The nursing profession, without losing its essence, is in continuous evolution in order to face and respond to the ever-changing health challenges of the population. Advanced Practice Nursing is a clear example of this development. The performance of advanced practice roles entails greater responsibility, expansion and depth of nursing practice, which is only possible with additional education beyond the bachelor's degree – a master's or doctoral degree in nursing – and greater expertise in clinical practice in a particular area of specialization.

Advanced practice nursing is intrinsically linked to the level of education since, further academic development of nursing promotes the advancement of autonomous practice. This article addresses the education of Advanced Practice Nurses, and focuses on its core aspects; providing detailed information on competencies, curricular structure, curriculum and key components of training programs. Finally, special mention is made of advanced role training in the critical care setting.

La profesión de enfermería, sin perder su esencia, está en continua evolución para poder afrontar y responder a los retos de salud de la población, en constante cambio. La Enfermería de Práctica Avanzada es un claro ejemplo de este desarrollo. El desempeño de roles avanzados conlleva una mayor responsabilidad, expansión y profundidad de la práctica enfermera, lo cual solo es posible con una formación adicional al grado- un máster o doctorado en enfermería- y una mayor pericia en la práctica clínica, en un área de especialización concreta.

La Enfermería de Práctica Avanzada esta intrínsecamente ligada al nivel de educación, es decir, un mayor desarrollo académico de la Enfermería, promueve el avance de una práctica autónoma.

Este artículo aborda la formación de la Enfermeras de Práctica Avanzada, y se centra en sus aspectos nucleares; proporcionando información detallada sobre las competencias, la estructura curricular, el plan de estudios y los componentes claves de los programas de formación. Finalmente, se hace una mención especial a la formación de roles avanzados en el ámbito de los cuidados críticos.

It is clear that, throughout history, the nursing profession has constantly evolved to address the population’s health challenges. A clear example of this development is the Advanced Practice Nurse (APN), a concept which arose as result of a series of converging needs with regard to the population (chronicity, ageing), the health system (technological progress, shortage of doctors), together with developments in the training of the nursing profession.1

Several authors have pointed out that Advanced Practice Nursing, as distinct from generalist and specialist practice, is characterized by the combination of the nurse's values, principles and experience, together with advanced knowledge, clinical judgement, decision-making capabilities, skilled and autonomous care, and research.2,3

The APN’s role entails a higher level of responsibility, breadth and depth of practice, which is only possible – according to the International Council of Nurses – with additional training (a master’s degree or doctorate in Nursing) and greater expertise in clinical practice, in at least one specialized area.4

It is clear, therefore, that Advanced Practice Nursing is intrinsically linked to educational level, i.e. the nurses’ higher academic training helps to further advanced autonomous practice. This is supported by a comparison with the APN in the United States and Canada – where a lengthy history has led to maturity5 – with incipient development of the role in most European countries, including Spain.

In recent decades, APNs have grown in number and skills worldwide, and are a highly valued and integral part of healthcare,6 with a positive impact on health outcomes.6,7 Consequently, this professional level warrants regulation based on its essential elements: licensure, accreditation, certification and education (LACE). The LACE model is endorsed and promoted by a number of nursing organizations, including the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), which has been a key voice in defining standards for APN education, and the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN), which works on legislating and regulating nursing practice. These organizations strive to ensure that APNs are properly prepared so that they can provide safe, effective and high-quality care to the population.8

A cornerstone of the LACE model is the education which nurses receive, which must guarantee the safety and quality of the care provided by this professional profile. If they are not adequately prepared for their new role, they can jeopardize, not only their own position, but the very value of Advanced Practice Nursing itself.2,9

This paper describes the key elements in the education of Advanced Practice Nurses and the characteristics that define them, based on scientific evidence, and with the aid of my experience directing postgraduate training in advanced practice over more than 15 years in the School of Nursing at the University of Navarra.

