Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI), or the presence of gas in the interstitium of the bowel wall, is a radiological sign present in diseases of varying severity which involves several diagnostic and therapeutic approximations. We discuss the cases of 2 patients with Crohn's disease (CD) who presented with asymptomatic cystic PI as a CT scan finding, who made good progress after conservative treatment.

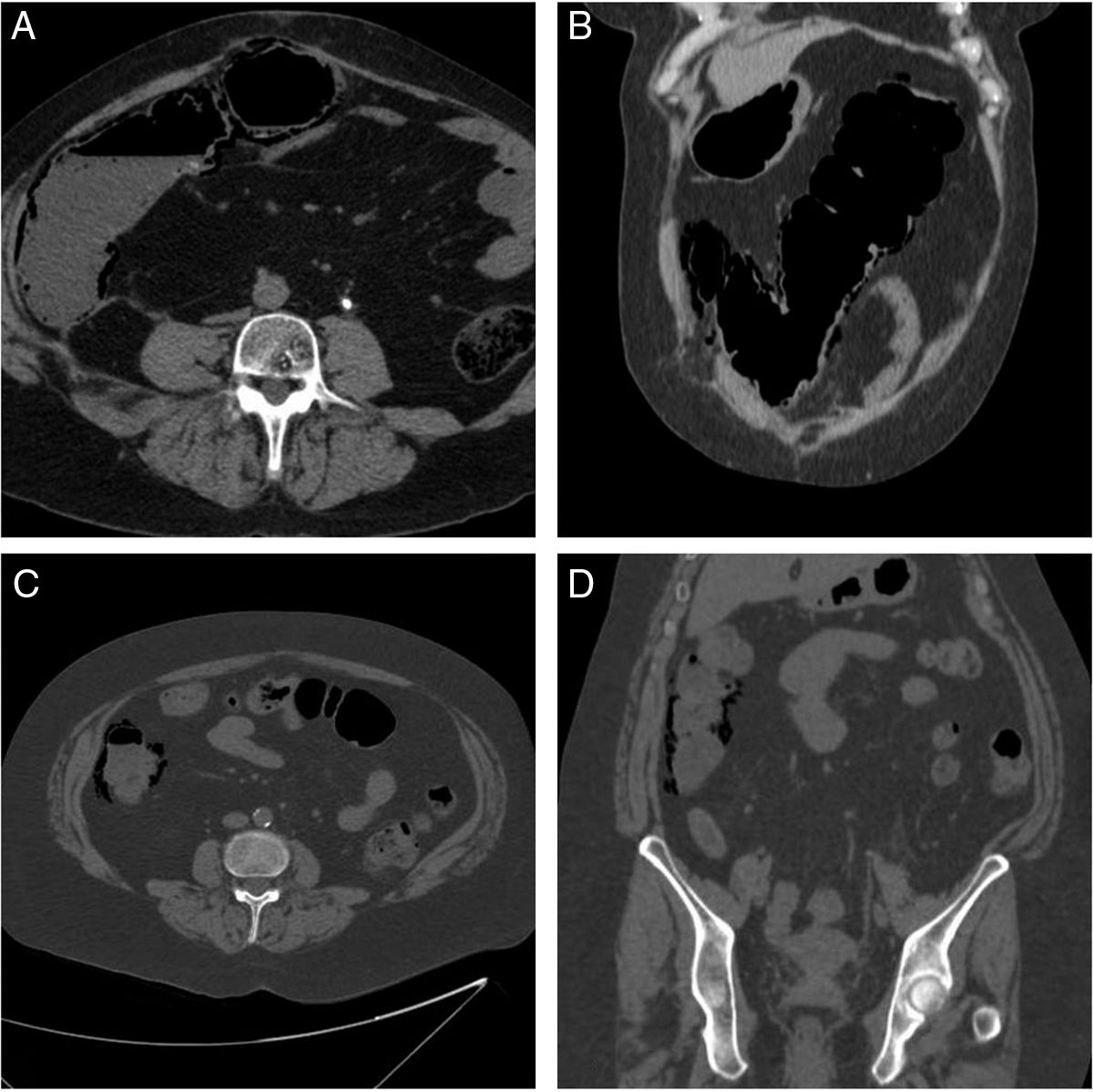

The first case concerns a 60-year-old female patient with long-standing fistulising CD (phenotype A2L3B3+P). She had taken various treatments which she abandoned because they were ineffective or due to side effects and required 2 ileocolic resections, one of them complicated by anastomotic dehiscence. Consequently, she herself decided to discontinue treatment, and her course was characterised by well-tolerated clinical signs and symptoms and very mild elevation of acute phase reactants. At the same time, she presented with signs and symptoms of renal and ureteral calculi which required a nephrostomy and placement of a double-J catheter. The findings on the follow-up CT scan included cystic PI in the ascending and transverse colon (Fig. 1). At the time, the patient only experienced her usual mild abdominal discomfort, with no peritoneal irritation. Alerted by the department of radiodiagnostics, we informed the patient and obtained laboratory test results which showed C-reactive protein (CRP) of 8mg/l (normal: <5), with no leukocytosis.

Case 1: axial (A) and coronal (B) slices from the abdominal and pelvic CT scan without contrast medium in which extensive pneumatosis intestinalis is observed in the ascending and transverse colon. Case 2: axial (C) and coronal (D) slices from the abdominal and pelvic CT scan without contrast medium in which pneumatosis intestinalis limited to the ascending colon is observed.

The second case involves a 58-year-old female patient with long-standing CD with strictures (phenotype A1L3B2) which required 2 ileal resections and treatment with Salazopirina® [sulfasalazine] and prednisone. These were followed by azathioprine, which was discontinued as she developed signs of portal hypertension. Subsequently, she took no treatment and experienced good clinical control. Over the course of her follow-up, the patient experienced repeated episodes of urolithiasis requiring the placement of a double-J catheter and a left nephrectomy, without subsequent recurrences. Three years later an abdominal CT scan was requested because of mechanical low back pain in which cystic PI was observed in the ascending colon (Fig. 1), resulting in her being referred to gastroenterology as an emergency case. At the time she was asymptomatic, and the laboratory tests showed CRP at 1.2mg/l (normal: <5), with no leukocytosis.

In both cases, the PI was considered a finding and was treated conservatively with clinical and radiological monitoring. Partial resolution of the episode was observed on the follow-up CT scans after three weeks and four months, respectively.

