Healthy people with intact cognitive functioning may also experience subjective cognitive deficits (SCD). However, no study has thoroughly explored these symptoms in healthy Spaniards. Therefore, we aimed to: (i) describe the pattern of SCD in this population, (ii) report magnitude categories of SCD, and (iii) correlate SCD with age, gender and years of education.

Methods102 healthy Spaniards (51 men) were recruited. Men and women subgroups were matched by age and years of education. SCD were evaluated using the 20-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire (PDQ-20). Magnitude categories of SCD were described as distribution-based quartiles of the total PDQ-20 score, with higher scores/quartiles indicating greater SCD. Participants with a total PDQ-20 score greater than 2 standard deviations (SD) above normal variation were considered at risk of clinically significant SCD.

ResultsMean total PDQ-20 score was 17.98 (SD=8.29), with higher scores on “Attention/Concentration” and “Retrospective Memory” subscales than on “Planning/Organization” and “Prospective Memory” subscales. Total PDQ-20 score distribution by quartile was: 0–11 (1st quartile), 12–17 (2nd quartile), 18–23 (3rd quartile) and 24–80 (4th quartile). Only 1.96% of participants were at risk of clinically significant SCD. There was a marginal trend in the association between age and “Retrospective Memory” subscale (rs=0.256; p=0.009).

ConclusionsOur findings may help health professionals interpret PDQ-20 scores more accurately in clinical settings. A total PDQ-20 score equal or greater to 35 may be a valid threshold for identifying people at risk of clinically significant SCD. Assessment of SCD may improve the ecological validity of research on human cognition.

Cognitive failures are minor errors or lapses in thinking that occur during daily living activitives.1 Common cognitive failures include forgetting what you came into the room for, where you left your mobile phone, wallet or house keys, or failing to remember an appointment. Although frustrating for most people, these symptoms are generally benign and temporary, lasting for seconds or minutes. However, some individuals tend to perceive them as more severe than they objectively are. For these people, subjective cognitive deficits (SCD) can represent a barrier to successfully carrying out daily living responsibilities.2–5

In general, it is accepted that clinical populations with neurologic (e.g. multiple sclerosis) or mental health disorders (e.g. major depression) experience greater SCD than healthy people.6,7 To assess these deficits several self-reported measures have been developed.1,6–11 The 20-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire (PDQ-20) stands out as one of the broader instruments in terms of cognitive domains evaluated, including attention, memory and executive function subscales. It was initially developed for patients with multiple sclerosis7,10 and later adapted for patients with major depression.4,11 In addition, together with its short 5-item form, it has been successfully used in these and other clinical populations of individuals with Fabry disease,12 rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus13–16 and chronic pain related disorders,17 as well as in healthy people.7,17–19

Previous studies have shown that the PDQ-20 is internally reliable, with Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.81 to 0.96.4,7,10 Its convergent validity is supported by significant correlations with other construct measures known to be associated with cognitive functioning, such as work productivity,2,3 health-related quality of life5 and other functional impairments.4,6,20 In contrast, several studies have raised questions about the relationship between PDQ-20 and performance on neuropsychological tasks,6,10,12,15,16 suggesting that this and other questionnaires designed to assess SCD might not be measuring objective cognitive deficits per se, but other factors related to the way in which individuals perceive their cognitive functioning in real-world activities.

Although most studies in patients with multiple sclerosis and major depression have focused on exploring SCD with the PDQ-20, self-perceived cognitive deficits in healthy people have received much less attention from researchers. In healthy Westerners, for example, studies agree that even those individuals with preserved cognitive functions may experience SCD.21,22 Nevertheless, cut-off scores for the magnitude of these deficits measured with the PDQ-20 have not yet been agreed upon.3,20 In addition, no study has explored in detail the pattern of SCD in healthy Spaniards with this questionnaire so far, making their results difficult to interpret in clinical settings. Old age, low educational level and female gender may be potential factors for greater SCD.23–26 However, current evidence is mixed and insufficient to draw definitive conclusions, supporting the need for more research examining SCD in healthy people.

Shedding light on the magnitude, pattern and correlates of SCD in healthy Spanish adults may contribute to a better understanding of this phenomenon in the general population, as well as to modulate the clinical picture of those individuals affected by a medical condition. Therefore, we aimed (i) to describe the pattern of SCD measured with the PDQ-20 in healthy Spaniards, (ii) to report magnitude categories of SCD by describing PDQ-20 data's distribution using tests of central tendency, and (iii) to correlate SCD with age, gender and years of education.

