Adenosquamous cancer of the pancreas (ASCP) is an aggressive, infrequent subtype of pancreatic cancer that combines a glandular and squamous component and is associated with poor survival.

MethodsMulticenter retrospective observational study carried out at three Spanish hospitals. The study period was: January 2010–August 2020. A descriptive analysis of the data was performed, as well as an analysis of global and disease-free survival using the Kaplan–Meier statistic.

ResultsOf a total of 668 pancreatic cancers treated surgically, twelve were ASCP (1.8%). Patient mean age was 69.2±7.4 years. Male/female ratio was 1:1. The main symptom was jaundice (seven patients). Correct preoperative diagnosis was obtained in only two patients. Nine pancreatoduodenectomies and three distal pancreatosplenectomies were performed. 25% had major complications. Mean tumor size was 48.6±19.4mm. Nine patients received adjuvant chemotherapy. Median survival time was 5.9 months, and median disease-free survival was 4.6 months. 90% of patients presented recurrence. Ten of the twelve patients in the study (83.3%) died, with disease progression being the cause in eight. Of the two surviving patients, one is disease-free and the other has liver metastases.

ConclusionASCP is a very rare pancreatic tumor with aggressive behavior. It is rarely diagnosed preoperatively. The best treatment, if feasible, is surgery followed by the standard chemotherapy regimens for pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

El cáncer adenoescamoso de páncreas (CPAS) es un subtipo de cáncer de páncreas agresivo e infrecuente que combina un componente glandular y escamoso, y presenta baja supervivencia.

MétodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo multicéntrico realizado en tres hospitales españoles. El período de estudio fue: enero 2010 - agosto 2020. Se realizó un análisis descriptivo de los datos, así como un análisis de supervivencia global y libre de enfermedad mediante Kaplan-Meier.

ResultadosDe un total de 668 cánceres de páncreas tratados quirúrgicamente, doce fueron CPAS (1,8%). La edad media de los pacientes fue de 69,2±7,4 años. La proporción hombre /mujer fue de 1: 1. El síntoma principal fue la ictericia (siete pacientes). Se obtuvo un diagnóstico preoperatorio correcto en solo dos pacientes. Se realizaron nueve duodenopancretectomías cefálicas y tres pancreatoesplenectomías distales. El 25% tuvo complicaciones mayores. El tamaño medio del tumor fue de 48,6±19,4mm. Nueve pacientes recibieron quimioterapia adyuvante. La mediana de supervivencia fue de 5,9 meses y la mediana de supervivencia libre de enfermedad fue de 4,6 meses. El 90% de los pacientes presentó recidiva. Diez de los doce pacientes del estudio (83,3%) fallecieron, y la progresión de la enfermedad fue la causa en ocho. De los dos pacientes que sobrevivieron, uno está libre de enfermedad y el otro tiene metástasis hepáticas.

ConclusiónEl CPAS es un tumor pancreático muy raro y de comportamiento agresivo. Rara vez se diagnostica antes de la operación. El mejor tratamiento, si es posible, es la cirugía seguida de los regímenes de quimioterapia estándar para el adenocarcinoma de páncreas.

Adenosquamous cancer of the pancreas (ASCP) is an aggressive, infrequent subtype of pancreatic cancer which combines glandular and squamous component and is associated with poor survival.1–4 There are no studies of the geographical incidence of ASCP, although most publications are based on populations in Asia or from the SEER database in the US.5–9 Only three European series have been published to date.1,3,9

The etiology of ASCP is unknown. Several hypotheses have been published regarding its histogenesis.5 According to the collision theory, two histologically distinct tumors may arise independently in the pancreatic tissue and eventually coalesce. Alternatively, it has been proposed that squamous metaplasia occurs due to obstructive ductal inflammation, or that a pancreatic pluripotential cell differentiates into a squamous or adenocarcinoma.5,8,9 It is not known whether the typical risk factors for ASCP are the same as for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PA).5,9

The diagnosis of ASCP requires the presence of at least 30% of a squamous component in the tumor.2,3,5,6,8,9 Nevertheless, this figure is controversial due to the subjectivity of the measurement and the difficulty of defining the percentage on the basis of a biopsy alone. Some authors suggest that in the presence of squamous cells ASCP should be considered.9 Tumor cell necrosis in ASCP is common, and the growth rate is twice that of PA due to the rapid proliferation of the squamous component.8,9 ASCP immunohistochemistry is positive for CK5/6 and 7 and p63, and negative for CK20, p16, and p53.1,9 It is usually located in the periphery and the adenocarcinoma in the center, with a transition zone in which the glandular structures become squamous. It frequently presents vascular invasion, but only rarely lymph node metastases.

