Major psychiatric disorders require prolonged use of psychotropic medications and pose a significant economic burden. The purpose of the study is to examine the trend in outpatient utilization and public expenditures for reimbursed psychotropic medicines for major psychiatric disorders in Bulgaria from 2013 to 2017.

MethodsData on the cost and utilization of reimbursed psychotropic medications for schizophrenia and affective disorders are collected retrospectively from the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) for the period 2013–2017. The diagnostic groups included in the analysis are based on ICD codes from F20.0 to F33.4. Psychotropic drugs are systematized according to ATC code and INN. Reimbursed pharmacotherapy costs are analyzed per year and diagnosis. Drug utilization is calculated for each year in defined daily doses per 1000 inhabitants per day (DDD/1000inh/day).

ResultsThe number of patients decreased from 62 500 to 54 000, or from 834 per 1 00 000 in 2013 to 733 per 1 00 000 in 2017, or with a 3.5% decrease per year. The highest number (28,674 in 2013; 26,235 in 2017) and with the highest relative share (46%–49%) were patients with paranoid schizophrenia. The reimbursed pharmacotherapy cost showed a decreasing tendency from 35 to 31 million BGN in 2013 and 2017, respectively. In total 31 INN of medicines for psychotic disorders therapy were reimbursed. The utilization of all ATC groups is decreasing from 28.04 to 17.38 DDD/1000inh/day.

ConclusionsThe number of reimbursed patients with major psychiatric disorders, as well as the cost of pharmacotherapy and utilization of psychotropic medicines decreased in the period 2013–2017.

Major psychiatric disorders typically require prolonged use of psychotropic medications and pose a significant economic burden on societies.1 Schizophrenia and affective disorders are two of the major groups of mental disorders that have in common a chronic course, episodic nature, and remissions with varying degree of symptoms and disability.2,3 Historically dichotomized by Kraepelin, schizophrenia and affective disorders are differentiated most commonly by the prevalence of thought disturbances, disturbances of volition and first-rank symptoms in schizophrenia and predominance of mood symptoms in affective disorders.4 While depression is renowned to be the major cause of years lived in disability (YLD), the acute schizophrenic episode is the condition that has the highest disability weight (to be most closely to death) as measured by the Global Burden of Diseases.5,6

The discovery of the first-generation antipsychotics (typical antipsychotics) in the 1940s, followed by the discovery and introduction of atypical antipsychotics and antidepressants in the 1960s and 1970s has led to the possibility of deinstitutionalization of the severely mentally ill and treatment in the community.7,8 Since then, there has been a proliferation of psychotropic medications.9 Access to community-based mental health services and the affordability of psychotropic medication are now of utmost importance in the successful treatment of the mentally ill.10

Several pharmacoepidemiological studies explore the trends in the prescription and administration of psychotropic drugs.11 Report from the European Commission recommends monitoring and comparing the medicines available in the European Union, their prices, utilization, expenditure, and licensed clinical properties, as well as to compare national data with similar structure and content by using the defined daily doses and Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification (ATC)of medicines.12 The defined daily doses per 1000 inhabitants per day (DDD/1000inh/day) are widely used as a comparative measure of medicines utilization in different health care settings and across diseases.13

While expenditures for mental health in some countries increase steadily,14 in others they remain low.15 Underfunding of mental healthcare on behalf of financial institutions could be to the detriment of patients and their caregivers.16,17 Bulgaria lacks nationwide surveys on the pharmacotherapy cost and utilization of medicines for psychiatric disorders.

The purpose of the study is to analyze the trends in the public expenditures and utilization of medicines for two major psychiatric disorders – schizophrenia and affective disorders in outpatient settings in Bulgaria from 2013 to 2017.