Materials and methodsParticipantsOne hundred and two healthy Spanish individuals were recruited among the working staff of the Parc Taulí University Hospital (Catalonia, Spain) and their relatives across four consecutive months (December 2017 to March 2018). Men (n=51) and women (n=51) subgroups were matched by age and years of education. To be eligible for the study, participants had to be between the ages of 18 and 64. They were excluded if had: (i) past or current history of an obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress-disorder, unipolar depression, bipolar disorder, psychotic spectrum disorder or autism spectrum disorder, (ii) past or current history of a neurological disease with a known impact on cognition, and (iii) past or current history of a substance abuse disorder (excluding caffeine and nicotine).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were confirmed through a semi-structured clinical interview based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition criteria (DSM-5), conducted by a psychiatrist or a neuropsychologist in a single session (20–30min duration). This session also covered the collection of socio-demographic information (age, gender, years of education and employment status) and the completion of a questionnaire of self-perceived cognitive deficits through an electronic form.

The study was designed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics Committee. Participants were informed about the characteristics of the study and accepted to participate voluntarily. Informed consent was obtained prior to study enrolment.

Assessment of self-perceived cognitive deficitsSelf-perceived cognitive deficits were evaluated using the PDQ-20,7 a structured self-reported measure of cognitive failures focused on daily living activities. Thus, it has high ecological validity for participants. It is organized in four 5-item subscales including the domains of: (i) “Attention/Concentration” (items 1, 5, 9, 13, 17), (ii) “Retrospective Memory” (items 2, 6, 10, 14, 18), (iii) “Prospective Memory” (items 3, 7, 11, 15, 19), and (iv) “Planning/Organization” (items 4, 8, 12, 16, 20). Each item asks about the frequency of an experience of cognitive failure during the last 7 days (e.g. forgetting to do things like turn off the stove or lock the door), which is rated as: never (0), rarely (1), sometimes (2), often (3), and very often (4). Total score ranges from 0 to 80, and each of the four subscales from 0 to 20. A higher score indicates greater magnitude of SCD.

Statistical analysisAll data was analyzed using IBM® SPSS® version 19 and is presented as percentages, means, standard deviations (SD) and quartiles. Continuous variables were checked for normality using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The total PDQ-20 score was normally distributed (p≥0.200), but age, years of education and the four PDQ-20 subscales did not.

Descriptive statistics were run to analyze socio-demographic data, total PDQ-20 score, its four subscales and each of the items. Currently, there are no pre-defined PDQ-20 score ranges for the magnitude of SCD in healthy people. Therefore, magnitude categories of SCD were described as distribution-based quartiles of the total PDQ-20 score, with higher quartiles indicating greater magnitude of SCD. This result was also displayed in a boxplot along with the mean score per quartile and the minimum and maximum values of the data set. Participants with a total PDQ-20 score greater than 2 SD above normal variation were considered at risk of clinically significant SCD. In this study, the pattern of SCD was described by ranking each of the PDQ-20 items from the highest to the lowest mean score.

Spearman's correlation coefficients were run to examine the relationship between age, years of education, total PDQ-20 score and its subscales. To explore possible gender-related differences in the total PDQ-20 score and its subscales, parametric t-tests and non-parametric Mann–Whitney U tests were run, as appropriate.

Statistical significance was set at p-value(α)<0.05. For multiple correlations, Bonferroni correction was applied (α=0.05/10=0.005). Similar methods have been used in previous studies, both in clinical and non-clinical samples.3,7,12,15,20,27

ResultsParticipants had a mean age of 54.49 (SD=10.05) years and 13.64 (SD=2.62) years of education. Regarding the employment status, 60.78% of the participants were working, 34.31% retired, 3.92% unemployed and 0.98% at sick leave.

Mean total PDQ-20 score was 17.98 (SD=8.29), with higher scores on the subscales of “Attention/Concentration” (mean, SD=5.78±2.77) and “Retrospective Memory” (mean, SD=4.57±2.67) than on the subscales of “Planning/Organization” (mean, SD=3.96±2.44) and “Prospective Memory” (mean, SD=3.67±2.51). No gender-related differences were found in the total PDQ-20 score or in the subscales.

