This case study concerns an 83-year-old male with a prior history of hypertension and end-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (BCLC-D) in non-cirrhotic liver, receiving treatment with losartan. He had experienced three episodes of acute calculous cholecystitis in the previous 10 months. During the first and second admission, a percutaneous cholecystostomy was placed on both occasions and removed one month later after identifying a patent cystic duct on the cholangiography.

During the third admission, the patient experienced septic shock secondary to another episode of acute cholecystitis. A percutaneous cholecystostomy was performed, with clinical improvement and improved lab test results in the following days. Due to chronic cholecystitis and following the withdrawal of the percutaneous cholecystostomy, it was decided to perform palliative ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage with a Hot Axios® stent (Boston, 10×10mm) and a self-expandable double-pigtail plastic stent (7Fr/5cm), which was conducted without incident.

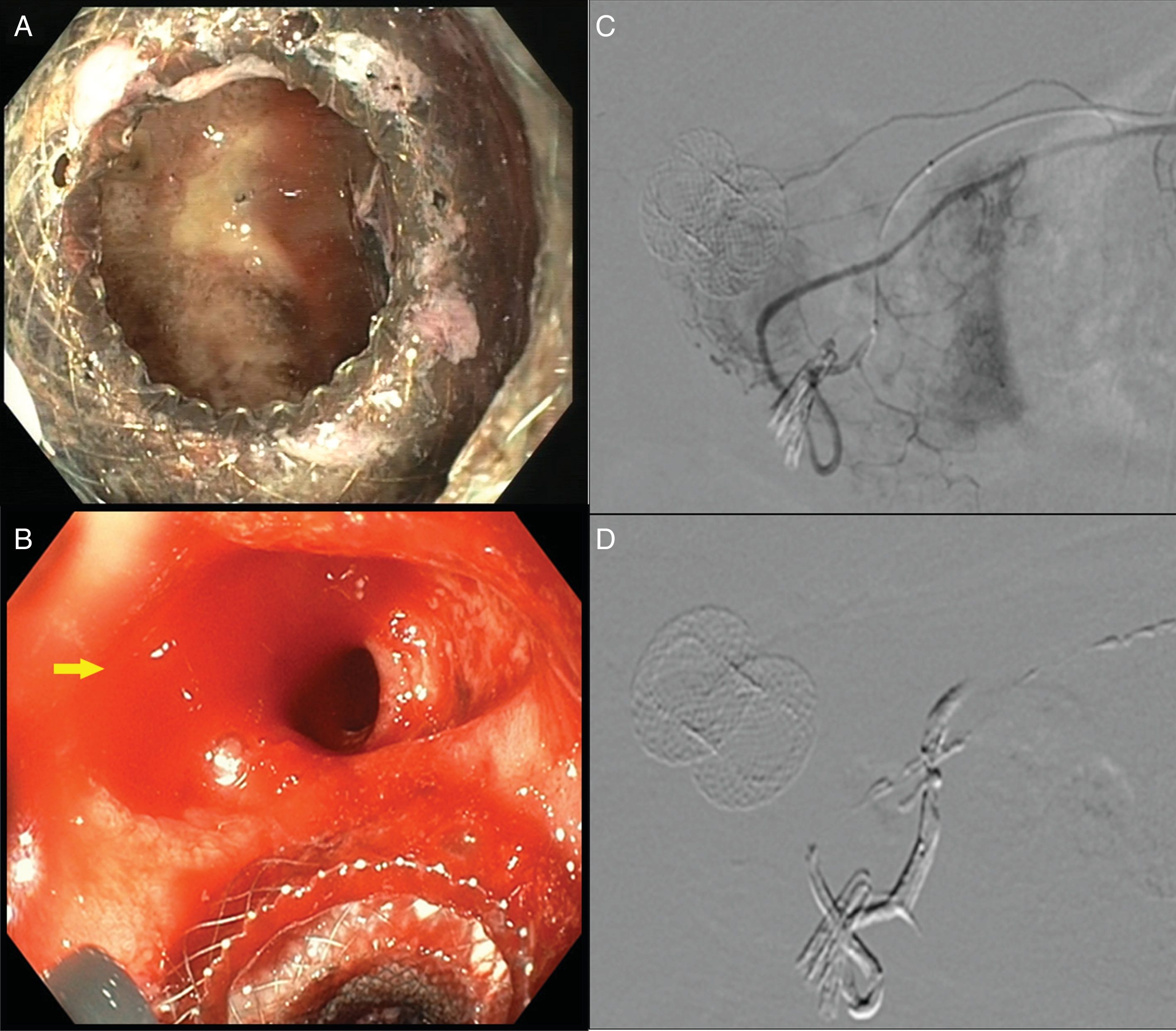

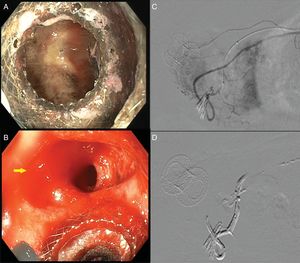

Four days after the procedure, he experienced an episode of gastrointestinal bleeding with marked anaemia (haemoglobin 11.9 to 5.5mg/dl), with no haemodynamic repercussions. The endoscopy revealed a 20-mm Forrest-IIC duodenal ulcer adjacent to the stent. Exploration of the inside of the gallbladder revealed two millimetric erosions with traces of haematin (Fig. 1A), which were sclerosed with adrenaline (1:20,000). Two days later, the patient experienced another bleeding episode with haemodynamic instability that did not abate despite intensive serum therapy. Another endoscopy was performed, which identified pulsatile bleeding in the duodenal ulcer, with no signs of bleeding in the gallbladder drainage (Fig. 1B). Conventional endoscopic treatment (adrenaline, Etoxiesclerol®, haemoclips) followed by the application of Hemospray® (Cook) was ineffective. Finally, an angiography was performed that revealed active bleeding of a branch of the gastroduodenal artery. This was effectively embolised with coils and Onyx liquid embolic agent (Fig. 1C and D), with no subsequent recurrence of bleeding. The patient remained hospitalised for a further 20 days and required six units of packed red blood cells to treat hypovolaemic shock. After six months of follow-up, the patient has experienced no further episodes of cholecystitis or stent-related complications despite it not having been withdrawn.

(A) Erosions in the gallbladder seen through the stent. (B) Duodenal ulcer with active bleeding (Forrest IA) in the vicinity of the stent. (C) Angiography of the coeliac trunk with active bleeding dependent on branches of the gastroduodenal artery. (D) Gastroduodenal artery after embolisation.