The prognosis of ASCP is poor with survivals of 4–19 months and early relapses probably related to squamous component.1–9

Here, we present a multicenter retrospective series from Spain with data from three hospitals, aiming to determine the epidemiological characteristics of this rare tumor and to present the oncological results obtained.

MethodsMulticenter, retrospective observational study of prospective data from pancreatic cancer databases stored at the Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery Departments of three Spanish hospitals. The study period was between 1 January 2010 and 31 August 2020. The inclusion criterion was any pancreatic tumor operated on with final pathological diagnosis of ASCP, and the exclusion criteria were other histological findings (squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, etc.). The study was carried out in accordance with STROBE guidelines (supplementary Table 1).10

Each participating hospital appointed a local manager to carry out the data recording and to liaise with the overall study coordinator. All data were recorded by local manager at each hospital, and the project coordinator had access to medical data only.

DefinitionsDiagnosis was based mainly on CT scan, MRI and EUS plus biopsy. The surgical techniques included pancreatoduodenectomy and distal pancreatosplenectomy. For the diagnosis of ASCP, the presence of a squamous component occupying at least 30% in the tumor tissue was established as mandatory. Complications were assessed at 90 days using the Clavien-Dindo (CD) classification, and those defined as Clavien-Dindo grade IIIa or higher were considered major.11 For the recording of complications, the medical and nursing notes of the electronic histories of each patient were consulted. For the complications specifically associated with pancreatic surgery, the definitions of the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) of delayed gastric emptying,12 post-pancreatic hemorrhage13 and pancreatic fistula14 were used. The resection margins of the surgical specimen were categorized according to the definitions of the Royal College of Pathologists: R0 (margin to the tumor≥1mm), R1 (margin to the tumor<1mm) and R2 (macroscopically positive margin).15 Tumors were staged according to the TNM classification 8 Ed.,16 but arterial involvement is considered T4 only in ASCP. Chemotherapy was given in a variety of regimens if the patient was >T2 or had positive nodes and was fit to receive this treatment after surgery. The follow-up regimen comprised an outpatient clinical visit every three months during the first two years including tumor marker assessment and CT/MRI. No patient received neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

VariablesThe following variables were studied: age, gender, main clinical symptom; serology tests: hemoglobin (g/dl), bilirubin (mg/dl), ALT (U/l), AST (U/l), calcium (mg/dl), CEA (ng/ml) and CA19-9 (U/ml); radiological/endoscopic tests performed (CT/MRI/EUS), including lesion size and location, preoperative biopsy, preoperative diagnosis of ASCP; surgical procedure performed and morbidity/mortality.11–14 The histological data retrieved were TNM tumor size and lymph nodes harvested, grade, and R status. Chemotherapy protocol, time of relapse, disease-free and overall survival from date of diagnosis, cause of death and postoperative follow-up (months) were also recorded.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were tested for Gaussian distribution by the Shapiro–Wilk test; those with normal distribution were presented as means and standard deviations (SD) and non-normal variables were reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Kaplan Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed to model all-cause mortality and relapse-free survival from the day of surgery. Data were analyzed using R version 3.1.3 (http://www.r-project.org) and the appropriate packages.

