Most scientific literature assumes that entrepreneurial activity, in a broad sense, is positive for economic growth. Our work analyses 74 economies in a period of 6 years, identifying those factors related simultaneously with an entrepreneurial spirit and economic growth. The results enable to know the impact of a specific factor on entrepreneurship and economic growth. Additionally, we suggest that entrepreneurial activity plays a different role depending on the economic stage of the country in question. On the other hand, less developed countries should not be based on generic entrepreneurship if the objective they pursue is to promote economic growth.

There is a certain scientific consensus that the entrepreneurial activity, in some of its manifestations, is related to economic growth (Almodovar-Gonzalez, Sanchez-Escobedo, & Fernandez-Portillo, 2019; García-Rodríguez, Gil-Soto, Ruiz-Rosa, & Gutiérrez-Taño, 2017; Gómez-Gras, Mira-Solves, & Martínez-Mateo, 2011; Hormiga, Batista-Canino, & Sánchez-Medina, 2011). But this relationship, far from being clear (Carree & Thurik, 2008), has not achieved satisfactory models (Liñán & Fernández-Serrano, 2014), and poses several challenges to the academic world.

Perhaps, the most unknown thing about this relationship is projected on the causality between the variables involved, since "the causality between entrepreneurship and economic growth has not been established conclusively" (Valliere & Peterson, 2009:460).

To this, we must add that, in addition to economic growth and entrepreneurial activity, some many factors or variables come into play (Carree, Van Stel, Thurik, & Wennekers, 2007), and that these factors are established by researchers based on the macroeconomic theory.

In this sense, our research aims to establish an empirical model that allows for the interpretation of results from the different theories of economic growth, and from different approaches to the causality between economic growth and entrepreneurial spirit, without making any assumption about the direction between the variables.

We also want to point out that this work is based on the concept of generic entrepreneurship understood as "Any action intended to start a business, regardless of its features, not related to any specific type of entrepreneurship" (Almodóvar, 2018:226)

To do so, before defining our objectives, we synthesized two groups of main problems. The first problem is the assumption of the productivity of the entrepreneurial activity, which includes two aspects: the acceptance that generic entrepreneurship always has positive effects (Fadahunsi & Rosa, 2002; Audretsch, 2009), and the position of certain academics who deny this statement (Liñán & Fernández-Serrano, 2014; Schott & Jensen, 2008; Valliere & Peterson, 2009; Wong, Ho, & Autio, 2005). In many cases, researchers assume the positive effects of entrepreneurship, without taking into account the existence of destructive entrepreneurship (Desai, Acs, & Weitzel, 2013).

The second problem is Entrepreneurial activity based on the stage of economic development of the countries, which refers to the existing dichotomy between those researchers who defend the creation of companies to achieve economic objectives in developing countries, and those who oppose that position. These approaches suggests that for developed countries, entrepreneurship has a positive impact, which is measured by economic growth (Audretsch, 2012), and in countries with negative development (Acs & Varga, 2005; Sautet, 2013; Van Stel, Carree, & Thurik, 2005; Wennekers, Van Stel, Thurik, & Reynolds, 2005).

Given these scientific debates, we have the following research questions: (a) Is generic entrepreneurial activity related to economic growth?, and, (b) from economic growth, should the generic entrepreneurial activity be encouraged in developing countries, bearing in mind that some authors point to a different impact depending on the type of economy, in particular, a negative impact in developing countries?

Therefore, based on the problems defined and on the research questions posed, two objectives are established: Objective 1: To study the possible existence of factors related to generic entrepreneurial activity and economic growth. Objective 2: To study the possible difference in the economic impact of entrepreneurial activity between economies, especially the possible existence of factors positively related to generic entrepreneurial activity and economic growth.

As key contributions of our research we can highlight the convenience of encouraging generic entrepreneurship in advanced economies, and the inconvenience of increasing generic entrepreneurial activity in the most disadvantaged economies are confirmed. Also, there are signs of a possible endogeneity of the entrepreneurial spirit to economic growth in developing countries.

Furthermore, two new approaches are used: First, the classification of the economic stage of each country is made based on the entrepreneurial impact instead of on the income level. And second, the statistical model is not restrictive regarding the causality of the variables, that is, it can be interpreted that entrepreneurship depends on economic growth and vice versa.