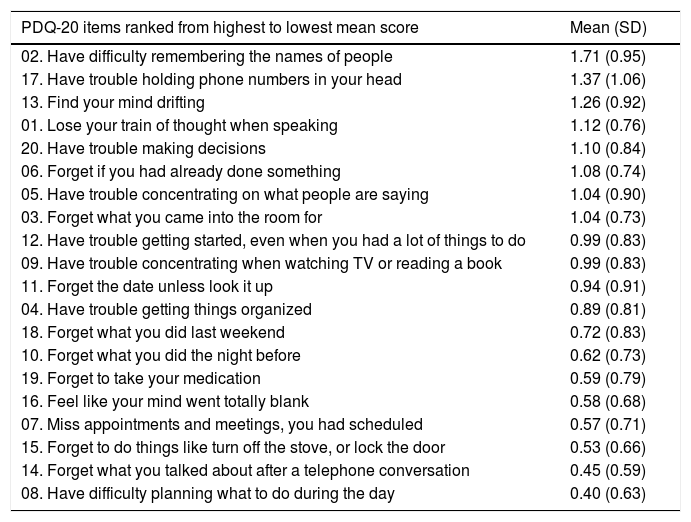

Total PDQ-20 score distribution by quartile was: 0–11 (quartile group 1: low SCD magnitude), 12–17 (quartile group 2: medium SCD magnitude), 18–23 (quartile group 3: high SCD magnitude) and 24–80 (quartile group 4: very high SCD magnitude). Fig. 1 shows a graphical representation of the total PDQ-20 score distribution along with the mean score per quartile and the minimum and maximum values of the data set. Only 1.96% of participants had a total PDQ-20 score greater than 2 SD above normal variation (PDQ-20≥35; mean, SD=17.98±8.29) and were at risk of clinically significant SCD. A detailed analysis of the SCD pattern that includes a complete list of individual PDQ-20 items ranked in order of highest to lowest mean score is presented in Table 1.

Magnitude categories of subjective cognitive deficits (SCD) presented as distribution-based quartiles of the 20-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire (PDQ-20) total score. A higher PDQ-20 score/quartile indicates greater magnitude of SCD. The median is indicated by a bold line (PDQ-20=17.5). The 25th to 75th percentiles are indicated by a box (PDQ-20=12–24). Minimum and maximum values of the data set are indicated by whiskers (PDQ-20=2–37). For each quartile group the mean score and standard deviation are presented.

Detailed pattern of subjective cognitive deficits.

| PDQ-20 items ranked from highest to lowest mean score | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| 02. Have difficulty remembering the names of people | 1.71 (0.95) |

| 17. Have trouble holding phone numbers in your head | 1.37 (1.06) |

| 13. Find your mind drifting | 1.26 (0.92) |

| 01. Lose your train of thought when speaking | 1.12 (0.76) |

| 20. Have trouble making decisions | 1.10 (0.84) |

| 06. Forget if you had already done something | 1.08 (0.74) |

| 05. Have trouble concentrating on what people are saying | 1.04 (0.90) |

| 03. Forget what you came into the room for | 1.04 (0.73) |

| 12. Have trouble getting started, even when you had a lot of things to do | 0.99 (0.83) |

| 09. Have trouble concentrating when watching TV or reading a book | 0.99 (0.83) |

| 11. Forget the date unless look it up | 0.94 (0.91) |

| 04. Have trouble getting things organized | 0.89 (0.81) |

| 18. Forget what you did last weekend | 0.72 (0.83) |

| 10. Forget what you did the night before | 0.62 (0.73) |

| 19. Forget to take your medication | 0.59 (0.79) |

| 16. Feel like your mind went totally blank | 0.58 (0.68) |

| 07. Miss appointments and meetings, you had scheduled | 0.57 (0.71) |

| 15. Forget to do things like turn off the stove, or lock the door | 0.53 (0.66) |

| 14. Forget what you talked about after a telephone conversation | 0.45 (0.59) |

| 08. Have difficulty planning what to do during the day | 0.40 (0.63) |

PDQ-20=20-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire; SD=standard deviation.

Spearman's correlation coefficients between age, years of education, total PDQ-20 score and its subscales are shown in Table 2. After applying Bonferroni correction, there was only a marginal trend in the association between age and PDQ-20 “Retrospective Memory” subscale (rs=0.256; p=0.009).

Spearman's correlation coefficients (rs) between age, years of education and PDQ-20 scores.

| Age | Years of education | |

|---|---|---|

| Total PDQ-20 score | rs=0.223 (p=0.024) | rs=−0.202 (p=0.042) |

| Attention/Concentration subscale | rs=0.187 (p=0.060) | rs=−0.153 (p=0.125) |

| Retrospective Memory subscale | rs=0.256 (p=0.009) | rs=−0.140 (p=0.161) |

| Prospective Memory subscale | rs=0.196 (p=0.049) | rs=−0.187 (p=0.060) |

| Planning/Organization subscale | rs=0.057 (p=0.570) | rs=−0.133 (p=0.182) |

PDQ-20=20-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire; Statistical significance was set at p-value (after Bonferroni correction) < 0.005.

