We present a case report of a 55-year-old man with a history of valvular heart disease, a pacemaker for atrial fibrillation with slow ventricular response, and anticoagulant therapy, monitored in a private clinic. A total of 6 episodes of uncomplicated acute diverticulitis in the previous 5 years had been treated conservatively with a good outcome. He was admitted to our department with a 48-hour history of diffuse, predominantly hypogastric abdominal pain that did not affect urination or bowel frequency. The patient had no fever or dysthermia. Blood tests taken in the emergency department showed elevated acute-phase reactants (C-reactive protein, 14.5mg/L; white cell count, 13,000/mm3 with 88% neutrophils), and an ultrasound scan revealed free fluid with normal bowel loops. Examination was remarkable for diffuse abdominal pain with signs of peritoneal irritation. An urgent computed tomography (CT) scan showed a thickened appendix and images suggestive of proximal small bowel obstruction. In view of these findings and given the signs of peritoneal irritation, assessment by the general surgery department was requested. Emergency surgery revealed serosanguineous ascites (cytology positive for malignant cells), with peritoneal implants disseminated throughout the entire peritoneal cavity. Gangrenous appendicitis was also detected, for which appendectomy was carried out. Several samples of the peritoneal implants were analyzed but no cause of obstruction could be identified. An episode of heart failure responded well to unloading therapy. The patient was referred to an outpatient oncology clinic on discharge a few days later. After assessment in outpatients, he chose to return to the private centre where his heart disease was being monitored and was started on treatment with cisplatin and gemcitabin. His disease is currently stable.

