Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is uncommon, affecting an estimated one in 25,000 people. It is characterised by a deficiency in antibody production, and has a wide variety of clinical features.1 According to the largest European database, the main features were pneumonia (32%), autoimmunity (29%), splenomegaly (26%) and bronchiectasis (23%).2

This article looks at the case of a patient with CVID who had a cytomegalovirus (CMV) opportunistic infection which resolved satisfactorily after treatment with ganciclovir and an anti-TNF drug.

The patient was a 37-year-old female who was diagnosed with CVID 8 years earlier as a result of recurrent respiratory infections. She was being treated with immunoglobulins and B12 and was being monitored by the digestive disease department due to having chronic diarrhoea. This was determined to be caused by an immune process and not an infectious process, and was treated with corticosteroids, with a positive response.

She was admitted due to more severe diarrhoea (6–8bowel movements/day) without blood, mucus or pus that was associated with weight loss (10kg). Physical examination revealed: BMI of 17, distended abdomen, tender to touch, no rebound tenderness with normal bowel sounds.

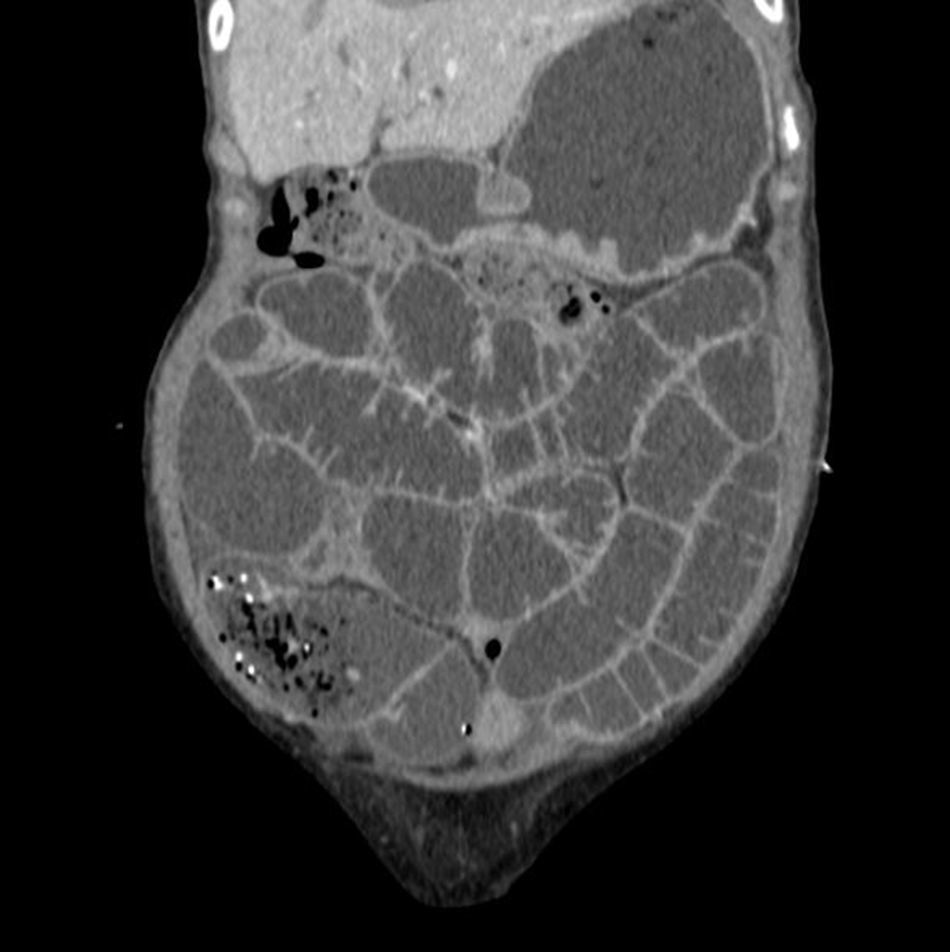

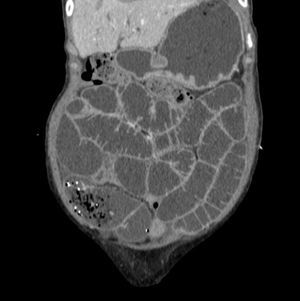

Lab tests, including stool cultures (×3), intestinal parasites (×3), C. difficile toxin (×3), auramine staining in stools, mycobacteria culture and Tropheryma whipplei PCR in saliva and stool specimens, were negative. An endoscopy and colonoscopy showed no abnormalities. However, the duodenal biopsy and random colon biopsies showed oedema and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the lamina propria. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, showing homogeneous hepatomegaly and splenomegaly and hypodense retroperitoneal and mesenteric lymphadenopathy greater than one centimetre in diameter (Fig. 1).

