Real-world evidence on the adoption of different pharmacological strategies in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Latin America is scarce. Herein, we describe real-world sociodemographic, clinical characteristics, and different therapeutic approaches used in patients with IBD in Argentina.

MethodsRISE AR (NCT03488030) was a multicenter, non-interventional study with a cross-sectional evaluation and a 3-year retrospective chart review conducted in Argentina. Adult patients with a previous diagnosis of moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn's disease (CD) at least 6 months prior to enrollment were included.

ResultsThis study included 246 patients with IBD (CD: 41%; UC: 59%), with a median age of 39.5 years (IQR 30.7–51.7) for CD and 41.9 years (33.3–55.3) for UC. Overall, 51.5% of CD patients had colonic disease involvement, while 45.5% of UC patients had extensive colitis. At enrollment, the overall use of biologics was high, especially in CD patients (CD: 73.2% vs. UC: 30.3%, p<0.001), while the use of immunosuppressants was similar (∼41%, p=1.000) for both diseases. IBD treatments ever prescribed and healthcare resources utilization during the retrospective period were (CD, UC): biologics: 79.2%, 33.8% (p<0.001); immunosuppressants: 65.3%, 58.6% (p=0.352); aminosalicylates: 62.4%, 97.9% (p<0.001); corticosteroids: 55.4%, 69.7% (p=0.031); surgery: 17.8%, 1.4% (p<0.001); and hospitalizations: 33.7%, 21.4% (p=0.039).

ConclusionIn this cohort of IBD patients, overall prescription patterns of conventional therapy were similar to reports elsewhere; however, biologic therapy use was high, especially in CD, consistent with disease behavior and possibly reflecting better access to care in referral centers. Interestingly, over half of CD patients presented colonic involvement.

Existe limitada evidencia sobre el uso de terapias farmacológicas en la colitis ulcerosa (CU) o en la enfermedad de Crohn (EC) en el mundo real en América Latina. Aquí describimos las características sociodemográficas y clínicas, y los tratamientos utilizados en Argentina.

MétodosRISE-AR (NCT03488030) fue un estudio multicéntrico, no intervencional, transversal y retrospectivo (3años) de historias clínicas realizado en Argentina. Incluyó pacientes adultos con CU o EC de moderada a grave de ≥6meses a la fecha de enrolamiento.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 246 pacientes (EC: 41%; CU: 59%), con una mediana de edad de 39,5años (IQR: 30,7-51,7) para EC y de 41,9años (33,3-55,3) para CU. El 51,5% de los pacientes con EC presentaron afectación colónica, mientras que el 45,5% de los pacientes con CU tenían colitis extensa. Al enrolamiento, el uso de biológicos fue alto, especialmente en pacientes con EC (EC: 73,2% vs. CU: 30,3%, p<0,001), mientras que el uso de inmunosupresores fue similar (∼41%, p=1,000) para ambas enfermedades. Los tratamientos recibidos y la utilización de recursos de salud durante el período retrospectivo fueron (EC, CU): biológicos: 79,2%, 33,8% (p<0,001); inmunosupresores: 65,3%, 58,6% (p=0,352); aminosalicilatos: 62,4%, 97,9% (p<0,001); corticosteroides: 55,4%, 69,7% (p=0,031); cirugía: 17,8%, 1,4% (p<0,001), y hospitalizaciones: 33,7%, 21,4% (p=0,039).

ConclusiónEl uso de terapia convencional fue similar a lo reportado previamente; sin embargo, el uso de terapia biológica fue alto, especialmente en EC, consistente con el comportamiento de la enfermedad y posiblemente un mejor acceso al tratamiento en centros de referencia. Interesantemente, más de la mitad de los pacientes con EC presentaron afectación colónica.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic inflammatory disorders affecting the gastrointestinal tract characterized by alternating periods of remission and relapse.1 IBD generally refers to Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Both conditions pose a heavy burden on health, health-related quality of life and healthcare resources worldwide.

For the past two decades, the mainstream management of moderate to severe active IBD has been based on advanced therapies, initially with tumor necrosis factor antagonists (anti-TNF), but more recently, with the emergence of many other novel treatments (e.g., vedolizumab, ustekinumab, tofacitinib, ozanimod, upadacitinib), exhibiting different mechanisms of action and routes of administration. According to the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) initiative, the growing understanding of the physiopathology of IBD has served both patients and the medical community to aspire for more ambitious treatment outcomes to change the natural history of the disease.2 In a constantly evolving scenario, the management of IBD has certainly improved in recent years, but it has also become more complex from a therapeutic standpoint. Thus, the implementation of clinical guidelines remains a challenge in daily practice.

The incidence and prevalence of IBD are growing globally, especially in newly industrialized countries such as those in Latin America.3,4 Evidence on epidemiology and the adoption of different pharmacological strategies in IBD in the real-world setting in Argentina is scarce.5,6 Considering the impact that these pathologies have on patients’ health and healthcare systems, it is relevant to assess the therapeutic strategies used in real-world clinical practice to guide and optimize disease management and thus improve treatment outcomes.

The present study aimed to describe the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients with IBD and a previous diagnosis of moderate to severe IBD, and to assess pharmacological treatment patterns in the real-world clinical setting in Argentina.

Patients and methodsStudy design and participantsThe Real-world data of Moderate to Severe Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Argentina (RISE AR) study was a multicenter, non-interventional study with cross-sectional evaluation at enrollment and a 3-year retrospective chart review (NCT03488030). Patients were recruited from seven referral sites in Argentina, between December 2018 and May 2019. At each site, eligible patients were identified consecutively, as they attended a scheduled clinical appointment with their physician. Patients aged ≥18 years were included upon written informed consent, if they were diagnosed with moderate to severe CD or UC for at least 6 months prior to enrollment, regardless of disease activity at that moment. CD or UC diagnosis was based on clinical, endoscopic, histologic, or imaging criteria. Patients with indeterminate colitis or unclassified IBD, those participating in an IBD-related clinical trial during the observation period, or those presenting with mental incapacity, unwillingness to comply with the study protocol, or language barriers precluding adequate understanding of or cooperation with the study protocol, were excluded.

