The main aim of this investigation was to analyse the specificity and sensibility of the COMFORT Behaviour Scale (CBS-S) in assessing grade of pain, sedation, and withdrawal syndrome in paediatric critical care patients.

MethodAn observational, analytical, cross-sectional and multicentre study conducted in Level III Intensive Care Areas of 5 children's university hospitals. Grade of sedation was assessed using the Spanish version of the CBS-S and the Bispectral Index on sedation, once per shift over one day. Grade of withdrawal was determined using the CBS-S and the Withdrawal Assessment Tool-1, once per shift over three days.

ResultsA total of 261 critically ill paediatric patients with a median age of 5.07 years (P25:0.9-P75:11.7) were included in this study. In terms of the predictive capacity of the CBS-S, it obtained a Receiver Operation Curve of .84 (sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 76%) in relation to pain; .62 (sensitivity of 21% and specificity of 78%) in relation to sedation grade, and .73% (sensitivity of 40% and specificity of 74%) in determining withdrawal syndrome.

ConclusionsThe Spanish version of the COMFORT Behaviour Scale could be a useful, sensible and easy scale to assess the degree of pain, sedation and pharmacological withdrawal of critically ill paediatric patients.

El objetivo principal de la investigación fue analizar la especificidad y sensibilidad de la escala COMFORT Behavior Scale-Versión española (CBS-ES) en la determinación del grado de dolor, sedación y síndrome de abstinencia.

MétodoSe llevó a cabo un estudio observacional, analítico y transversal y multicéntrico en unidades de cuidados intensivos pediátricas de 5 hospitales españoles. Se valoró el grado de sedación del paciente crítico pediátrico de forma simultánea empleando para ello la CBS-ES y registrando los valores del Bispectral Index Sedation, una vez por turno durante un día. El grado de abstinencia se determinó una vez por turno, durante 3 días, empleando de forma simultánea la CBS-ES y la Withdrawal Assessment Tool-1.

ResultadosSe incluyeron en el estudio un total de 261 pacientes críticos pediátricos con una mediana de 1,61 años (P25: 0,35-P75: 6,55). Por lo que a la capacidad predictiva de la CBS-ES se refiere se obtuvo un área bajo la curva de 0,84 (sensibilidad del 81% y especificidad del 76%) con relación al dolor; de 0,62 (sensibilidad del 27% y especificidad del 78%) en el caso de la sedación, y de 0,73 (sensibilidad del 40% y especificidad del 74%) en el del síndrome de abstinencia.

ConclusionesSe ha podido contrastar que la CBS-ES podría ser un instrumento sensible, útil y fácil de emplear para valorar el grado de dolor, sedación y síndrome de abstinencia farmacológico del paciente crítico pediátrico.

What is known?

The COMFORT Behaviour Scale-Spanish version (CBS-ES) is a valid and reliable instrument for the determination of the degree of discomfort of critical paediatric patients.

What does this paper contribute?

Although several instruments are available to evaluate the degree of sedation, analgesia and withdrawal syndrome in critical paediatric patients, no validity and reliability studies are available in the Spanish state that recommend a specific evaluation scale. This fact sometimes leads to undervaluation. The study presented here shows that the CBS-ES may be a valid, useful and easy-to-use instrument for assessing the degree of sedation, analgesia and pharmacological withdrawal syndrome in critical paediatric patients.

Implications of the study

Everyday clinical practice shows that using different scales simultaneously sometimes leads to a lack of systematization when assessing the degree of sedation, analgesia and withdrawal. This study may therefore encourage undertaking more studies of the clinical efficacy of the CBS-ES during the management of sedation, analgesia and withdrawal in paediatric patients admitted to a paediatric intensive care unit.

The clinical management of critically ill children is usually invasive, due to the many traumatic procedures which are necessary to aid the resolution of a pathology. All of this may cause them to suffer pain, fear, anxiety and/or stress.1–3 The latter is a factor that has a considerable impact on the patient’s recovery of health, given the consequences of prolonged stress which may arise in the organism of a critically ill child.4

Controlling the pain of a critical patient who is admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) is one of the chief priorities which all medical professionals have to take into account,5 given that the majority of the patients admitted to these units suffer pain during their stay.6 The degree of pain should therefore be monitored and assessed from the moment a patient is admitted to a paediatric ICU (PICU). Appropriate pain management may reduce or eliminate the use of sedative drugs, so that these should only be administered to ensure that the patient suffers no pain.7

According to the Spanish Society of Paediatric Intensive Care (SECIP), the use of analgesia is useful because it reduces or eliminates “the perception of pain in the presence of stimuli that normally cause it, but without the intention of producing sedation, which if it occurs will be a side effect of the analgesic medication”. 8 In connection with sedation, the same scientific body defines it as “reducing awareness of the surroundings”, establishing degrees of conscious or mild (when the patient reacts to stimuli) and deep of hypnosis.8

Although several factors may influence the degree to which critical paediatric patients are comfortable,5,6 such as their sociodemographic and clinical characteristics or those associated with the context of PICU,7 appropriate analgesia and sedation influence the prognosis of these patients, reducing morbidity and the length of admission to the said units.5 This study will therefore associate the concept of comfort with the appropriate or inappropriate use of analgesia and sedation.