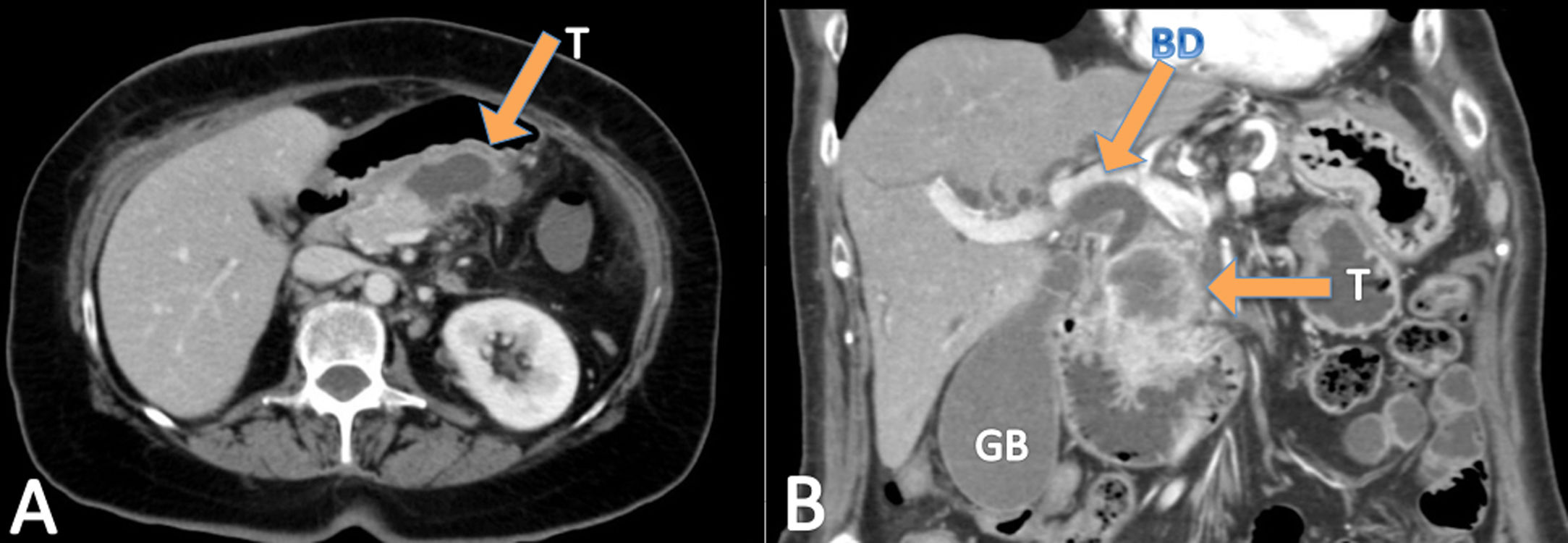

ResultsDuring the study period, the three units operated on a total of 668 pancreatic cancers, of which twelve were ASCP (1.8%). Mean age of patients with ASCP was 69.2±7.4 years, and the male/female ratio was 1:1 (six men and six women). The main symptom was jaundice (seven patients), abdominal pain (three), cholangitis (one), and vomiting (one). All 12 patients underwent abdominal CT (Fig. 1), nine EUS, and seven abdominal MRI. Nine tumors were located in the head of the pancreas and three in the body/tail. Mean preoperative tumor size was 39±19mm. Preoperative biopsies were performed in nine patients (75%), 8 by EUS and one biopsy of ampullar lesion, but only two identified ASCP. Therefore, in ten patients (three not biopsied and seven biopsied) (83.3%), the preoperative diagnosis was adenocarcinoma of the pancreas (PA). The mean laboratory test values were: hemoglobin: 11.5g/dl (1.70) (normal values: 11.5–16g/dl); total bilirubin: 2.89mg/dl [0.32;9.47] (0–1.2mg/dl); AST: 87.0U/l [20.5;180] (0–32 UI/l); ALT: 81.5U/l [26.5;250] (0–33 UI/l); CEA: 7.88ng/dl (7.25) (0–5ng/dl); CA 19–9: 47.5 UI/l [38.4;67.6] (0–37 UI/l), and serum calcium: 8.67 (1.05) mg/dl (8.5–10.5mg/dl) (Table 1).