Data variablesSociodemographic characteristics (gender, age), clinical characteristics (body mass index, smoking status, time since IBD diagnosis, Montreal classification [i.e., location and severity/behavior], steroid behavior [dependent, refractory or responsive], family history of IBD and presence of extraintestinal manifestations [EIM], and other comorbidities) as well as the use of IBD treatments (aminosalicylates, immunosuppressants, biologics and corticosteroids) were collected from medical records. Biologics considered in this study were all biologial molecules approved for IBD as per label at the time the study was conducted (golimumab, certolizumab, infliximab adalimumab, and vedolizumab). IBD treatment duration was defined as the period (in months) between the initiation and the end of IBD therapy. For patients with ongoing IBD treatment at enrollment, the stop date was considered as the enrollment date. In addition, the cumulative treatment duration of each drug class was determined per patient as the sum of all treatment cycles per IBD drug class received during the retrospective period.

At enrollment, disease activity was evaluated according to the Harvey Bradshaw Index (HBI)7 for patients with CD and the 9-point scale partial Mayo score (pMayo) for patients with UC. For this study, we classified patients as having active disease (i.e., with moderate to severe disease activity) if presenting HBI ≥8 for patients with CD and pMayo score ≥5 for patients with UC.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the local ethics committees and was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration. This study was registered in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03488030).

Statistical analysisPatients were stratified based on their IBD condition (CD or UC). Descriptive statistics included proportions for categorical variables and mean±standard deviation (SD) or median and range (minimum, maximum) or interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables.

When comparing CD vs. UC treatments, categorical variables were assessed with the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, according to their frequency distributions. Continuous variables were analyzed using Students’ t test or Mann–Whitney test, depending on the homogeneity of variances. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA® software, version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, Texas, USA).

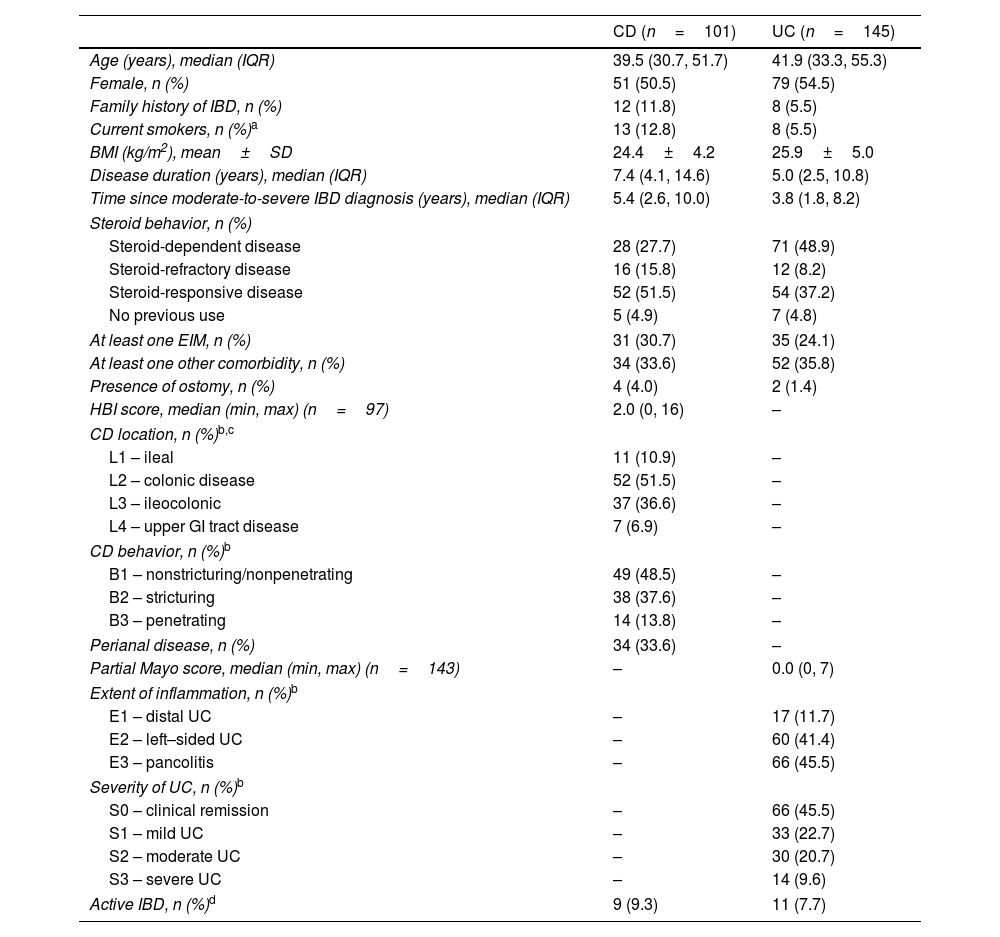

ResultsSociodemographic and clinical characteristics at enrollmentWe included 246 patients with IBD (CD: 41%; UC: 59%), with a median age of 39.5 years (IQR 30.7, 51.7) for CD and 41.9 (33.3, 55.3) for UC and a median (IQR) disease duration of 7.4 years (4.1, 14.6) for CD and 5.0 years (2.5, 10.8) for UC (Table 1). Most patients were female (CD: 50.5%; UC: 54.5%) (Table 1). Furthermore, 12.8% of patients with CD and 5.5% with UC were current smokers, and 11.8% of patients with CD and 5.5% of patients with UC had a family history of IBD. Nearly half of the patients with UC (48.9%) had steroid-dependent disease compared to less than one-third (27.7%) of patients with CD. EIMs were observed in 30.7% and 24.1% of patients with CD and UC, respectively; arthralgia (45.4%) was the most frequent manifestation in the overall cohort. Detailed information about EIMs and other comorbidities is described in Supplemental Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of IBD patients at enrollment.