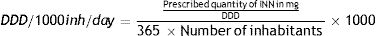

Material and methodsPublicly available data from the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) was used to gather information on the number of reimbursed patients and medications used for major psychiatric disorders in outpatient settings for the period 2013–2017. The systematization of patients was based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes - diagnoses from F20.0 to F33.4 were included in the analysis. Absolute number, relative share, and changes per year and diagnosis were analyzed. All prescribed psychotropic medicines were systematized by ATC code and International Non-proprietary Name (INN). The reimbursed cost is analyzed per year and diagnosis. The cost is presented in the national currency (BGN) at the exchange rate of 1 BGN = 0.51 Euro. Medicines utilization was calculated for every year per ATC code and INN in defined daily doses per 1000 inhabitants per day (DDD/1000inh/day) by using the following formula:

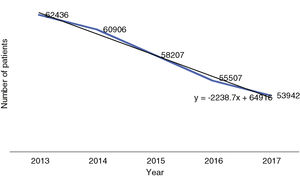

ResultsReimbursed patients with psychiatric disorders in BulgariaThe number of reimbursed patients with the selected psychiatric disorders decreased from 62 500 to 54 000 individuals with a tendency of linear decrease with approximately 2200 people per year (3.5%). The number of reimbursed patients with the investigated mental disorders was 834 per 100 000 of the population in 2013 decreasing to 733 per 100 000 in 2017. The tendency is outlined in Fig. 1.

The highest number of reimbursed patients (28 674 in 2013; 26 235 in 2017), with the highest relative share (46%–49%, respectively), have paranoid schizophrenia. It is followed by major depressive disorder, a moderate episode that accounts for nearly 25% of the reimbursed patients. Depressive disorders together from F33.0 to F33.4 account for nearly 35% of all reimbursed patients with the selected mental disorders. Patients with bipolar disorders (F31.0 to F31.7) accounting for near 17.5% of all reimbursed patients in the investigated group. Data are summarized in Table 1.

Structure of the reimbursed mental disorders.

| ICD code | Diagnosis | 2013 (n) | 2013 (%) | 2014 (n) | 2014 (%) | 2015 (n) | 2015 (%) | 2016 (n) | 2016 (%) | 2017 (n) | 2017 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F20.0 | Paranoid schizophrenia | 28 674 | 45.93 | 28 306 | 46.48 | 27 530 | 47.30 | 26 753 | 48.20 | 26 235 | 48.64 |

| F20.1 | Disorganized schizophrenia | 183 | 0.29 | 186 | 0.31 | 190 | 0.33 | 194 | 0.35 | 186 | 0.34 |

| F20.5 | Residual schizophrenia | 332 | 0.53 | 299 | 0.49 | 283 | 0.49 | 268 | 0.48 | 248 | 0.46 |

| F20.6 | Simple schizophrenia | 464 | 0.74 | 454 | 0.75 | 428 | 0.73 | 401 | 0.72 | 387 | 0.72 |

| F30.0 | Hypomania | 114 | 0.18 | 103 | 0.17 | 98 | 0.17 | 92 | 0.17 | 99 | 0.18 |

| F30.1 | Manic episode without psychotic symptoms | 46 | 0.07 | 43 | 0.07 | 39 | 0.07 | 35 | 0.06 | 41 | 0.08 |

| F31.0 | Bipolar disorder, current episode hypomanic | 1722 | 2.76 | 1588 | 2.61 | 1515 | 2.60 | 1442 | 2.60 | 1425 | 2.64 |

| F31.1 | Bipolar disorder, current episode manic without psychotic features | 1495 | 2.39 | 1409 | 2.31 | 1331 | 2.29 | 1252 | 2.26 | 1276 | 2.37 |

| F31.2 | Bipolar disorder, current episode manic severe with psychotic features | 612 | 0.98 | 580 | 0.95 | 550 | 0.94 | 520 | 0.94 | 523 | 0.97 |

| F31.3 | Bipolar disorder, current episode depressed. mild or moderate severity | 3170 | 5.08 | 3069 | 5.04 | 2873 | 4.94 | 2676 | 4.82 | 2551 | 4.73 |

| F31.4 | Bipolar disorder, current episode depressed, severe, without psychotic features | 399 | 0.64 | 377 | 0.62 | 348 | 0.60 | 320 | 0.58 | 296 | 0.55 |

| F31.5 | Bipolar disorder, current episode depressed, severe, with psychotic features | 142 | 0.23 | 122 | 0.20 | 104 | 0.18 | 86 | 0.15 | 75 | 0.14 |