After this introduction, a theoretical framework of analysis is established, the methodology used is defined, the results are presented and a discussion and conclusions have presented that cover the limitations and future lines of research.

2Entrepreneurial activity and economic growth2.1Relationship between entrepreneurial activity and economic growthA common error in the study of entrepreneurship is the acceptance that its effects in economic terms are always positive. In many cases, researchers assume the positive effects without taking into account that these activities can also be destructive (Desai et al., 2013).

In this sense, Audretsch (2009) emphasises how public powers encouraging entrepreneurship without solid evidence to justify it. In this desire, they are only concerned with promoting entrepreneurship, without taking into account the type of activity, which can lead to unexpected results (Fadahunsi & Rosa, 2002).

Generic entrepreneurship is not the same as the specific types of entrepreneurial activity. Following this investigation, studies such as those by Liñán and Fernández-Serrano (2014), show a negative relationship when comparing generic entrepreneurship (measured by the TEA variable of the GEM project) with economic growth, and yet specific business initiatives (based on opportunity) can be associated with higher income levels. Wong et al. (2005) find evidence of the existence of activities that do not contribute to the economy, where only new high potential companies show a significant impact on economic growth. In the same vein, Valliere and Peterson (2009) attribute an impact on economic growth (in developed countries) only to high expectation entrepreneurs.

As research suggests, new activities based on necessity are located more intensely in the weakest economies, while in developed economies there are more initiatives based on opportunity. The literature indicates a relationship between the type of economy and the type of business that is created: opportunity-driven entrepreneurs prevail in high-income countries, while those based on necessity predominate in low-income countries (Amorós, Fernández, & Tapia, 2012). As indicated by Larroulet and Couyoumdjian (2009), advanced economies have low total entrepreneurship rates, but a higher rate of entrepreneurship based on opportunity compared to necessity. On the contrary, less developed countries have higher rates of total entrepreneurial activity, although the relative presence of entrepreneurship based on opportunity is lower. Acs and Varga (2005), find that opportunity has a significant positive effect on economic development, while new activities based on necessity do not affect. Aparicio, Urbano, and Audretsch (2016) find a positive relationship between new business based on opportunity and economic growth, indicating that activities based on necessity have no long-term effect on economic growth. In short, progress towards development represents moving away from entrepreneurship based on necessity (Sautet, 2013).

Why are the type of entrepreneurial activity and economic growth related? Research suggests that the answer lies in the quality of entrepreneurship. Anokhin and Wincent (2012) point out that opportunities differ between developing and developed countries, and for the latter, the initiatives are of higher quality (Shane, 2009). The point of greatest consensus is about the lack of impact of entrepreneurship based on necessity (Valliere & Peterson, 2009) and that it does not manage to boost economic growth (Sautet, 2013).

On another front, differentiating between the exogenous variable in the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth is a challenge which scientific research continues to face. This is why Valliere and Peterson (2009: 460) maintain that "the causality between entrepreneurship and economic growth has not been conclusively established". Given this ambiguity, opposing positions arise.

Authors such as Acs, Audretsch, Braunerhjelm, and Carlsson (2012: 297) state that "the results have proven to be remarkably robust concerning the impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth". On the other hand, researchers such as Fritsch and Schroeter (2011) propose that the level of economic development leads to the creation of companies, which is justified because the opportunities and the expected rewards are greater. In the work by Koellinger and Thurik (2012) it is shown that entrepreneurship can be a consequence of economic growth.

Finally, the idea of a double causality is also expressed. Amorós et al. (2012) point out a reciprocal relationship, where the state of development stimulates new economic activities and the creation of companies contributes to development. Besides, Aparicio et al. (2016) state that there is a feedback effect between them. In short, these contradictions reinforce the words of Carree and Thurik (2008), who state that the relationship is unclear.

In practice, different examples that assume the causality in both directions can be found, some of which are listed in Table 1.

