In-hospital diarrhoea has a high impact on morbidity and mortality rates among hospitalised patients. Chemoprophylaxis with antibiotics in selected patients could be a cost-effective tool for prevention.

MethodsA prospective randomised, open-label study was conducted in a tertiary hospital in Mexico City, selecting patients at high risk of acquiring in-hospital diarrhoea and assigning them to a group taking metronidazole 500mg orally every 8h for seven days or an observation group. The primary endpoint was the presence of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) infection during the seven days of evaluation. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee. Registration number (11.2017) of 14 March 2017.

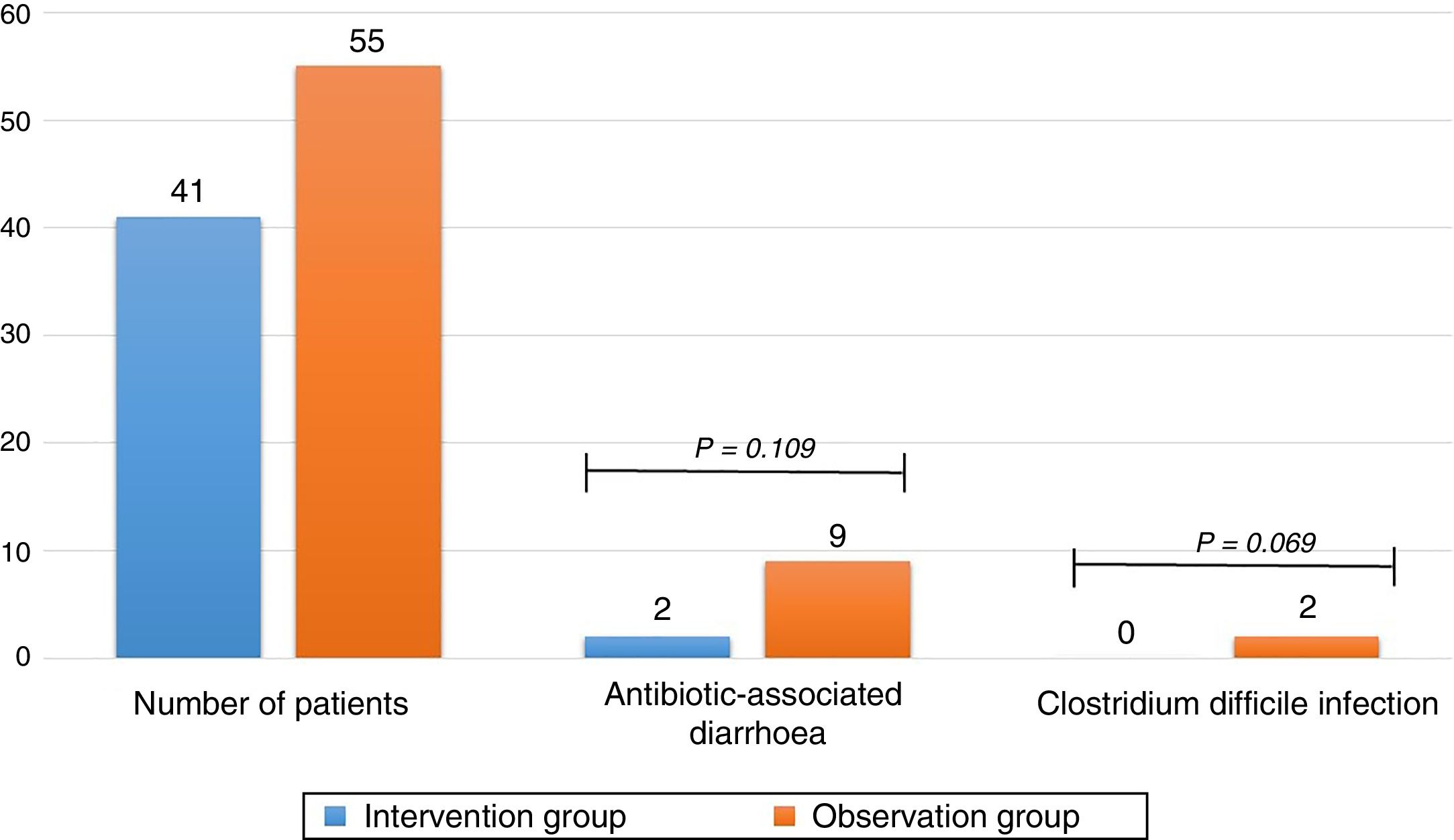

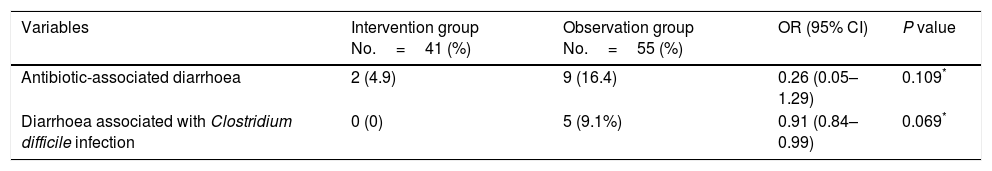

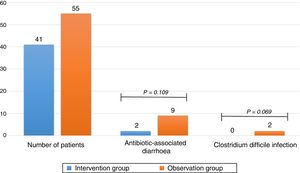

ResultsOf the 116 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 96 were analysed, 41 in the intervention group and 55 in the observation group: 4.9% of patients in the intervention group and 16.4% in the observation group developed antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (odds ratio [OR] 0.26 (0.05–1.29); P=0.109). 0% of patients in the intervention group and 9.1% in the observation group developed C. difficile infection (odds ratio [OR] 0.91 (0.84–0.99); P=0.069).

ConclusionsMetronidazole prophylaxis did not result in a reduction in antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. It could, however, be an effective measure for preventing C. difficile infection in selected high-risk patients. This was the first prospective study designed for this purpose. New studies that involve a larger number of patients are required in the future.