| F31.6 | Bipolar disorder, current episode mixed | 2058 | 3.30 | 2077 | 3.41 | 1911 | 3.28 | 1745 | 3.14 | 1577 | 2.92 |

| F31.7 | Bipolar disorder, currently in remission | 1413 | 2.26 | 1381 | 2.27 | 1393 | 2.39 | 1406 | 2.53 | 1529 | 2.83 |

| F33.0 | Major depressive disorder, recurrent, mild | 3624 | 5.80 | 3421 | 5.62 | 3080 | 5.29 | 2739 | 4.93 | 2581 | 4.78 |

| F33.1 | Major depressive disorder, recurrent, moderate | 15 368 | 24.61 | 15 042 | 24.70 | 14 315 | 24.59 | 13 588 | 24.48 | 13 094 | 24.27 |

| F33.2 | Major depressive disorder, recurrent severe without psychotic features | 843 | 1.35 | 778 | 1.28 | 739 | 1.27 | 701 | 1.26 | 674 | 1.25 |

| F33.3 | Major depressive disorder, recurrent, severe with psychotic symptoms | 130 | 0.21 | 113 | 0.19 | 113 | 0.19 | 114 | 0.20 | 103 | 0.19 |

| F33.4 | Major depressive disorder, recurrent, in remission | 1647 | 2.64 | 1558 | 2.56 | 1368 | 2.35 | 1179 | 2.12 | 1044 | 1.94 |

For the observed period, the reimbursed cost of medicines also showed a decreasing tendency from 35 to 31 million BGN in 2013 and 2017, respectively. The cost of paranoid schizophrenia therapy is the leading one in terms of value and relative share. In 2013 it accounted for 29 million and decreased to 27 million in 2017, but its relative share as part of all expenditures showed an increase from 84% to 88%, respectively. The reimbursed cost of pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorders and depression accounted for nearly 8% for each disorder. The cost of pharmacotherapy for other disorders accounted for 5%–6% depending on the year of observation. Data are summarized in Table 2.

Reimbursed pharmacotherapy cost.

| ICD code | Diagnosis | 2013 | 2013 (%) | 2014 | 2014 (%) | 2015 | 2015 (%) | 2016 | 2016 (%) | 2017 | 2017 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGN | BGN | BGN | BGN | BGN | |||||||

| F20.0 | Paranoid schizophrenia | 29 38 2264 | 84.00 | 28 20 1170 | 85.36 | 27 80 9805 | 85.96 | 27 41 8439 | 86.57 | 27 21 8776 | 87.54 |

| F20.1 | Disorganized schizophrenia | 1 67 167 | 0.48 | 1 54 635 | 0.47 | 1 68 503 | 0.52 | 1 82 371 | 0.58 | 1 86 461 | 0.60 |

| F20.5 | Residual schizophrenia | 2 00 756 | 0.57 | 2 06 714 | 0.63 | 2 22 755 | 0.69 | 2 38 795 | 0.75 | 2 21 011 | 0.71 |

| F20.6 | Simple schizophrenia | 2 91 118 | 0.83 | 2 77 347 | 0.84 | 2 74 972 | 0.85 | 2 72 597 | 0.86 | 2 51 605 | 0.81 |

| F30.0 | Hypomania | 20 622 | 0.06 | 14 698 | 0.04 | 14 714 | 0.05 | 14 730 | 0.05 | 16 268 | 0.05 |

| F30.1 | Manic episode without psychotic sympt. | 15 652 | 0.04 | 15 828 | 0.05 | 12 124 | 0.04 | 8419 | 0.03 | 10 975 | 0.04 |

| F31.0 | Bipolar disorder, current episode hypomanic | 8 21 163 | 2.35 | 6 67 345 | 2.02 | 5 76 579 | 1.78 | 4 85 814 | 1.53 | 4 21 872 | 1.36 |

| F31.1 | Bipolar disorder, current episode manic without psychotic features | 7 16 076 | 2.05 | 6 02 750 | 1.82 | 5 16 819 | 1.60 | 4 30 889 | 1.36 | 3 92 747 | 1.26 |