Different directions of the causality of the entrepreneurial activity-economic growth relationship.

| Authors | Independent variable | Dependent variable |

|---|---|---|

| Van Stel et al. (2005) | Entrepreneurship | Economic growth |

| Wong et al. (2005) | Entrepreneurship | Economic growth |

| Wennekers et al. (2005): Creating U curve | Economic growth | Entrepreneurship |

| Carree et al. (2007): Several models | Economic growth | Entrepreneurship |

| Wennekers et al. (2007) | Economic growth | Entrepreneurship |

| Carree and Thurik (2008) | Entrepreneurship | Economic growth |

| Valliere and Peterson (2009) | Entrepreneurship | Economic growth |

| Pinillos and Reyes (2011) | Economic growth | Entrepreneurship |

| Acs et al. (2012) | Entrepreneurship | Economic growth |

| Van Praag and Van Stel (2013) | Entrepreneurship | Economic growth |

| Liñán, Fernández-Serrano, and Romero (2013) | Economic growth | Entrepreneurship |

| Liñán and Fernández-Serrano (2014) | Entrepreneurship | Economic growth |

| Galindo and Méndez (2014): Double causality | Econ.growth/Entrepreneurship | Econ. growth/Entrepreneurship |

| Dau and Cuervo-Cazurra (2014) | Economic growth | Entrepreneurship |

| Urbano and Aparicio (2016) | Entrepreneurship | Economic growth |

The difference in the impact of entrepreneurship depending on the economic stage is statistically based on the direct U adjustment. (Wennekers et al., 2005). Its application to the entrepreneurship-economic growth relationship will support that the first part of the function will show an inverse relationship between new economic activities and economic growth, and a second part with a direct relationship.

The empirical evidence shows the dynamics of entrepreneurship differs among the stages of development (Amorós et al., 2012; Urbano & Aparicio, 2016). U curve implies a negative (or null) impact of entrepreneurship on less developed economies and positive on developed ones (Van Stel et al., 2005; Wennekers et al., 2005). Also, it reflects how entrepreneurship is greater in developing countries compared to developed ones (Acs & Amorós, 2008; Carree et al., 2007; Van Stel et al., 2005).

Academics provides several explanations for this. For example, Díaz, Almodóvar, Sánchez, Coduras, and Hernández (2013) explain the "U" function under the prism of institutional quality and the stages of Porter, Sachs, and McArthur (2002). In factor-driven, a negative relationship between entrepreneurship and institutional quality is produced. In the efficiency-driven stage, activities motivated by necessity are abandoned. Finally, in the innovation-driven stage, where a legal framework has been consolidated, together with new business opportunities, an increase in the creation of companies is produced.

Other authors use types of entrepreneurial activity (opportunity-necessity). For example, Liñán and Fernández-Serrano (2014) argue that wealthy countries offer more opportunities. Sautet (2013) also explains the U curve going from necessity (developing countries) to opportunity (typical of developed countries).