Advanced Practice Nurse rolesAPN roles are at different stages of implementation, with some countries already very advanced (United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom), while others are still at an early phase. In advanced countries, the APN has been an integral part of healthcare for decades, whereas in Europe, it is still in its infancy with barely a decade of progress.5

In the United States, the APN includes four registered roles: nurse anaesthetist, nurse midwife, clinical nurse specialist (CNS) and nurse practitioner (NP), whereas most countries have broadened two role categories: the CNS, originally associated with hospital settings, and the NP, who is linked to primary care. Over the years, the two profiles have been adapted in line with changing population health needs and they practise interchangeably in a variety of healthcare settings.10

The CNS and the NP share much in common, but the key difference is related to the legislation regulating their scope of practice. In a number of countries, NPs are characterized as professionals with a high degree of professional autonomy. Their scope of practice legally allows them to diagnose, order and interpret diagnostic tests, prescribe treatments (including drugs) and perform specific procedures. They can also conduct disease prevention and health promotion activities, follow up chronic patients, lead care coordination, be researchers, experts providing interdisciplinary advice and patient advocates; they can work alone or in coordination with medical personnel.11 The specificity of the NP role has generated a wide-ranging debate, with these profiles being singled out for their role as “substitutes”, performing the tasks of other healthcare professionals, particularly physicians, with a practice closer to the biomedical model. However, this approach, and the use of labels such as “mini-doctors”, are inappropriate.2,3 Rather, it reflects the broader role in healthcare that NPs are empowered to play, taking on some of the responsibilities that were traditionally the preserve of medical staff, but which are by no means the essence of an APN. While the authority to perform advanced tasks may be beneficial to the delivery of health services, the emphasis on tasks should not be seen as the fundamental characteristic that distinguishes Advanced Practice Nursing from generalist or specialist practice.12

For its part, the CNS role involves advanced knowledge and expertise in a specific are of the nursing discipline. Initially, this specialization is usually linked to a particular target population (paediatrics, adults) and then to a specific area of practice, a medical specialty, a disease, a health need or problem.8 These profiles practise in a wide range of healthcare settings, where their more advanced skills and competencies (leadership, education, consultation, collaboration, research) enable them to advise patients, nurses and others in complex situations, and promote and improve the quality of care by supporting evidence-based practice (EBP). The CNS provides direct patient care, but have an impact or influence at three levels: patient, nurses and nursing practice, and organizational.10

In addition, the CNS plays a “supplementary” role, taking on responsibilities for new services that cater for new needs such as the care of chronic conditions, and promoting the improvement and continuity of care. Their consultations are based on the standards of nursing theory and practice, although these more advanced profiles have greater expertise and experience in the field.2,3

The education of Advanced Practice NursesAcademic postgraduate educationThere is general international consensus that a master's level is required to prepare APN practitioners; the training includes both knowledge development and supervised practice.3 However, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) argues that the master’s level should be replaced by a Doctorate in Nursing Practice (DNP).13

Additionally, in most countries it is a basic requirement that master’s and doctoral degrees be awarded by the competent national bodies; and that the programme should be accredited and taught by universities.2,4

Why is a postgraduate degree needed?The first and most fundamental reason is that a master’s and/or doctoral degree in Nursing provide the necessary academic training to be able to practise the profession, differentiating to a greater extent between the preparation of a generalist and/or specialist nurse, and an Advanced Practice Nurse.

Further education beyond the Nursing degree and clinical expertise entail a broader and deeper approach to nursing practice, with spheres of influence beyond direct care of people which have an impact on the discipline, on professionals and on healthcare organizations.

Secondly, they enhance the image and credibility of the nurse in relation to other disciplines. And finally, postgraduate studies promote the consolidation of the research competence that is necessary for APN.2

Competency-based trainingAcademic APN programmes must be competency-based and reinforced by specialized clinical supervision, within a framework of partnership between universities and clinical areas.14

Once the functions have been identified, the next step is to develop a skill set that is taught and assessed in a sequential and progressive manner,2 which will enable the role to be performed effectively. It is important to emphasise that APN skills build on an existing base, and are additional to those of the generalist nurse and underpinned by the values, knowledge, philosophy and theories of the nursing discipline with a focus on person/family-centred care.11