| CD (n=101) | UC (n=145) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 39.5 (30.7, 51.7) | 41.9 (33.3, 55.3) |

| Female, n (%) | 51 (50.5) | 79 (54.5) |

| Family history of IBD, n (%) | 12 (11.8) | 8 (5.5) |

| Current smokers, n (%)a | 13 (12.8) | 8 (5.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean±SD | 24.4±4.2 | 25.9±5.0 |

| Disease duration (years), median (IQR) | 7.4 (4.1, 14.6) | 5.0 (2.5, 10.8) |

| Time since moderate-to-severe IBD diagnosis (years), median (IQR) | 5.4 (2.6, 10.0) | 3.8 (1.8, 8.2) |

| Steroid behavior, n (%) | ||

| Steroid-dependent disease | 28 (27.7) | 71 (48.9) |

| Steroid-refractory disease | 16 (15.8) | 12 (8.2) |

| Steroid-responsive disease | 52 (51.5) | 54 (37.2) |

| No previous use | 5 (4.9) | 7 (4.8) |

| At least one EIM, n (%) | 31 (30.7) | 35 (24.1) |

| At least one other comorbidity, n (%) | 34 (33.6) | 52 (35.8) |

| Presence of ostomy, n (%) | 4 (4.0) | 2 (1.4) |

| HBI score, median (min, max) (n=97) | 2.0 (0, 16) | – |

| CD location, n (%)b,c | ||

| L1 – ileal | 11 (10.9) | – |

| L2 – colonic disease | 52 (51.5) | – |

| L3 – ileocolonic | 37 (36.6) | – |

| L4 – upper GI tract disease | 7 (6.9) | – |

| CD behavior, n (%)b | ||

| B1 – nonstricturing/nonpenetrating | 49 (48.5) | – |

| B2 – stricturing | 38 (37.6) | – |

| B3 – penetrating | 14 (13.8) | – |

| Perianal disease, n (%) | 34 (33.6) | – |

| Partial Mayo score, median (min, max) (n=143) | – | 0.0 (0, 7) |

| Extent of inflammation, n (%)b | ||

| E1 – distal UC | – | 17 (11.7) |

| E2 – left–sided UC | – | 60 (41.4) |

| E3 – pancolitis | – | 66 (45.5) |

| Severity of UC, n (%)b | ||

| S0 – clinical remission | – | 66 (45.5) |

| S1 – mild UC | – | 33 (22.7) |

| S2 – moderate UC | – | 30 (20.7) |

| S3 – severe UC | – | 14 (9.6) |

| Active IBD, n (%)d | 9 (9.3) | 11 (7.7) |

BMI: body mass index; CD: Crohn's disease; CDAI: Crohn's Disease Activity Index; EIM: extraintestinal manifestation; GI: gastrointestinal; HBI: Harvey Bradshaw Index; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; max: maximum; min: minimum; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; UC: ulcerative colitis.

Percentages are calculated for the total population.

In UC, 45.5% and 41.4% of the patients had extensive colitis and left-sided colitis, respectively. Approximately two-thirds of patients with UC were in remission or presented with mild disease (S0: 45.5%; S1: 22.7%) (Table 1). In CD, 51.5% and 36.6% of patients presented with colonic and ileocolonic disease involvement, respectively, and 6.9% had upper gastrointestinal tract involvement. Over half of the patients with CD had non-inflammatory behavior (37.6% stricturing; 13.8% penetrating), and 33.6% presented with perianal disease (13.9% as B1p), resulting in a total of 65.3% patients with complicated disease. Detailed information on UC and CD location and behavior is described in Table 1.

At enrollment, 9.3% of patients with CD and 7.7% of patients with UC had active disease, which was defined as HBI≥8 or pMayo score≥5, respectively. Of note, 6 patients presented with ostomy, thus, disease activity could not be assessed. The median (range) HBI score was 2.0 (0, 16) for patients with CD, while the median (range) pMayo score was 0.0 (0, 7) for patients with UC (Table 1).