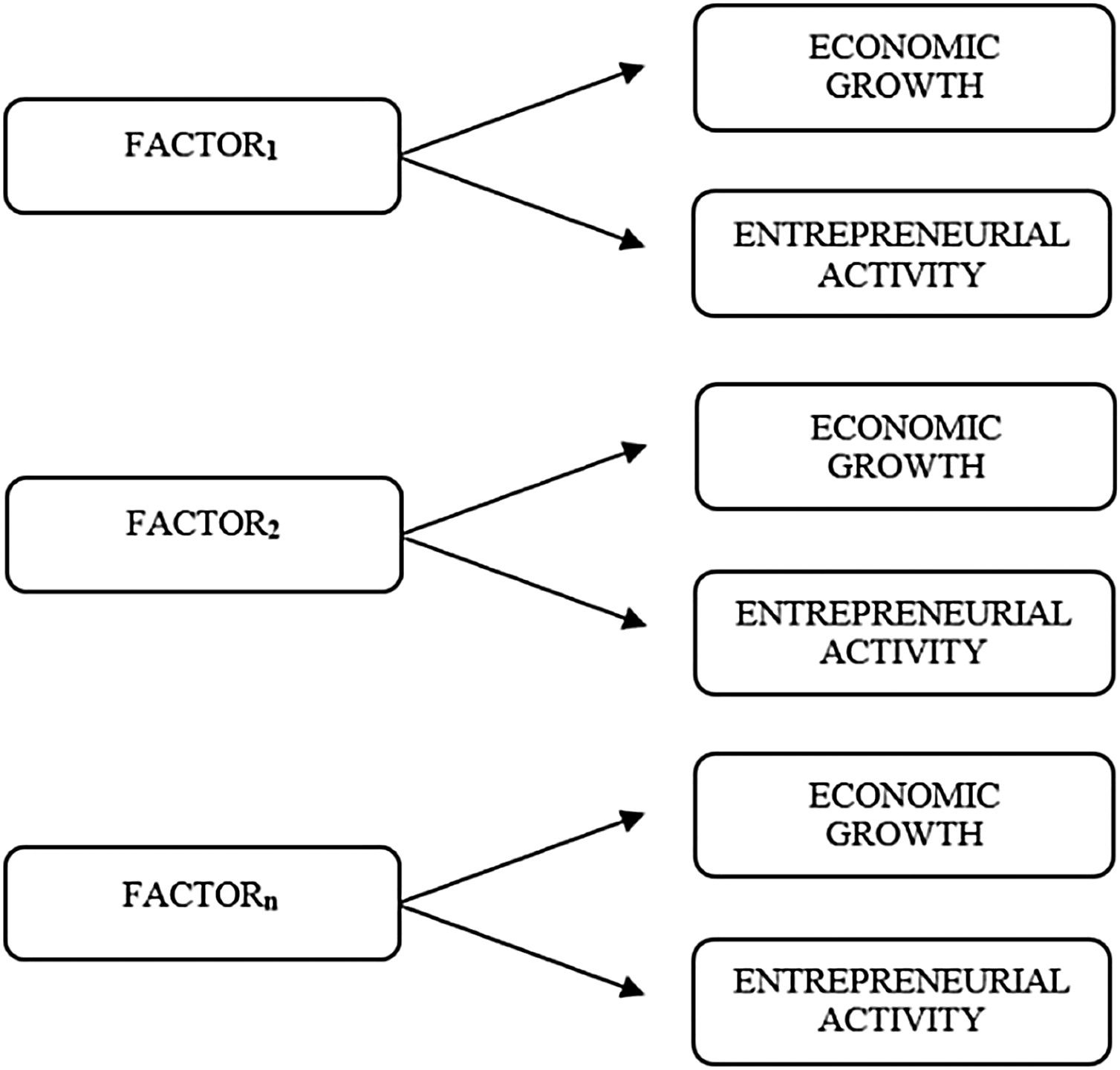

3Conceptual model and hypotheses3.1ApproachWe aim to approach the problem of the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth without directly confronting the direction of causality. Thus, the approach seeks the connection at the origin and focuses on the factors that jointly determine both entrepreneurial activity and economic growth, so if the same factor boosted entrepreneurship and economic growth, both would be related (see Fig. 1). The key would be to find factors that have a common influence between the two variables mentioned, that is, that they serve as a link under their reciprocal influence, both on entrepreneurship and economic growth.

Based on this approach, the two proposed objectives were established. In the first place, and without assuming their existence, the possibility of there being factors that are related (positively or negatively) simultaneously to the two variables is explored. If objective one is fulfilled, we move on to the next one, specifically, to study the possibility of a differentiated impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth depending on the stage of economic development of the country (see Fig. 2), with emphasis on the exploration of some factor that can promote entrepreneurship in a productive way.

3.2HypothesesAs stated, the assumptions of the approach are conditional and need to be refuted, and therefore, our hypotheses study the possible existence of these factors reciprocally related to economic growth and entrepreneurial activity.

Therefore, having raised the first research problem, we question whether the generic entrepreneurial activity is related to economic growth (Gómez-Gras et al., 2011; Hormiga et al., 2011; Wennekers et al., 2005) through the first hypothesis: H1: There are factors with a reciprocal relationship between entrepreneurial activity (generic) and economic growth.

To study objective 2, we state 2 hypotheses, which represent the two sides of the same coin, so that they are stated in the following way: H2a: In developing countries, factors related to entrepreneurial (generic) activity have a negative impact on economic growth.

