. 10 specialist paediatric nurses took part in this meeting, together with two paediatric staff doctors with more than 10 years’ experience in managing patients of this type. The mother of a boy admitted to the unit where the study took place for more than 3 months was also invited, together with 3 adolescent ex-critical patients. The meeting started by informing the participants about the replies, justifications and changes proposed by the other experts during the first meeting. They were then each asked to give their opinion and evaluate the instrument. All opinions of the scale were given the same weighting regardless of whose they were. This was because the aim of the meeting was to qualitatively evaluate each one of the items on the scale to ensure they were understood correctly and that comfort was understood to mean the same by all of the agents involved: professionals (mainly paediatricians and nurses), patients and their family.

Data from this phase were analysed by means of literal transcription and modification of the items/domains agreed by both discussion groups.

ResultsQuantitative phase resultsA total of 45 questionnaires were obtained: 36 were answered by nurses and 9 by paediatricians with an average of 12.88±7.1 (1–34) years working in the management of critical paediatric patients. The majority of the professionals who took part in the quantitative phase work in the Hospital Sant Joan de Déu (n=29), followed by the Hospital Vall d’Hebron (n=9). Of the total number, 43 worked in a Paediatric Intensive Care Unit and two worked in the Paediatric Medical Emergencies System.

All of the items and domains scored an I-CVI for relevance/pertinence and expression >0.80. Nevertheless, the item “physical movement” scored 0.76 for relevance (a revisable item), although it scored more than enough (0.84) for expression (Table 1).

Content validity index according to relevance and expression, grouped by Comfort Behaviour Scale domains.

| Relevance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wakefulness | Calm | Respiration | Crying | Movement | Tone | Facial | Pain |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.91 |

| Expression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wakefulness | Calm | Respiration | Crying | Movement | Tone | Facial | Pain |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.82 |

To centre on the results in the scale level content validity index or S-CVI, this scored 0.87 (high), for relevance/pertinence as well as for expression, thereby guaranteeing the validity of the overall content of the instrument. However, the text of some items in the scale was modified after this analysis to improve their comprehension.

This quantitative analysis showed that the only domain to be revised (not eliminated) was the one on physical movement, above all in how it was expressed.

Qualitative phase resultsThe experts were asked to evaluate all of the domains (n=7) and items (n=35) on the scale, to increase their validity and thereby counterbalance any possible deficiencies in the quantitative methodology. Each meeting of experts lasted for 1 and a half hours. The main changes to the comfort scale during this qualitative content validation phase are shown in Table 2.

Proposals and changes made to the comfort scale during the expert groups.

| Scale domain | Initial item | Remarks Expert group 1 | Remarks Expert group 2 | Definitive item |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wakefulness | Item 2. Superficial sleep (eyes generally closed) | Eliminate the word “generally” | It was decided to invert the order of item 2 and item 3 as “somnolence is a deeper sleep than superficial sleep” | Item 2. Somnolence (often closing the eyes, hardly reacting to surroundings) |

| Item 3. Somnolence (often closing the eyes, reacting less to surroundings) | Changing reacting less to hardly reacting | Item 3. Superficial sleep (eyes generally closed) | ||

| Calm/agitation | Item 3. Anxious (agitated, but keeping control) | Eliminate “but keeping control” as it causes controversy about how to interpret it | Item 3. Anxious, but calms down | |

| Item 4. Very anxious (very agitated, but remains in control) | Change “but remains in control» with «difficulty in calming down” | Item 4. Very anxious (very agitated, with difficulty in calming down) | ||

| Item 5. Panic (major anxiety with loss of self- control) | Eliminate with loss of self-control as it gives rise to doubts about how to interpret it | Item 5. Panic (major anxiety) | ||

| Respiratory response | Item 4. Breathes actively against the respirator or often coughs | Elimination is proposed as it is very similar to item 3 (de-adapted) | It was decided to evaluate this domain using 4 items instead of the 5 initial ones | |

| Item 5. Fights against the respirator, continuously | It was suggested that “continuously” be eliminated as it was considered to be redundant | Item 5. Fights against the respirator | ||

| Crying | Item 3. Whining (a monotonous sound) | “Monotonous sound” was clarified by adding “continuous complaint” | Item 3. Whining (monotonous sound)/continuous complaint | |

| It was decided to include patients with non-invasive ventilation in this group | ||||

| Physical movement | Item 2. Some slight movement (three or fewer) | It was suggested that “some” and “three or fewer” be eliminated | It was suggested that the word “occasional” be added to differentiate this from item 3 | Item 2. Occasional slight movements |

| Item 3. Frequent slight movements (more than three) | It was suggested that “more than three” should be eliminated as it is redundant | Item 3. Frequent slight movements | ||