La aparición de diarrea intrahospitalaria supone un evento de alto impacto en la morbimortalidad de pacientes hospitalizados, la quimioprofilaxis con antibióticos en pacientes seleccionados podría resultar en una herramienta costo-efectiva para su prevención.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio prospectivo, randomizado, abierto, en un hospital de tercer nivel de la ciudad de México, seleccionando pacientes con alto riesgo de adquirir diarrea intrahospitalaria, se asignó pacientes a un grupo de metronidazol 500mg vía oral cada 8 h durante 7 días y un grupo de observación. El resultado primario fue determinar la presencia de diarrea asociada a antibióticos e infección por Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) durante los 7 días de evaluación. Aprobado por el comité de ética institucional. Número de registro (11.2017) del 14 de marzo de 2017.

ResultadosDe 116 pacientes que cumplieron criterios de inclusión, 96 fueron analizados, 41 en el grupo de intervención y 55 en el grupo de observación, la diarrea asociada a antibióticos se presentó en un 4,9% de pacientes en el grupo de intervención y en un 16,4% en el grupo de observación (odds ratio [OR] 0,26 (0,05-1,29) p = 0,109). La infección por C. difficile se presentó en el 0% de los pacientes en el primer grupo y en el 9,1% en el segundo grupo (odds ratio [OR] 0,91 (0,84-0,99) p = 0,069).

ConclusionesEl uso de metronidazol para prevención de diarrea asociada a antibióticos no se relacionó con disminución en su aparición, mientras que para infección por C. difficile podría resultar en una alternativa efectiva en seleccionados pacientes de alto riesgo. Éste es el primer estudio prospectivo diseñado para este fin. Se requieren a futuro nuevos estudios que involucren mayor número de pacientes.