The increasing use of analgesics and sedatives has also led to an increase in their side effects, such as withdrawal syndrome. This syndrome is associated with a swift or sudden withdrawal of an analgesic or sedative drug, which indirectly increases stress, interferes with respiratory weaning, complicates the evolution of the patient and prolongs their stay in the PICU. Opiates and benzodiazepines are the drugs that cause withdrawal syndrome the most often, because they are now the most widely used drugs in critical care units.9,10 A study in 2013 by Fernández-Carrión et al. therefore estimated that the incidence of this syndrome affected 50% of the patients studied.11

Due to the reasons described above, continuous daily evaluation of the degree of analgesia and sedation in critical patients using valid scales is recommended.12 There are several specific instruments for the determination, evaluation and quantification of the degree of sedation. These instruments include the Motor Activity Assessment Scale (MAAS), the Sedation-Agitation Scale or SAS, the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale or RASS13, and the Ramsay and COMFORT scales.14,15 A study by Mencía et al. shows that the Ramsay and COMFORT scales were used in 90% of the PICU analysed.16 However, it is also important to underline that several studies have covered the usefulness of non-invasive monitoring using the Bispectral Index Sedation (BIS) to evaluate the same.16–21 Although the results of Mencía et al.16 indicate that the BIS is used in up to 71% of the Spanish PICU analysed, the results of other studies vary in terms of its efficacy, although these results are considered acceptable, especially in patients who were given muscle relaxants.17–21 In spite of the proven utility of the BIS sensor in intensive care, it is important to bear in mind that to date, no evidence has been found regarding which values are associated with the best clinical results in paediatric medicine. It is therefore essential to compare the values obtained with other clinical data in neurocritical or epileptic patients without neuromuscular blockage, as well as others whose treatment may interfere with reception of the BIS signal (electromyography, hypothermia or other machines used in the PICU, etc.).

Regarding withdrawal syndrome determination, the Withdrawal Assessment Tool-1 (WAT-1)9 is used in clinical practice. It has been shown to have a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 88%.22,23

The fact that although several instruments are available, there are no Spanish validity and reliability studies which recommend a specific scale for evaluating levels of pain, sedation and withdrawal in critical paediatric patients means that sometimes these are undervalued. Due to this, a study was designed with the general aim of analysing the specificity and sensitivity of the Spanish version of the COMFORT Behaviour Scale (CBS-ES)3 in determining pain level, degree of sedation and pharmacological withdrawal syndrome in 5 PICU within Spanish territory. The specific study objectives were to (1) determine the relationship between degree of comfort and pain, the degree of sedation and the pharmacological withdrawal syndrome in critical paediatric patients; (2) to analyse the differences in the degree of comfort, pain, sedation and pharmacological withdrawal in the morning and night shifts, and (3) to determine the minimum time required by critical care professional to administer the CBS-ES.

Material and methodsDesignThis study is observational, analytical, transversal and multicentre.

Study population and areaNon-probabilistic consecutive sampling was used to include patients aged from 7 days to 18 years old who were admitted to any of the PICU taking part with an indication of mechanical ventilation and the continuous administration of analgesia and sedation during at least 5 days, and fitted with a BIS brain monitor sensor. Terminal paediatric patients were excluded, as were those for whom there was a language barrier.

The study was undertaken in the PICU of 5 hospitals in a total of 3 autonomous communities within Spanish territory, from May 2018 to January 2020.

Approval was obtained from Ethics and Clinical Research Committee of the hospital which coordinated the study as well as those of the 4 collaborating hospitals. The patients or their legal tutors gave their verbal and written consent.

Variables and instrumentsThe main or result variable was the specificity and sensitivity of the CBS-ES to detect the absence of comfort in situations associated with pain, the degree of sedation and pharmacological withdrawal.