This study contributes to a better understanding of SCD in the general population, while providing, for the first time, descriptive data on the magnitude, pattern and correlates of SCD measured with the PDQ-20 in healthy middle-aged Spanish adults. On average, the magnitude of our participants’ SCD was within the upper-limit of the 2nd quartile group (total PDQ-20 score=12–17), with greater SCD in the domains of attention and retrospective memory than in the domains of executive function and prospective memory. Less than 2% of participants were at risk of clinically significant SCD. While an older age showed a marginal positive trend towards greater SCD in retrospective memory domain, gender and educational level had no effect on SCD.

The magnitude of our participants’ SCD was similar to that of previous studies in healthy people7,17,19 and lower than that of other studies in multiple sclerosis5,27–31 and major depression,2,3,19,20,32–34 with scores falling within or above the 3rd quartile group mainly (total PDQ-20 score≥18). A detailed comparison of our participants’ SCD with that of previous studies suggests that not only the magnitude of these deficits, but also their pattern may change depending on both the presence or not of a disorder and, in case of illness, its clinical picture.6,7,28,34 Therefore, these results emphasize the importance of assessing cognitive performance from the subject's perspective, especially in those patients with a medical condition with a known impact on cognition.

At the same time, our findings are consistent with previous studies indicating that SCD are part of normal cognitive functioning unless accompanied by a medical illness.21,22 However, it is also known that people with a total PDQ-20 score greater than 2 SD above normal variation are at risk of clinically significant SCD.7,12,27 More specifically, studies have shown, also in apparently healthy individuals, that clinically significant SCD could be associated with different disorders, such as stress, a psychiatric illness or cognitive decline.1,5,21,22,36–40 In this regard, it is worth noting that 1.96% of our participants were within the range of clinically significant SCD (PDQ-20≥35).

Thus, in accordance with previous research, apparently healthy individuals exceeding the threshold for clinically significant SCD should undergo an exhaustive psychiatric and neuropsychological examination to rule out a possible disorder underlying their self-perceived cognitive deficits. Interestingly, the threshold found in our work was similar to that of the validation study in the healthy Canadian population (PDQ-20>40; SD=20±10).7 So, our results support this questionnaire as a reliable instrument for the assessment of SCD in the Spanish population.4,10,35

Finally, regarding the marginal association between an older age and greater SCD in retrospective memory domain, researchers agree that even healthy ageing is associated with a normal decline in specific types of cognitive functions, such as those involving the demand for recall,40–42 which in turn relates to previous investigations that reported greater forgetfulness over the years.36,43,44 Also, like that described in previous studies, the educational level did not appear to be related to SCD.1,23 In contrast, the greater presence of SCD observed in women in some previous investigations has not been replicated in the present work.23,24

This study is not without limitations. First, this is mostly a descriptive paper, so the presented data only intended to provide novel information on a previously unexplored area regarding SCD. Second, the study design is cross-sectional; thus, it is not possible to draw any causal conclusion on the association between age and SCD in retrospective memory domain. Third, we did no evaluate other variables known to be associated with SCD that could have helped to better describe magnitude categories, such as depressive symptomatology and/or mild cognitive impairment.21,22 Finally, the sample was limited to healthy middle-aged Spanish adults, hence, results may not be generalizable to other populations. Despite these limitations, we believe that this work provides relevant information on SCD in healthy Spaniards that may be useful in clinical and research setting as reference values for a more accurate understanding of self-perceived cognitive deficits measured with the PDQ-20.

ConclusionsSCD are a common phenomenon in healthy people, with attention and retrospective memory deficits being the most prominent. As a novelty, we provide four categories reflecting SCD magnitude that can help compare healthy and clinical Spanish individuals with regard to their total PDQ-20 score. In general, SCD in healthy people are part of normal cognitive functioning. However, a total PDQ-20 score equal or greater to 35 may indicate that the subject is at risk of clinically significant SCD. According to previous studies, clinically significant SCD could be associated with an underlying disease, such as stress, a psychiatric illness or cognitive decline. Therefore, since PDQ-20 takes less than 10min to be complete, it can be used as a screening tool to guide subsequent psychiatric and neuropsycholgical examinations, if appropiate.13,14,35 Altough SCD assessment cannot replace either medical or psychological evaluations, it can provide complementary information on how cognitive processes play out in real-life, improving the ecological validity of cognitive assessment in the laboratory or physician's office.22 Several studies have found that SCD are a good predictor of general functioning.4 However, its impact on well-being and quality of life has been almost unexplored in healthy people.

ContributorsNC designed the study and wrote the protocol. GNV, SFG and NC conducted the data collection. GNV performed the main analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. GNV, SFG, MSB, MVG, DP and NC significantly contributed to data interpretation and revised the manuscript critically. All authors approved the final version to be submitted.

FundingThe research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

We thank Dr. Goldberg and Dr. Lopez-Sola from Parc Taulí University Hospital their collaboration in the conceptualization of the study