As indicated by part of the literature, entrepreneurship has a negative impact on economic growth in developing countries (Acs & Varga, 2005; Sautet, 2013; Van Stel et al., 2005; Wennekers et al., 2005), so it can be assumed that those factors (independent variables) that encourage entrepreneurship will hinder economic growth, and those factors that have a negative impact on the number of activities, will improve economic growth. Note that if hypothesis 2a is not fulfilled, it is because some factor (independent variable) with the capacity to promote the creation of companies in a productive way (in terms of economic growth) has been identified, in other words, if the hypothesis is fulfilled it is because all the possible factors that support the emergence of new businesses will generate an economic decline (and vice versa). H2b: In developed countries, the factors related to entrepreneurial activity (generic) impact in the same direction on economic growth.

If entrepreneurship has a positive impact in developed countries (Wennekers et al., 2005; Acs & Varga, 2005; Audretsch, 2012), it can be assumed that those factors (independent variables) that promote entrepreneurship also promote economic growth, and those factors that have a negative impact on entrepreneurship, will also have it on economic growth.

4Methodology4.1Source of data and variablesWe use two dependent variables. Fist, entrepreneurial activity, measured by the Total Early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) from GEM, which is an aggregate variable at national level that reflects the percentage of the population between 18–64 years that claims to be involved in an entrepreneurial initiative of any kind, which does not exceed 42 months of activity. Second, economic growth, measured by Gross Domestic Product per capita in purchasing power parity in US dollars at current prices in dollars (GDP ppp current $). It was obtained from the World Development Indicators (WDI). It is defined as the GDP in terms of population, calculated without taking into account depreciation and denominated in current US dollars.

The independent variables were obtained from the World Bank database (WDI), which is available for 153 countries and consists of 1195 variables. The variables are divided into 10 large areas, which are listed in Table 2, together with their description and the number of initial variables that the database contains and those that were finally left for our investigation once a series of criteria that eliminated redundant variables were applied or that were outside the scope of this investigation. Altogether there were 524 left.

10 areas of WDI, number of variables and number of simplified variables.

| Education | Environment. | Economic Policy and debt | Financial sector | Health | Infrastructure | Work and social protection | Poverty | Private sector and trade | Public sector | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 89 | 140 | 432 | 49 | 94 | 55 | 93 | 18 | 147 | 78 | 1195 |

| Final | 31 | 59 | 93 | 45 | 41 | 37 | 29 | 13 | 127 | 49 | 524 |

The sample includes all countries with available data (74 economies) for the variables of a period of 6 years. Each statistical case refers to a country in a specific year. A total of 248 cases are formed, representing all the countries that have participated in the GEM project from 2004 to 2009, except Puerto Rico in 2007 and the Palestinian Territories in 2009 (no data for GDP).

Once the sample size was indicated, the sample universe in 1128 cases, (188 countries adhered to the World Bank for 6 years) was estimated. We classify the countries into 2 groups according to the relationship shown between GDP and TEA. If it is inverse (the higher the GDP the lower the TEA) they are included in group 1 (C1 according to our notation), if it is direc,t they are included in group 2 (C2). Thus, we interpret the concept of a developed economy as that characterized by a productive entrepreneurial activity (in terms of economic growth) and developing economies by unproductive entrepreneurship.

We start with the GDP/TEA curve, and annually, we discriminate depending on the position they occupy concerning the inflexion point. The cases located to the left of the minimum show an inverse relationship and are part of C1, the cases to the right, with a direct GDP/ TEA ratio, are included in C2.

In Figs. 3 and 4, we can see how the classification would be in two groups for a given year. At a conceptual level, the fact of having divided it into two groups allows us to interpret the cubic model in two lines (Fig. 4): one with an inverse relationship (C1) and the other one with a direct relationship (C2).

Once the economies are classified with these parameters (Table 3), we can divide the 248 statistical cases into a developing and developed economies. Note that each statistical case represents a country for a year, so their classification can vary from one year to the next. If we contrast the resulting classification with the classification of the Global Competitiveness Report, we observe a coincidence of more than 99%.