There is extensive scientific literature containing detailed descriptions of APN competencies. The conceptual model developed by Hamric et al. is widely accepted by the educational and scientific community as it proposes a set of competencies that are valid regardless of the APN speciality. Hamric et al. place direct clinical practice at the centre of the nurse /patient relationship.15

Direct clinical practice, as a core competency, integrates and articulates a range of competencies, which make sense when applied in the framework of direct care: role modelling and coaching, EBP, leadership and change agent, consultation, collaboration, ethical decision making.15

Similarly, in its conceptual framework on APN, the Canadian Nurses Association (CNA) divides competencies into six categories: direct integral care, education, research, leadership, consultation and collaboration, and healthcare system optimization.

Like Hamric et al., the CNA considers APN to be founded on direct, person/family-centred care, with an integrated and holistic approach, which these nurses provide autonomously or in collaboration with other members of the healthcare team. They also endorse the development of other competencies involving direct care.11

To acquire these competencies, immersion in the clinical setting offers abundant opportunities for nurses to learn first-hand from real situations, face up to unexpected challenges, develop problem-solving skills in a dynamic context, interact with multidisciplinary teams, and gain a deep understanding of patient experiences.11,15

The curricular structure of Advanced Practice Nurse programmesTo design the curriculum of an APN master’s degree, it is important to identify the curricular objectives, the needs of the health system, and the health and education policies of the country where the programme is to be introduced.16 Taking these factors into account will keep programmes in line with the real expectations and responsibilities of this professional profile. Strategic planning, and a balance and integration of theory and practice are also important.17

The curriculum of an APN programme includes a combination of different kinds of knowledge18:

Advanced knowledge of the nursing disciplineAdvanced Practice Nursing is underpinned by values, principles, ethics and knowledge of the discipline with a focus on person/family-centred care11 in clinical practice that includes a holistic perspective, partnership with patients, and use of different approaches to their care.15

APN training programmes should provide advanced knowledge of nursing philosophy, theories and ethics, clinical judgement and decision-making skills,3 as it is the depth of the latter and the critical thinking associated with clinical reasoning that distinguishes the APN from the generalist and specialist nurse.2

It is important for the philosophy behind academic APN programmes to be based on the autonomous practice, responsibility and commitment required of the nurse. It is also crucial for the nurse to be knowledgeable about the research process and the application of EBP in the clinical setting.19

Knowledge of the advanced roleThe education of these nurses is linked to their role and the definition of their functions, and these tend to evolve simultaneously, followed by legislative regulation.5 It is important for new professionals to be prepared for the reality of clinical practice, because learning their role begins during the educational process.9

Learning about the history and definition of the APN is essential, as is a deeper understanding of the concept of the advanced role, its implementation, responsibilities and functions within the country’s healthcare system so that it can be carried out effectively and ethically. It is also advisable to compare different APN profiles (CNS, NP), and to gain a deeper understanding of direct clinical practice as the core competency of APN, which supports a further range of competencies, such as consultation, leadership, etc.2,3,9

Finally, it is crucial to address issues such as the transition process to the advanced role, and the barriers and facilitators to its implementation in health systems. Programmes promoting confident role identification, mentoring and infrastructures involved in the APN role and the field of practice will facilitate the transition from generalist to Advanced Practice Nurse.20

Specialist knowledge (in a specific clinical field)APN training is also linked to a specific expertise defined either in terms of population (e.g., adult, paediatric, etc.), by setting (e.g., Intensive Care Unit [ICU], Emergency Department), by medical specialty (e.g. oncology), or in terms of a particular problem (e.g. pain).

An in-depth knowledge of both theory and clinical practice in a specific area of specialization is required. This includes an advanced understanding of the pathophysiology, pharmacology and advanced patient assessment; of the specific nursing interventions in the field of practice, and the skills to deliver quality nursing care. The care provided by the APN includes assessment, clinical data interpretation, differential diagnosis, and decision-making.2,16

Syllabus for an Advanced Practice Nurse master’s degreeAPN training includes a syllabus in line with both the generic and the specific competencies of the specialty. Similarly, all subjects, including mentored clinical practice, are designed with a view to attaining and reinforcing the competencies required to perform the advanced role.