The onset of intrahospital diarrhoea (IHD) represents an event with a high impact on mortality and morbidity, which increases costs and days of hospital stay. One factor which fosters its onset is the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.1 Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD) is a common disease in hospitalised patients. Its main mechanism is disruption of the intestinal flora with subsequent changes in carbohydrate metabolism, short-chain fatty acids and bile acids.2 It is usually a mild, self-limiting disease. However, 15–39% of cases are caused by Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) infection (CDI). These cases follow a more aggressive clinical course with high mortality.3

The first cases of CDI were reported in 1978.4 Since then, the incidence of this disease has shown a marked increase, with the appearance of new strains such as NAP1/BI/027, which have greater virulence and complications.5 The risk factors most commonly associated with its appearance in hospitalised patients are age >65 years, use of antibiotics (cephalosporins, clindamycin, beta-lactam antibiotics and fluoroquinolones) and suffering from serious diseases.6 Other additional factors include suppression of gastric acid, enteral nutrition, gastrointestinal surgery, obesity, chemotherapy, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and inflammatory bowel disease.7–9

Various measures to prevent its onset have been investigated, such as restricting prescription of antibiotics, particularly clindamycin, fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins10; washing hands with water and soap rather than alcohol-based disinfectants, which is associated with a greater likelihood of C. difficile eradication,11 mainly with the use of chlorhexidine-based soaps.12 Studies conducted with probiotics including a Lactobacillus combination have yielded variable results depending on the type and formulation used.13,14 Recently, a study evaluated the use of actoxumab and bezlotoxumab, which are human monoclonal antibodies against C. difficile toxins A and B, respectively. The study found bezlotoxumab, but not actoxumab, to be associated with a decreased rate of disease recurrence versus placebo.15

Chemoprophylaxis with drugs normally used in the treatment of the disease represents a reasonable, low-cost option to prevent the onset of the disease in patients screened as high-risk. Van Hise et al.16 conducted a retrospective study with the use of oral vancomycin to prevent the recurrence of CDI and found that recurrent CDI occurred in 4% of those who received prophylaxis versus 27% of those who did not. Regarding metronidazole, Rodríguez et al.17 retrospectively reported this medicine's efficacy in primary prevention in high-risk adult patients (defined as age 55 over years, use of a proton pump inhibitor and broad-spectrum antibiotics). The researchers found an incidence of 1.4% in the group of patients who received metronidazole for reasons other than CDI and 6.5% in the group of patients who did not. They concluded that receiving metronidazole reduces the incidence of intrahospital diarrhoea associated with C. difficile by 80%.

There are no prospective studies evaluating the effectiveness of these drugs as primary prevention of the onset of AAD and CDI in high-risk patients. One clinical trial with the use of metronidazole or placebo in patients at high risk of CDI was registered on the Clinical Trials platform. This study was not completed because the patients did not follow the instructions.18 The objective of this study is to evaluate the role of metronidazole in the prevention of AAD and CDI in high-risk hospitalised patients.

Materials and methodsStudy design and participantsA randomised, open-label clinical trial approved by the institutional ethics committee with registration number 11.2017 on 14 March 2017 was conducted. The trial enrolled patients hospitalised in the Internal Medicine department of Hospital Regional Licenciado Adolfo López Mateos in Mexico City from 1 May to 30 September 2017 who met the following inclusion criteria: age between 55 and 75 years (patients over 75 years of age were excluded due to a risk of enhancing possible adverse effects related to the use of other medicines)19,20; use of a proton pump inhibitor; use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, including one of the following: third-generation cephalosporins, levofloxacin and/or clindamycin (as these are those that are most often used at the institution); and a hospital stay less than 72h before the intervention. Patients were excluded if they had diarrhoea on admission, documented C. difficile infection in the past 6 months, altered mental state, use of metronidazole to treat a concomitant disease during hospitalisation, use of medicines with major interactions with metronidazole,21 pregnancy or alcohol consumption at least 48h before the intervention.22 All patients selected were invited to participate through an informed consent form. Patients who did not agree to take part, presented oral intolerance during the intervention, declined to continue taking the medicine or died due to causes unrelated to the onset of diarrhoea were eliminated.