| F31.2 | Bipolar disorder, current episode manic severe with psychotic features | 3 26 119 | 0.93 | 2 62 519 | 0.79 | 2 31 831 | 0.72 | 2 01 143 | 0.64 | 1 71 126 | 0.55 |

| F31.3 | Bipolar disorder, current episode depressed, mild or moderate severity | 5 65 718 | 1.62 | 3 93 793 | 1.19 | 3 58 775 | 1.11 | 3 23 757 | 1.02 | 2 87 276 | 0.92 |

| F31.4 | Bipolar disorder, current episode depressed, severe, without psychosis | 76 131 | 0.22 | 51 961 | 0.16 | 46 987 | 0.15 | 42 014 | 0.13 | 36 582 | 0.12 |

| F31.5 | Bipolar disorder, current episode depressed, severe, with psychotic features | 36 447 | 0.10 | 20 730 | 0.06 | 17 366 | 0.05 | 14 003 | 0.04 | 11 448 | 0.04 |

| F31.6 | Bipolar disorder, current episode mixed | 5 15 450 | 1.47 | 4 14 207 | 1.25 | 3 61 566 | 1.12 | 3 08 925 | 0.98 | 2 89 595 | 0.93 |

| F31.7 | Bipolar disorder, currently in remission | 3 58 891 | 1.03 | 2 74 667 | 0.83 | 3 15 776 | 0.98 | 3 56 884 | 1.13 | 3 82 745 | 1.23 |

| F33.0 | Major depressive disorder, recurrent, mild | 2 32 939 | 0.67 | 2 29 132 | 0.69 | 2 07 792 | 0.64 | 1 86 452 | 0.59 | 1 62 986 | 0.52 |

| F33.1 | Major depressive disorder, moderate | 10 98 423 | 3.14 | 11 04 318 | 3.34 | 10 74 988 | 3.32 | 10 45 659 | 3.30 | 9 17 965 | 2.95 |

| F33.2 | Major depressive disorder, recurrent severe without psychotic features | 59 132 | 0.17 | 57 409 | 0.17 | 60 854 | 0.19 | 64 299 | 0.20 | 53 695 | 0.17 |

| F33.3 | Major depressive disorder, recurrent, severe with psychotic symptoms | 9593 | 0.03 | 8233 | 0.02 | 9651 | 0.03 | 11 069 | 0.03 | 9406 | 0.03 |

| F33.4 | Major depressive disorder, in remission | 83 610 | 0.24 | 78 714 | 0.24 | 71 495 | 0.22 | 64 276 | 0.20 | 51 681 | 0.17 |

| Total (BGN) | 3 49 77 265 | 100 | 3 30 36 167 | 100 | 3 23 53 351 | 100 | 3 16 70 535 | 100 | 3 10 94 219 | 100 |

In total 31 INN of medicines, recommended for treatment of the selected psychiatric disorders, were reimbursed during the period 2013–2017. Four INNs were reimbursed only during the first 3 years of the observed period (2013–2016), namely flupentixol, alprazolam, fluoxetine, and citalopram. The utilization of all ATC groups together is decreasing from 28.04 to 17.38 DDD/1000inh/day during 2013–2017 (Table 3).

Utilisation of therapeutic groups in DDD/1000inh/day.

| ATC group | Therapeutic group | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N04BD | Monoaminooxidase inhibitors | 0.532 | 0.535 | 0.519 | 0.484 | 0.419 |

| N05AB | Phenothiazines | 0.367 | 0.452 | 0.187 | 0.014 | 0.012 |

| N05AD | Butirophenones | 0.149 | 0.172 | 0.187 | 0.021 | 0.206 |

| N05AE | Derivatives of indol | 0.097 | 0.093 | 0.080 | 0.081 | 0.078 |

| N05AF | Derivatives of thioxanten | 0.225 | 0.208 | 0.200 | 0.097 | 0.112 |

| N05AH | Diazepines. oxazapines and thiazapines | 15.780 | 13.393 | 11.729 | 10.296 | 9.957 |