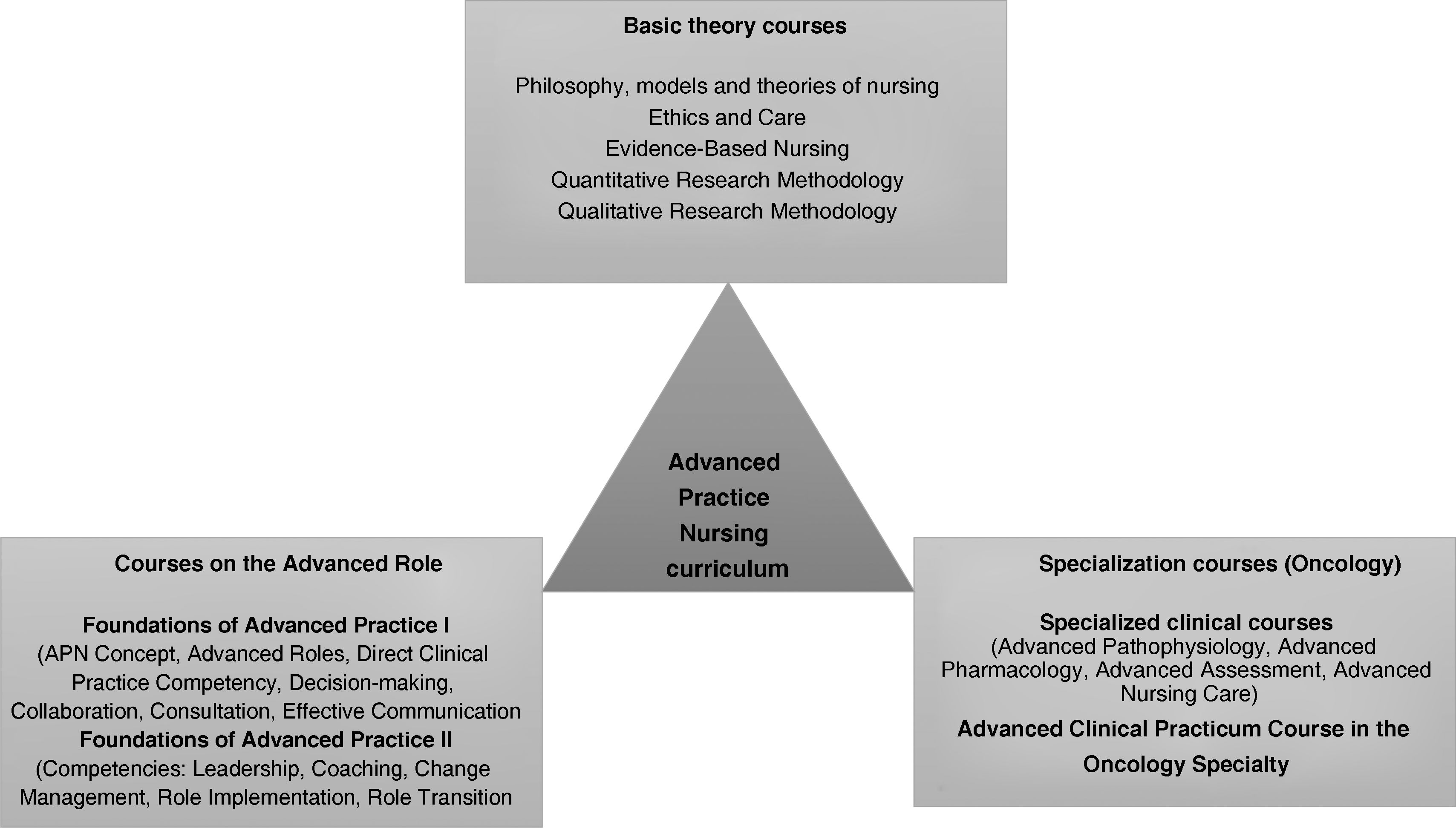

Let us consider how the curricular structure and syllabus is applied in a real-life context. The University of Navarra Master’s Degree in Advanced Practice Nursing in Oncology (MPAO) is a programme designed to train professionals who wish to perform an advanced role in the oncological speciality in the Spanish healthcare system. Fig. 1 shows all the degree courses, including the clinical practicum.