RandomisationUsing a tool in the EXCEL program in the OFFICE 2013 suite, the patients selected were randomised to the intervention group with metronidazole 500mg PO every 8h for 7 days or to the observation group.

ProceduresOver the course of the 7 days following enrolment, the patients underwent follow-up to identify IHD. This was defined as three or more bowel movements with a diminished consistency (consistency 5–7 on the Bristol stool chart)23 in 24h. The endpoint was defined as IHD. Therefore, if the patients presented this, observation was stopped and the patients were treated according to institutional clinical practice guidelines. If they had IHD, the corresponding samples were collected and sent for testing for C. difficile toxins A and B. If the patients were discharged before they completed the 7 days of observation, the intervention group was given prescriptions for missing doses of metronidazole and both groups underwent follow-up by telephone in which they were asked whether or not they had diarrhoea. If they had diarrhoea, they were given an emergency appointment for sampling and assessment.

Statistical analysisThe trial was initially designed with sampling calculated with the difference formula for a total of 454 patients, 227 in each group, with an alpha error of 0.05 and a power of 80%, to detect a difference of 80% in the onset of AAD in both groups based on a study by Rodríguez et al.17 Due to institutional logistical matters, the desired sample size was not reached. In the end, 41 patients were enrolled in the intervention group and 55 patients were enrolled in the observation group. The data were exported from the study database and analysed using SPSS software (version 24). The variable of gender was analysed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Age had a normal distribution and was analysed using Student's t test. The variables of comorbidities, reasons for hospitalisation, prior hospitalisation and use of antibiotics during hospitalisation were analysed using the chi-squared test. The primary endpoint, the onset of AAD and CDI, was analysed using Fisher's exact test. Risk was calculated using contingency tables.