Historically, PI has been considered as a sign of severity associated with intestinal ischaemia. However, it can be secondary to highly diverse causes, including among others infection, inflammation and iatrogenic reasons.1 The generalisation of cross-sectional imaging techniques and their increased sensitivity have resulted in increased diagnoses of this radiological finding. This has led to a search for indicators which enable the image to be correlated with the severity of the underlying disease and to determine whether or not emergency surgery is required.

The theories most accepted to explain the onset of PI are bacterial, mechanical and pulmonary.2 PI is not a common finding in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but it has been described previously, sometimes as an endoscopic complication.3 A case-control study showed a higher incidence in patients with IBD than in the general population and was associated significantly with corticosteroid therapy.4 No association has been described between renal and ureteral calculi or manipulation of the urinary system and pneumatosis intestinalis, although this has been the case with abdominal surgery,5 which both patients required.

Abdominal pain and peritoneal irritation are among the clinical findings which correlate PI with intestinal ischaemia.5 In laboratory tests, lactic acid and CRP levels as well as leukocytosis are notable, although the degree of significance associated with each of these varied in the different studies.1,5

Concerning the radiological pattern, several authors have described the association between the linear pattern of PI and ischaemia respective of the benign nature of the cystic pattern.2 It has not been possible to correlate gas localisation or distribution with severity of the finding or underlying disease, although, generally, isolated colonic involvement is considered benign with respect to small intestine involvement. Other warning signs of ischaemia include reduced mural contrast enhancement, dilatation of the intestinal loops, ascites and mesenteric fat stranding.2

For management of idiopathic or benign PI there is consensus that clinical monitoring and personalised conservative treatment are sufficient.4 Hyperbaric oxygen therapy2 and antibiotic therapy with metronidazole4 have been suggested.

In conclusion, the onset of PI can occur in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. It is a radiological finding and not a clinical diagnosis, and as such should be interpreted in the context of its onset. There are various elements which can help us evaluate its severity and the need for emergency surgical intervention. When PI is considered a benign finding, conservative management under which patients show good clinical progress is adequate.

Please cite this article as: González-Olivares C, Palomera-Rico A, Romera-Pintor Blanca N, Sánchez-Aldehuelo R, Figueroa-Tubío A, García de la Filia I, et al. Neumatosis intestinal en la enfermedad de Crohn. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:182–183.