Syllabus of the Master’s Degree in Advanced Practice Nursing in Oncology (MPAO).18

The syllabus should include a clinical practicum which provides students with access to a sufficient range of clinical experiences for them to apply and consolidate, under supervision, the theoretical and practical content learned in the classroom3; to develop competencies and acquire clinical expertise in a particular specialty.2

In this regard, it is imperative to develop synergies between universities and healthcare institutions in order to select the appropriate clinical settings, where the academic vision of the advanced role matches the clinical context, ensuring that the stipulated quality standards are maintained.16 At the same time, qualified mentors must be identified to enable the student to complement their classroom training. This involves working together to develop and maintain a clinical plan, keep weekly records, and monitor the achievement of learning goals.21 Students must be incorporated into a multidisciplinary team and their placements supervised on site by professionals who are experts in the clinical field, who need to have undergone prior training as mentors, increasing their motivation to act as role models.19

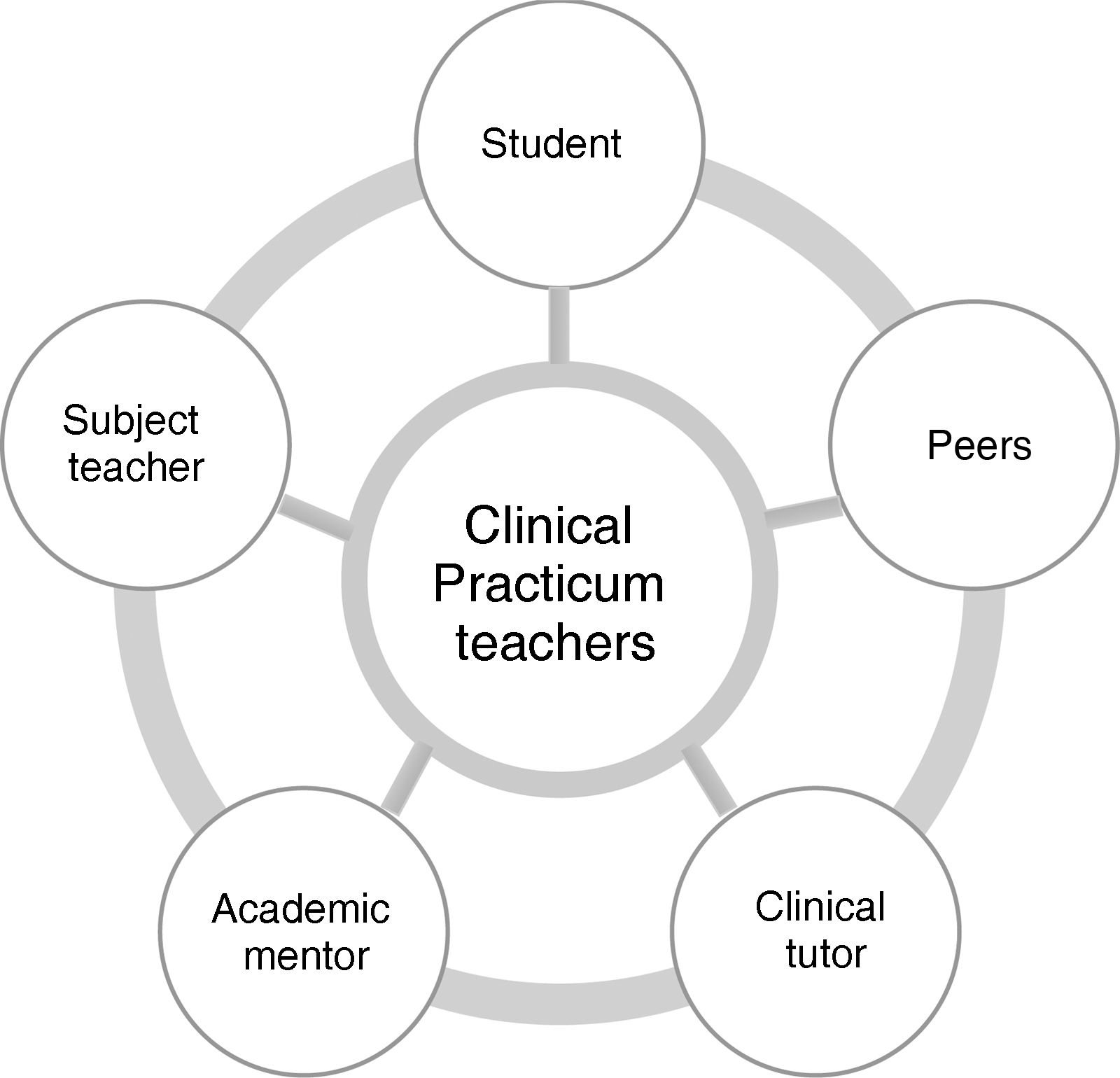

A case in point is the aforementioned Advanced Clinical Practicum, offered as a part of the University of Navarra Master’s Degree in Advanced Practice Nursing in Oncology (MPAO) where students receive an intensive practical immersion with clinical oncology experts in national healthcare facilities. The student is part of a teaching support team comprising academic mentors, clinical tutors and teachers (Fig. 2), which ensures that academic standards are maintained and that the competencies of the placement are achieved. During the early years when the MPAO was created, the team’s purpose was to mitigate the absence of oncological APN in most Spanish healthcare institutions.

A formal programme of tutorials has been designed to run throughout the practicum module,22 combining individual face-to-face mentoring (student/academic mentor and clinical tutor) with small online group tutorials (students/teachers of the practicum subject, academic mentors and clinical tutors). Additionally, as the transition from the role of generalist to APN is a stressful period, the practicum also includes a peer support network to encourage sharing of common interests and experiences in weekly group tutorials.21

