The term dysphagia lusoria refers to symptoms that arise from vascular compression of the oesophagus.1 This clinical entity was first reported by Bayford in 1787 in a woman with a long history of dysphagia, in whom an aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA) was found during autopsy.2 This artery abnormality was known as luxus nature before the term dysphagia lusoria was adopted. The prevalence of ARSA in the general population is estimated to be between 0.4% and 0.7%. Dysphagia lusoria is caused by the abnormal regression or failure to develop of the right fourth aortic arch during embryonic development.3 In these cases, the right subclavian artery of the aortic arch runs towards the right arm behind the oesophagus and trachea in 80% of cases, between the trachea and the oesophagus in 15% of cases and in front of both in 5%.4

It may be asymptomatic in childhood or manifest with respiratory symptoms during ingestion owing to tracheal compression, as its elasticity is greater in infancy. Symptom onset is rare in adults and tends to manifest in the form of dysphagia arising from greater oesophageal rigidity and arteriosclerosis. Treatment will depend on symptoms, age, associated comorbidity as well as other concomitant vascular anomalies.5

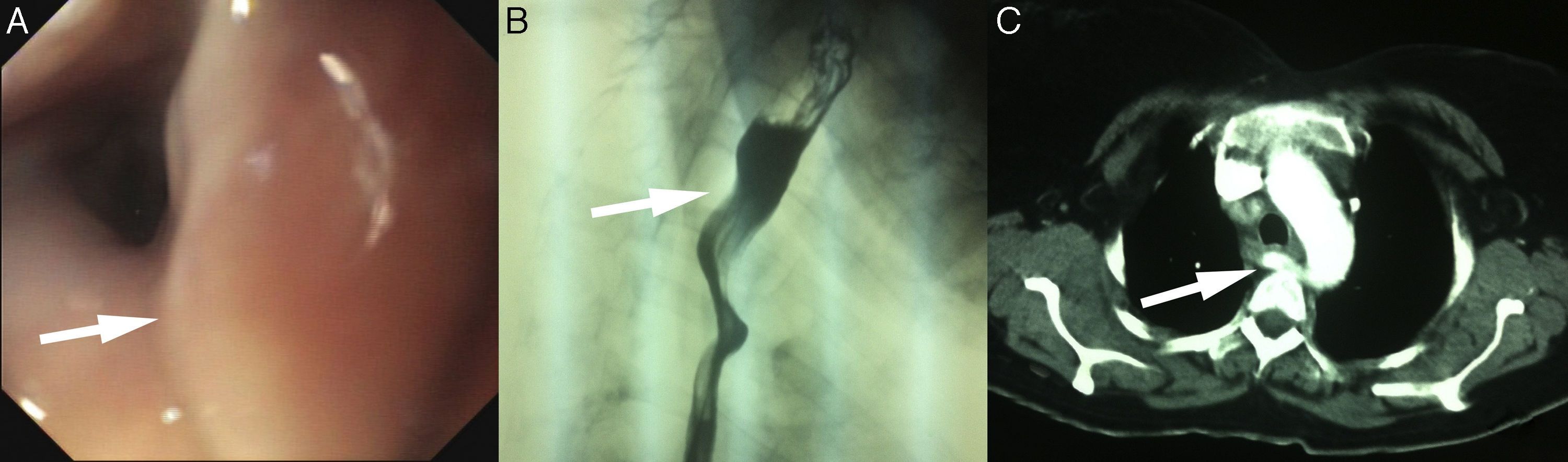

We present the case of a 45-year-old woman who attended our practice with a four-year history of intermittent dysphagia for both liquids and solids, together with occasional vomiting. The patient was in psychiatric follow-up for a behaviour disorder and was being seen by an endocrinologist for multinodular goitre, with no other medical history of interest. The patient reported that the dysphagia had intensified in the last few months, accompanied by weight loss of 68kg in the last three months. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGE) was performed, which revealed a throbbing area that slightly occluded the lumen of the upper third of the oesophagus. The study was completed with an upper gastrointestinal series (UGI) and computed tomography (CT) scan. The UGI revealed an oesophageal impression suggestive of extrinsic compression in the upper third of the oesophagus. ARSA was confirmed in the CT scan (Fig. 1). Changes to diet and swallowing were sufficient to improve the patient's symptoms, and the patient is currently asymptomatic after four years of follow-up.

(A) Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. The arrow indicates a throbbing area suggestive of a vascular anomaly. (B) UGI. The arrow indicates the oesophageal impression secondary to an aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA). (C) Computed tomography. The arrow indicates the ARSA and how it displaces the oesophagus to the left.

Although symptoms rarely manifest in the reported cases of ARSA, prevalence ranges from 7 to 40% depending on the author.3,6 Patients with dysphagia lusoria usually present latent symptoms that hinder its diagnosis. It is extremely common practice to conduct multiple examinations as an aberrant artery is not usually suspected as the cause of dysphagia. In this case, the examinations were performed years after the onset of symptoms, given both the patient's relatively mild intermittent dysphagia and her psychiatric medical history. The patient underwent an annual neck ultrasound to monitor her goitre and this was ruled out as being the cause of the dysphagia owing to its small size. Other symptoms associated with dysphagia may manifest, such as weight loss (as in our case), chest pain, occasional vomiting, etc., which may lead us to suspect an organic disease.4 Given its general frequency, it is also important not to assume that the psychiatric disorder is the cause of the dysphagia.

The UGE, which must be performed to rule out other causes of dysphagia, may fail to diagnose the condition (in up to 20% of cases).1 In this case, a throbbing area suggestive of a vascular anomaly was identified, which was subsequently confirmed with the UGI and CT scan. The angiography identified this aberrant artery and enabled the vascular map of the area to be more clearly seen. Given that angiography is an invasive procedure, we believe that it should only be used if the vascular anomaly is to be surgically corrected. In this case, the CT scan, which has demonstrated a sensitivity of 100% in some cases, confirmed the presence of the aberrant artery.7 The initial treatment of dysphagia lusoria largely depends on the severity of symptoms. In mild-moderate cases, as with our patient, initial treatment should comprise changes to the diet, with an increased consumption of soft foods and smaller portion sizes, coupled with improved swallowing technique by eating more slowly and chewing more thoroughly.3 Some studies have shown dysphagia improvement by also adding proton-pump inhibitors and/or prokinetics.8 Surgery may be necessary if symptoms do not improve despite dietary changes, or in the event of an aneurysmal dilatation close to the route of the artery.9,10 Age is also an influential factor, as surgery is the treatment of choice in children with respiratory symptoms or oesophageal compression to prevent symptoms from deteriorating.5 Conservative treatment (changing the diet and swallowing habits) improved our patient's symptoms, who has remained practically asymptomatic throughout the four years of follow-up.

In conclusion, when persistent intermittent dysphagia presents, dysphagia lusoria secondary to an ARSA should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Conservative treatment comprising a correction of dietary habits could significantly improve the symptoms of these patients.

Please cite this article as: Febrero B, Ríos A, Rodríguez JM, Parrilla P. Disfagia lusoria como diagnóstico diferencial de la disfagia intermitente. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:354–356.