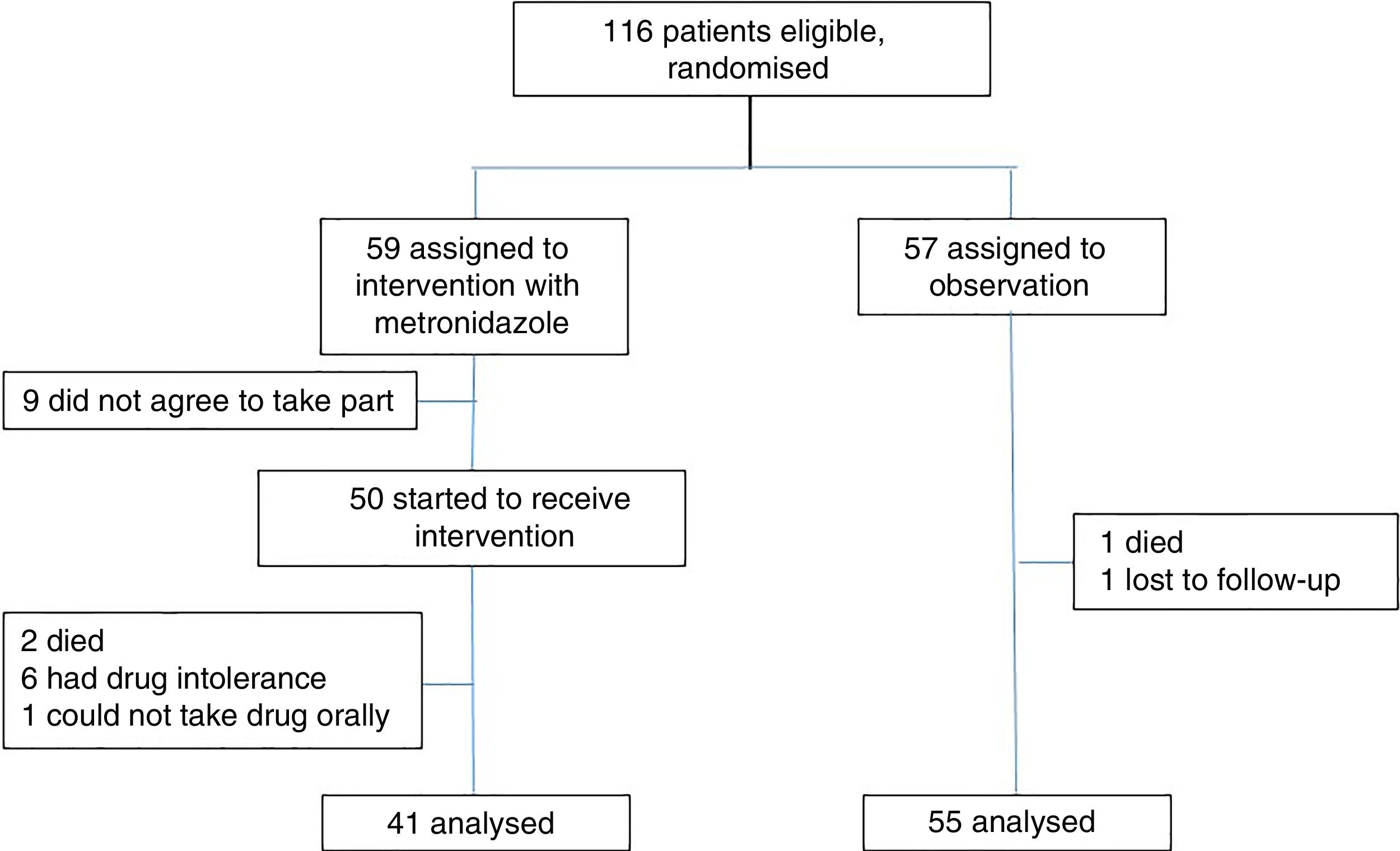

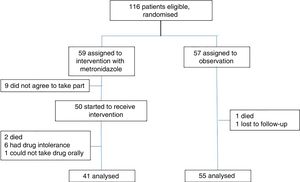

ResultsPatient recruitment took place from May to September 2017; 116 patients met the inclusion criteria. They were randomised and 59 patients were assigned to the intervention group. Of them, 9 did not agree to take part for fear of experiencing adverse effects that were previously known or experienced with the drug, and another 9 were excluded – 2 due to death; 6 due to adverse effects, predominately gastrointestinal adverse effects, headache and vertigo; and one due to medical indications for fasting. Ultimately, 41 patients were analysed. Fifty-seven patients were assigned to the observation group. One patient was excluded due to death and another was excluded due to loss of contact after discharge before the seventh day. In the end, 55 patients were analysed (Fig. 1).