Teaching and learning approachesA learner-centred approach needs to be applied in APN training programmes, providing an educational environment that encourages self-awareness, reflection, and development of the student’s true potential.19 There is an additional need for teaching and learning strategies that systematically help to enhance critical thinking and decision-making capabilities.23 These methodologies also serve to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical learning.

What learning strategies help to foster these two skills? Firstly, competency-based education, coupled with reflective practice,3,23 structured feedback from other professionals, teachers, and peers21; also mentoring programmes. Finally, simulation and/or standardized patients are increasingly recognized for their ability to enhance critical thinking and practical skills.24,25

TrainersAs in other disciplines, training to teach at university level requires a doctorate. In nursing, the shortage of teachers with a master’s or doctoral degree is an obstacle to establishing APN training programmes in universities. Similarly, in the field of clinical training, a lack of role models and mentors at the early stages in creating APN programmes at an institution is a major barrier to developing effective practice.19,26

To be able to provide quality education in APN programmes, it is therefore important to have qualified academicians and/or clinicians. 3,27 To this end, the Faculty of Nursing at the University of Navarra initiated a strategic plan to train teachers with the highest academic degrees in 1996. Of the MPAO teachers, 76% have PhDs, 45% of which are PhDs in Nursing, and 24% are clinical experts in APN.

An approach to training advanced roles in the field of critical careInternational recognition of APN now also includes the field of critical care. The increasing complexity of ICUs is transforming management of critically ill patients and requires highly specialized nursing training.28 Demand has therefore increased for APNs who specialize in critical care.29

Added to this, APN in ICUs improves quality, safety and continuity of the care provided,30 reducing mortality, length of stay, readmission rates and costs31–33; it also increases the satisfaction of both patients and care team.32 Indeed, one review found no difference between the care given by APNs and ICU physicians.34,35

APN critical care roles (APN-CC) are consolidated in the United States, unlike in Europe where the main finding of the International Nursing Advanced Competency-based Training for Intensive Care (INACTIC) project was a shortage of APN−CCs and uncertainty about this role in terms of policy, functions, education, skills and competencies.28

