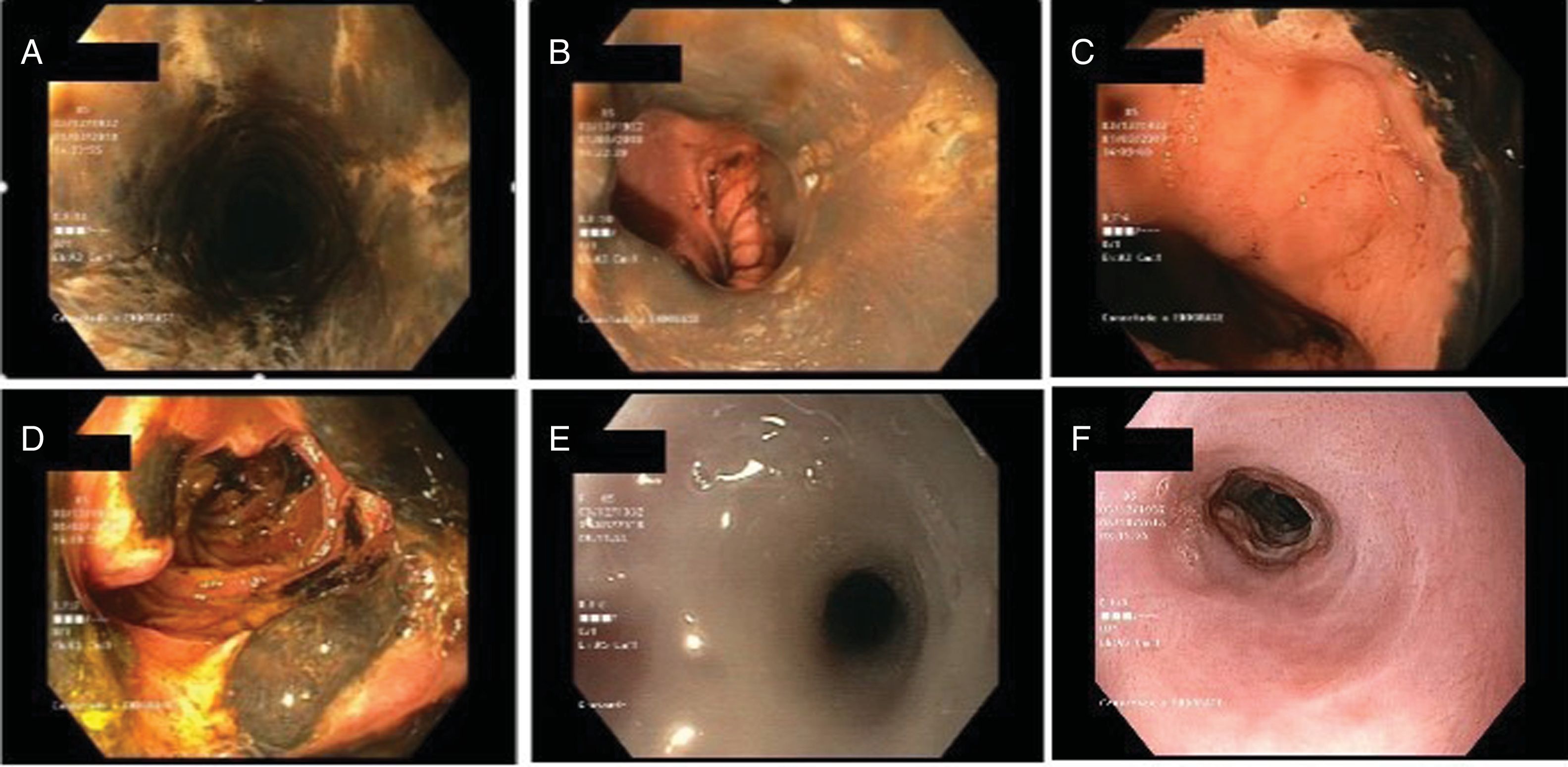

We present the case of an 85-year-old female patient with a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia and pulmonary embolism. She had been experiencing epigastric pain for the past 3 days associated with nausea and vomiting. Laboratory testing found high acute-phase reactants. A plain X-ray and an abdominal CT scan were also performed and showed gastric dilatation and signs suggestive of chronic pancreatitis. It was decided to extend the study by performing a gastroscopy. This revealed an oesophageal surface with blackish discolouration from the proximal oesophagus (Fig. 1A) that did not detach with lavage, suggestive of a necrotic process, associated with longitudinal ulcerations and an abrupt change in the oesophageal–gastric transition (Fig. 1B and C), with no evidence of lesions in the stomach. Multiple ulcers alternating with areas of necrosis were also present in the second duodenal segment (Fig. 1D). Biopsies taken confirmed necrotic ischaemic changes in the duodenal mucosa.