Epidemiological and diagnostic tests.

| Case | Age | Gender | Main clinical symptom | CT | MRI | Size (mm) | USE | Preop. biopsy | Preop. ASCP biopsy | TB (mg/dl) | AST (U/l) | ALT (U/l) | CEA (ng/ml) | CA 19.9(U/ml) | HB (g/dl) | Ca (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 73 | Male | Abdominal pain | YES | NO | 50 | NO | NO | NO | 0.9 | 19 | 30 | No | No | 14.1 | 8 |

| 2 | 67 | Female | Jaundice | YES | YES | 26 | YES | YES | NO | 0.73 | 89 | 115 | No | No | 9.3 | 7.3 |

| 3 | 63 | Male | Acute Cholangitis | YES | YES | 45 | YES | YES | NO | 4.88 | 141 | 197 | 0.8 | 67.1 | 13 | 9.4 |

| 4 | 60 | Female | Jaundice | YES | NO | 21 | YES | YES | NO | 0.36 | 21 | 16 | 9.2 | 38.4 | 12.4 | 9 |

| 5 | 73 | Female | Jaundice | YES | NO | 16 | YES | YES | YES | 13.72 | 85 | 48 | 3.2 | 46.8 | 13.2 | 9.7 |

| 6 | 64 | Female | Abdominal pain | YES | NO | 31 | YES | YES | YES | 0.2 | 52 | 31 | 7.8 | 286 | 8.4 | 9 |

| 7 | 79 | Female | Jaundice | YES | NO | 27 | YES | YES | NO | 8.06 | 230 | 291 | 21.3 | 28 | 11.7 | 9.5 |

| 8 | 73 | Female | Abdominal pain | YES | YES | 85 | NO | NO | NO | 0.2 | 11 | 8 | No | No | 10.9 | 7.5 |

| 9 | 71 | Male | Jaundice | YES | YES | 34 | YES | YES | NO | 7.7 | 209 | 377 | no | 67.6 | 12.4 | 9.3 |

| 10 | 55 | Male | Jaundice | YES | NO | 40 | YES | NO | NO | 17.2 | 170 | 236 | No | 3.6 | 9.9 | 7 |

| 11 | 78 | Male | Jaundice | YES | YES | Ampuloma (no mesurable) | NO | YES | NO | 15 | 432 | 615 | No | 47.46 | 12.2 | 10.2 |

| 12 | 74 | Male | Vomiting | YES | NO | 50 | YES | YES | NO | 0.2 | 12 | 6 | 4.95 | 671 | 11 | 8.1 |

Preop: preoperative. TB: total bilirubin. Hb: hemoglobin. Ca.: calcium.

As regards surgical technique, nine pancreatoduodenectomies were performed (in one case associated with right hemicolectomy and in another with wedge resection of one small unique liver metastasis), and three distal pancreatosplenectomies (in one patient combined with left nephrectomy and partial gastrectomy). The resection of neighboring organs was always due to local tumor growth. Fifty-eight per cent of patients had minor complications (three grade I and four grade II), and 25% major complications (two IIIA and one V due to multiorgan failure). Regarding the complications of pancreatic surgery, two patients had type B pancreatic fistula of ISGPS classification, three had biochemical fistula (previous known as A) and seven did not have postoperative fistula. One patient presented delayed gastric emptying type A of ISGPS and another postoperative hemorrhage type A of ISGPS; two intra-abdominal abscesses were detected and treated by percutaneous drainage (Table 2).

Surgery and pathology.

| Case | Surgical technique | Clavien | Pancreas fistula BQ/B/C | DGE | Hemhorrrage a/b/c | Biliary fistula | IA abscess | Size (mm) | Lymph nodes (+/total) | Grade | Necrosis | IHQ | R | TNM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Distal pancreatectomy+splenectomy | II | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | 60 | 6/11 | G3 | NO | ND | R1 | pT3N1M0 |

| 2 | Pancreatoduodenectomy | V | BQ | NO | A | NO | NO | 32 | 1/25 | G3 | NO | ND | R0 | pT2N1M0 |

| 3 | Pancreatoduodenectomy | II | BQ | NO | NO | NO | NO | 70 | 2/14 | G3 | NO | ND | R1 | pT3N1M0 |

| 4 | Pancreatoduodenectomy | II | NO | NO | NO | NO | SI | 38 | 2/19 | G3 | NO | ND | R0 | pT2N1M0 |

| 5 | Pancreatoduodenectomy | I | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | 20 | 1/17 | G3 | NO | CK7, p40, p63 y MUC1 | R0 | pT2N1M0 |

| 6 | Distal pancreatectomy plus splenectomy+nephrectomy+parcial gastrectomy | IIIA | B | NO | NO | NO | NO | 55 | 0/14 | ND | ND | ND | R0 | pT3N0M0 |