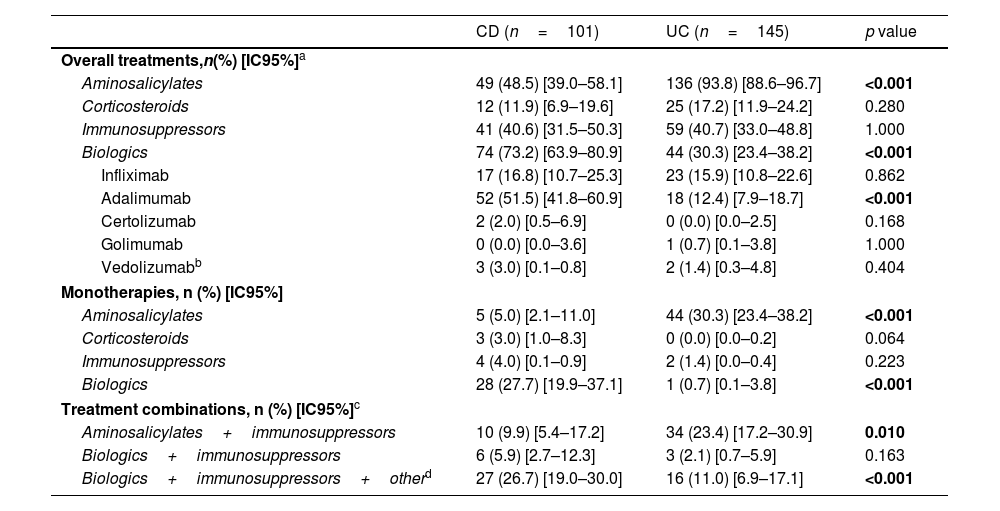

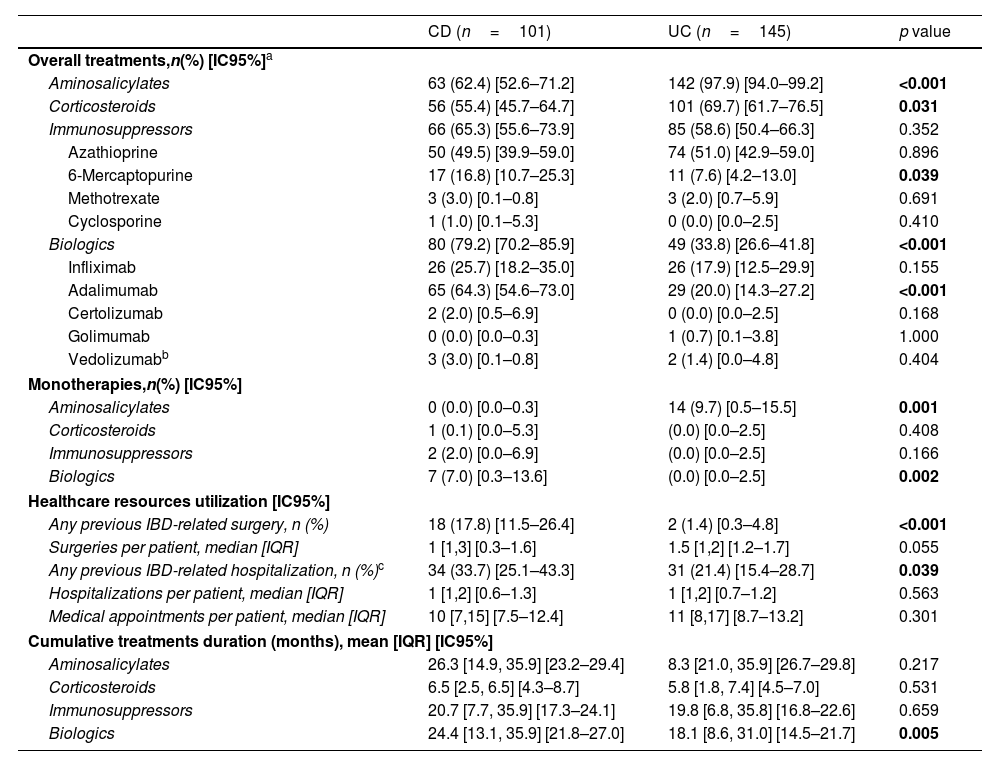

IBD treatment patterns at enrollment and during the previous 3 yearsAt enrollment, aminosalicylates were used broadly, particularly in UC (UC: 93.8%, CD: 48.5%, p<0.001) (Table 2), and nearly one-third of patients with UC (30.3%) were on monotherapy with this medication. During the retrospective period, most patients with UC (97.9%) were prescribed aminosalicylates compared with 62.4% of patients with CD (p<0.001) (Table 3); the majority of patients with CD who received a prescription had colonic involvement.

IBD treatment patterns at enrollment.

| CD (n=101) | UC (n=145) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall treatments,n(%) [IC95%]a | |||

| Aminosalicylates | 49 (48.5) [39.0–58.1] | 136 (93.8) [88.6–96.7] | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroids | 12 (11.9) [6.9–19.6] | 25 (17.2) [11.9–24.2] | 0.280 |

| Immunosuppressors | 41 (40.6) [31.5–50.3] | 59 (40.7) [33.0–48.8] | 1.000 |

| Biologics | 74 (73.2) [63.9–80.9] | 44 (30.3) [23.4–38.2] | <0.001 |

| Infliximab | 17 (16.8) [10.7–25.3] | 23 (15.9) [10.8–22.6] | 0.862 |

| Adalimumab | 52 (51.5) [41.8–60.9] | 18 (12.4) [7.9–18.7] | <0.001 |

| Certolizumab | 2 (2.0) [0.5–6.9] | 0 (0.0) [0.0–2.5] | 0.168 |

| Golimumab | 0 (0.0) [0.0–3.6] | 1 (0.7) [0.1–3.8] | 1.000 |

| Vedolizumabb | 3 (3.0) [0.1–0.8] | 2 (1.4) [0.3–4.8] | 0.404 |

| Monotherapies, n (%) [IC95%] | |||

| Aminosalicylates | 5 (5.0) [2.1–11.0] | 44 (30.3) [23.4–38.2] | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroids | 3 (3.0) [1.0–8.3] | 0 (0.0) [0.0–0.2] | 0.064 |

| Immunosuppressors | 4 (4.0) [0.1–0.9] | 2 (1.4) [0.0–0.4] | 0.223 |

| Biologics | 28 (27.7) [19.9–37.1] | 1 (0.7) [0.1–3.8] | <0.001 |

| Treatment combinations, n (%) [IC95%]c | |||

| Aminosalicylates+immunosuppressors | 10 (9.9) [5.4–17.2] | 34 (23.4) [17.2–30.9] | 0.010 |

| Biologics+immunosuppressors | 6 (5.9) [2.7–12.3] | 3 (2.1) [0.7–5.9] | 0.163 |

| Biologics+immunosuppressors+otherd | 27 (26.7) [19.0–30.0] | 16 (11.0) [6.9–17.1] | <0.001 |

CD: Crohn's disease; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; UC: ulcerative colitis.

Statistically significant differences are shown in bold. Percentages are calculated for the total population. Ongoing IBD treatments, including those with the start date equal to the enrollment date (i.e., treatment initiations).