Endoscopic findings. (A) Mucosa of the medial oesophagus with blackish discolouration and longitudinal ulcerations. (B and C) Abrupt stop at the gastro-oesophageal junction. (D) Necrosis of the second duodenal segment. (E) Obstructive oesophageal stenosis shown on follow-up gastroscopy. (F) Course of oesophageal stenosis following several sessions of dilatation.

Given the endoscopic findings, another CT scan was performed, this time a thoraco-abdominal CT scan, which ruled out complications. Treatment was started with total parenteral nutrition and intravenous omeprazole as well as empirical antifungal and antibiotic coverage with meropenem and fluconazole. The patient's subsequent clinical course was satisfactory; therefore, following conservative management for 15 days, another gastroscopy was performed. It showed an oesophageal mucosa with a whitish appearance, covered in fibrin, with a decrease in its calibre towards the cardia, which exhibited obstructive stenosis (Fig. 1E). Several sessions of endoscopic dilatation were performed successfully (Fig. 1F).

Acute oesophageal necrosis is an uncommon entity reported for the first time in 1990 by Goldenberg et al.1 It primarily affects males in their fifties,2 and its prevalence and incidence are low, though its exact incidence and prevalence cannot be known, as it is an under-diagnosed condition.3 Its aetiology is multifactorial, and primarily secondary to ischaemic damage in patients with cardiovascular risk factors and in a context of haemodynamic compromise or low output, including sepsis, heart failure, acute haemorrhage and systemic inflammatory response. Circulation from branches of the coeliac trunk indicates that there may be concomitant lesions in the distal oesophagus and duodenum. Other factors that influence the development of lesions are abnormalities in oesophageal defensive mechanisms and massive passage of gastric contents towards the oesophagus.3 In the case reported, a potential flare-up of chronic pancreatitis in a patient of advanced age with cardiovascular risk factors is put forward as a possible trigger of oesophageal and duodenal lesions.

In up to 90% of reported cases the initial sign is upper gastrointestinal bleeding,3 though other symptoms such as abdominal pain and vomiting may appear or the patient may be asymptomatic. The condition is diagnosed by gastroscopy. It is not strictly necessary to perform biopsies, as the lesions are very distinctive and include a blackish oesophageal mucosa, which essentially affects the distal third (the least vascularised area), with an abrupt stop at the gastro-oesophageal junction.2 Concomitant duodenal involvement in the form of necrosis, ulcers and/or inflammatory changes may appear in up to 50% of cases.5 It is important to perform a differential diagnosis with other conditions, especially if there is isolated involvement of the medial or proximal oesophagus; it is necessary to rule out infectious disease, melanoma, acanthosis nigricans and ingestion of caustic substances.4 In the case presented, the patient denied having ingested caustic substances, and viral serology was performed and came back negative.

In general, management is conservative and includes management of underlying disease and supportive measures such as fluid therapy, total parenteral nutrition, treatment with proton-pump inhibitors at high doses and sucralfate.5 The use of empirical antibiotic treatment is controversial and is recommended if there is evidence of bacterial infection or suspected perforation. In this case, conservative management was pursued after complications were ruled out.

Overall mortality may be as high as 32%2 and is primarily associated with comorbidities as well as the seriousness of the underlying disease. The most feared complication is perforation. This appears in less than 7% of cases and usually requires a surgical approach. Treatment with an oesophageal stent may be considered in select cases.4 The most common complications include the development of stenosis (in 25% of cases)5; this can generally be managed with endoscopic dilatation.

Please cite this article as: Laredo V, Navarro M, Alfaro E, Cañamares P, Abad D, Hijos G, et al. Esófago negro (necrosis aguda esofágica). Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;43:201–202.