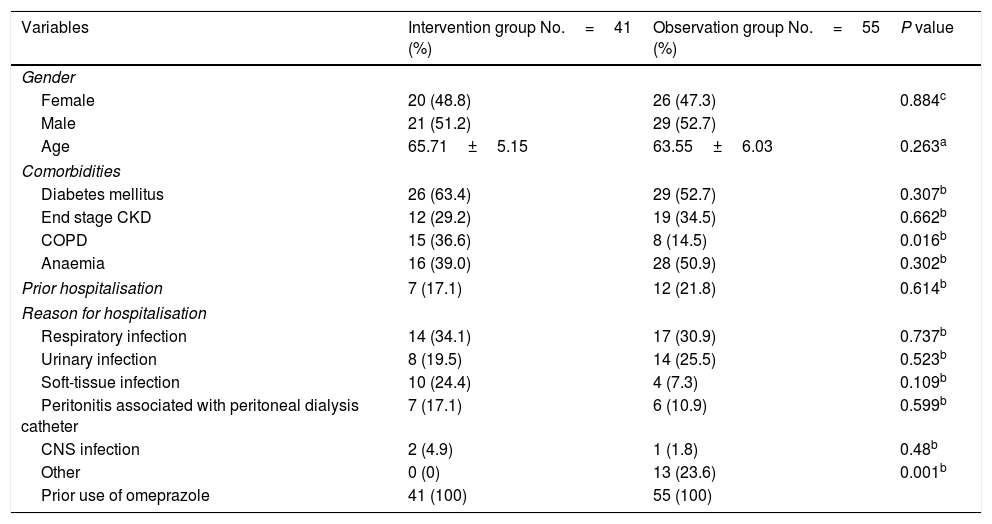

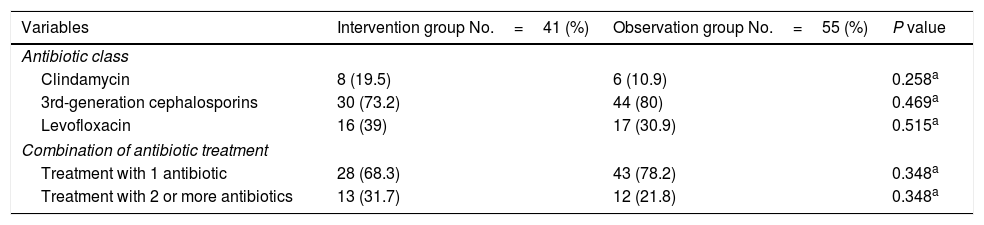

The patients randomised to the intervention group had a mean age of 65.71±5.15 years and 51.2% were men. The patients randomised to the observation group had a mean age of 63.55±6.03 years and 52.7% were men. The comorbidities evaluated were history of prior diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease (CKD) on renal replacement therapy using any modality and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). These were present in a substantial percentage of patients and distributed equitably between the two groups, with the exception of COPD, which was present in 36.6% of patients in the intervention group and just 14.5% of patients in the control group (p 0.016). Reasons for hospitalisation included respiratory infections, urinary tract infections, soft-tissue infection, peritonitis associated with peritoneal dialysis and central nervous system infection. These were distributed equitably between the two groups. Uncommon infectious diseases and diseases in which no focus of infection was documented were classified as “other causes”. Of the patients in the observation group, 23.6% received antibiotic treatment with no clear indication such as heart failure and electrolyte disorders. None of the patients in the intervention group was assigned to this category (Table 1). The antibiotics most commonly used in the patients evaluated were, in order of frequency, third-generation cephalosporins, levofloxacin and clindamycin. Depending on the medical indication, they were administered separately, and in a substantial percentage of patients (31.7% for the intervention group and 21.8% for the observation group), they were administered jointly. A logistic regression analysis did not find a relationship between this and a larger number of patients with AAD and CDI (Table 2).

Baseline characteristics of the population.

| Variables | Intervention group No.=41 (%) | Observation group No.=55 (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 20 (48.8) | 26 (47.3) | 0.884c |

| Male | 21 (51.2) | 29 (52.7) | |

| Age | 65.71±5.15 | 63.55±6.03 | 0.263a |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 26 (63.4) | 29 (52.7) | 0.307b |

| End stage CKD | 12 (29.2) | 19 (34.5) | 0.662b |

| COPD | 15 (36.6) | 8 (14.5) | 0.016b |

| Anaemia | 16 (39.0) | 28 (50.9) | 0.302b |

| Prior hospitalisation | 7 (17.1) | 12 (21.8) | 0.614b |

| Reason for hospitalisation | |||

| Respiratory infection | 14 (34.1) | 17 (30.9) | 0.737b |

| Urinary infection | 8 (19.5) | 14 (25.5) | 0.523b |

| Soft-tissue infection | 10 (24.4) | 4 (7.3) | 0.109b |

| Peritonitis associated with peritoneal dialysis catheter | 7 (17.1) | 6 (10.9) | 0.599b |

| CNS infection | 2 (4.9) | 1 (1.8) | 0.48b |

| Other | 0 (0) | 13 (23.6) | 0.001b |

| Prior use of omeprazole | 41 (100) | 55 (100) | |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease.