To record the result variable the CBS-ES with a Cronbach alpha of 0.71 was used. This is composed of 3 dimensions, each one of which has 2 factors: (1) “Alert and Physical Movement”; (2) “Calm/Agitation” and “Respiratory Response/Flat”, and (3) “Muscle Tone” and “Facial Tension”. After assigning a score from 1 to 5 to each item, this states that values < 10 points indicate that the patient has no absence of comfort, from 11-22 they suffer absence of comfort, and at scores > 23 points the child is suffering severe absence of comfort.3

The following age-adapted pain evaluation scales were used to assess the pain of critical paediatric patients: PAIN (< 1 month of life), FLACC (> 1 month, up to 4 years and patients who do not collaborate), faces scale (> 4 years) and the numerical scale (> 8 years). These instruments also classify pain using a Likert-type scale in: no pain (0 points), mild pain (1-3 points); moderate pain (4-7) and severe pain (8-10 points).24–27

Another instrument used was the BIS, which uses a sensor placed on the patient’s forehead to measure the degree to which they are sedated. The scores obtained by the BIS classify patients as: not sedated (scores from 81-100); moderately sedated (scores from 61-80); deeply sedated (scores from 40-60); very deeply sedated (scores ≤ 40) and electroencephalographic suppression (a score of 0). Determinations were undertaken after verifying that the Sensor Signal Quality Index was ≥ 95%. If this value was not attained, then the sensor was checked to ensure that it was correctly in position or replaced, if necessary.28

The WAT-1 scale was used to evaluate the withdrawal syndrome. This determines 11 symptoms in several time bands, including the presence of fever, gastrointestinal symptoms, sweating, patient response to stimuli, movements and muscle tone. A Likert-type scale is used to obtain a score of from 0 to 12 points, establishing the presence of the withdrawal syndrome when scores are ≥ 3.9,10

No transcultural adaptation and validation studies were found for the said instruments (pain scales, BIS and WAT-1) in the Spanish population. Nevertheless, they have been recommended and supported by clinical practice and the SECIP, after having been widely used during the clinical management of critical paediatric patients.9,10

The following sociodemographic and clinical factors were taken into account as secondary variables: age (in years), sex, underlying pathology, reason for admission to the PICU, devices used in the patient, type of analgesia and sedation administered and length of stay in the PICU (in days). The professional who evaluated the degree of analgesia and sedation was identified, together with how many years’ experience they had and, in the case of the CBS-ES, the minimum time taken by professionals to complete it was established. An ad hoc data recording notebook was designed for these data, the content of which was approved by the whole research team in the 5 hospitals involved. These data included the informed consent, all of the sociodemographic and clinical variables studied, and the 3 evaluation instruments to be used.

Data gatheringWhen a patient was admitted who fulfilled the selection criteria, their legal tutors were requested to give their written and verbal informed consent. Once this had been obtained, the researcher recorded the patient’s sociodemographic and clinical data in the data recording notebook. Prior to this process, the researchers had received specific training, consisting of a detailed explanation of the project, its objectives, the data gathering procedure and the instruments to be used.

The degree of pain suffered by critical paediatric patients was measured in the morning and at night during the first 24 hrs. of the start of the data gathering process, using the most suitable pain scale for the patient’s age.

The degree of sedation was determined by simultaneously recording the BIS value on the monitor screen and administering the CBS-ES. These measurements were taken once per shift (morning and night) during the first 24 hrs. after admission.

Lastly, pharmacological withdrawal syndrome was recorded for those patients who had been mechanically ventilated with continuous analgesia and sedation during at least 5 days. For this their degree of withdrawal syndrome was simultaneously evaluated using the CBS-ES and the WAT-1 scale. These determinations were undertaken once per shift (morning and night) during 3 consecutive days.

Data analysisRecorded data were stored in a database created using v.23 of the IBM® SPSS statistical programme.

The sample distribution was calculated. Numerical variables were described using descriptive statistics (average, standard deviation, median or quartiles), while categorical variables are shown in frequency tables with percentages.

The ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve was calculated to determine the efficiency of a numerical variable as a predictor for another binary variable. The curve associated with specificity and sensitivity corresponding to each possible cut-off point was calculated. Values from 0.70 to 0.80 were considered acceptable. The Youden index was calculated as a specificity and sensitivity parameter, setting a score of 1 as the maximum value. The average gamma association was used to check the relationship between 2 ordinal variables.

The t-test, the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test and the Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare a numerical variable with another categorical variable, depending on their distribution. Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to establish the said relationship between 2 categorical variables.

A confidence interval of 95% was assumed in all of the tests, and data were considered to be significant when P ≤ .01.

ResultsSociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participantsA total of 261 patients were included in the study. 53.64% of the sample were children with a median age of 1.61 years (P25: 0.35-P75: 6.55). 32.95% (n = 86) of the patients had a chronic pathology, the most frequent of which was congenital cardiac pathology, in 16.09% (n = 42). The main reason for admittance was respiratory, in 36.78% (n = 96), followed by postoperative care in 26.82% (n = 70).

