Pancreatic surgery in reference hospitals currently presents mortality rates below 5%, while morbidity varies between 18% and 52%.1–3 Post-pancreatectomy haemorrhage is among the most serious and feared postoperative complications, with an incidence of 2–18% and associated mortality of 15–68%.4 Among its many causes, the rupture of pseudoaneurysms (PS) that develop during the postoperative period is one of the most lethal and difficult to resolve surgically.

We present the clinical case of a 64-year-old patient with no history of interest, who presented with choluria and hypocholia with generalised pruritus and weight loss. Laboratory tests showed elevated bilirubin, while abdominal ultrasound revealed a hypoechoic area in the head of the pancreas with calcifications and dilatation of the common bile duct. After completing the computed tomography (CT) scan and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with biopsy, the patient was diagnosed with a neuroendocrine tumour of the head of the pancreas, subsequently undergoing cephalic duodenopancreatectomy with invaginated pancreaticogastric anastomosis.

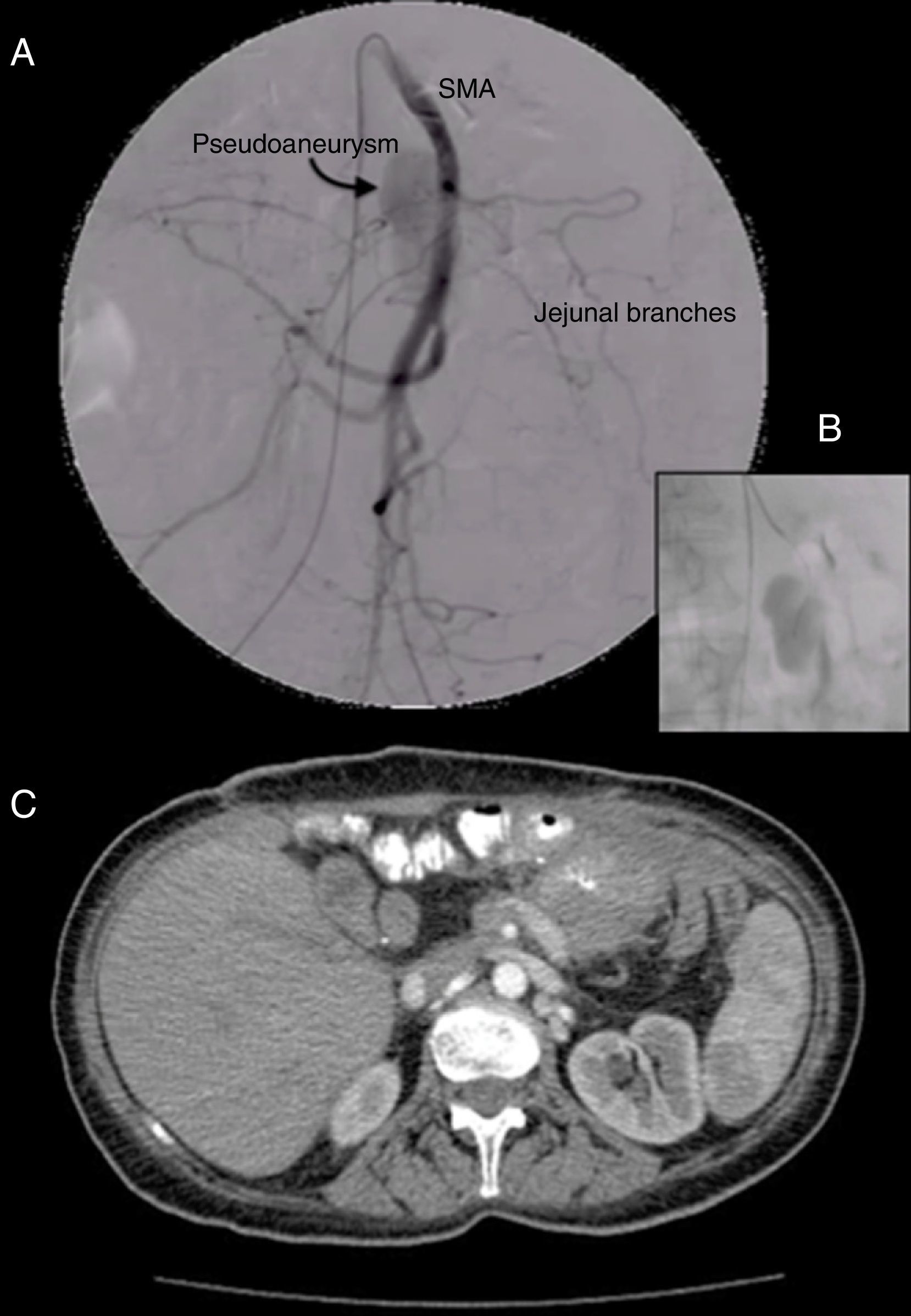

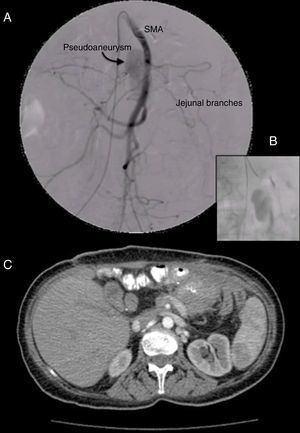

On postoperative day 14, he presented febrile syndrome and was diagnosed by CT scan with a left subdiaphragmatic and paracolic collection that was drained with percutaneous puncture. Ten days later, he experienced a sudden drop in haemoglobin to 7.2g/dL with a haematocrit of 23%—without becoming haemodynamically unstable—and was transfused with 3 units of packed red cells. An urgent CT scan revealed a mass with vascular enhancement adjacent to the superior mesenteric artery, consistent with a PS (Fig. 1). Arteriography confirmed the presence of a PS 3cm from the origin of the superior mesenteric artery, measuring around 4cm at its widest point, which was then embolised with thrombin (chosen as the emboligenic material due to the large size of the PS). As a small extravasation of thrombin towards the superior mesenteric artery was observed, angioplasty was also carried out, with the patient completely recovering vascular patency (Fig. 2). He was discharged 7 days later.

Arteriography and embolisation of the pseudoaneurysm: (A) Arteriography of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), identifying the pseudoaneurysm (arrow). (B) Detailed image of the catherisation and selective embolisation. (C) Follow-up computed tomography scan, in which the pseudoaneurysm can no longer be seen.