Although the standard treatment for serious acute cholecystitis is cholecystectomy, the placement of a percutaneous cholecystostomy is sometimes required in patients with significant comorbidity.1 Its withdrawal one month later should be contemplated as long-term placement is often associated with migration and infections.2 However, after its withdrawal, the risk of cholecystitis recurrence is up to 41%.2

Ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage is a relatively new treatment alternative.1 It involves the placement of a stent from the stomach or duodenum to the gallbladder to form a fistula and facilitate its drainage.1 In acute cholecystitis, the technical and clinical success rates are high and the number of complications is low (12.1%), particularly with the use of Axios® lumen-apposing metal stents.1 Another option is the internalisation of percutaneous cholecystostomy in patients who are unfit for surgery and with recurrent cholecystitis following the removal of the cholecystostomy.3 It has been suggested that this indication my pose greater technical difficulties3 due to: (1) Worse echogenicity, (2) Difficulty deploying the stent because the gallbladder does not distend sufficiently as it is percutaneously drained, and (3) Thickening and fibrosis of the gallbladder wall due to chronic cholecystitis. All of these factors could give rise to intra-procedural complications.3 However, from the two small studies that we found in the literature in which this internalisation was performed, only one complication was reported: bile leakage resolved by placing another stent.2,4 The rate of haemorrhagic complications seems to be low, and there is also the option to place an Axios® stent inside the gallbladder.5 Although uncommon, it is important to be aware of them as they may require the use of interventional radiology techniques for their effective control, as this case illustrates. In our case study, the source of the bleeding was not the gallbladder ulcers, but rather the duodenal ulcer, which may have been a pressure ulcer caused by the stent, or caused by the endoscopic procedure itself.

In contrast, cholecystitis recurrence is rare after gallbladder drainage.2 When it does arise, it is usually caused by the obstruction of the stent by gallstones.2 This can be endoscopically treated by extracting the stone or even removing the stent, as the formation of a cholecystoenteric fistula that can protect against cholecystitis has been observed.5

In conclusion, ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage is an effective technique to internalise percutaneous gallbladder drainage that improves patient quality of life. However, this procedure should be performed by experienced endoscopists due to the risk of serious complications.

Please cite this article as: Ríos León R, Martínez González J, Sánchez Rodríguez E, Foruny Olcina JR, Pérez-Miranda M, Crespo Pérez L, et al. Hemorragia digestiva tras una colecistoduodenostomía guiada por ecoendoscopia. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:376–377.