| N05AL | Benzamides | 0.382 | 0.400 | 1.044 | 1.038 | 0.799 |

| N05AX | Other antipsychotics | 8.779 | 6.251 | 4.708 | 2.377 | 4.730 |

| N05BA | Benzodiazepines | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| N05BB | Derivatives of diphenilmetane | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| N06AB | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 1.173 | 1.023 | 0.963 | 0.729 | 0.761 |

| N06AX | Other antidepressants | 0.554 | 0.498 | 0.467 | 0.399 | 0.301 |

| Total | 28.039 | 23.028 | 20.086 | 15.542 | 17.380 |

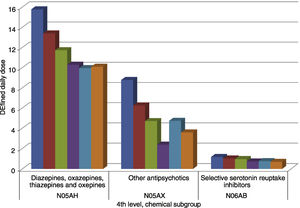

Within the therapeutic groups, a lot of variations are observed. Diazepines (N05AH), comprising of olanzapine, clozapine, quetiapine, and asenapine were the most widely prescribed with their utilization decreasing from 15.7 to 10 DDD/1000inh/day during 2013–2018, respectively. The second therapeutic group in utilization is that of other antipsychotics which include risperidone, aripiprazole, and paliperidone. It also saw a steady decrease in prescribed doses from 8.77 to 3.58 DDD/1000inh/day during 2013−2018. The same tendency was also observed for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (fluoxetine, citalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, fluvoxamine, and escitalopram) with a decrease in utilization from 1.17 to 0.69 DDD71000inh/day for the period.

In terms of INNs, the highest was the utilization of olanzapine, however, it still decreased from 13.39 to 8.75 DDD/1000inh./day during 2013–2018 years. The second product was risperidone with an extremely sharp decrease in utilization from 7.7 to 0.28 DDD/1000inh/day. Only the utilization of aripiprazole saw an increase in prescribed doses from 0.692 to 2.65 DDD/1000inh/day. The utilization of olanzapine and risperidone exhibited a sharper decrease during the observed period. All other INNs have nearly performed at a stable and low utilization rate as shown in Fig. 2.

DiscussionThe results of the study present an upsetting tendency of a decrease in the reimbursable expenditures for outpatient psychopharmacotherapy of the major types of psychiatric disorders in Bulgaria during 2013–2017. Zuvekas reported that due to rapid innovation, spending on psychotropic drugs almost tripled from $5.9 million to $14.7 million for the period 1996−2001.18 Moreover, retail sales for antidepressants grew faster than retail sales for any other therapeutic class from 2000 to 2001 in the UK.19 The use of psychotropic drugs increased with 4.7% from 1997 to 2000 for youths 17 years and younger in the USA.20 While in the majority of countries mental health expenditures increase18,20–22 and international studies have so far reported increases in health care spending with almost 58%,13 our study shows that the ambulatory cost had decreased in the 6-year observation period. This could be potentially detrimental to the care for severely mentally ill patients as recent Bulgarian studies report that the societal costs are five-to-six times higher than the healthcare cost23 and out-of-pocket costs of families are significant.17

Health care in Bulgaria is financed from obligatory and voluntary health insurance contributions and out-of-pocket payments.24 The patients’ access to reimbursed medicines paid by the public fund (National Health Insurance Fund) is ensured through a clearly defined procedure in the Law on the Medicinal Products in Human Medicine/2007, Health Law/2005 and Health Insurance Law/1999 and in the corresponding regulations. The first step of ensuring medicinal product access to the national market is obtaining the marketing authorization by the responsible drug agency following a particular procedure described in the Law on the Medicinal Products in Human Medicine/2007 or Regulation 726/2004. The procedure for price formation of every medicinal product is obligatory for the purposes of entering the national market. National Council on prices and reimbursement of medicinal products (MPs) (the Council) regulates the ceiling price of prescription medicinal products and registers the prices of over-the-counter drugs following the available regulations. The reimbursement process involves presenting evidences on efficacy, safety and pharmacoeconomic criteria. In a case of new INN, the Council should make an appraisal of Health Technology Assessment Report (HTA-report), submitted by MAH. Then the MAH should negotiate discounts with the NHIF and apply for pricing and reimbursement listing into the PDL. All procedures and deadlines are in accordance with Transparency Directive of EU. Marketing authorization holders are obliged to present evidence about the therapeutic effectiveness of medicinal products in real-life settings every three years.25 The drugs and diagnoses that are reimbursed for citizens with health insurance are included in a National Positive Drug List. The inclusion, as it is mentioned above, is based on the required legislative criteria of efficacy, safety data, and pharmacoeconomic considerations regarding cost-effectiveness and budget impact of the assessed therapy.26 Reimbursement rate is defined on the basis of pre-defined legislative criteria. It could be partial (up to 50% or 75%) or full (100%) as the reimbursement rate for inpatient treatment of obligatory health insured patients with psychotropic medicines is 100% and for outpatient – 50% or 100%.27