PS are rare but extremely serious complications, as they can cause an exsanguinating haemorrhage that is very difficult to treat should it rupture. They most often appear between 7 and 13 days postoperatively, although cases have been described after 28 days.5 This complication has been related with previous pancreatic fistula in up to 44% of cases.6 Risk factors that have been associated with the formation and rupture of PS are the presence of a pancreatic or biliary fistula, and intra-abdominal abscesses.7,8 During the pancreatectomy, the lymphadenectomy and skeletonisation of vascular structures makes the vessels more vulnerable to the pancreatic enzymes that can erode them and lead to the formation of PS. The possibility that surgical drains erode the vascular structures by mechanical pressure has also been suggested.3,4

The vessels where PS occur are usually—in order of frequency—the gastroduodenal artery stump, hepatic artery (or its branches) and the superior mesenteric artery.4 The splenic artery can also be affected, especially in cases in which the pancreatic reconstruction has been performed with pancreatogastrostomy.9

Treatment has usually been emergency laparotomy, but the problem with surgery is that the tissues are very inflamed and haemorrhage in the case of rupture is very profuse. This makes the intervention very difficult to perform when it comes to exploring the cavity, finding the bleeding site and ensuring good haemostasis, so much so that rebleeding and mortality rates exceed 60%.5

Transarterial embolisation (TE) consists in releasing intravascular elements (coils, thrombin, etc.) that cause blockage and coagulation of the bleeding site. TE has been shown to be successful in 86% of cases, reducing mortality to around 1%.5 Possible complications are rebleeding and ischaemia.3–6

In some territories, such as the superior mesenteric artery, embolising agents can cause distal ischaemia. In these cases, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-coated stents may be placed. On expansion, these occlude the vascular orifice responsible for the PS and enable good distal irrigation.3,10 However, the placement of coated stents in this area is technically more complex, so in our case we decided to fill the PS with thrombin, which is equally effective and technically more straightforward; the angioplasty was performed to ensure patency of the superior mesenteric artery after a small extravasation of emboligenic material was observed.

When compared with interventionist radiology procedures, surgical treatment has been associated with much higher mortality. Interventionist radiology techniques are more effective, less invasive, and result in lower mortality and morbidity, making them the first therapeutic option if the patient is stable and the appropriate measures are available.4

FundingNo funding or any type of assistance or grant was received for this study.

Please cite this article as: Ferro O, Soria J, Garcés M, Guijarro J, Gámez JM, Sabater L. Seudoaneurisma de la arteria mesentérica superior tras duodenopancreatectomía cefálica. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:400–402.