| Muscle tone | Item 4. Increased muscle tone with flexion of the fingers and toes | It was decided to eliminate item 5 as it is similar to item 4 | The same idea arose in this meeting, showing the difficulty in interpretation | The domain is evaluated with 4 items instead of 5 |

| Item 5. Extreme muscle rigidity with flexion of the fingers and toes | ||||

| Facial tension | Item 3. Visible tension in some facial muscles (not maintained) | It was suggested that “some” be eliminated to improve comprehension | The need to differentiate this from item 4 was mentioned: adding the phrase “frowns” | Item 3. Visible tension in facial muscles (not maintained), frowns |

| Item 4. Visible tension in all face muscles (maintained) | It was suggested that “in all” be eliminated to aid evaluation and comprehension | Item 4. Visible tension in face muscles (maintained) | ||

This study aimed to guarantee a high level of content validity for the Spanish version of the Comfort Behaviour Scale, an instrument designed to evaluate the degree to which critical paediatric patients feel comfortable. Mixed methodology was used, as was the case in previous studies.35,36 This scale is designed for use in Paediatric Intensive Care Units, to be administered by qualified nurses in the comprehensive management and evaluation of critical paediatric patients at all times during clinical treatment and care. Quantitative methodology is currently the most widely used and reliable way of validating the content of a new instrument, according to the experts.37–40 This is also the case for calculating the content validity index,27–29,41 so that these determinations are not lacking from this work.

As was found in previous studies, the validated scale gave good quantitative results respecting the validity of its content.27–29 Delphi methodology was also found to be effective in validating the content of our instrument, and this was also the case in previous studies.23,35,36 This methodology is based on a dynamic method of feedback and decision-making23 that helps to structure group communication processes (such as the one selected for use in the qualitative methodology of this study). This means that a group of individuals is able to solve complex problems.42 Using Delphi methodology group communication and the in situ evaluation of each one of the items in the scale35,36 it was possible to determine and modify aspects of the same that were not properly comprehended and which had not been detected in the quantitative phase of content validity determination. This has also shown the soundness in this study of the statement by Gil and Pascual, that “Delphi methodology seems to be a good procedure within the framework of expert methods to guarantee a high level of content validity, and it also complements the usual process by adding flexibility and feedback to the same; in comparison with a traditional expert method”.23

Although they did not have the content validity data corresponding to the Comfort Scale25 and Comfort Behaviour Scale24 during qualitative evaluation of the items included in the paediatric comfort scale, all of the experts scored them as correct. Nevertheless, it was recommended that the relevance of the “physical movement” item be revised.

Regarding the qualitative phase, all of the members who took part in the Delphi meetings agreed that it was important to adapt some items by eliminating confusing terms or ones that repeated a meaning in each one of the dimensions in the instrument (alert, calm/agitation, respiratory response/crying, physical movement, muscle tone and facial tension).

A qualitative-quantitative approach makes it possible to design instruments that record personal perceptions that can be quantified,43 such as those obtained after both meetings held during the qualitative phase of validation of the content of the Comfort Behaviour Scale. This approach also seems to improve the quality of the result as well as the trustworthiness of the instrument.31 This was verified in our study with the reformulation of the text of items in each one of the methodological phrases used.

ConclusionsThe use of mixed methodology in the validation process for instruments that measure phenomena in the field of health are makes it possible to reduce the intrinsic deficiencies of each one, quantitative or qualitative. The non-literal semantic translation-retranslation method is described in the literature as the most suitable for the transcultural adaptation of instruments. Mixed methodology is an effective approach to improve semantic adaptation and increase the terminological precision of the scale. This mixed approach in determining comfort scale content validity added to its richness, giving rise to greater semantic precision and increasing the evaluative sensitivity of the validated instrument. This is because combining both procedures made it possible to improve comprehension of the comfort construct as well as some items, taking into account the opinions of individuals involved in measures that promote the comfort of paediatric patients.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments in human beings or animals were carried out for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that this paper contains no patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that this paper contains no patient data.

FinancingThis study is a part of the project “Identification of the comfort needs of critical paediatric patients” (PR-009/16) funded by the Fundación Enfermería y Sociedad (Colegio Oficial de Enfermeras y Enfermeros de Barcelona) in the 2016 official announcement of Research Grants.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Bosch-Alcaraz A, Jordan-Garcia I, Alcolea-Monge S, Fernández-Lorenzo R, Carrasquer-Feixa E, Ferrer-Orona M, et al. Validez de contenido de una escala de confort crítico pediátrico mediante una metodología mixta. Enferm Intensiva. 2018;29:21–31.