IBD treatment patterns and use of healthcare resources in the 3-year retrospective period.

| CD (n=101) | UC (n=145) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall treatments,n(%) [IC95%]a | |||

| Aminosalicylates | 63 (62.4) [52.6–71.2] | 142 (97.9) [94.0–99.2] | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroids | 56 (55.4) [45.7–64.7] | 101 (69.7) [61.7–76.5] | 0.031 |

| Immunosuppressors | 66 (65.3) [55.6–73.9] | 85 (58.6) [50.4–66.3] | 0.352 |

| Azathioprine | 50 (49.5) [39.9–59.0] | 74 (51.0) [42.9–59.0] | 0.896 |

| 6-Mercaptopurine | 17 (16.8) [10.7–25.3] | 11 (7.6) [4.2–13.0] | 0.039 |

| Methotrexate | 3 (3.0) [0.1–0.8] | 3 (2.0) [0.7–5.9] | 0.691 |

| Cyclosporine | 1 (1.0) [0.1–5.3] | 0 (0.0) [0.0–2.5] | 0.410 |

| Biologics | 80 (79.2) [70.2–85.9] | 49 (33.8) [26.6–41.8] | <0.001 |

| Infliximab | 26 (25.7) [18.2–35.0] | 26 (17.9) [12.5–29.9] | 0.155 |

| Adalimumab | 65 (64.3) [54.6–73.0] | 29 (20.0) [14.3–27.2] | <0.001 |

| Certolizumab | 2 (2.0) [0.5–6.9] | 0 (0.0) [0.0–2.5] | 0.168 |

| Golimumab | 0 (0.0) [0.0–0.3] | 1 (0.7) [0.1–3.8] | 1.000 |

| Vedolizumabb | 3 (3.0) [0.1–0.8] | 2 (1.4) [0.0–4.8] | 0.404 |

| Monotherapies,n(%) [IC95%] | |||

| Aminosalicylates | 0 (0.0) [0.0–0.3] | 14 (9.7) [0.5–15.5] | 0.001 |

| Corticosteroids | 1 (0.1) [0.0–5.3] | (0.0) [0.0–2.5] | 0.408 |

| Immunosuppressors | 2 (2.0) [0.0–6.9] | (0.0) [0.0–2.5] | 0.166 |

| Biologics | 7 (7.0) [0.3–13.6] | (0.0) [0.0–2.5] | 0.002 |

| Healthcare resources utilization [IC95%] | |||

| Any previous IBD-related surgery, n (%) | 18 (17.8) [11.5–26.4] | 2 (1.4) [0.3–4.8] | <0.001 |

| Surgeries per patient, median [IQR] | 1 [1,3] [0.3–1.6] | 1.5 [1,2] [1.2–1.7] | 0.055 |

| Any previous IBD-related hospitalization, n (%)c | 34 (33.7) [25.1–43.3] | 31 (21.4) [15.4–28.7] | 0.039 |

| Hospitalizations per patient, median [IQR] | 1 [1,2] [0.6–1.3] | 1 [1,2] [0.7–1.2] | 0.563 |

| Medical appointments per patient, median [IQR] | 10 [7,15] [7.5–12.4] | 11 [8,17] [8.7–13.2] | 0.301 |

| Cumulative treatments duration (months), mean [IQR] [IC95%] | |||

| Aminosalicylates | 26.3 [14.9, 35.9] [23.2–29.4] | 8.3 [21.0, 35.9] [26.7–29.8] | 0.217 |

| Corticosteroids | 6.5 [2.5, 6.5] [4.3–8.7] | 5.8 [1.8, 7.4] [4.5–7.0] | 0.531 |

| Immunosuppressors | 20.7 [7.7, 35.9] [17.3–24.1] | 19.8 [6.8, 35.8] [16.8–22.6] | 0.659 |

| Biologics | 24.4 [13.1, 35.9] [21.8–27.0] | 18.1 [8.6, 31.0] [14.5–21.7] | 0.005 |

CD: Crohn's disease; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IQR: interquartile range; UC: ulcerative colitis.

Number of patients receiving at least one prescription of the different medications during the retrospective period. Percentages are calculated for the total population. Statistically significant differences are shown in bold.

Corticosteroids were the least frequently prescribed treatments at enrollment (UC: 17.2%, CD: 11.9%) (Table 2), in line with disease activity, where less than 10% of patients presented with active disease at study entry. During the retrospective period, corticosteroids were prescribed more frequently in patients with UC than in patients with CD (69.7% vs. 55.4%, p=0.031) but the mean [IQR] treatment duration (months) was similar for both conditions (CD: 6.5 [2.5, 6.5], UC: 5.8 [1.8, 7.4], p=0.531) (Table 3).

The overall use of biologic therapy was high, especially in patients with CD compared with patients with UC (at enrollment: 73.2% vs. 30.3%, p<0.001; retrospective period: 79.2% vs. 33.8%, p<0.001) (Tables 2 and 3). At enrollment, approximately one-third of patients with CD (27.7%) received biologic therapy as monotherapy compared with less than 1% of patients with UC (p<0.001) (Table 2). Among the biologic therapies, subcutaneous anti-TNF use was significantly more common in CD than UC (at enrollment: 73.0% vs. 43.2%, p<0.001); retrospective period: 83.7% vs. 61.2%, p<0.001) (Tables 2 and 3). During the retrospective period, 17.5% of patients with CD (n=14/80) and 16.3% of patients with UC (n=8/49) who were ever prescribed a biologic required more than one biologic treatment (data not shown), and the mean [IQR] treatment duration (months) was significantly longer in patients with CD compared to UC (CD: 24.4 [13.1, 35.9], UC: 18.1 [8.6, 31.0], p<0.01) (Table 3). Vedolizumab utilization was limited to 5 patients (CD: n=3; UC: n=2) as the agent became commercially available in Argentina during study enrollment. No patients were administered ustekinumab or tofacitinib as those agents were not commercially available during study enrollment.

At enrollment, the use of immunosuppressants was common, with a similar prevalence (CD: 40.6%, UC: 40.7%, p=1.000) for both UC and CD. However, immunosuppressants were rarely used as monotherapy (CD: 4.0%, UC: 1.4%) (Table 2). During the retrospective period, the overall frequency of immunosuppressant utilization was 65.3% in CD and 58.6% in UC (p=0.352) (Table 3); the mean [IQR] immunosuppressants treatment duration (months) was similar for both diseases (CD: 20.7 [7.7, 35.9], UC: 19.8 [6.8, 35.8], p=0.659) (Table 3). During the previous 3 years, azathioprine was the most commonly used immunosuppressant (CD: 75.8%, UC: 87.1%), followed by 6-mercaptopurine (CD: 25.8%, UC: 12.9%). Overall, fewer than 10 patients were prescribed methotrexate or cyclosporine (Table 3).