While the psychiatric inpatient care in Bulgaria is financed by the government regardless of patients’ health insurance status, outpatient psychiatric care is funded by the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF). Only citizens with health insurance are privileged to take reimbursed medications, therefore the increased rates of unemployment and poor socio-economic status of the families of the severely mentally ill pose a high risk for the patients to remain without the health insurance and thus unable to take reimbursed medications.28,29 Another bureaucratic complication is that the diagnostic category schizoaffective disorders (F25 according to ICD-10) in Bulgaria is not included in the Positive Drug List, and therefore psychotropic medication prescribed for this diagnosis cannot be reimbursed by the NHIF. This could also be the reason for the overrepresentation of the diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia, as seen in our results.

The prevalence of mental disorders and hospitalized morbidity in Bulgaria remains without significant change in the examined period.30 Therefore the possible reasons to explain the decrease in the number of reimbursed patients might be low adherence rates to outpatient treatment,31 possibly difficult access to mental health care10 or significant stigma of mental illness17 that could be preventing the use of reimbursed medicines in outpatient settings. Another possible explanation might be a decrease in the cost of psychopharmacotherapy related to the entrance of generics with a lower price that might make psychotropic medications more affordable to buy out-of-pocket. The influence of generics might be a possible reason for the reduction of the costs as it was demonstrated for cardiovascular medicines by Mitkova et al.32

Although new modern medicines have been introduced for the therapy of psychiatric disorders and most of them are included in the treatment practice of Bulgarian patients, still, prescribers rely on well-established molecules.33,34 Similar to other studies, we report a stable use of anxiolytics, while sedatives and typical antipsychotics decrease by 26.4% and 61.2%, respectively.13 The utilization of all ATC groups is decreasing from 28.04 to 17.38 DDD/1000inh/day for 5-year period in Bulgaria, which is similar with the observed trend for the overall utilization of antipsychotics in Serbia and Montenegro: from 45.1 DDD/1000 inhabitants/day in 2000 to 69.1 DDD/1000 inhabitants/day in 2004.13 It is worth mentioning that Lithium, a well-established drug for the treatment of bipolar disorder, is not included in the Positive Drug List and is not available for use in Bulgaria.35

The main limitation of the study that it is only summarizing the publicly available macro indicators for the utilization of psychotropic drugs for major psychiatric disorders at a reimbursed level. Also, thymostabilizing agents such as carbamazepine and valproic acid are not included in the analysis due to the lack of disaggregated data by diagnosis from the NHIF database. However, the study can elucidate the lack of sufficient publicly available data on the real dispensing strategies in the country, regardless of health insurance status. Lack of such data is detrimental to the development of effective strategies for mental health care. The hypotheses about the possible reasons for these results require further investigation and could be used as a base for further analysis.

As Soumerai et al. reported, the limits on coverage for the costs of prescription drugs can increase the use of acute mental health services among low-income patients with chronic mental illnesses and increase the treatment costs paid by public funds.36 Therefore, further more detailed studies focusing on analysis of the Bulgarian patients’ access to reimbursable psychotropic medicines and the related factors are required.

ConclusionThe number of reimbursed patients with major psychiatric disorders in Bulgaria, as well as the cost of pharmacotherapy and utilization of psychotropic medicines, decreases during 2013–2017. Further analysis of the possible reasons is required to facilitate better and effective mental health care strategies.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest.

FundingThis work was supported by the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science under the National Program for Research ‘Young Scientists and Postdoctoral Students’.

Ethical considerationsThe work does not involve any human beings or animals.