The most common device used was a peripheral venous catheter (76.25%, n = 199 patients). 55.56% of the patients were on mechanical ventilation and 70.11% were given continuous analgesia and sedation, with Midazolam® (40.23%, n = 105) as the most widely used drug. The median stay of patients in the PICU during the study was 5 days (P25: 2-P75: 12). Table 1 shows all of the data deriving from the sociodemographic and clinical variables that were recorded.

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of the sample (n = 261).

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Duration of admission (days)a | 5 (2-12) |

| Sex (n/%)b | |

| Female | 121(46.4) |

| Male | 140(53.6) |

| Age (years)a | 1.61 (0.3-6.5) |

| Reason for admissionb | |

| Respiratory | 96 (36.8) |

| Postoperative care | 70 (26.8) |

| Infection | 23 (8.8) |

| Oncological | 14 (5.4) |

| Others: invasive procedures | 58 (22.2) |

| Chronic pathology (n/%)b | |

| Yes | 86 (32.9%) |

| No | 175 (67.1%) |

| Type of chronic pathologyb | |

| Congenital cardiac pathology | 42 (16.1%) |

| Neuromuscular | 13 (5%) |

| Down syndrome | 7 (2.7%) |

| Respiratory | 7 (2.7%) |

| Metabolic | 7 (2.7%) |

| Renal | 6 (2.3%) |

| Neurological | 2 (0.8%) |

| Immunodeficiency | 1 (0.4%) |

| Losses | 1 (0.4%) |

| Mechanical ventilationb | |

| Yes | 145 (55.6%) |

| No | 116 (44.4%) |

| Sedation and analgesiab | |

| Yes | 183 (70.1% |

| No | 78 (28.9%) |

| Type of sedation and analgesiab,c | |

| Midazolam | 105 (40.2%) |

| Methadone | 95 (36.4%) |

| Fentanyl | 42 (16.1%) |

| Diazepam | 36 (13.8%) |

| Levomepromazine | 19 (7.3%) |

| Clonidine | 18 (7%) |

| Remifentanil | 15 (5.7%) |

| Morphine hydrochloride | 15 (5.7%) |

| Chloral hydrate | 13 (5%) |

| Dexmedetomidine | 12 (4.6%) |

| Propofol | 4 (2.9%) |

| Chlorpromazine | 13 (5%) |

| Others | 17 (6.5%) |

| Devices fitted to patientb,d | |

| Peripheral venous catheter | 199 (76.2%) |

| Central venous catheter | 162 (62.1%) |

| Bladder catheter | 129 (49.4%) |

| Nasogastric catheter | 111 (42.5%) |

| Arterial catheter | 100 (38.3%) |

| Oxygen therapy | 41 (15.7%) |

| Pericardial drain | 32 (12.3%) |

| Pleural drain | 30 (11.5%) |

| Non-invasive ventilation | 26 (10%) |

| External ventricular shunt | 13 (5%) |

| Peritoneal drain | 8 (3.1%) |

| Jackson Pratt drain | 8 (3.1%) |

Data were gathered by a total of 17 professionals (13 nurses and 4 intensive care doctors). In 70.85% (n = 205) of cases the scales were administered by critical care nurses who had an average of 12.42 ± 4.68 years of experience. The average median time taken by the professionals to administer the CBS-ES was 2 min. (P25: 0.5-P75: 3).

Degrees of the absence of comfort, pain, sedation and withdrawal syndrome60.54% (n = 158) of the patients in the day shift had no absence of comfort (scores ≤ 10 in the CBS-ES) versus 69.35% (n = 181) of the patients in the night shift, followed by 36.40% (n = 95) during the day and 27.59% (n = 72) at night who suffered the absence of comfort (scores from 11-22 in the CBS-ES).

93.85% (n = 245) of the patients analysed in the morning shift and 94.64% (n = 247) of those analysed in the night shift suffered no pain.

The average BIS value obtained was 51.31 ± 15.02 points during the day versus 50.86 ± 15.57 at night. The levels of absence of comfort and the degree of sedation were found to be statistically significant when they were analysed, in the day shift (P = .022) as well as the night shift (P = .012). Greater sedation is therefore associated with less absence of comfort.

The median of the scores for withdrawal syndrome was 1.54 (P25: 0-P75: 3) points during the day versus 1.59 (P25: 0-P75: 3) at night. When these data are broken down according to days of evaluation, a median of 1 point (P25: 0-P75:3) was found on the first day; 1 point (P25: 0-P75: 3) on the second day, and 0 points (P25: 0-P75: 2.25) during the third day. The relationship between absence of comfort detected by the CBS-ES and withdrawal syndrome was found to be statistically significant during the morning shift (P < .001) and in the night shift (P < .001). A greater absence of comfort is therefore associated with a higher presence of pharmacological withdrawal syndrome.