In view of the unfavourable clinical course, persistent diarrhoea and findings of retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly, we suggested a differential diagnosis of lymphoma as the entity responsible for the patient's clinical manifestations.

Given the lack of endoscopic ultrasound access to the lymphadenopathies, we decided to perform a laparoscopic mesenteric lymph node biopsy. The histology study, using haematoxylin–eosin staining, showed eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions surrounded by a halo, producing the characteristic owl's-eye appearance. This is compatible with invasive CMV infection.

Prior to routine immunoglobulin infusion, the patient had hypoalbuminaemia and hypogammaglobulinaemia with albumin levels of 2.90g/dl, gamma-globulin levels of 0.46g/dl (IgG: 594, IgA<20 and IgM<17mg/dl) and a positive CMV viral load in serum, 2895copies/ml, analysed by PCR in peripheral blood.

In view of these findings, treatment for CMV infection was started with ganciclovir for 5 days followed by valganciclovir until 21 days of treatment was completed. The patient showed clinical improvement and was therefore discharged.

Two weeks later, the patient was admitted again suffering from 4 to 5 bowel movements/day and a distended abdomen. Again, the stool tests (stool cultures, intestinal parasites and C. difficile) were negative and serum gamma-globulin levels showed no significant changes. The CMV viral load had decreased to 220copies/ml. It was decided to start treatment with an induction regimen of 5mg/kg of infliximab (weeks 0/2/6) followed by a maintenance dose every 8 weeks.

Upon discharge, the patient continued to attend the clinic for check-ups and showed a favourable clinical response with one bowel movement/day and a 5kg weight gain 8 weeks after starting treatment.

CVID is the most common primary immunodeficiency after selective IgA deficiency. Clinical symptoms start during the second and third decade of life, with no gender predisposition. It is characterised by recurrent infections, particularly of the respiratory tract.3 Gastrointestinal symptoms appear later, with the most common being diarrhoea, malabsorption, giardiasis, vitamin B12 deficiency, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly. Most cases also require an endoscopy with biopsy in order to reach a diagnosis. Duodenal histology abnormalities are difficult to evaluate in these patients due to bacterial overgrowth, which is common in CVID patients.4

CVID causes abnormalities in the differentiation of B-cells into plasma cells, which also affects T-cells. Due to dysregulation of the immune system, these patients are more susceptible to non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, gastrointestinal malignancies, autoimmune diseases, opportunistic infections and inflammatory bowel disease.5 The ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease observed in CVID have different features from usual, and are therefore defined as ulcerative colitis-like and Crohn's disease-like diseases. The fundamental difference is the lack of plasma cells, granulomas and giant cells.6

After ruling out an infectious origin, treatment of severe, corticosteroid-resistant enteropathy in CVID is not well established. Some cases have been described that have responded well to treatment with anti-TNF drugs, resulting in weight gain and improved quality of life.7,8

In exceptional cases, such as the case of our patient, treatment with anti-TNF drugs is justified due to the severity of symptoms and the absence of other pathological findings. The efficacy of the drug could be related to the high serum and tissue levels of TNF-α described in some patients with CVID. TNF-α has also been observed to increase CMV replication in vitro,9 which suggests that infliximab, as an anti-TNF drug, may inhibit CMV reactivation in vivo. This may explain our patient's favourable response to infliximab treatment.

Please cite this article as: Prieto Elordui J, Arreba Gonzalez P, Ortiz de Zarate Sagastagoitia J, Deiss Pascual L, Blanco Sampascual S, Baranda Martín A, et al. Infliximab como tratamiento de la enteropatía severa en un paciente con inmunodeficiencia común variable e infección por citomegalovirus. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:163–164.