| 7 | Pancreatoduodenectomy | O | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | 53 | 0/12 | ND | ND | ND | R0 | pT3N0M0 |

| 8 | Distal pancreatectomy+splenectomy | I | BQ | NO | NO | NO | NO | 90 | 0/18 | G3 | ND | ND | R1 | pT3N0M0 |

| 9 | Pancreatoduodenectomy+liver wedge resection | IIIA | B | A | NO | NO | SI | 45 | 1/6 | G2 | ND | ND | R0 | pT2N1M1 |

| 10 | Pancreatoduodenectomy | O | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | 35 | 1/13 | G3 | ND | ND | R2 | pT2N1M0 |

| 11 | Pancreatoduodenectomy | II | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | 30 | 1/41 | G2 | ND | ND | R0 | pT2N1M0 |

| 12 | Pancreatoduodenectomy+right hemicolectomy | I | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | 55 | 1/15 | G3 | ND | IMS - | R0 | pT3N1M0 |

BQ: biochemical. DGE: delayed gastric emptying. IA: intra-abdominal abscess. ND: no disposable. IHQ: immunohistochemistry study.

The mean definitive tumor size recorded in the specimen was 48.6±19.4mm. The degree of differentiation was G2 (two patients), G3 (eight) and undetermined in two. No necrosis was observed in five patients (41.7%). The R0 rate was 66.7%. The TNM distribution was T2N1M0 (five patients), T2N1M1 (one, due to a single resected liver metastasis), T3N0M0 (three); T3N1M0 (three).

Nine patients received adjuvant chemotherapy (9/12.75%), two were unfit for chemoteraphy and one patient died in postoperative period. Eight received regimens based on gemcitabine: two alone, four in combination with capecitabine, one with abraxane and one with oxaliplatin, and one patient was administered 5-fluorouracil plus folinic acid. One patient received radiation therapy. No patient received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Table 2).