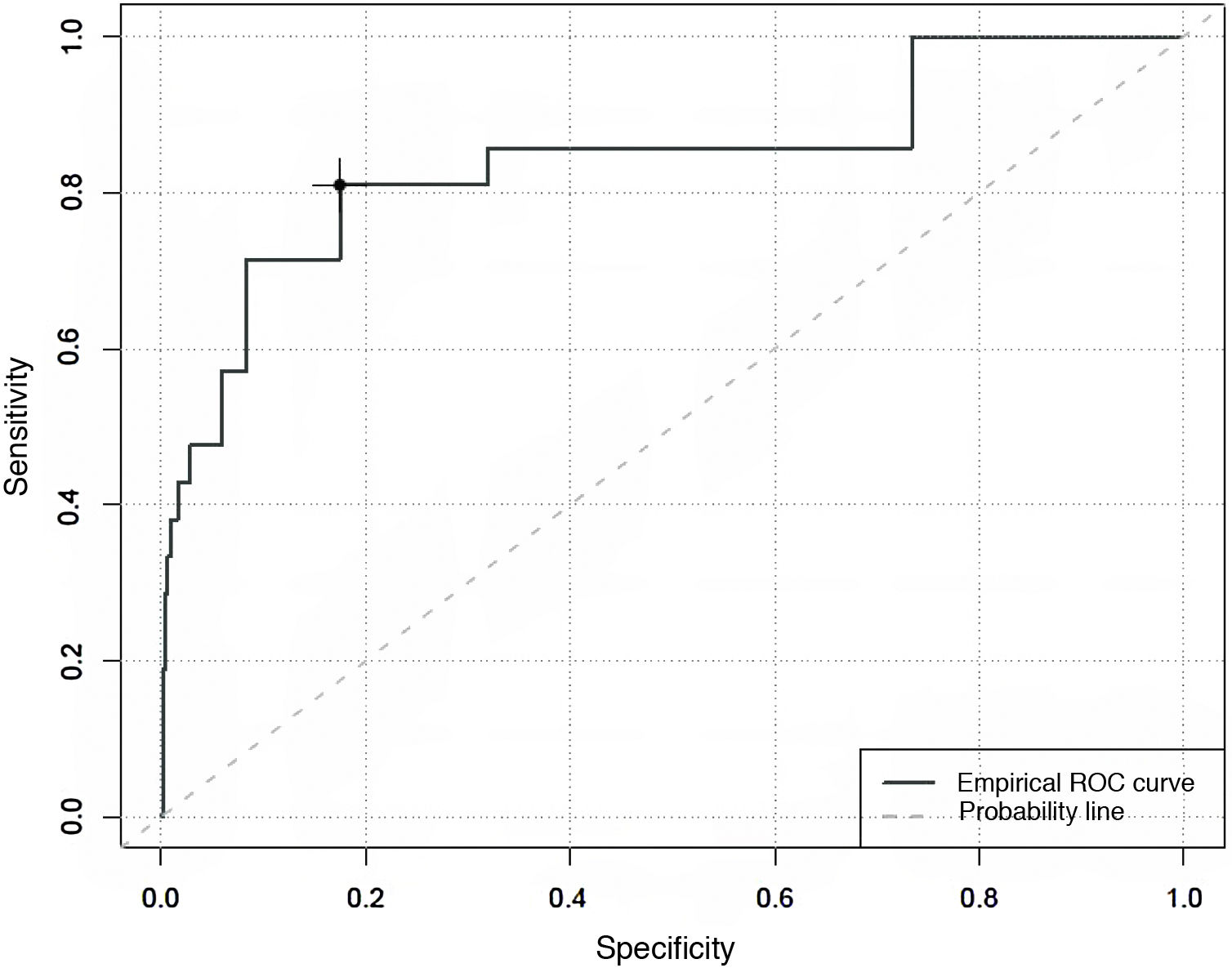

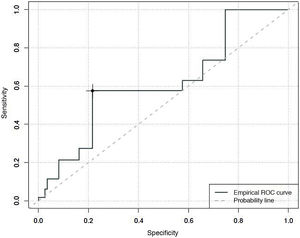

Specificity and sensitivity of the COMFORT Behaviour Scale-Spanish version, in evaluating the degree of analgesia, sedation and withdrawal syndromeWhen the predictive capacity of the CBS-ES to detect situations of an absence of comfort associated with pain, an area under the curve of 0.84 was found, with a maximum Youden index of 13. This estimates that over 13 points the CBS-ES has a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 76% in the detection of situations where the absence of comfort is associated with pain (Fig. 1).