Cubic regression GDP/TEA and annual minimum*.

| Year | Regression | Parameters | Minimum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | F | gl1 | gl2 | Sig. | b0 | b1 | b2 | b3 | ||

| 2004 | 0.625 | 16.69 | 3 | 30 | 0.000 | 3.81E+01 | −3.69E-03 | 1.30E-07 | −1.40E-12 | 22356.10 |

| 2005 | 0.347 | 5.50 | 3 | 31 | 0.004 | 2.51E+01 | −1.89E-03 | 5.71E-08 | −5.08E-13 | 24709.71 |

| 2006 | 0.466 | 11.04 | 3 | 38 | 0.000 | 2.59E+01 | −1.79E-03 | 4.89E-08 | −4.07E-13 | 28140.13 |

| 2007 | 0.441 | 9.74 | 3 | 37 | 0.000 | 2.50E+01 | −1.47E-03 | 3.49E-08 | −2.48E-13 | 31990.28 |

| 2008 | 0.525 | 14.38 | 3 | 39 | 0.000 | 2.69E+01 | −1.67E-03 | 4.15E-08 | −3.10E-13 | 30613.75 |

| 2009 | 0.577 | 22.25 | 3 | 49 | 0.000 | 2.65E+01 | −1.72E-03 | 4.29E-08 | −3.11E-13 | 29491.27 |

*Each year the cubic curve is calculated, as well as the annual minimum.

*We calculate the regression between TEA and GDP, where the coefficients b represent the estimated parameters. The annual minimum is obtained by making the first derivative equal to zero and verifying that the value of the second one is greater than zero.

The empirical study is based on the pooled analysis with Ordinary Least Squares, which will be used to estimate the seven years together. Even though this analysis has a limitation, a statistic that specifies the possibility of bias due to unobservable heterogeneity, there are examples of its application in the literature (Wennekers, Thurik, Van Stel, & Noorderhaven, 2007 or Díaz et al., 2013). In addition to the criteria, stricter than usual, established by Díaz et al. (2013), we added some additional criteria, thus being more demanding regarding the firmness and representativeness of the regressions from year to year. The five established criteria are summarized in Table 4.

Summary of criteria.

| GDP | TEA | |

|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | R-pooled>0.2 (α=0.01)n-pooled of R: n>75% total casesSign R2-pooled= Sign of R2i,, …, R2j; i=2004 j=2009R2i>0,, …, R2j>0; i=2004 j=2009R2-adjusted pooled>0,15 (α=0.01) | R-pooled>0.2 (α=0.01)n-pooled of R: n>75% total casesSign R2-pooled= Sign of R2i,, …, R2j; i=2004 j=2009R2i>0,, …, R2j>0; i=2004 j=2009R2-adjusted pooled>0,15 (α=0.01) |

This work carries out 2096 regressions, because 524 dependent variables are used, which were regressed once for the TEA, and another time for the GDP. This process is done twice, once for developing country economies, and once for developed countries.

5ResultsOf the 524 independent variables considered (factors), we find several that have exceeded the statistical model, in particular, 44 variables, which will be considered as factors with simultaneous influence on economic growth and entrepreneurship. Of these factors, 37 appear in developing countries and 7 in developed countries (see Fig. 5).

Based on these data, it should be pointed out that regarding the first objective, the existence of factors with a reciprocal relationship between the entrepreneurial activity and economic growth is confirmed, so we accept hypothesis 1.

The second objective has been confirmed, as we observe a different functioning, analysed through factors, of the entrepreneurship-growth relationship depending on the economic stage.

In short, we have found a relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth through factors, but these behave differently depending on the economy in which they are applied. Besides, and because of the performance observed in developing countries, we have not been able to identify the existence of factors positively related to generic entrepreneurship and economic growth, which, according to our research, we did not find variables with which to promote entrepreneurship productively in these economies.

The results summarized in Table 5, indicate that none of the variables of the model in group 1 maintains a relationship in the same direction with the GDP and the TEA, that is, if the relationship of a variable is inverse with the GDP, it will be direct with the TEA (and vice versa). Thus, we are in a position to accept that in developing countries the factors related to entrepreneurial activity impact on economic growth in a different direction (Hypothesis 2a).