Over 40% of patient with IBD on a biologic were receiving concomitant immunosuppressants at enrollment (CD: n=33/74, 44.6%; UC: n=16/44, 43.2%, p=1.000) (Table 2). Infliximab was more frequently combined with immunosuppressants than adalimumab, although this was not statistically significant (CD: 52.9% vs. 30.8%, p=0.098; UC: 47.8% vs. 22.2%, p=0.091). Detailed information on treatment patterns is summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

IBD treatment discontinued in the 3-years retrospective period.

| CD (n=101) | UC (n=145) | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment discontinuations, n (%) | 80 (79.2) | 140 (96.6) |

| Aminosalicylates, n (%)a | 23 (28.8) | 92 (65.7) |

| Safety concerns | 1 (4.3) | 3 (3.3) |

| Poor effectiveness | 7 (30.4) | 16 (17.4) |

| Patient adherence | 1 (4.3) | 22 (23.9) |

| Remission | 4 (17.4) | 10 (10.9) |

| Expected end of treatment | 10 (43.5) | 41 (44.6) |

| Immunosuppressors, n (%)a | 28 (35.0) | 31 (22.1) |

| Safety concerns | 15 (53.6) | 16 (51.6) |

| Poor effectiveness | 8 (28.6) | 6 (19.4) |

| Patient adherence | 2 (7.1) | 5 (16.1) |

| Remission | 1 (3.6) | 4 (12.9) |

| Expected end of treatment | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Biologics, n (%)a | 29 (36.3) | 17 (12.1) |

| Safety concerns | 5 (17.2) | 2 (11.8) |

| Poor effectiveness | 17 (58.6) | 10 (58.8) |

| Surgery | 4 (13.8) | 1 (5.9) |

| Patient adherence | 1 (3.4) | 3 (1.6) |

| Remission | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Expected end of treatment | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) |

CD: Crohn's disease; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; UC: ulcerative colitis.

Number of patients discontinuing at least one prescription of the different medications during the retrospective period. Reasons for discontinuation related to access to medication were not included.

During the previous 3 years, a higher proportion of patients with CD compared with UC underwent surgery (17.8% vs. 1.4%, p<0.001); similarly, the need for hospitalizations (>24h) was greater among patients with CD compared with UC (33.7% vs. 21.4%, p=0.039). The median [IQR] of medical appointments during the retrospective period was similar between the groups (CD: 10.0 [7,15], UC: 11.0 [8,17], p=0.301) (Table 3). Nevertheless, median [IQR] disease duration (months) since IBD diagnosis and since moderate to severe disease diagnosis were significantly longer in patients with CD (CD: 7.4 [4.1, 14.6] vs. UC: 5.0 [2.5, 10.8], p=0.016; CD: 5.4 [2.6, 10.0] vs. UC: 3.8 [1.8, 8.2], p=0.024, respectively) (Table 1).

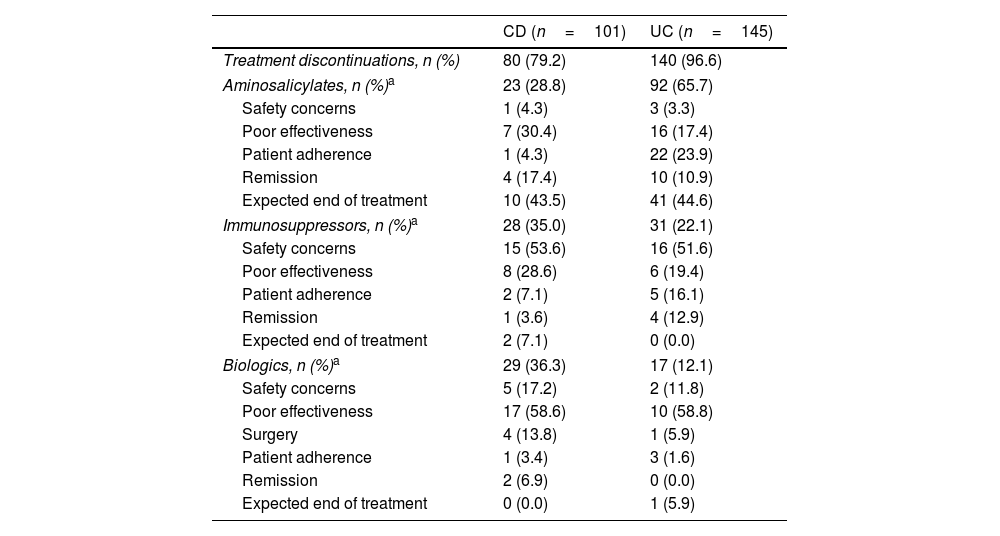

IBD treatment discontinuations during the previous 3 yearsNearly three-quarters of patients with CD (79.2%, n=80/101) and most patients with UC (96.6%, n=140/145) discontinued at least one IBD treatment during the retrospective period (Table 4). Within all cases of treatment discontinuation, the proportion of patients with CD who discontinued any drug class was similar (aminosalicylates, 28.8%; immunosuppressants 35.0%; biologics, 36.3%). However, in UC, aminosalicylates accounted for most treatment discontinuations (65.7%), followed by immunosuppressants (22.1%), whereas biologic therapy accounted for a minority of cases (12.1%). The main reason for discontinuation of immunosuppressants was safety (CD: 53.6%, UC: 51.6%), whereas poor effectiveness ranked top among biologic-treated patients (CD: 58.6%, UC: 58.8%). Overall, 35.7% of IBD patients ever prescribed a biologic (n=46/129), discontinued treatment during a mean (IQR) cumulative treatment duration of 22.1 months (10.9, 35.4) (CD: 30.0%, n=24/80; UC: 28.6%, n=14/49). Detailed information on treatment discontinuation is summarized in Table 4.