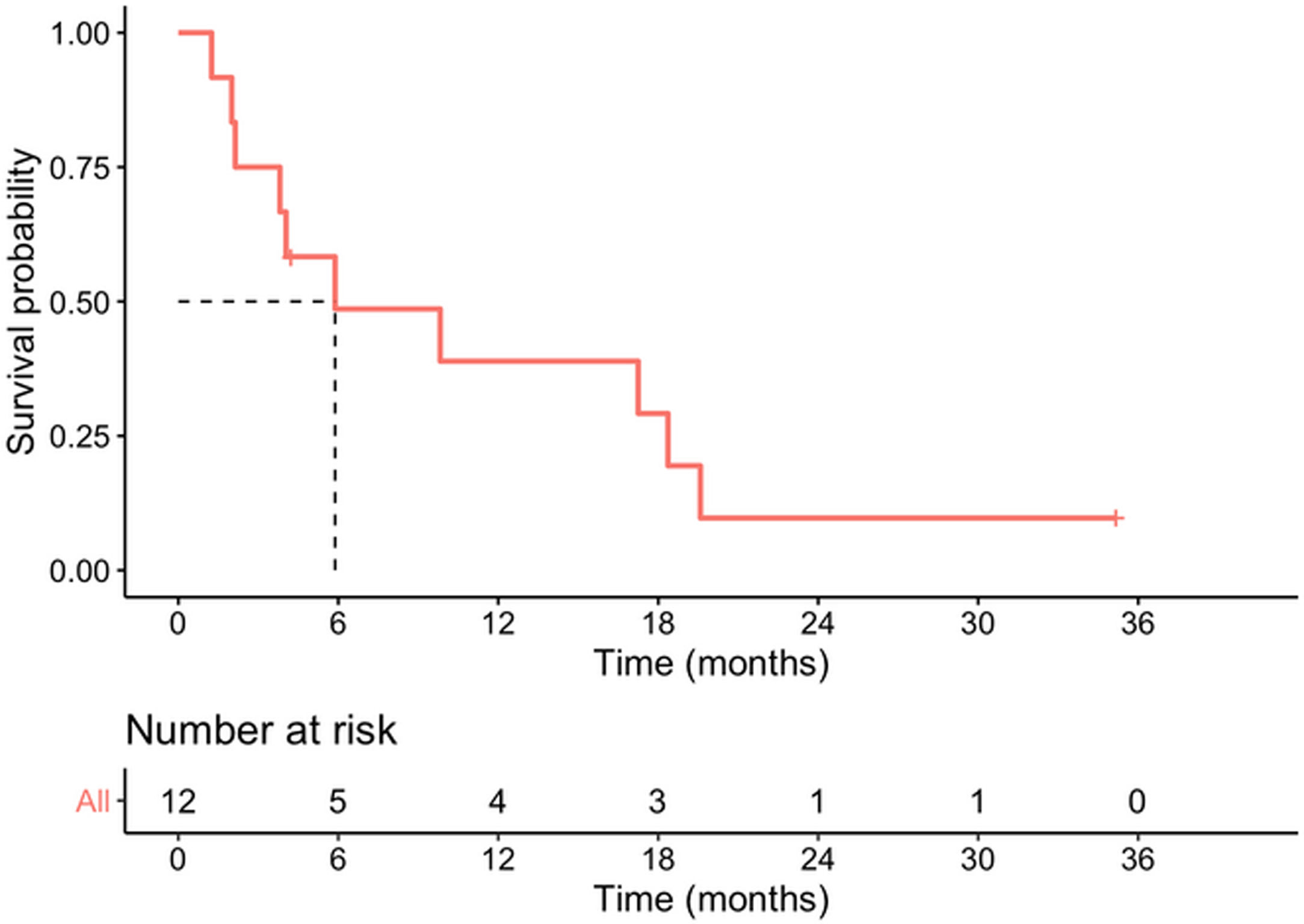

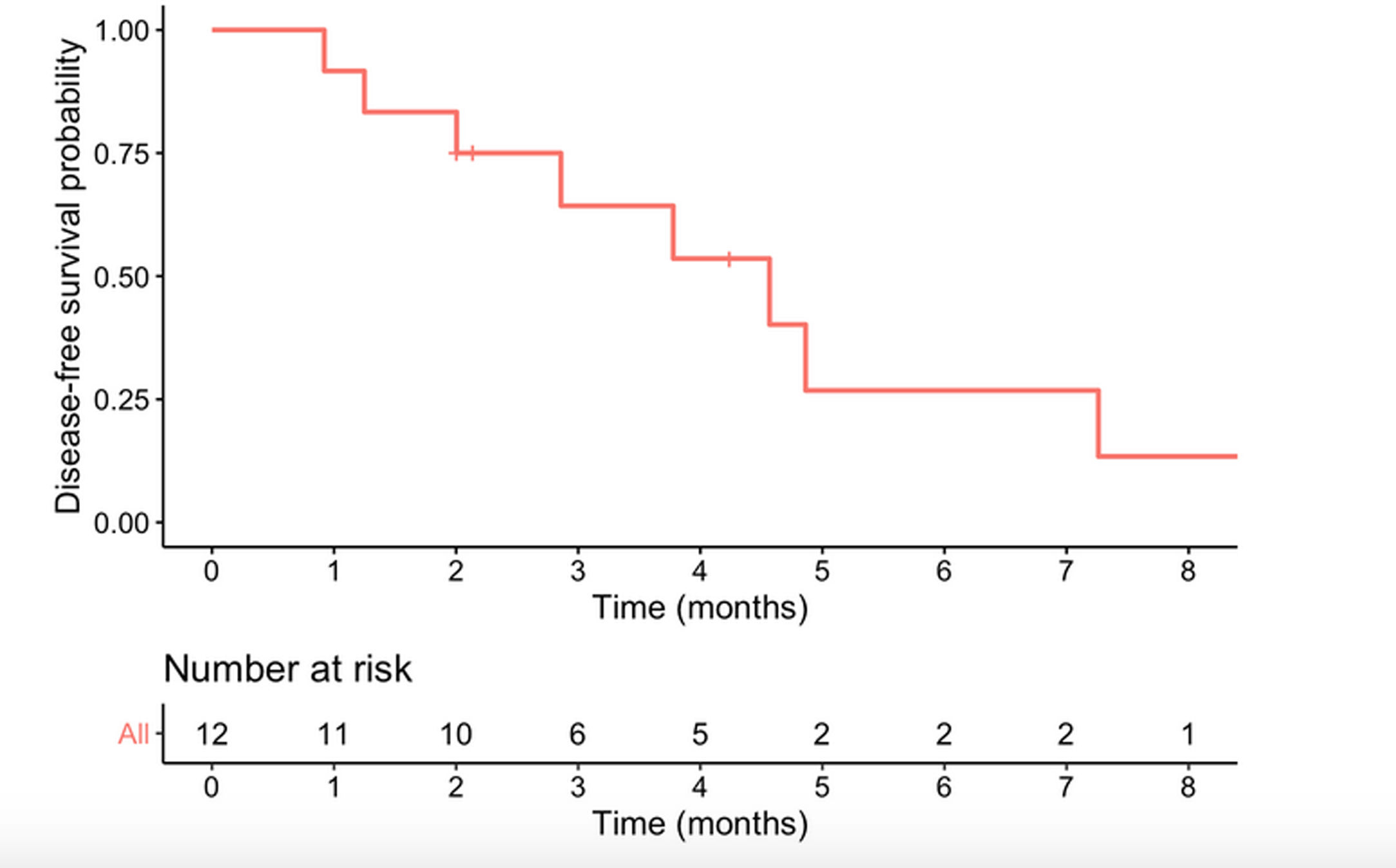

Median survival time from date of diagnosis was 5.9 months, and median disease-free survival was 4.6 months. The 1-year survival probability was 0.38 (95% CI: 0.19–0.81). One patient died in the immediate postoperative period due to multiorgan failure (8.3%), and another four months after surgery due to upper gastrointestinal bleeding, with no evidence of recurrence. Of the remaining 10 patients, nine (90%) presented recurrence: five liver metastases, one liver metastases and locoregional recurrence, one liver metastases and peritoneal carcinomatosis, one peritoneal carcinomatosis and one locoregional recurrence. In total, 10 of the 12 patients in the study (83.3%) died, with disease progression being the cause in eight. Of the two surviving patients, one is disease-free but only has a follow-up of 4.2 months and the other has liver metastases diagnosed at 29 months with overall survival of 35 months (Table 3, Figs. 2 and 3).

Oncological results.

| Case | Adjuvant therapy | Relapse | Type of relapse | Exitus | Free disease survival months | Overall survival months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gemcitabine-Capecitabine | Yes | Liver metastasis | Disease progression | 0.9 | 4.1 |

| 2 | No | No | – | Postoperative urological sepsis | – | 2.2 |

| 3 | No | Yes | Peritoneal carcinomatosis | Disease progression | 2.0 | 3.9 |

