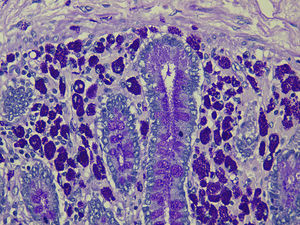

Whipple disease (WD) was described in 1907 as an entity of infectious origin caused by the bacteria Tropheryma whipplei. It consists of macrophages accumulating in the lamina propria with intensely periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive intracellular material.

The disorder is manifested by arthralgia, weight loss, diarrhoea and abdominal pain; there may also be cardiac and central nervous system involvement and, on rare occasions, pulmonary hypertension.

We present the case of a 47-year-old man who had been diagnosed 2 years previously with HLA-B27 undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy, for which he was receiving treatment with anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) agents: adalimumab and, later, etanercept (50mg/week).

The patient had begun to experience abdominal pain and lower limb weakness 4 months earlier. In the latter 2 months he experienced night sweats, fever, anorexia and weight loss of 10kg. In the month prior to admission, he had attended the emergency department on 2 occasions for abdominal pain and diarrhoea; he was admitted when symptoms persisted.

Physical examination showed a slightly distended abdomen with no tender areas, but was otherwise completely unremarkable. Laboratory tests revealed iron deficiency anaemia, with haemoglobin 10.2g/dL, iron 21μg/dL, albumin 2.6g/dL, folate 2.2ng/mL and C-reactive protein 59mg/L; other tests were within reference ranges. A chest X-ray showed no findings of interest.

Results for stool analysis were negative. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed multiple pathologically enlarged retroperitoneal and mesenteric lymph nodes. Colonoscopy was requested but was not done due to the patient's rapid clinical deterioration: on the third day of admission he had several episodes of dyspnoea, tachypnoea and haemodynamic instability. Following a normal electrocardiogram and angio-CT scan that ruled out pulmonary embolism, he was admitted to the intensive care unit.

Several serological studies were performed: atypical pneumonias, hepatotropos virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Legionella antigen and pneumococci in urine, Mantoux test and acid-alcohol resistant bacillus in sputum. Bronchoscopy and bone marrow biopsy results were negative. Tuberculostatics, broad spectrum antibiotics, antiviral agents, antimycotic agents and methylprednisolone boluses were administered empirically. Within a few hours, he presented an episode of asystole. Cardiac ultrasound showed severe pulmonary hypertension (PHT), while chest angio-CT findings were consistent with PHT and mediastinal, retroperitoneal and mesenteric lymphadenopathies (Fig. 1).

Over the following days, the patient's clinical, respiratory and haemodynamic parameters deteriorated. He was treated with high doses of amines and nitric oxide but developed renal failure, anasarca and upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Two endoscopies showed acute gastroduodenal lesions secondary to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. He died 15 days after admission.

The autopsy report was as follows: WD with diffuse involvement of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum and the mesenteric, peripancreatic and perigastric lymph nodes (Fig. 2).

WD generally follows an insidious course. Presentation varies, with several clinical manifestations that imply systemic involvement.1 Arthralgia is an early symptom and usually appears long before gastrointestinal manifestations, making diagnosis difficult.

Immunosuppressive treatment is associated with an increased tendency to develop infections; TNF-α blocking agents, in particular, are associated with a higher risk of infections caused by intracellular pathogens. Various studies postulate that immunosuppressive therapy plays an important role in the exacerbation and rapid progression of digestive symptoms in WD,2–4 although in our case there was insufficient data to determine whether the joint symptoms were due to WD or developed after starting biological therapy.

A French study reported that 5 patients treated with biological agents developed gastrointestinal symptoms consistent with WD. On reviewing each patient retrospectively, they also found that an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in 2 of these patients was reported as normal prior to initiating anti-TNF therapy. The authors concluded that biological treatments caused rapid progression of pre-existing early-stage WD. Although the mean interval between the development of initial symptoms (arthralgia and arthritis) and of intestinal symptoms is 6 years, this period is dramatically shortened in immunocompromised patients.4

Noteworthy in our patient was the associated PHT, given that only 7 cases of this rare symptom have been described in the literature. Most were patients with no previous heart disease. There was no other explanation for the PHT,5–8 which appeared to improve after instigating antibiotic therapy.

Histological analyses suggest that the PHT may be caused by partial obliteration of the lumen of the pulmonary arteries by macrophages and fibrinoid debris,7 and PAS-positive bacteria and macrophages have been identified in the media of the pulmonary arteries and in the adventitia, respectively.9 PHT resolution following antibiotic treatment supports the above hypothesis. The PHT that debuted de novo in our patient contributed to his gradual deterioration. The failure to improve following administration of antibiotics was possibly because symptoms were already very advanced.

We conclude that the interval between arthralgia and WD diagnosis is shortened in immunocompromised patients. The severity of the disease is determined by the duration of biological treatments, regardless of the drug used. WD needs to be considered in patients with long-standing joint symptoms, and should be ruled out by oral endoscopy and small bowel biopsies before biological therapy is commenced.

Please cite this article as: Estévez-Gil M, de Castro-Parga ML, Carballo-Fernandez C, San Martín-Alonso M, Machado-Prieto B, Cid-Gómez LA, et al. Enfermedad de Whipple en un paciente en tratamiento con anti-TNF-α. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:334–335.