Antibiotic treatment by class and treatment group.

| Variables | Intervention group No.=41 (%) | Observation group No.=55 (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic class | |||

| Clindamycin | 8 (19.5) | 6 (10.9) | 0.258a |

| 3rd-generation cephalosporins | 30 (73.2) | 44 (80) | 0.469a |

| Levofloxacin | 16 (39) | 17 (30.9) | 0.515a |

| Combination of antibiotic treatment | |||

| Treatment with 1 antibiotic | 28 (68.3) | 43 (78.2) | 0.348a |

| Treatment with 2 or more antibiotics | 13 (31.7) | 12 (21.8) | 0.348a |

The primary finding of the study was that 16.4% of patients in the observation group and 4.9% in the intervention group had AAD with a P of 0.109 and an OR of 0.26 (0.05–1.29). The study was unable to establish a relationship between the administration of metronidazole and a lower number of patients with AAD. Regarding CDI, there were 5 cases found to be positive through testing for toxins A and B in the observation group and no cases in the intervention group, with a P of 0.069 and an OR of 0.91 (0.84–0.99) (Table 3). This suggested that the use of metronidazole is associated with a lower number of patients with CDI, although statistical significance was not achieved (Fig. 2).

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile infection.

Chemoprophylaxis with drugs normally used to treat CDI represented a promising cost-effective measure for high-risk patients in retrospective studies. This constitutes the first prospective study that evaluated the effectiveness of these drugs, normally used in the treatment of CDI, as a preventive measure in selected patients. It found that receiving metronidazole does not significantly prevent the onset of AAD. It also found that its use could be suggested as a preventive measure for CDI. It is important to note that this is a low-cost, easy-to-access drug that is widely used in multiple infections. Its many adverse effects, widely known by patients, limited the number of participants enrolled in the intervention group. Of those selected, 15.2% did not agree to enrol. To this was added 12% who started but did not finish taking the medicine as they experienced adverse effects, primarily of a gastrointestinal nature, as it is a very poorly tolerated drug. Furthermore, we do not know the effect of the drug on the intestinal microbiota or the extent to which its use generates bacterial resistance, which may interfere with its efficacy as a first-line treatment in CDI.

It is important to note that the population cared for at our centre had a high rate of comorbidities. In particular, CKD in peritoneal dialysis was present in close to a third and diabetes mellitus was present in nearly half of the patients selected. These triggered a significant number of cases of non-infectious diarrhoea, as a manifestation particular to the underlying diseases. A logistic regression analysis did not find these comorbidities to have a significant impact on the onset of AAD and CDI.

This study has significant limitations, such as its open-label nature, the limited number of patients enrolled and the high percentage of patients lost in the intervention group. Diagnosis of CDI was based on detection of C. difficile toxins A and B, which had high specificity (close to 100%) but low sensitivity.24 This might have caused the real number of patients with CDI to be underestimated, both in the intervention group and in the observation group. As these groups had such limited numbers of patients, small changes significantly impacted data analysis.

ConclusionsCDI constitutes a disease with a high impact on mortality, morbidity and costs of medical care. This prospective study evaluated the use of metronidazole in the prevention of both AAD and CDI. It did not find a significant relationship between its administration and a lower incidence of AAD. In CDI, the P value approached statistical significance with intervals that might suggest its use. However, low-sensitivity tests were used to diagnose the condition. Furthermore, the drug was found to be very poorly tolerated. Further studies are required with larger numbers of patients, double blinding and more effective diagnostic tests.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest for conducting this study. Metronidazole was provided by ISSSTE Hospital Regional Licenciado Adolfo López Mateos. Data collection and statistical analysis were performed with the authors’ own resources.

Please cite this article as: Tobar-Marcillo M, Guerrero-Duran M, Avecillas-Segovia A, Pacchiano-Aleman L, Basante-Díaz R, Vela-Vizcaino H, et al. Metronidazol en la prevención de diarrea asociada a antibióticos e infección por Clostridium difficile en pacientes hospitalizados de alto riesgo. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:362–368.