Summary of results in developing countries.

| Area | Independent variable | Dependent | Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Student-teacher ratio, primary level | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Direct |

| School enrolment, secondary level (gross %) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| School enrolment, tertiary level (gross %) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Environment | Electricity consumption (Kw/h per capita) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse |

| Energy use (kg of equivalent oil per capita) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Growth of the urban population (annual %) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Direct | |

| Economic policy and debt | Final consumption expenditure of the general government | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse |

| Services, etc., added value (% of GDP) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Infrastructure | Subscribers to fixed broadband (per 100 people) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse |

| Internet users (per 100 people) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Subscriptions of cell phones (per 100 people) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Motor vehicles (per 1000 inhabitants) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Private vehicles (per 1000 inhabitants) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Road sector (roads) diesel fuel consumption per capita (kg oil equival.) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Telephone lines (per 100 inhabitants) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Health | Fertility rate in adolescents (birth per 1,000 women aged 15 and 19) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Direct |

| Inactivity rate by ages, people aged 65 and over (% of working-age) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Inactivity rate by ages, people under 15 (% of working-age population) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Direct | |

| Birth rate, live births in one year (per 1,000 people) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Direct | |

| Fertility rate, total (birth number per woman) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Direct | |

| Health expenditure per capita, PPA (2005 constant international US$) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Health expenditure, public sector (% of GDP) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Population aged between 0 and 14 (% of total) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Direct | |

| Population aged 65 and over (% of total) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Population growth (annual %) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Direct | |

| Work and social protection | Jobs in industry (% of total jobs) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse |

| Vulnerable employment, total (% of total employment) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Direct | |

| Wage earners, total (% of total hired) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Private sector and trade | Consolidated rate, simple average, all the products (%) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Direct |

| Consolidated rated, simple average, manufactured products (%) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Direct | |

| Consolidated rated, simple average, primary products (%) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Direct | |

| Merchandise exported to developing economies in Europe and Central Asia (% of total merchandise exported) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Share of tariff lines with specific rates, all the products (%) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Share of tariff lines with specific rates, primary products (%) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Public sector | Customs and other taxes on imports (% of tax revenue) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Direct |

| Expenditure (% of GDP) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse | |

| Collection, excluding donations (% of GDP) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Inverse |

In the same way, and based on the results summarised in Table 6, we observe that none of the variables of the model in group 2 maintains a relationship in a different direction with GDP and TEA, that is, if the relationship of a variable is inverse with the GDP, it is also reverse with the TEA and vice versa.

Summary of results of developed countries.

| Area | Independent variable | Dependent | Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Public expenditure on education, total (% of government expenditure) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Direct |

| Health | Inactivity rate by ages, people aged 60 and over (% of working-age) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Inverse |

| Population aged 60 and over (% of total) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Inverse | |

| Work and social protection | Relationship between employment and population, aged over 15, tot.(%) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Direct |

| Active population rate, total (% of total population aged over 15) | GDP/TEA | Direct/Direct | |

| Long-term unemployment (% of total unemployment) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Inverse | |

| Private sector and trade | Procedures to register a property (number) | GDP/TEA | Inverse/Inverse |

| Links | |

|---|---|

| Research card | |

| Universe | Possible cases: 1128. Calculated from the 188 countries adhered to the World Bank, during a period equivalent to that of our study (6 years) |

| Geographical area | 74 countries |

| Geographical level | Spatial delimitation is done at country level |

| Time range | 6 years. Period: 2004-2009 |

| Sample unit | Each statistical case is formed with a country (Ci) in a year (Cn). Ci, Yn i=1,…, 75 n=2004,…,2009. |

| Sample design | All data available of the participating countries in GEM 2004-2009Exceptions due to lack of data in the independent variables:

|

| Sample size | 248 cases. Formed by the binomial country/year |

| Sample distribution | 139 cases for developing economies109 cases for advanced economies |

| Sample error | 5,5% for a confidence level of 95% and a heterogeneity of 50% |

| Collection method | Secondary data (from GEM and IDM) |

| Data access | August 2011 |

| Estimation model | OLS pooled regression. Increased criteria of Díaz et al. (2013) |

| Dependent variables | Entrepreneurship: TEA of the GEM project |

| Economic growth: GDP pc PPP (IDM) World Bank | |

| Independent variables | 524 variables. 10 areas (HDI) of the World Bank |

| Analysis software | IBM SPSS Statistics 21 and Derive 5.0 |

Therefore, we accept that in developed countries the factors related to the entrepreneurial activity impact on economic growth in the same direction (hypothesis 2b).