| 4 | Gemcitabine | Yes | Liver metastasis | No | 2.9 | 36.2 |

| 5 | Gemcitabine | No | – | No | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| 6 | Gemcitabien-oxaliplatin | Yes | Local relapse | Disease progression | 8.6 | 18.7 |

| 7 | No | Yes | Liver+carcinomatosis | Disease progression | 7.4 | 10.0 |

| 8 | Gemcitabine | No | – | Upper digestive bleeding | 4.1 | 4.1 |

| 9 | Tegafur+folinic acid | Yes | Liver metastasis | Hypercalcemia and fungal infection | 4.6 | 6 |

| 10 | Gemcitabine-Abraxane | Yes | Liver metastasis+local relapse | Disease progression | 1.3 | 4.4 |

| 11 | Gemcitabine | Yes | Liver metastasis | Disease progression | 3.8 | 7.7 |

| 12 | Gemcitabine-Capecitabine+RT | Yes | Liver metastasis | Disease progression | 4.9 | 17.5 |

RT: radiotherapy.

ASCP is an extremely rare condition, accounting for only 0.38–4% of all pancreatic tumors.3 It was first described in 1907 by Herheimer.1,2,5,8,9,17–19 It has received multiple names, including adenoacanthoma, adenocarcinoma with squamous metaplasia, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma.9,17,18

The typical ASCP patient is male (male/female ratio 2:1), in the sixth decade of life.3–5 There is no consensus among the series regarding the most frequent location (either the head of the pancreas or the tail).1,2,3,5,7–9,17 In our series, the male/female ratio was 1:1, mean age was 69 years and the tumor site was three times more likely to be the head of the pancreas than the body/tail.