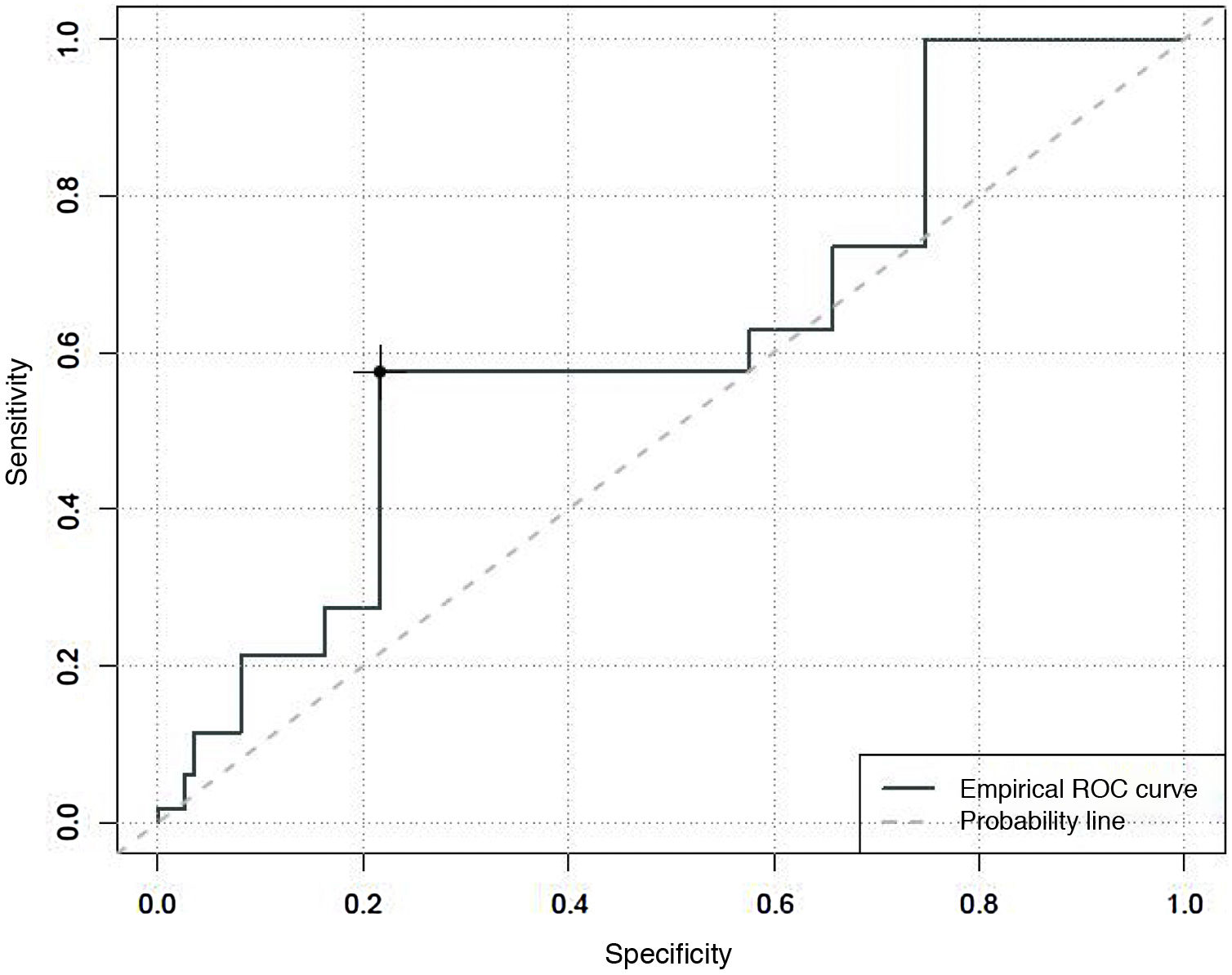

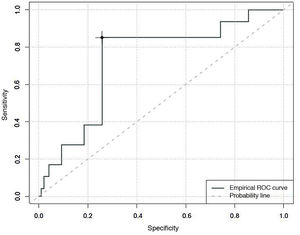

An area under the curve of 0.62 was found for degree of sedation, with a Youden index that classified patients as unsedated, with a sensitivity of 27% and a specificity of 78%, with CBS-ES scores equal to or higher than 10 (Fig. 2).