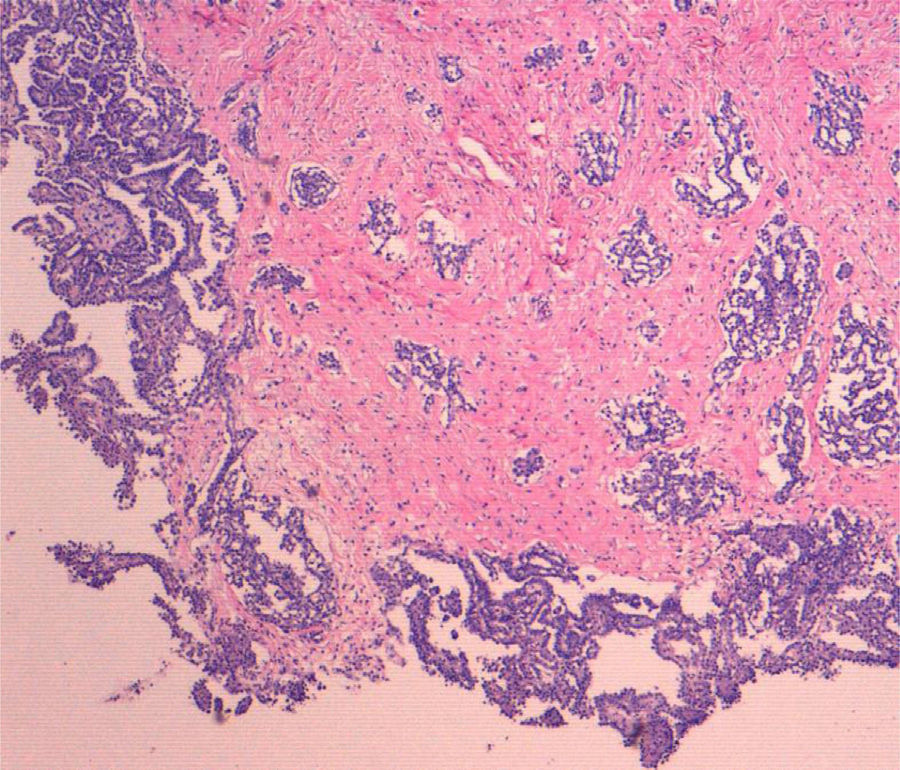

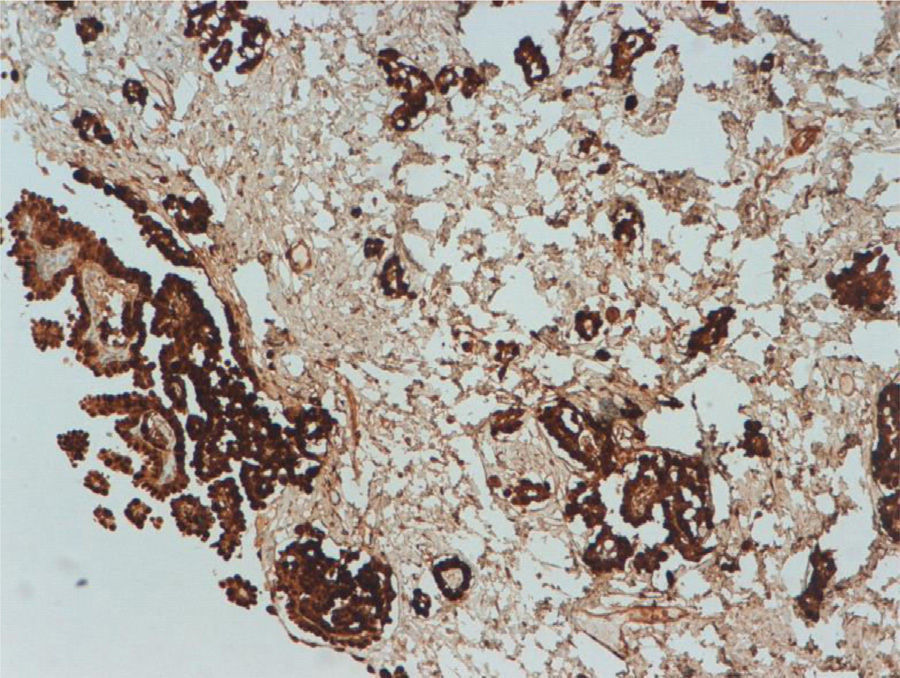

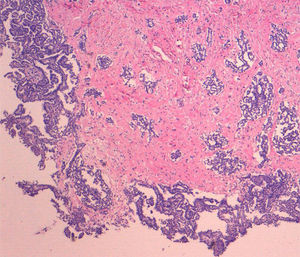

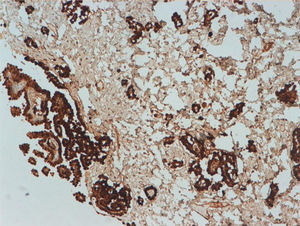

Both the appendectomy specimen and the mesenteric and peritoneal implants showed histology consistent with malignant epithelioid mesothelioma. Low power (4×) microscopy (Fig. 1) showed tumour proliferation forming papillae and invading the stroma, with reactive fibrosis at the level of the serosa of the mesenteric nodule. Higher power magnification (10×) showed cells with an epithelioid appearance and little evidence of atypia. Immunohistochemical staining for calretinin (Fig. 2) revealed intense, diffuse cytoplasmic staining of tumour cells, confirmed as mesothelial.

Malignant mesothelioma is a rare neoplasm which, in one third of cases,1 affects the peritoneum, with involvement primarily at the pleural level. Although the main risk factor for onset is exposure to asbestos, this disorder is also associated with familial Mediterranean fever and germline mutations in BRCA1-associated protein-1 (BAP1), as well as with radiation, exposure to other minerals and papovavirus infection.2 Although pleural mesothelioma predominantly affects men (4–5:1 ratio), the male–female ratio is more balanced for peritoneal mesothelioma: women accounted for 44% of 1112 peritoneal cases, compared to just 19% of pleural cases, included in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database of 10,589 cases of mesothelioma recorded between 1973 and 2005.3 Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma usually presents as chronic abdominal pain and ascites, with most cases characterized by gross, diffuse abdominal involvement. The mesothelioma is often masked by acute inflammatory processes–such as appendicitis,4 cholecystitis or incarcerated umbilical hernia–and so is only discovered during surgery; in other cases, the mesothelioma can only be seen at microscopic level.5 A study by Yan et al.6 showed that the presence of obstructive signs in imaging techniques such as CT predicted suboptimal surgical resection; this was the case with our patient, whose lesion could not be completely resected. Tumour markers such as CA-125 or CA 15.3 are elevated in approximately half of patients. Mesothelin is overexpressed in malignant mesothelioma. Soluble mesothelin-related peptides (SMRPs)–fragments or abnormal variants of mesothelin unable to bind to the membranes and so deposited in serum–appear to have some value as specific markers, and are also useful in monitoring patients already diagnosed with mesothelioma. Nevertheless, definitive diagnosis is made on the basis of histological analysis of the lesion.

Traditional treatment achieves survival rates ranging from 6 to 16 months,7 with surgery generally performed for palliative cytoreductive purposes. Although conventional systemic treatments fail to achieve good response rates,8 these have improved somewhat with the emergence of new agents like pemetrexed and gemcitabin. Treatments such as aggressive cytoreduction followed by intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy–while not free of morbidity–have lengthened survival. The best hope for future treatment of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma comes from recently discovered therapeutic targets such as sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1).

The fact that malignant peritoneal mesothelioma sometimes presents as an abdominal inflammatory process tentatively suggests a possible link between the peritoneal mesothelioma and our patient's previous episodes of diverticulitis.9 It is not uncommon to find a rare disease under the guise of a more common one, leading to a change in prognosis. Therefore, in cases like that of our patient, with recurrent inflammatory processes, diagnosis should take into account possibilities other than the more common disease. The fact that our patient had not been exposed to asbestos–a classic risk factor for this condition–combined with the rare form of presentation made early diagnosis of his mesothelioma even more difficult.

Please cite this article as: Valdivielso Cortázar E, Martínez Echeverría A, Fernández-Urién I, Llanos Chávarri MC, Vila Costas JJ, Jiménez Pérez FJ. Mesotelioma epitelioide peritoneal desenmascarado por una apendicitis aguda. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:217–218.