Although the hallmark of APN is autonomy,12 only the United Kingdom, Ireland, Finland and the Netherlands indicated that APN-CC had full autonomy to perform their role in the ICU. A number of countries have introduced advanced practice in ICUs without making legislative and regulatory changes in the scope of practice that would allow this professional autonomy; consequently, diagnosis and treatment, drug prescription and the performing of invasive procedures are considered the preserve of ICU physicians.28,29

Few studies have defined APN-CC competencies, and there is great disparity of functions in the advanced profiles in intensive care.29 Most of the competencies that have been described, both clinical and non-clinical (practice development, leadership, research and education), are generic, and only a few are specific areas of critical care.29

One study presents a competency-based curriculum for APN-CC. Created by a panel of experts, it validates nine different competencies: professional development, scientific basis, procedural skills, diagnostic studies, mechanical ventilation, complex disease management, end-of-life care, patient safety and pharmacology.14 The INACTIC project used a Delphi study to provide a set of competencies that could be the basis for an APN-CC educational programme in Europe. It presents competency in four different domains: D1) knowledge, skills and clinical performance; D2) clinical leadership, teaching and supervision; D3) personal effectiveness, and D4) safety and systems management.28,33,36

Where academic training is concerned, most European countries recommend a master's degree for the role of APN-CC. However, not all of them have developed programmes for advanced practice nursing in critical care, and there is also a lack of consistency in the curricular content of those that do exist.33,36

Given the nature of APN-CC, there is general consensus that clinical practice is the curricular heart of the programme. Clinical skills must be taught that are specific to the intensive care specialty. The APN-CC syllabus includes a series of courses as seen in Fig. 1, and in particular a specialist course on critical care.37 However, according to the literature, there is a gap between education and practice, caused by a lack of training in APN-CC education programmes. What is therefore proposed is additional training in the form of postgraduate resident programmes, which are undertaken in the first year of work in the ICU.14,38

Both the curricular structure, the syllabus, the level of trainers, and teaching and learning strategies have been described in previous sections of this paper and there is no need to elaborate on them further. However, it is important to highlight two strategies that some specific programmes for APN-CC recommend. On the one hand is the use of High-Fidelity Human Simulation Laboratories to teach critical care skills through various custom-designed scenarios; and, on the other hand, portfolios of learning experiences during the development of the clinical practicum.24,27

In conclusion, it is important to foster the notion of lifelong learning in advanced critical care practitioners, to further their professional and personal development.

What are the challenges in implementing the concept of advanced practice in Spain?The implementation of APN in Spain poses political, legislative and educational challenges.

It is essential to draft legislation that regulates the concept of advanced practice nursing, to define new profiles of advanced practice, and to regulate the process and integration of ANP in the Spanish healthcare system.

We also need to focus on the academic training of future advanced practice nurses. Regulated university education strategies should be proposed and implemented to bring about optimal development of clinical skills, knowledge and vision to perform the APN role.

Having a broader spectrum of practice, with more advanced roles, means creating a new dynamic in interdisciplinary collaboration, especially among physicians. But even more important is the coexistence and growth of nursing graduates, specialists and managers who share the same goal: caring for the person, the family and the community. Moreover, if new roles are to be implemented, a constructive dialogue needs to be initiated and consolidated among all agents: healthcare and education professionals, political decision-makers, professional associations, legal framework, health policies, etc.

Both the present and future development and implementation of Advanced Practice Nursing in the Spanish context necessarily require time for reflection and the consideration of a series of questions: What advanced practice profiles do we want? Can we implement advanced practice without having defined the different nursing profiles? Should we implement the concept of Advanced Nursing Practice without an existing legislative framework? What are requirements, training and accreditation are needed to work as an APN?

Most importantly, as a discipline and a profession, what professional project do we want for nurses in Spain?

FundingThe work involved in this paper received no funding of any kind.

Conflict of interestsThe authors hereby declare they have no conflict of interest.