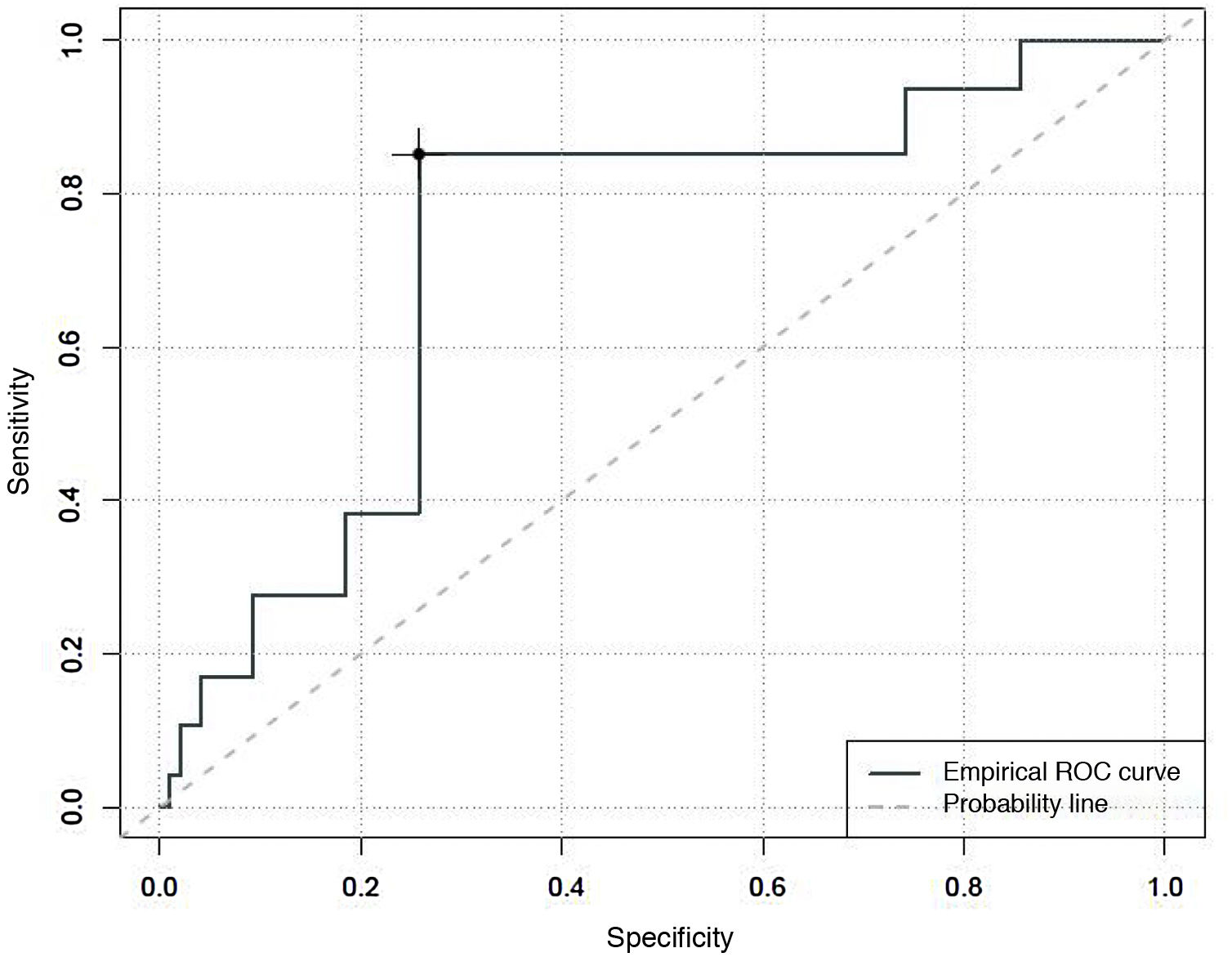

Finally, an area under the curve of 0.73 was found when determining the predictive capacity of the CBS-ES to detect situations in which the absence of comfort is associated with withdrawal syndrome. The Youden index estimated that scores of 10 in the CBS-ES would correspond to situations of withdrawal syndrome, with a sensitivity of 40% and a specificity of 74% (Fig. 3).

When the scores obtained after using the CBS-ES and the BIS to simultaneously evaluate the degree to which critical paediatric patients were sedated, gamma indexes were obtained of −0.618 (P = .022) during the day and −0.663 (P = .012) at night, so that increased absence of comfort coincides with less sedation.

After comparing the CBS-ES and WAT-1, a direct and significant association was detected between both instruments in all of the shifts and days evaluated: day 1 morning (γ = 0.859, P < .001) and night (γ = 0.939, P < .001); day 2 morning (γ = 0.838; P < .001) and night (γ = 0.93, P < .001) and day 3 morning (γ = 0.888, P < .001) and night (γ = 1, P < .001). Therefore, increased absence of comfort is associated with a greater withdrawal syndrome.