DiscussionThis is the first multicenter nationwide study to assess sociodemographic, clinical characteristics, and treatment patterns of adult patients with moderate to severe IBD in Argentina. The study included data from seven IBD referral centers, from the private and public sectors.

Female gender was predominant in both pathologies, in line with previous reports.5,6 Overall, less than 10% of the patients presented with a family history of IBD, and this was more frequent in CD compared to UC (11.8% vs. 5.5%). Similarly, active smokers were more prevalent in CD vs. UC (12.8% vs. 5.5%). In line with Balderramo et al., the frequency of EIMs was higher in CD compared to UC (30.7% vs. 24.1%), whereas a similar proportion of patients with CD or UC presented with other comorbidities.6

Active disease at enrollment was observed in 9.3% of patients with CD and 7.7% of patients with UC. This proportion was lower than that observed in the RISE Brazil study, in which 17.4% of patients with CD and 25.2% of patients with UC were classified as presenting active disease based on the same clinical scores and cut-off values.8 These findings are consistent with the apparently less severe IBD phenotype observed in the patient population in this study. In the Brazilian cohort, more IBD patients had undergone previous IBD-related surgery and had a longer disease duration; in addition, over 82% of CD patients had ileal or ileocolonic disease involvement, whereas stricturing and/or penetrating disease was present in 76% of patients. Importantly, endoscopic outcomes were not assessed in this present study; thus, it is unknown whether patients presenting with clinical remission achieved mucosal healing. According to the STRIDE recommendations, clinical remission should not be the sole treatment goal, as mucosal healing and histological remission are associated with better long-term outcomes.2

In line with the findings from Argentinean referral centers,6,9,10 patients with CD mostly presented with colonic disease (51.5%) and nonstricturing/nonpenetrating behavior (48.5%). Colonic disease appears to be more prevalent in southern Latin American countries, like Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay.4,11 This is in contrast with most countries in the region (e.g., Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico), as well as North America and European countries, where ileocolonic disease has been described as the most frequent CD phenotype.4,8,12,13 The reasons for this finding remain to be explored. While the etiology of CD phenotype is known to be multifactorial, involving environmental, genetic, and immunological factors, there is a lack of studies that specifically investigate this aspect within the Latin American population. As observed in most Latin American countries,4 one-third of the patients with CD in this study presented with perianal disease.

In UC, most patients presented with pancolitis (45.5%), followed by left-sided colitis (41.4%), in line with previous reports from referral centers in Argentina.10,14,15 On the contrary, Balderramo et al. showed a predominance of left-sided colitis (46%), with pancolitis being the least prevalent UC extension (21.6%).6 Regional variations in disease presentation, and the inclusion of data from non-referral centers could explain these differences, as observed in other studies.12,13

Regarding treatment patterns, 73.2% of patients with CD received biologic therapy at enrollment and almost 80% of these patients had been prescribed at least one biologic in the previous 3 years. As reported previously,16 biologics penetration in UC was lower compared to CD; only one-third of the patients were prescribed biologics during the retrospective period. Nevertheless, their use was more common than in other countries in the region, probably due to better access to care.4,16 Studies by Lasa et al. and Balderramo et al. reported a much lower proportion of biologic therapy use in patients with IBD in Argentina: 33.3% (CD) and 24.8% (UC), and 36.4% (CD) and 9.1% (UC), respectively.5,6 However, these studies included patients with IBD irrespective of previous diagnosis of moderate to severe disease. Our findings are in line with those of the RISE Brazil study, in which 71.6% of patients with CD and 28.7% of patients with UC received biologic therapy.8,13 A similarly higher use of biologic therapy (CD: 66.8%, UC: 36.8%) was reported in Caribbean countries (Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Dominican Republic), likely associated with a more aggressive disease behavior (penetrating CD behavior, extensive UC, EIMs).17

Although anti-TNFs have long been a mainstay in IBD management, a considerable proportion of patients do not respond, or lose response to, anti-TNF therapy over time.18–20 In our study, among patients who received a biologic drug, 35.7% discontinued treatment and 17.1% required more than one biologic during the retrospective period. Nevertheless, the requirement for multiple lines of biological therapy is probably higher given that most patients (61%) were diagnosed with moderate to severe IBD before data retrieval. At the time this study was conducted, apart from conventional therapy, only anti-TNFs were widely available for IBD management. In Argentina, vedolizumab was approved a few months before the initiation of the study (2018), whereas ustekinumab received regulatory approval during 2019 and 2020 for CD and UC, respectively; tofacitinib and upadacitinib became available for UC in 2020 and 2023, respectively. Thus, most of the advanced therapies prescribed in this study corresponded to anti-TNF therapy, except for five patients receiving vedolizumab. These results are in line with the LATAM EXPLORE study, in which almost half of anti-TNF-treated patients experienced a suboptimal response to their first-line anti-TNF.21 The rates of discontinuation of anti-TNFs among bio-naïve IBD patients worldwide vary between 25%-65% within 6–36 months of treatment.22–24 Increased adoption of newer therapies with different mechanisms of action (e.g., anti-integrin, anti-interleukin, Janus kinase inhibitors and sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor modulator), and the proper sequencing of advanced therapies within the treatment algorithm, may result in improved treatment outcomes.25–30

At enrollment, monotherapy with biologics was frequent in CD (27.7%), but not in UC, indicating the broad use of conventional therapy in UC (high level of utilization of aminosalicylates and immunosuppressants). Indeed, this study showed that almost all patients with UC (97.9%) received aminosalicylates during the 3-year retrospective period compared with 62.4% of patients with CD. Although aminosalicylates have been used widely for CD globally, the evidence for their effectiveness as maintenance therapy is limited, and clinical guidelines currently warn about their lack of effectiveness.