Clinically, patients with ASCP present symptoms similar to those of PA: abdominal and/or back pain, weight loss, nausea and or vomiting, anorexia, and jaundice.1,5,17 In our study jaundice was the most frequently recorded main symptom, caused by the predominance of pancreatic head lesions. As previously reported elsewhere, laboratory tests in our sample presented elevated liver parameters, anemia, and elevated tumor markers.1,2,5,7,9–11,18 A few cases of malignant hypercalcemia associated with ASCP have been described.5,9 None of our patients presented this condition pre-operatively, but one case was recorded later (a patient with tumor recurrence).

The radiological features of ASCP based in literature data are: these tumors tend to be ill-defined, show central necrosis in 75%; they are solid in 25%, they present enhancement, vascular and neural entrapment and exophytic growth, and duodenal invasion in up to 30% of ASCPs.5,9,17,19 In PET-CT, ASCP has more intense FDG uptake than conventional PA both on early and delayed phase. Retention index value of PASC is positive.20 The usual preoperative radiological and histological diagnosis is PA,9 and in our series more than 80% of the patients received this diagnosis. The diagnosis of ASCP is generally made after the histological study of the surgical specimen; in our series, it was diagnosed after the preoperative biopsy in only two cases.

The recommended treatment for ASCP, when feasible, is surgical resection in order to improve survival.1,4,5,9,18 It is not clarified whether neoadjuvant therapy might improve oncology outcomes.4 As there are no specific neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment regimens for ASCP, the same ones are used as for PA.1 It has been suggested that platinum-based therapies may improve survival.5,9,17 Older age and comorbidities were associated with a reduced likehood of receiving adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.4 It is not clear whether radiotherapy can improve oncological outcomes in ASCP.9 Survival rates in ASCP are 21.2–50.7% at one year, 10.8–29% at two years, and 8–14% at three years, with a median survival that ranges between 5 and 15 months according to series.1,7–9,18,21 Hue et al got a better survival in the surgery plus chemotherapy group4. The rates are always lower than those reported for PA.1,7–9,18,19 Our results are similar to those published in the literature, which record very short survival periods.

Comparative studies of ASCP and PA show that ASCP are frequently poorly differentiated, larger, with higher vascular and perineural invasion, and greater lymph node involvement (though not in all series), which explains their worse prognosis.1,7,8 But, Kaiser et al showed that after matching for the unevenly distributed prognostic factors survival after resection of ASCP and PA was comparable3.

Recurrence is normally early, affecting the liver, lung and retroperitoneum, and malignant ascites is frequent.1,8,9 In our series, recurrence occurred early and was localized, either in the liver or locally. Factors associated with poor survival in ASCP series are tumor size, lymph node involvement, presence of metastases, high CA19-9 levels, advanced age, location in the distal pancreas, positive surgical margin, the impossibility of surgical resection and the non-administration of adjuvant treatment.1,3,9

The limitations of the study are its retrospective nature, the small number of cases, the analysis only of surgical cases may imply a selection bias, as it is a multicenter study, the radiological techniques may differ between centers, which does not allow establishing more definitive data on the radiological characteristics of these tumors and finally the immunohistochemical study was only performed in a single patient, so it cannot be ruled out that the presence of a squamous component may be secondary to invasion of other organs (bile duct, duodenum, etc.). The strengths are that very few studies have been conducted in Europe on this type of tumor.

ConclusionsASCP is a very rare, aggressive pancreatic tumor. It is rarely diagnosed preoperatively unless squamous cells are observed in a preoperative biopsy. Central necrosis is the only radiological finding that can suggest its presence. The best treatment, if feasible, is surgery followed by the standard chemotherapy regimens for PA, as there are no conclusive studies indicating that other alternatives would obtain better results. A European multicenter study could provide us with more complete information on this type of tumors in western patients.

Authors’ contributionsConception and design of the work: JM Ramia.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors.

Drafting the work or revising: JM Ramia, M Serradilla, Gerardo Blanco.

Final approval of the version to be published: All authors.

Statement of ethicsThe study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital General Universitario de Alicante Ethics Committee decided that patients’ informed consent was not required since the study was retrospective and observational and entailed no risk and the majority of patients were dead.

Data availability statementAll data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article [and/or] its supplementary material files. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Funding sourcesThis manuscript did not receive any funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.