DiscussionThe majority of the patients included in the study were comfortable (CBS-ES scores ≤ 10 points). More than 90% were found to have no pain, with an appropriate control of their degree of sedation (BIS scores of 51.31 ± 15.02 during the day versus 50.86 ± 15.57 at night). Moreover, low levels of withdrawal syndrome were detected (WAT-1 < 3 points).

It is important to take these aspects into consideration as the clinical management of patients admitted to the PICU requires an exhaustive control of their degree of pain, sedation and withdrawal, to prevent over-sedation.29 The results of this study therefore make it possible to conclude that this control is being appropriately implemented in the PICU analysed.

The COMFORT Behaviour Scale was the main instrument used, as it is the only scale found to date which has been transculturally adapted and validated in the Spanish paediatric population.3 It is also important to underline that a systematic review prepared by Dorfman et al.30 found the COMFORT Behaviour Scale31 to be both valid and reliable when evaluating the degree of pain and sedation in critical paediatric patients, so that it was the scale which best fitted the set objectives. Even so, lower scores were obtained in the CBS-ES for sensitivity and specificity in the detection of situations involving absence of comfort associated with pain and degree of sedation than was the case with the original scale. While this study found sensitivity and specificity data of 81% and 76% in connection with pain, and 27% and 78% in connection with degree of sedation, in the original scale figures were obtained in the intervention group of 82% for sensitivity and 92% for specificity.30

The predictive power of the CBS-ES has been verified in the determination of situations of absence of comfort associated with pain. It is therefore possible to state that scores ≥ 11 in the CBS-ES and the presence of mild pain after measuring this on an age-adapted scale require revision of the analgesic regime. These data contrast with those of the study by Van dijk et al.,31 which indicates that values of 17 in the COMFORT scale and 4 in the pain scale require modification of the analgesic regime. Additionally, a study by Boerlage et al. estimated that the minimum time necessary for a PICU medical professional to administer the COMFORT Behaviour Scale was 2 min.32 This agrees with the findings of the study presented here, which found that the optimum average time to administer the CBS-ES is 2 min. (P25: 0.5-P75: 3).

It is important to take these cut-off points into consideration, because although research into pain control and management in critical patients has progressed, several studies show that it is still one of the most common problems in ICUs.33–36 Some studies indicate that more than 50% of the adult patients admitted to an ICU suffer pain due to their clinical management (devices, immobility and routine nursing care such as oral hygiene), as well as the diagnostic and therapeutic procedures they are subjected to during medical care.34,37–40

The degrees of critical paediatric patient sedation measured using the BIS sensor were appropriate (51.31 ± 15.02 points during the day versus 50.86 ± 15.57 at night). They were similar to those found by another study,41 which obtained values of 52 (0-98).

Finally, average scores for pharmacological withdrawal syndrome were found to be 1.54 (P25: 0-P75: 3) points during the day versus 1.59 (P25:0-P75:3) at night. These are similar to the values found in the study by Conrad et al., which found that 15% of the patients obtained scores of 1-2 in the WAT-1 and 31.7% scored 3-8 points.23

LimitationsThe chief limitation of this study centres on selection and information bias, as well as the observer bias deriving from the design and type of sampling.

ConclusionsThe CBS-ES is a specific instrument for measuring pain, sedation and pharmacological withdrawal syndrome in critical paediatric patients. Nevertheless, its sensitivity should be studied in depth when it is used to determine degree of sedation and withdrawal syndrome.

Future studies should focus on establishing specific analgesia and sedation protocols that are guided by instruments with appropriate metric properties, such as the CBS-ES. This would allow the medical professionals who work in PICUs to improve their monitoring of the degree of analgesia and sedation, personalizing pharmacological therapy and the doses given even more, as this may prevent, reduce and even avoid the pharmacological withdrawal syndrome.

FinancingThis study received no financing from any type of body or private company.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank the whole research team for their enthusiasm and help during the entire data gathering process, together with the paediatric patients and their families who accepted taking part in the study.

Please cite this article as: Bosch-Alcaraz A, Tamame-San Antonio M, Luna-Castaño P, Garcia-Soler P, Falcó Pegueroles A, Alcolea-Monge S, et al. Especificidad y sensibilidad de la COMFORT Behavior Scale-Versión española para valorar el dolor, el grado de sedación y síndrome de abstinencia en el paciente crítico pediátrico. Estudio multicéntrico COSAIP (Fase 1). Enferm Intensiva. 2022;33:58–66.