Finally, and once the acceptances of hypotheses H2a and H2b have been discussed, it can be said that objective 2 has been partially achieved, in the sense that we can study the possible difference in the economic impact of entrepreneurial activity between economies (first part of objective 2), but we have not been able to identify the second part of the objective that referred especially to the possible existence of factors positively related to generic entrepreneurial activity and economic growth.

6Discussion and conclusionsOur results indicate, on the one hand, the existence of a relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth, and on the other hand, differentiated behaviour between developed economies and developing economies.

The fact that in the environment of advanced countries, what drives entrepreneurship is also economically beneficial, and that in the context of the poorest countries, if a factor intensifies entrepreneurial activity, it slows down economic growth, in principle it shows that promoting entrepreneurship is not relevant for developing countries, though for developed countries it is.

The proposal that entrepreneurial activity is positive in developed countries and negative in developing countries should always be interpreted with the adjective generic. Thus, our work does not contradict those who defend entrepreneurship based on an opportunity in less advanced countries (Amorós et al., 2012; Aparicio et al., 2016), since this entrepreneurial initiative is a specific category, so it is not generic.

It is true, and it may be an explanation for our results, that generic entrepreneurial activity has a stronger necessity component in developing countries, and of opportunity in developed countries (Amorós et al., 2012; Larroulet & Couyoumdjian, 2009; Valliere & Peterson, 2009), having the former negative consequences (Sautet, 2013) and the latter positive consequences (Aparicio et al., 2016).

The results in developing countries seem to be describing the environmental factors of the GEM growth model (Kelley, Bosma, & Amorós, 2011). On the other hand, the explanation of the influence of these factors in developing countries is easily explained from economic growth, but difficult to explain from the entrepreneurial activity one. We want to express that our results raise the possibility of a relationship of dependence of entrepreneurship on economic growth in developing countries, which could be explained by the levels of necessity for entrepreneurial activity. These levels are higher in developing countries formed by basic subsistence companies (Valliere & Peterson, 2009), and show zero economic growth (Acs, Desai, & Hessels, 2008; Aparicio et al., 2016). It is no coincidence that the decreasing part of "U" can be explained by a high prevalence of necessity entrepreneurs in the most disadvantaged economies (Valliere & Peterson, 2009). We add a passive character of entrepreneurship based on the necessity to these statements since it is not a decision that is made between two alternatives but represents the only possible option in the absence of work. In other words, it is a business initiative motivated by the economic situation, and that is why we suggest the possibility of entrepreneurship in the face of economic growth in developing countries.

In developed countries there is a debate about whether to consider growth as exogenous (Dau & Cuervo-Cazurra, 2014; Wennekers et al., 2007), or to consider entrepreneurship exogenous (Carree & Thurik, 2008; Liñán & Fernández-Serrano, 2014), and even the possibility of double causality (Aparicio et al., 2016; Galindo & Méndez, 2014).

In any case, our study suggests that boosting new businesses is not always appropriate in less developed countries if the objective is to favour economic growth. In this line, we find support in those authors who discourage promoting entrepreneurial activity in less favoured economies (Anokhin & Wincent, 2012; Valliere & Peterson, 2009) and propose to focus on the exploitation of economies of scale, the attraction of foreign investment, or the development of human capital. By contrast, for developed countries, generic entrepreneurial activity is related to economic growth, and its promotion is useful to increase the wealth of a country.

As indicated, in this sense there are opposing positions that suggest the possibility that under certain circumstances, even in development contexts, generic entrepreneurship may not be as good as some public authorities have assumed (Audrestsch, 2009).

The prime implication that emerges from our work consists of the usefulness of measuring the impact of new businesses, based on the fact that the impact in terms of national wealth is not always positive. On the other hand, and contrary to what could be interpreted by our conclusions, academics should not rule out promoting new activities as a means to achieve economic growth in poorer countries, where certain specific forms of qualitative nature must be promoted, give rise to a smaller number of businesses, but of higher quality.

We specifically identify the following limitations: (a) the use of a statistical model based on pooled regressions has unobservable heterogeneity problems. However, when using the pooled model used by Díaz et al. (2013), which mitigated this problem, and adding some additional criteria to this model; (b) there is a problem derived from the use of the "U" model, which is the interpretation of results in economies that are close to the turning point of the curve, so for these types of countries, our recommendations should be taken with caution; and (c) this work does not analyse time delays.