Overall, the utilization rate of immunosuppressants during the retrospective period was between 45.5% and 58.6%. Upon enrollment, approximately 40% of the patients on a biologic drug were receiving concomitant immunosuppressants, irrespective of the IBD type. This trend was predominant in patients treated with infliximab and, to a lesser extent, in patients treated with adalimumab (mainly in those previously exposed to infliximab combination therapy). Importantly, therapeutic drug monitoring is unavailable in Argentina; thus, combination therapy appears to be more frequent than reported in the United States and Europe, where the determination of anti-drug antibodies and drug levels objectively guides therapeutic decisions.

According to multiple treatment guidelines, corticosteroids are recommended only for the induction of remission. At enrollment, only 15% of patients with IBD received corticosteroids, which is in line with the prevalence of patients with active disease at study entry. However, during the retrospective period, the requirement for corticosteroids was registered in 63.8% of the overall patient population, which is expected in a cohort of patients with a previous diagnosis of moderately to severely active disease and a steroid-dependent/refractory behavior in a considerable proportion (CD: 43.5%, UC: 57.1%). Of note, inadequate response to or, dependency on steroids, lead to the use of biological therapy; thus, it is reasonable to observe high use of biologics in this cohort of patients with IBD.

Interestingly, despite the higher use and longer cumulative treatment duration with biologics in patients with CD compared with UC, healthcare resource utilization (surgeries and hospitalizations) remained higher in patients with CD during the retrospective period. This might indicate that although, there is a high rate of use of advanced therapies in CD, this might be a reactive indication in cases presenting with complications or aggressive disease courses. Nevertheless, overall disease duration since IBD diagnosis and disease duration since moderate to severe disease diagnosis was significantly longer in patients with CD, at least partly explaining the higher use of healthcare resources in this patient population.

Considering the increasing incidence and prevalence of IBD in newly industrialized countries, such as Argentina, it is relevant to understand the therapeutic strategies used in real-world clinical practice to best adjust disease management according to the current international consensus.4 The results of this study can contribute to evidence-based decisions regarding the adoption of advanced therapies in IBD.

The limitations of this study include its retrospective nature, where missing information in medical records may have led to an underestimation of pharmacological treatment use, in addition to the lack of endoscopic assessment at study enrolment. Also, because this study included data from IBD referral centers, the results obtained may not represent overall clinical practice across the country; there is a possibility of selection bias toward more complex cases (and with higher need/access to biologic therapy). Nevertheless, RISE AR is the first multicenter study to described sociodemographics, clinical characteristics, and treatment strategies of patients with IBD from seven IBD referral centers distributed across 4 major districts. As such, it provides a comprehensive overview of the real-world clinical practice of IBD management in Argentina.

In conclusion, this study described the real-world treatment strategies amongst patients with moderate to severe IBD in Argentina. In this cohort, the overall prescription patterns of conventional therapy were similar to those reported elsewhere; however, the use of biologic therapy was high, especially among patients with CD. Notably, 1 in 5 patients required more than one biologic therapy during a 3-year retrospective period, highlighting the need for response-predictive biomarkers and novel therapies with novel mechanisms of action to improve treatment outcomes in IBD.

FundingThis work was supported by Takeda Argentina S.A.

Conflict of interestPA Olivera has received travel support from Ferring, AbbVie, and Takeda; lecture fees from Takeda, AbbVie, and Janssen; and consulting fees from AbbVie, Takeda, and Janssen. DC Balderramo has received travel support from Takeda, AbbVie, Janssen, and Ferring and lecture fees from Takeda, AbbVie, and Janssen, and has participated at advisory boards for Takeda. JS Lasa has received travel support from Sanofi Aventis and lecture fees from AbbVie and Sanofi Aventis. I Zubiaurre has received travel support from Takeda and AbbVie and lecture fees from Takeda, AbbVie, Janssen, and Ferring; has participated at advisory boards for Takeda and AbbVie; and is a consultant for Takeda and AbbVie. G Correa has received travel support from Ferring, AbbVie, Janssen, and Takeda; lecture fees from Ferring, Biotoscana, Janssen, and AbbVie; and consulting fees from AbbVie and Janssen. P Lubrano has received travel support from Ferring, AbbVie, and Takeda and lecture fees from Takeda, AbbVie, Biotoscana, and Janssen. O Ruffinengo has received travel support from Takeda, AbbVie, and Janssen; lecture fees from Janssen; financial support for research from Takeda, AbbVie, and Celgene; and consulting fees from Takeda. M Yantorno has received travel support from Ferring, Abbvie, Janssen and Takeda, received lecture fees from Ferring, Biotoscana, Janssen and Abbvie, and received consulting fees from Abbvie and Janssen. A Rausch has received travel support from Ferring, AbbVie, Jannsen, Biotoscana and Takeda and lecture fees from Takeda, AbbVie, and Janssen. G Piñero has received travel support from AbbVie and Janssen; lecture fees from AbbVie; and consulting fees from Janssen. A Bolomo has nothing to declare. C Amigo, J El-Hakeh, DB Leonardi and L Brion are employees of Takeda. A Sambuelli has received travel support from Ferring, AbbVie, and Takeda and lecture fees from Biotoscana, Janssen, AbbVie, and Takeda.

Data availabilityThe datasets, including the redacted study protocol, redacted statistical analysis plan, and individual participants data supporting the results reported in this article, will be made available within three months from initial request to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. The data will be provided after its de-identification, in compliance with applicable privacy laws, data protection and requirements for consent and anonymization.

The authors would like to thank all the site investigators and their research teams for their participation and contribution in the RISE AR study. In addition, the authors would like to thank Patricia Guimaraens for the invaluable contribution during study oversight, and Federico Ussher who has helped provide critical input for the development of the manuscript. Editorial assistance was provided by David P. Figgitt PhD, CMPP™, Content Ed Net, with funding from Takeda Argentina S.A.